This is the second installment of a two-part interview with Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb about her book Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror, 1817-2020 (out now with University of Chicago Press). For the first installment, see here.

Anne Schult: Reading Epidemic Empire, I was struck by how the “epidemic imaginary”—and its associated metaphors of contagion, spread, growth, infection, outbreak, inoculation, and immunity—knits together political organization and science in profound ways. One of these epidemic metaphors also plays a big role in Ed Cohen’s recent book A Body Worth Defending. Though he equally identifies the nineteenth century as a starting point for the conceptual merger between health and politics, Cohen makes an argument for the opposite direction of transmission: he suggests that in the case of immunity, it was long-standing perceptions about human social organization that entered into and transformed the biomedical lexicon, as immunity had existed as a legal concept since ancient Rome. Rather than seeing Cohen’s study as a competing argument, though, I would like to ask: if taken together, what do these terminological vacillations tell us about the historical permissiveness of what we now think of as discrete disciplines, and about the broader stakes of modern biopolitics?

Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb: At this late stage in the process of making this book, I think less and less about directionality and more and more in terms of a constant mutual reinforcement. I really hope that what I’ve written doesn’t suggest that language or figure flows in one way: from science into politics. I will say I felt immense pressure as I wrote the book to “pick” one of these arguments, to declare “it started in this field, and moved into the other!” I’m not sure why there is this pressure to pick—I wonder if it has something to do with the inherited polemicism of certain European and North American Marxist criticism. I don’t see this as much in the South Asian, Caribbean, and Black American archive of Marxist theory.

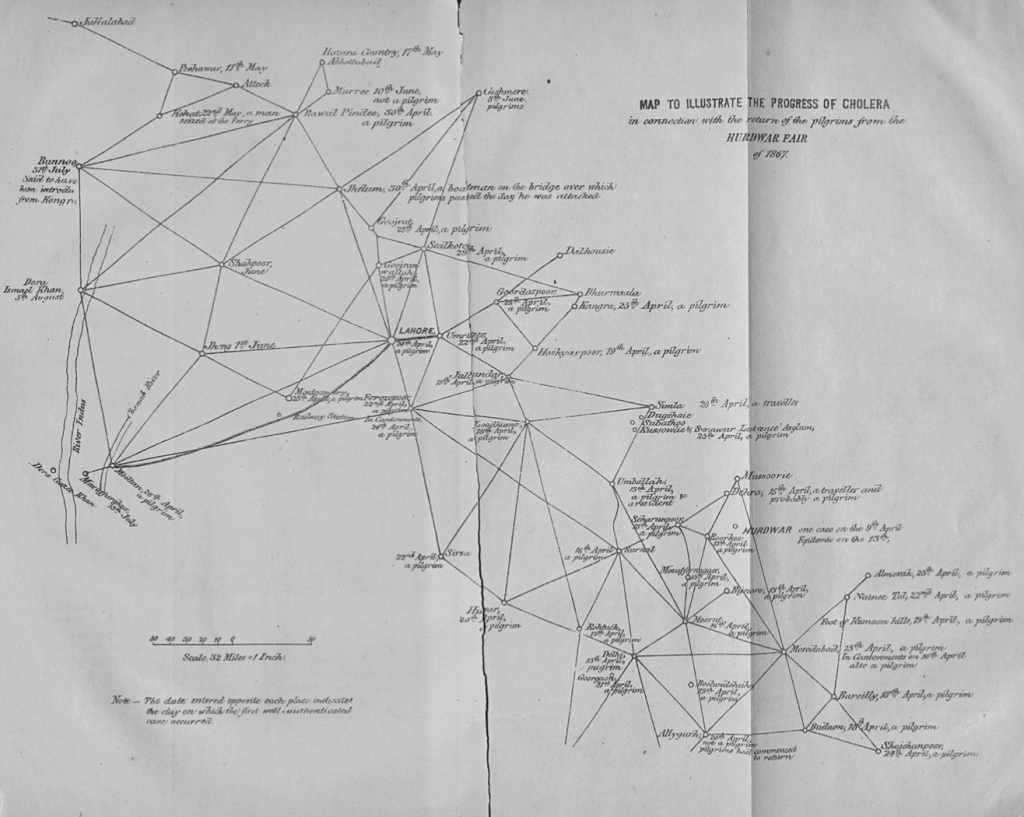

In any case, what seems clear to me from the documents I worked with is that there’s a difficult and always mobile permeation between the two realms, a vacillation, as you say—let’s call them science and politics for the sake of simplicity. So you see invocations of war, siege, battle, and defense in the early writing of the Royal Epidemiological Society (late 1850s) just as you see an insistence on contagion, infection, and pathology in the writings of British historians of the Mutiny. As you say in the first part of our conversation, it was crucial to me to study the coinciding of cholera and the anti-colonial uprisings in India. It helped me understand how these discourses bolstered each other and changed the parameters of what we understand to be “disease” and what we understand to be “insurrection.” And in this instance, although the language functions metaphorically, they were talking about very concrete, very material bodily experiences.

I want to be sure to answer your question, but I am also going to swerve because the events in the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 have brought me back to some of my earliest questions about epidemics and insurgency. Today, we are not talking about a figural overlap. As in the late 1850s in India, we are talking about an actual and acute intertwining of pandemic and insurrection, one anti-colonial, and one white supremicist. Why? I do not have answers, I want to say that right away! But I do think it’s worth thinking more about what the shared condition of vulnerability brought on by a pandemic enables in terms of collective thinking, and what it enables in terms of reconceptualizing who counts as the body politic. I wrote so much in the book about the Indian context, so I would just refer readers to Part I of the book here and use this space instead to add: I think racist white Americans are reacting violently to understanding themselves as existing in the same space—pandemic space, if you will—as the rest of us. It’s inconceivable to them. Anti-maskers, anti-vaxxers, pandemic deniers are saying many things, but one of the things they are saying is: I refuse the “pan” or universality of this condition. It doesn’t apply to me. My body, white America’s body, is not vulnerable. It is immured, immune, it doesn’t need to “hide” behind a mask.

To some extent they are right: the medical racism in this country, to give a very complex set of factors a short name, has made Black, Latinx and Indigenous people leagues more vulnerable to Covid-19. The breach of the Capitol was a ritualized performance of the immunity (to police) and the sovereignty (feet on Pelosi’s desk, the seizing of the rostrum) of the white, able, cis, hetero body. I would be very eager to hear Ed Cohen’s thoughts on this as well, because I think a lot of what he does in that book helps us to understand this moment.

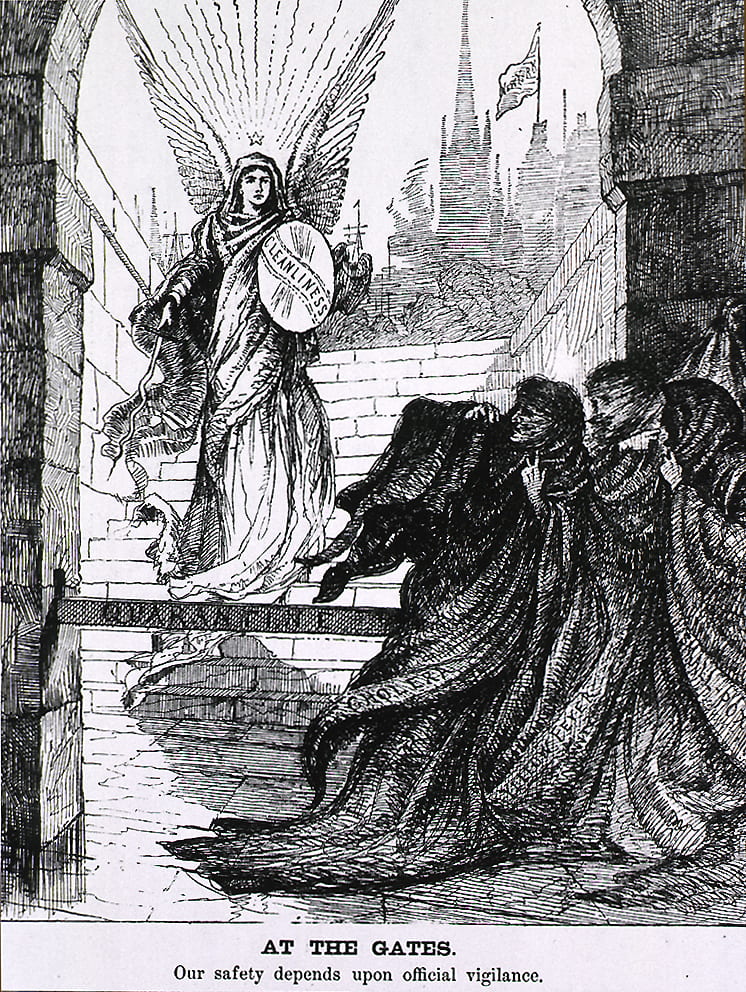

AS: Moving from mobile metaphors to mobile lives, I was wondering if you could say a bit more on how global migration figures into your argument in Epidemic Empire. You allude to it a couple of times throughout the book: certain groups, you point out, are seen as “viral vectors,” and their mobility is marked as pathological and thus dangerous. Most prominently, this nexus is represented by the book’s cover, which features an 1832 painting by Friedrich Graetz where an anthropomorphized cholera is dubbed “the kind of ‘assisted emigrant’ we can not afford to admit.” [see featured image above] But you also address this link through specific historical examples, including Muslim pilgrims in British India and Arab “nomads” in French Algeria. It seems to me that your observations also prove crucial for migrants beyond an explicitly (post-)colonial context, though, with the most prominent example being the twentieth-century refugee who has frequently appeared as a “pathogen” in public discourse and is now regularly conflated with the Islamic terrorist (a fact that has been endlessly exploited by the far-right). How central is migrancy for the “epidemic imaginary” as it emerges from your research?

AFRK: It’s so meaningful to me that you ask this question, particularly because it’s something I’ve continued to study since I finished the manuscript. Reading Erika Lee’s The Making of Asian America, Daryl Li’s The Universal Enemy, and Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States this past summerdeepened my gut feeling that it’s hard to come up with an instance inside the “migrancy” paradigm that isn’t explicitly (post-)colonial. Part of this is terminological. When white Euro-Americans or their descendants in settler states like Australia and New Zealand move around or relocate in the twenty-first century, it’s not understood as an issue of “migration.” This is to do with numbers, it’s to do with the immense wealth hoarded in the states of the Global North and white Oceania, and it’s to do with assumptions about what “people” do, need, and want when they get somewhere. The abiding myths of settler colonialism have not been shaken—white people go somewhere to help, or to establish, or to build, to remedy, to contribute—it’s a selfless act of charity, a “burden” in Kipling’s terms. It is almost never, in the hegemonic languages of history, journalism, and state-sponsored narrative-making, an act of greed or even self-preservation. Israel is in some ways an exception to this rule, but certainly not in all ways, and certainly not since 1956, when an explicitly expansionist imperialist agenda overtook a (dubious) narrative of safety. We use the term migrants for those who are mobile within and because of the legacies of racial capital, religious persecution, and the settler practices that are their abiding methods. That is also to say it’s equally impossible for me to imagine a meaningfully non (post)colonial space on earth as it is to imagine a space on earth meaningfully unimpacted by capitalism. There is no outside—the pockets of resistance are also determined by this immanence.

You’re asking specifically about the twentieth (and I’ll also say twenty-first) century refugee: to compass all these groups in a short answer like this, or even a book or series of books would be impossible, but I’ll describe a pattern and offer two examples I’ve been thinking about lately that help us see, I think, how pathologization is part of the narrative operation that establishes the difference between migrants (Brown and Black people) and—let’s call them jet setters, for fun, or “cosmopolitan” subjects. On patterns: migration and the seeking of asylum and refuge by large groups from Sudan to Ethiopia to Myanmar to Ciudad Juarez to Lesbos are frequently at sites of intensity produced by borders drawn in colonial wars or colonial negotiations—borders that often paid no mind and no respect to existing governance or claims to self-determination. Examples: I’ve been thinking a lot recently about two recent events and wondering how I would have included them in the book, if I had been able to. First, the study released by Brown University Costs of War project, which posits (on the low end) 37 million people displaced by U.S. Wars after 9/11 and a direct death toll of over 800,000. It’s extremely worth spending some time with the resources they put together. In sum, the contemporary “refugee crisis” is a direct result of the War on Terror, and of the pathologization of Muslims and people from what are understood to be “Muslim” countries.

The second thing I’ve been reading and thinking about is the fire at the Moria refugee camp in Lesbos this past summer. The men who started the fire cited unlivable conditions, confinement, the camp as prison; their reasons for burning this hellscape to the ground are, if not defensible, at least understandable—few have moved on from the holding place of the island to mainland Greece and beyond. Few who remained at Moria saw any hope of asylum, let alone a livable life or meaningful work. A small number of Covid-19 cases—reported to be around 35—led to the lockdown of the site. With little available medical care, the camp was certainly a profoundly vulnerable space for a more widespread infection. But the community on Lesbos surrounding Moria was already treating the space like it was under quarantine—calling on Greece to resettle and remove the residents and return life to “normal.”

The catastrophe at Moria requires that we recognize the carceral archipelagos that link us to, say, Japanese internment—but also those in the present. Moria was made to quarantine Muslims from Europe far before Covid-19 cases broke out there. This anticipatory cynicism—as in Trump’s “Muslim ban” and the way it was upheld by the fiction of a regional epidemic—has structured every moment of racial becoming in the white world since 2001, in ways that build on colonial histories of population management and disease containment as justifications for empire. In short: “migrancy” is very central to the epidemic imaginary!

AS: I want to take a moment to also ask about method here, because I think you suggest something really interesting and perhaps, on first glance, counterintuitive in the book. For one, you argue that some administrative modes of colonial bureaucracy and data collection, including the new science of epidemiology, transferred into the literary realm. At the same time, these modes appear to have inspired you as well: to reconstruct a broader cultural narrative, you read across vastly different time periods, geographical regions, and genres and knit together narratives produced by journalists, medical experts, colonial administrators, lawmakers, and politicians to make visible their shared settler colonial heuristic. In the introduction, you call this approach an “epidemiological mode of reading.” But what does it mean to read “epidemiologically,” and which aspect have you found useful to adopt—or perhaps rather co-opt—from the scientific method of analyzing epidemics?

AFRK: For a time, when I was putting the pieces of the book together, this was a really fraught question for me. It was a moment when there was something of a burgeoning in interdisciplinary study in literature and I was taking and teaching courses in the law school, and reading a lot of medical history. A lot of the work coming out of those spaces on the literature side was sort of flat-footed. Much of it still employed pretty straightforward literary close reading methods (New Critical in nature) and aggregated a bunch of instances of lawyers or courtroom scenes in novels, or a bunch of instances of medical practitioners appearing in books and films. In a way, this is good and important—we need the catalogue of scenes, concerns, characters that point outside of feeling and toward a specific practice or training like medicine in the literary archive in order to proceed. But the biggest problem with these approaches was that they were often limited by existing categories of literary history: Victorian studies, or early American literature, and they left the “interdiscipline” largely uninterrogated. New Historicism was a partial exception to this rule, but because of the training of the founders of the field, also very Eurocentric at first. It was mostly (of course, not exclusively) in the already interdisciplinary literature fields—African American and diasporic, Indigenous studies, and postcolonial studies—where better, more adventurous, more consequential work was happening. A few of my teachers published books during these years that I thought of as new gold standards: Joey Slaughter’s Human Rights Inc. (law and literature), Brent Edwards’s The Practice of Diaspora (French, music, and culture), Cristobal Silva’s Miraculous Plagues (medicine and literature). These works created completely new archipelagos of meaning for me. Each of them (and others, as I was starting to learn about and from anthropology at CUNY, specifically Gary Wilder, Talal Asad, Susan Buck-Morss) also interrogated the existing boundaries between fields and the methods of those fields. So I started thinking more methodologically about what was going on in the study of epidemics, and about the foundation of epidemiology.

I wrote in the book about the awkwardness of discovering that “epidemiological reading”—synoptic, multi-regional, a shuttling between close and systems-level analysis—was kind of a good tool for reading what and how I wanted to read. But I worry less about that now. Epidemiology came into being to name and handle a problem that was global, mobile, an effect of empire. So it’s logical that its tools would be useful in studying those effects in the literary and paraliterary archives as well. I’m really glad I put in the work to understand how epidemiologists read and understand their objects, especially in the early days when they were trying to figure it out and give language to their approach. It taught me a lot about the capacities of discourse analysis on the ground, and in the archive. However, to put a very fine point on it: manufacturing a “new” way of reading was an occupational hazard when I was in grad school, and I don’t fret about it as much anymore. It’s not so new, and it’s not so complicated—epidemiological reading is a lot like comparative postcolonial analysis and multi-site discourse analysis. And, like all methods forged in the workrooms of imperial university culture, it has a terrible history (just as the study of English literature does) but has already been profoundly reworked by thinkers who seek to decolonize university epistemologies. I try to honor those thinkers, and, as I say above, follow the object and move it along.

AS: Throughout Epidemic Empire, you stress that the “disease poetics” we are familiar with today were born out of the European colonial project and essentially continued a much older discourse of Orientalism. Beyond the obscuring or outright denying of deliberate political agency on the part of colonial subjects by these poetics, you also point to the limits of the epidemic metaphor as “just a metaphor”—due to the fact that for many, it is a lived reality and part of “a war so long and an attendant discursive regime so pervasive that it restructures every encounter, every memory, appears in every dream.” Bound as it is to underwriting fundamentally imperial epistemologies, do you think there is any “redemption” for the epidemic metaphor? Have you found generative examples of rethinking the politics-disease nexus over the course of your research?

AFRK: I adore this question, and I think about it in new ways every week. The counter-example I talk about most extensively in the book is Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, a novel I think is incredibly complex and smart and sensitive on these subjects. There’s a beautiful storyline in the novel where a political community is brought together by the occasion of a pilgrimage to help heal a woman with breast cancer and a younger woman with epilepsy, who functions as something of a prophet. It isn’t immediately apparent that this is an epidemic allegory—we tend to think of epidemic as a contagious affliction—but the storyline actually theorizes what an epidemic (an event that befalls or is upon the people, from epi (around or upon) and demos (the people)) might be in a more expanded sense. It forces us to imagine non-contagious illness as a social or spreading phenomenon as well, and imagines this occurrence alongside news, belief, action, collectivity. Because it does this so tenderly that the experience of sickness and the attendant group dynamics work, in Edward Said’s terms, to affiliate this group of people. They meet a sorrowful ending, but the message isn’t pessimistic exactly. Later in the novel, another prophet figure speaks about his plans to “tropicalize” London: a recolonization that involves shifted cultural values but also shifted states of presumed health. It’s vengeful and powerful, and again, it doesn’t completely undo the imperial underpinnings of the epidemic metaphor, but it reveals them for what they are: a long-standing justification for ill-gotten riches.

There are other texts and books I didn’t find a way to write about in this book. Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s novel Child of All Nations has an incredibly moving set-piece about a young woman, Surati, who intentionally infects a serial concubine-abuser with small-pox and effectively dismantles a sugar-plantation’s operations in the process. Maryse Condé’s I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem does gymnastic thinking about the Salem witch trials, shared states of vulnerability, the limits of Western medicine, and moral logic in the context of new-world enslavement. Tristan Garcia explores the cultural logics of HIV and AIDS in La meilleure part des hommes,but the character who posits the gift of AIDS and the radical politics of getting and spreading the disease is ultimately treated in a nineteenth-century tragical fashion. The book is well worth reading, but I wouldn’t say it attempts to redeem the metaphor as much as it shows exactly why you cannot, in the face of the intransigence of the body. Mary Shelley does some interesting things with pandemic apocalypse-as-fantasy in The Last Man, which I’ve written about in connection with a diplomatic drama around bird flu here.

Ilya Kaminsky develops a simultaneously allegorical and totally material theory of deafness and revolt in Deaf Republic. I can’t recommend this book more highly, and it is written with such exquisite sensitivity to both contemporary politics and the range of sensory abilities I get teary even thinking about what to say about it. Read it! In the book, I also write a little bit about shared states of disability brought on by the violence of occupying forces in Kashmir (and although I didn’t write about it, Palestine), building on Jasbir Puar’s work in The Right to Maim, and the affiliative capacity of those conditions. While these writers interrogate the ideology in presumed conditions of wellness as a static state (a presumption that has been catastrophic for women, Black and Brown people, disabled people, mentally ill people, neurodivergent people, and the sick), none of them hope for something like health disruptions. So at the heart of what you’re asking is also, I think, an intractable problem—smart theorists and writers play with trying to reveal further and further layers of power and inherited dispositions toward sickness or ability, but these gestures stop short of redemption. What they work to do is to re-conceive non-normative health states as beautiful forms of existence, of flourishing, and at the same time to create more just systems of support for differently abled and sick people. Moving beyond the epidemic metaphor, as a historical function, is what enables this work, I believe.

Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb is associate professor of English at the University of Toronto. She is a scholar of colonial and postcolonial literature and theory with particular research interests in the history of science and intellectual history, poetry and poetics, gender and sexuality studies, political theory and independence movements, the gothic and horror, and comparative literary studies.

Anne Schult is a PhD Candidate in New York University’s History Department. Her current research focuses on the intersection of migration, law, and demography in 20th-century Europe.

Featured Image: “The Kind of assisted emigrant we can not afford to admit.” Political cartoon by Friedrich Graetz, via Wikimedia.

1 Pingback