By Daniel Nelson

Although keeping a journal was a common practice in Henry David Thoreau’s New England, Thoreau’s own journal writing practice, which by the last decade of his life came to dwarf his other endeavors—specifically, his composition of books and essays for publication and of lectures for performance—was a source of bafflement for his contemporaries. After his death his friend and walking companion William Ellery Channing wrote:

His journals should not be permitted to be read by any, as I think they were not meant to be read. […] I have never been able to understand what he meant by his life. Why did he care so much about being a writer? Why did he pay so much attention to his own thoughts? Why was he so dissatisfied with everyone else, etc.? Why was he so much interested in the river and the woods and the sky, etc.? Something peculiar, I judge.

And Emerson, in his eulogy for his former protégé, lamented: “[…] I cannot help counting it a fault in him that he had no ambition. Wanting that, instead of engineering for all America, he was the captain of a huckleberry-party.” Emerson did not mention that those huckleberry parties were one of the myriad subjects of Thoreau’s Journal, whose author, as Channing’s remark suggests, was more interested in huckleberries and the thoughts they provoked than in readers, let alone in “engineering for all America.” (“Patriotism is a maggot in their heads,” Thoreau had written in Walden.) If writing enthusiastically yet indiscriminately about huckleberries, “his own thoughts,” and “the river and the woods and the sky, etc.,” counted as an ambition with Thoreau, it evidently did not with Emerson and Channing.

Taken at face value, the Journal is not problematic. It is, simply, a record — seven-thousand-pages long and twenty-four years in the making — of the author’s daily hikes, observations, reflections, and experiments. What is problematic, as Channing’s and Emerson’s comments suggest, is that the author of Walden and “Civil Disobedience,” a writer and philosopher of great talent and ambition, seems to have devoted his last dozen years or so to the making of this modest-seeming record. I will be arguing that Thoreau was aware of the problem—which we might loosely refer to as the pointlessness of the Journal, its lack of a telos—and that it was inseparable from the shift in thinking and writing that the Journal represented for him. His contemporaries as well as modern-day critics have failed to understand this shift, in large part because so few writers before or since have undergone it. It is the shift toward disinterested writing: writing that lacks “ambition” in Emerson’s sense; that is not for publication but for its own sake, or perhaps, for its subject matter’s sake. As Thoreau put it, “A writer, a man writing, is the scribe of all nature; he is the corn and the grass and the atmosphere writing” (8:441, 9/2/51).

The first and only monograph on the Journal is Sharon Cameron’s 1985 study Writing Nature: Henry Thoreau’s Journal. Cameron, who specializes in game-changing artists (Emily Dickinson, Henry James, and, most recently, Robert Bresson), is a major exception to the rule just mentioned, that critics have failed to understand the mid-career shift in Thoreau’s writing and thinking. (A more recent exception is the French scholar François Specq, who writes: “Thoreau’s Journal is […] fundamentally nonteleological. This is deeply unsettling because it defies both the notion of artistic intent and the idea of practical purposefulness” [385].) Cameron claims that not only did “Thoreau c[o]me to think of the Journal as his central literary enterprise,” he also succeeded in that enterprise sufficiently to produce “the great nineteenth-century American meditation on nature” (3). But the Journal defies readers and scholars, Cameron argues, because it refuses to subject nature to any organizing structure or vision, and refuses, in turn, to organize its own prose. “The wholeness of nature and the wholeness of the Journal,” she writes, “will come to be identical. Yet Thoreau’s idea of totality is […] predicated not on connections but on the breaking of connections. In fact, discontinuity could be described as the Journal’s dominant feature, for no thought is ever entirely jointed to or separated from any other thought” (6). Thoreau’s thoughts seem to be random and going nowhere because nature when viewed unprogrammatically seems to be random and going nowhere. Both “[t]he wholeness of nature and the wholeness of the Journal” reside in our ignorance of—in the mystery of—the logic that binds their parts.

Ten years after Cameron’s book, Laura Dassow Walls proposed a solution to the problem of the Journal. If we cease to think of Thoreau as first and foremost a writer of literature, then his devotion to a text of ambiguous literary status—a text that is pointedly without a point, whose dominant feature is discontinuity—ceases to be enigmatic. Walls’s book, Seeing New Worlds: Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Natural Science, describes connections between Thoreau’s writing and research and contemporary scientific developments, in particular the methodological innovations of the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. More forcefully than previous studies of its kind, it claims that Thoreau’s late writings, including the Journal, belong to the discipline of natural science.

The difference between Cameron’s and Walls’s approach to the Journal is stark. For Cameron, the Journal is an experiment in writing, in serving as “nature’s scribe.” For Walls, it is a tool for studying nature. While there is evidence to support both approaches to the Journal—Thoreau is a phenomenonally complex figure who defies classification—I find that Cameron’s analysis does a better job of capturing what was scandalous about the Journal for Thoreau’s contemporaries, namely, its lack of an identifiable purpose. Whereas Walls (whose view of Thoreau’s late career is by now the standard one among Thoreau scholars) smooths over the scandal by reassuring us of the Journal’s usefulness and importance, I want to suggest that the Journal is non-utilitarian and non-teleological by design, and that by confronting this we can learn something about Thoreau’s understanding of nature—something we miss if we concern ourselves exclusively with his achievements as a naturalist or scientist.

The Thoreau we meet in the Journal is not only indifferent but positively averse to the prospect that any one of his encounters with nature might lead to profit, whether conceived of in literary, philosophical, or scientific terms. He bristles whenever it is suggested that the value of a thing is conditional on its usefulness. His aversion to this instrumentalist conception of value partly explains his abiding love for the shrub oak, with its “scanty garment of leaves” and its “lowly whispering” (9:146, 12/1/56): “A farmer once asked me what shrub oaks were made for, not knowing any use they served. But I can tell him that they do me good” (9:184, 12/17/56).

At issue here is a kind of “good” that is not good for something else—whose goodness is not that of an instrument. Thoreau tries to see each natural phenomenon as belonging to a self-sufficient order of being, hence, as incapable of being lifted out of its context and into that of any humanly conceived and constructed order. “I love best to have each thing in its season only,” he characteristically remarks (9:160, 12/5/56); and he reproves science—which during Thoreau’s lifetime was increasingly moving away from “the field” and into laboratories—for not distinguishing between “a dead specimen of an animal” and “a living one preserved in its native element” (11:360, 9/30/58). In contrast to his non-appropriative manner of dwelling in and with nature, “science,” according to Thoreau’s own definition, is a matter of “what you can weigh and measure and bring away” (1/5/50).

The Journal, therefore, is founded on Thoreau’s conjecture, which grows into a conviction, that “[p]erhaps I can never find so good a setting for my thoughts as I shall thus have taken them out of,” that is, as the setting which is furnished by the Journal’s undiscriminating record of each day’s observed phenomena (3:239, 1/28/52). The entry of the previous day clarifies this insight. To extricate certain thoughts and bring “the related ones […] together into separate essays,” Thoreau writes there, would be an attempt to make good on an experience and a record that is already good, and may be made false (“far-fetched,” not “allied to life”) by attempts at rearrangement, selection, organization—in a word, instrumentalization. The entry concludes: “They [my thoughts] are now allied to life, and are seen by the reader not to be far-fetched. It is more simple, less artful. I feel that in the other case I should have no proper frame for my sketches. Mere facts and dates and names communicate more than we suspect” (3:239, 1/27/52). But they will not thus communicate if, unsuspecting, the writer (or editor, or reader) takes them out of their “proper frame” and tries to make them communicate no more than what he wants them to.

“To walk and work in the woods is like attending a “university,” Thoreau wrote. I suspect a pun here on “universe.” The woods are not the kind of school from which one graduates and goes on to enter the wide world. They are the world, which one returns to, not from:

Had a dispute with Father about the use of my making this sugar [from the sap of maple trees] when I knew it could be done and might have bought sugar cheaper at Holden’s. He said it took me from my studies. I said I made it my study; I felt as if I had been to a university.

It dropped from each tube about as fast as my pulse beat, and as there were three tubes directed to each vessel, it flowed at the rate of about one hundred and eighty drops in a minute into it. One maple, standing immediately north of a thick white pine, scarcely flowed at all, while a smaller, farther in the wood, ran pretty well. The south side of a tree bleeds first in spring. I hung my pails on the tubes or a nail. Had two tin pails and a pitcher. Had a three-quarters-inch auger. Made a dozen spouts, five or six inches long, hole as large as a pencil, smoothed with a pencil. (8:217-18, 3/21/56)

“He said it took me from my studies. I said I made it my study.”

The “it” here is not nature—the “studies” to which Thoreau’s father refers was precisely his work as a naturalist—but rather things: trees, sap, tubes, pails. The shift toward disinterestedness that I have been discussing in Thoreau’s career was a shift toward valuing things and away from using them, whether for the purposes of science or art or philosophy.

Plainly, syrup-making was for Thoreau not a final purpose but an intermediate one: not a telos but a kind of anti-telos. Like his other minor projects (gathering driftwood, taking measurements, conducting unsophisticated experiments, collecting local lore), it was a means of avoiding the more conventional, grander purposes that his father and Emerson urged upon him. But this negative work of avoidance was part of a positive project of keeping himself open, “comprehensive,” his energies and identity uncircumscribed. Whereas Emerson faulted him for lacking ambition and the drive to succeed on a grand scale, he faulted Emerson for lacking “a comprehensive character”: for succeeding too much in one direction. “I doubt if Emerson could trundle a wheelbarrow through the streets,” he wrote in the Journal, “because it would be out of character. One needs to have a comprehensive character” (9:250, 1/30/52). For Thoreau, to have a comprehensive character was to be at ease in the company of things no less than in the company of people: to be unashamed of the former’s company when walking through the streets, and unencumbered by the latter’s company—not so much their physical presence as the pressure of their expectations—when walking through the woods.

Daniel Nelson, who studies 19th century American literature, received his PhD from the University of Rochester.

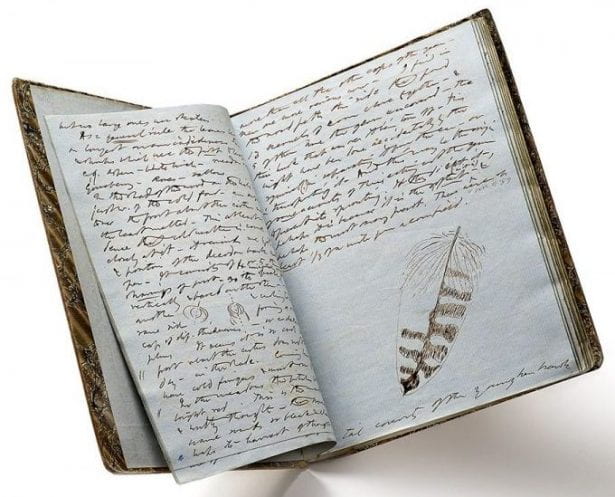

Featured Image: Manuscript volume of the Journal [The Morgan Library and Museum], courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum.

February 21, 2021 at 6:52 pm

Hi Daniel,

I enjoyed your article, although I was a bit confused by the conclusion, and I was wondering if you could clarify.

You write:

“Plainly, syrup-making was for Thoreau not a final purpose but an intermediate one: not a telos but a kind of anti-telos.”

What is an anti-telos?

It seems to me like you are saying that syrup-making was an activity valuable to Thoreau intrinsically, and also because it served the final end (the telos) of creating a comprehensive character. Is that what you mean by “anti-telos”?

February 22, 2021 at 1:05 pm

Hi Christopher: Thank you for your comment. You’re right, I am saying that “syrup-making was an activity valuable to Thoreau intrinsically.” As for creating a comprehensive character being his final end or telos, I suppose it’s fair to say that comprehensiveness was Thoreau’s final end–but it’s also a bit paradoxical, much as the notion of an “anti-telos” is a bit paradoxical. To say anti-telos is to speak of the presence of an absence, or perhaps, of an avoidance: the absence or avoidance of telos. Likewise, to say that Thoreau’s purpose was to have a comprehensive character is akin to saying, somewhat paradoxically, that his purpose was to avoid having a purpose–at least, a particular, overriding purpose–so that he could remain open to a wide range of different (minor) purposes, activities, ways of thinking. So, in the case of syrup-making, I take it to be self-evident that he did not consider this activity to be any more enlightening or worthwhile than the dozens of other activities he engaged in and described in his Journal. Making syrup was for him a means (one of many that he hit upon) of approaching and engaging with nature that de-emphasized the very question of purpose, and the related questions of significance, importance, etc. He deliberately didn’t ask himself, while collecting the syrup, what the purpose or meaning of this activity was; by keeping his hands and his mind busy with this work, he remained focused on the multitude of things (the trees, the sap, the tools he uses) rather than on any end to which these things might be the means.