Jonathon Catlin

I was fascinated by a short piece for Public Seminar by William E. Scheuerman, a scholar of Carl Schmitt and his Frankfurt School critics, which reflects on the paradox that in Schmitt’s view, “Democracy’s realization can legitimately take authoritarian forms,” such as plebiscites and sham elections. As Scheuerman explains, Schmitt argued that democracy (narrowly conceived as homogeneous political identity) and liberalism (narrowly conceived as preserving individual liberties) are not only different but fundamentally antagonistic. This view has returned from the dustbin of historical ideas in Hungarian leader Victor Orbán’s proud affirmation of “illiberal democracy”—a notion Jan-Werner Müller has argued is self-contradictory. Eschewing the “fascism debate,” Scheuerman argues that Trump remained—disturbingly—within the realm of democratic practice, however exclusionary and illiberal his actions may have been: “Authoritarian populists such as Trump hollow out democracy while mimicking its language and sometimes its forms. They practice staged or phantom democracy.”

The historian Robert Gerwarth similarly argues in his piece “Weimar’s Lessons for Biden’s America” that while direct analogies between Trumpism and fascism do not stand up to scrutiny, if Weimar offers one lesson it “is that it is fatal for conservatives to think that they can play with the fire of right-wing extremism without getting burned. Trump is no Hitler, but his deliberate mobilization of the far-right has made the Republican Party dependent on voters who include militant nationalists, Holocaust deniers, white supremacists, and conspiracy theorists—in short, people who want more than just a different government.”

Finally, in Jacobin, historian Matt Karp argues that the present “American political situation portends much scattered violence, but nothing that resembles either civil war or fascist coup.” Rather, he argues that the best historical analogy for understanding the present moment is the Gilded Age, which similarly locked American politics in identity-based partisanship and prefigured the present “class dealignment” of political parties that became strikingly clear in the results of the 2020 election: upper-middle-class suburban whites flocked to the Democratic Party to remove Trump from office, but on the same ballots voted against substantive policies like progressive taxation. In the reverse direction, Karp notes, one working-class county in Florida voted overwhelmingly both to raise the minimum wage to $15 and to reelect Trump. While all three authors argue that removing Trump from office hardly ensures the security of American democracy in the years to come, Karp notes that the democratic process is thriving in at least one sense: “More than two-thirds of eligible voters cast a ballot this fall, making 2020 the highest-turnout election since 1900.”

Max Norman

I have been sampling from A Dictionary of Symbols, by the Spanish artist, aesthete, and latter-day humanist Juan Eduardo Cirlot, recently reprinted by New York Review Books. Cirlot took to symbology in order to understand the ancient roots of the symbols that animated the twentieth-century avant garde: the crosses, hourglasses, skeletons and the like that modern artists took from the tradition like so much ancient spolia. Weaving together Jungian psychoanalysis and 20th century Geistesgeschichte, Cirlot writes a kind of encyclopedia of the tradition, with miniature essays on topics from ‘abandonment’ to the Zodiac. It’s a work whose grandeur and fascination approaches that of Benjamin’s Arcades Project and Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas. Caveat lector: reading before bed may cause Surrealist dreams.

Simon Brown

Earlier this week, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who published and publicized and represented his Beat generation of poets, died in San Francisco. He helped to found City Lights, the bookstore and printing house that was sued for obscenity when it published Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. It is an icon and fixture of the Bay Area literary world. It also represented the San Francisco that I imagined before I moved to the East Bay in 2015. If you live in Berkeley or Oakland or elsewhere across the Bay, you spend a lot of time—usually unintentionally —looking over at San Francisco and, by extension, thinking about it. On one hand, it makes sense to think about its successive migrations—of Chinese workers, Queer runaways, and now tech workers—since the early twentieth century. There is also the implacable view that Ferlinghetti himself gave in his poem (“The Changing Light,” 2005), of a place recognizable by its natural light:

The light of San Francisco

is a sea light

an island light

And the light of fog

blanketing the hills

drifting in at night

through the Golden Gate

to lie on the city at dawn

Nathan Heller, writing recently for The New Yorker, described “the Northern California style of intellection,” in which writers like Joan Didion have “pinned their ideas to details of landscape,” to escape endless abstraction. The light of San Francisco attracts that style, and makes it hard to look elsewhere. Ferlinghetti captured that and much more of the city.

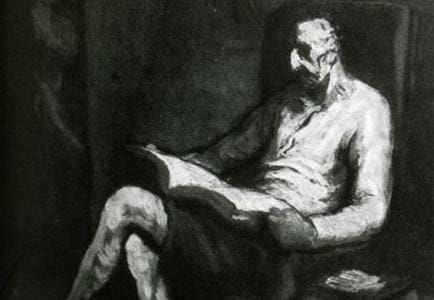

Featured Image: Don Quixote Reading. Honore Daumier, c. 1865 – 1870.

1 Pingback