By Avery Weinman

Archival work is my bread and butter. Throughout the fall of 2020, I spent a majority of my time researching Eliyahu Beit-Tzuri and Eliyahu Hakim: two Palestinian Sephardi members of the extremist Zionist terror organization Lohamei Herut Israel (also known by its Hebrew acronym, Lehi). On November 6, 1944 in Cairo, Beit-Tzuri and Hakim assassinated Lord Moyne, who, as the British Resident Minister of the Middle East, was one of the highest-ranking officials in the British Empire in the Middle East and North Africa. The assassination thrust the British-Zionist conflict in Palestine to the forefront of the international imagination, and the reverberations from the assassination and subsequent trial both accentuate the importance of Beit-Tzuri’s and Hakim’s Sephardi identities and situate Zionism alongside other anti-imperial national liberation movements of the early-to-mid twentieth century. As I sifted through Hebrew, French, and English newspapers from the mid-1940s, court transcripts from Beit-Tzuri’s and Hakim’s trial in Cairo, their letters to home, fiery propaganda issued by Zionist terror cells, and interior memos of the British Foreign Office, I was filled with the buzzy delight that characterizes how I feel working with primary sources. It was only in the brief moments of unexpected interruption—in which the alarm for my lunchtime baked potato went off, or my laptop chirped that I had ten minutes until my umpteenth Zoom meeting of the week—that I remembered how deeply removed I actually was from traditional archival work.

Since the spring of 2020, archives all over the world have closed their doors in accordance with quarantine measures designed to impede the spread of COVID-19. These conditions are, to put it mildly, a profound challenge to historical research. But these challenges are not without their silver linings, the potential benefits of which are especially visible in the Israeli archives I used while researching Beit-Tzuri and Hakim. While state and state-adjacent institutional backing typically determine the legitimacy of Israeli archival sources, coronavirus-related closures have brought digital accessibility to the fore as a newly significant factor in historical archival research. The abnormal circumstances of archival work in the coronavirus era, which restricts historians almost entirely to the digital space, acts as a sort of hyper-fertile incubator that accelerates historians’ inquiries into the idea of archival work, which archives count, and, ultimately, whose voices get heard.

Archival theory and historians’ investigation into archives themselves well predate the absurdity of 2020. As part of the post-colonial, post-structuralist wave that began in the mid-twentieth century, historians have expanded their understanding of the archive beyond a mere container for data to what Ann Laura Stoler memorably coined “archives-as-things” in her 2009 monograph Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Here, Stoler identified and analyzed the palimpsests of colonial anxieties about race, gender, and power as they appear in archival documentation from the nineteenth-century Netherlands Indies to unveil archives themselves as dynamic expressions of historical processes. In addition to Stoler’s establishment of the archive as a site of historical inquiry, Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s 2015 article “Black Holes, Dark Matter, and Buried Troves: Decolonization and the Multi-Sited Archives of Algerian Jewish History” and Diana Taylor’s 2010 article “Save As… Knowledge and Transmission in the Age of Digital Technologies” raise questions into the role of the archive that have been sharpened by the era of coronavirus. Stein shows that who has the legitimate “right” to archival material and what kinds of archival materials different players seek to control indicate how historical actors use the conquest dimension of the archive to exert authority over the historical narrative. In Stein’s piece, four distinct actors—Algeria, France, Israel, and the Mzabi Jewish community from southern Algeria—competed to possess Mzabi Jews’ archival trail. Both in a literal sense by attempting to collect and house Mzabi documentation, and in a symbolic sense by moving to weave the Mzabi Jewish past into their own narratives, each rival party sought to nationalize, colonize, liberate, or localize Mzabi records to substantiate their own claim as the authentic heirs of Mzabi Jewish history amidst the upheavals of post-colonial independence in the mid-twentieth century. Their four-way tug-of-war prompts historians to consider the problem of dominion over archival materials, and to question the ideologies behind where archival materials are located. Taylor studied the digital archive specifically, and concluded that digitization and twenty-first-century technologies have fundamentally redefined what an “archive” is and can be by democratizing access to and construction of archival (web)sites. According to her, these technologies have transformed which kinds of materials are worthy of archival documentation, eroded the notion of archival ownership or copyright, and deracinated archival sites from physical space and capital. While each of these works predated the coronavirus pandemic, the questions Stoler, Stein, and Taylor have posed are especially potent in a time when being restricted to the digital realm further magnifies the form of archives themselves. My own research experience with Israeli archives this past fall exemplified the renewed relevance of these scholars’ analyses, as historians’ temporary relegation to the e-archive have overturned the pre-existing hierarchy of Israeli institutional archival legitimacy.

Divisions between different Zionist factions siloed whose histories went to which Israeli archives along political lines. This was especially true for the bitter, and often violent, rivalry between the Labor Zionists and the Revisionist Zionists. The Labor Zionists dominated the political landscape of both the pre-state Yishuv and the initial decades of Israeli state sovereignty, from the early twentieth century through the late 1970s. Conversely, the Revisionist Zionists were relegated to the fringes of Zionist and Israeli politics and governance. As Israeli historian Amir Goldstein explains in his 2015 article “Olei Hagardom: Between Official and Popular Memory,” the Labor Zionist establishment led by David Ben-Gurion and the Mapai party at the beginning of Israeli statehood were acutely aware of the political power that came with their ability to use institutional legitimacy to curate Israeli collective memory. By privileging their own activities in archives, museums, and ceremonies, while obscuring the presence of their Revisionist Zionist rivals, Mapai formalized a decades-long precedent of political marginalization through institutional exclusion. In so doing, Mapai fixed the parameters for what kinds of politics would be considered legitimate in the Israeli sphere for decades to come. To cement their own position as the hegemon of Israeli state power, the Labor Zionists excluded, redacted, and erased the presence of their political rivals—most notably the Revisionist Zionists, but also the Israeli Communist Party as well—from the archival bodies of state and state-adjacent institutions.

Israeli scholar Tuvia Friling articulates both the process and the consequences of this exclusion of Revisionist Zionist voices from the archive and Israeli historiographical narrative in his 2009 article “A Blatant Oversight? The Right-Wing in Israeli Holocaust Historiography.” Examining the “lacunae” of writing about Revisionist Zionist efforts to facilitate so-called illegal immigration to British Mandatory Palestine following the enactment of the 1939 White Paper, Friling explains that the Labor Zionists at the head of the newly created state of Israel quickly mobilized “sweeping historiographical enterprises to secure their version as the canonical narrative of national rebirth.” In other words, in spite of the fact that Revisionist Zionists’ role in facilitating Jewish immigration was well-known among the population of British Mandatory Palestine, the state expunged records of their activities from institutionally legitimized archives. As a result, Revisionist Zionists were, and remain, overwhelmingly absent from both popular commemoration and Israeli historiography of Jewish immigration in this formative period of national myth-making.

Revisionist Zionists did attempt to set up their own institutions and archives in response to neglect in state interest and state funding. However, because of infighting between different Revisionist Zionist factions and predilection towards mythification and privatization within the ideology of Revisionist Zionism itself, these institutions and archives opened slowly and without the necessary organizational unity required to make a meaningful intervention into the historical narrative. For example, The Lehi Museum in Tel Aviv did not open until 1991. The Menachem Begin Heritage Center, which enjoys a greater degree of political recognition, only began collecting archival materials in 2000. The state of Israel officially recognized the archives of the earliest and most established of Revisionist Zionist bodies, the Jabotinsky Institute, in 1958, but Friling asserts that even the Jabotinsky Institute “remained an isolated island in the ocean of institutes connected in various ways with the leftist camp.” It is one of the peculiarities of Israel that, even four decades after the Revisionist Zionists achieved mainstream political success with the Likud Party’s first victory in the 1977 elections, Revisionist Zionism remains peripheral to the dominant historical narrative and structures of the state.

Eliyahu Beit-Tzuri and Eliyahu Hakim were both members of the Lehi, meaning I relied on marginalized Revisionist Zionist archives—especially the Jabotinsky Institute—to conduct my research. State and state-adjacent institutional archives like the Central Zionist Archives or the Israel State Archives have few, if any, relevant sources on Beit-Tzuri’s and Hakim’s actions and lives. Because of coronavirus-related closures, my main consideration in conducting meaningful research was online access to digitized material. Fortunately, I discovered quite quickly that the Jabotinsky Institute hosts a veritable treasure trove of digitized content on its website that is free to access for anyone with an internet connection. For my research, this archival body yielded an abundance of photographs, letters, newspaper articles, propaganda publications, transcripts, and commemoration pamphlets about Beit-Tzuri and Hakim, their roles in the assassination of Lord Moyne, their trial in Cairo, their executions in March of 1945, and the resonance they would ultimately leave in a hotly contested landscape of Israeli collective memory. With supplementary sources from the extensive collection of historical newspapers provided through the National Library of Israel, I conducted rigorous archival research akin to the standards of working in a physical archival space—all while sitting comfortably at my desk in my tried-and-true Adidas sweatpants.

Working entirely digitally allowed me to conduct this research with relative ease, and to bypass the hierarchy of Israel’s politically siloed archives. This fact, in turn, has prompted me to consider if the crucible conditions of archival work in the era of coronavirus closures have actually created an accelerated democratizing process that casts which archives are considered institutionally legitimate and which histories get told into sharp relief. As Goldstein and Friling point out, the Revisionist Zionist archives I relied on typically fall outside the boundaries of institutional legitimacy. However, because those sources are digitized and easily accessible, Revisionist Zionist archives benefit from the leveled playing field brought about by the unusual circumstances of the pandemic. This strange period in time in which digital access outranks institutional endorsement encourages historians to work with archives they might have otherwise overlooked. My experience researching Beit-Tzuri and Hakim was specific to Israeli archives, but the accelerated process of democratization enabled by digital accessibility applies broadly to archival work across fields of study. How does “doing history” change when unexpected challenges recalibrate which archives historians can even use? Can this moment, as frustrating as it is, instruct historians in how to better include marginalized voices? Can it embolden historians to challenge the notion that institutional backing is synonymous with historical legitimacy? These prodding questions into the idea of archives themselves predate the era of coronavirus closures, but I would optimistically hope that historians can extract a silver lining from this enforced digital age to turn a challenging time into an opportunity to examine the archive with renewed zeal.

Avery Weinman is a graduate student in the UCLA Department of History and the Harry C. Sigman Graduate Fellow at the UCLA Y&S Nazarian Center for Israel Studies. Her main areas of focus are modern Jewish history, Sephardi/Mizrahi Studies, the history of modern Israel, the history of the modern Middle East and North Africa, and the intellectual history of Zionism. Currently, she is intensely interested in the activities and worldviews of Sephardi and Mizrahi members of the Irgun Zvai Leumi and Lohamei Herut Israel in the 1940s during the British Mandate of Palestine.

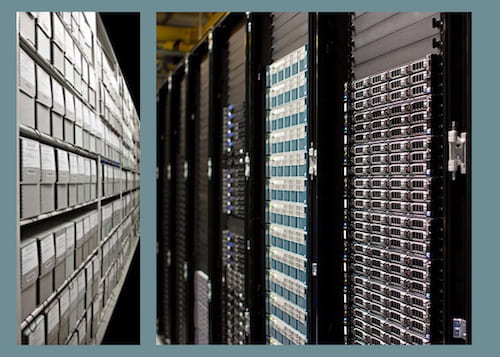

Featured Image: Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Interior shot of the storage facilities at the Archives of American Art’s Washington, D.C. headquarters. June 1, 2011. Accessed February 8, 2021. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. | Victor Grigas. Wikimedia Foundation Servers. July 16, 2012. Accessed February 8, 2021. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.