By Till Wagner

The position of public intellectuals today is a contested one. On the one hand, they play a significant role in the public deliberation of social and political affairs; on the other hand, there is persistent skepticism toward their perception of the present, based on the widely held sentiment that it is inherently disconnected from reality—that, in short, it is nothing more than an observation from the top of the “ivory tower.” In right-wing attacks against intellectuals, the latter are accused of representing an elitist, biased, and ultimately unrealistic view of society and current affairs.

This populist anti-intellectualism is by no means of recent origin: Already in his 1967 lecture “Aspekte des neuen Rechtsradikalismus” (“Aspects of Contemporary Right-Wing Radicalism”), Theodor W. Adorno noted the central role of anti-intellectualism in right-wing ideology. Hinting at its structural similarity to antisemitism, Adorno considered anti-intellectualism an ideology that perceives the intellectual

as a kind of vagrant in life, an ‘air person’ [‘Luftmensch’]. According to this ideology, whoever does not participate in the division of labour, whoever is not bound by their profession to a particular position and thus also to quite particular ideas, but has instead preserved their freedom of spirit, this person is a kind of rascal who needs to be brought into line.

Adorno, “Aspects of Contemporary Right-Wing Radicalism,” 13

Such undifferentiated populist and right-wing ressentiment against intellectuals, which presents one current in the ongoing attacks on academia, science, and the press, at times obscures the fact that self-critical reflection is an integral part of intellectualism itself. This is discernible in both Jean Améry’s and Hannah Arendt’s retrospective analyses of the rise of National Socialism and their critique of the passivity exhibited by some of the time’s most influential intellectuals. Not only do their respective reflections about said passivity and its causes give insight into their philosophy, but they also resonate in the crisis-ridden present in which the value of humanistic thinking may altogether appear questionable.

The biographies of Arendt and Améry show significant parallels: Both were born before the First World War ended, both had to flee National Socialism, both attempted political resistance in some form, both were interned in the camp at Gurs for a while, and both made their experiences an object of their intellectual reflection after the war. Though their respective philosophies are marked by at times sharp contrasts—Améry, for instance, was very critical of Arendt’s concept of a “banality of evil,” which the latter famously developed in her book about the Eichmann-trial in Jerusalem—there are definitive parallels in the critical, intellectual self-reflections they developed in two essays, despite those essays being published more than thirty years apart.

Arendt’s “Portrait of a Period” (1943) is a critical review of Stefan Zweig’s memoir The World of Yesterday, an account of the personal and artistic path of the Austrian novelist, journalist, and playwright, and a depiction of prewar Austria-Hungary and Europe from Zweig’s own perspective. To Arendt, Zweig’s nostalgic—and, in light of Zweig’s suicide in 1942, quite tragic—autobiography is the manifest of a humanistic but in the end apolitical thinker, who was so entrenched in his own social circle that he made himself at home in a world that provided emancipation only to the famous. According to Arendt, Zweig thus experienced the rise of National Socialism in Europe not as a historical and hence inherently political and societal development, but rather as a natural catastrophe.

A similar sentiment is formulated in Améry’s “Von der Verwundbarkeit des Humanismus” (“On the vulnerability of humanism”), which was first published in 1981, three years after Améry took his own life, in the anthology Bücher aus der Jugend unseres Jahrhunderts (“Books from the youth of our century”). In the essay, Améry also takes Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday as the starting point for his reflection on the humanistic intellectual in moments of crises. In contrast to Arendt, though, Améry does not dwell on Zweig but quickly transitions from The World of Yesterday to Romain Rolland, the French novelist, pacifist, and 1915 Nobel Laureate who was a close friend of Zweig, and his magnum opus Jean-Christophe. In both the author and his work, Améry recognizes the titular “vulnerability of humanism.” To him, this vulnerability is marked by a pacifistic attitude fixated on high culture, obsessed with arts, aesthetics, and high values. In its inwardness and gentleness, Améry argues, the vulnerable humanism of Rolland shies away from action, loses sight of reality, and “finally fails in a world in which even humanity must arm itself.” (490) Rolland’s humanism, Améry concludes, is apolitical in the end—and thus ineffective.

The similarity between Améry’s reflections about “vulnerable humanism” and Arendt’s critique of Zweig should not obscure the conflicting theoretical underpinnings of both texts. As Seyla Benhabib points out in The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt, Arendt’s biography of Rahel Varnhagen, which she completed while living in exile in Paris in 1938, offers a key to her political thinking. Varnhagen was a German writer during the late 18th and early 19th centuries who hosted an influential salon and was Jewish by birth but later converted to Christianity. Using the categories of the Pariah and the Parvenu in the biography, Arendt describes Varnhagen’s ambivalent relationship with her Jewish origin amidst the struggles of assimilation and aspired emancipation and analyzes her transformation from an ideal-typical Parvenu, who tries with all strength to adapt to the majority society and thereby self-denyingly rejects her own identity, to a Pariah, who, having come to terms with her own identity, is able to turn it from a social flaw into a form of individual resistance. Yet Arendt also criticizes a mode of interacting with the world that she considers a prominent feature of Varnhagen’s cultural and intellectual engagement with the world: “Innerlichkeit,” an introspective way of thinking and understanding, which is mostly concerned with subjective feelings and emotions. Indeed, in the book Arendt argues that this attitude leads to a confusion and, eventually, neglect of the boundaries between the private and the public sphere that she considers crucial for genuine political action, which presupposes mutuality in the shared public sphere.

This differentiation between the Parvenu and Pariah, together with her profound critique of a nonpolitical “Innerlichkeit,” can be seen as the key element of Arendt’s critique of Zweig. From this perspective, her condemnation of Zweig’s withdrawal into a “sanctuary” secluded by “very thick […] gilded trellises” (319) emerges from her idea of the Parvenu: it is Zweig’s way of positioning himself as an ideal-typical Parvenu who achieved individual emancipation by fame and success while at the same time not reflecting his own identity, which first abets a delusional perception of reality and then consequentially leads to living the apolitical life lamented by Arendt. This backdrop of Arendt’s critique also becomes apparent in the way she analyzes Zweig’s nostalgic depiction of prewar Europe, which interweaves descriptions of arts and culture with articulations of his subjective feelings and thus invites comparison to the “Innerlichkeit” of Varnhagen.

While for Améry, Jewish identity also proved an important topic throughout his work—he discusses the experience of being “made” a Jew by the Nazis as an atheist with little knowledge about Jewish culture in his essay “On the Necessity and Impossibility of Being a Jew”, for example—it does not constitute the underlying theme of his critique of “vulnerable humanism.” For him, it is not Romain’s personal withdrawal into a secluded elitist cultural sphere, or his denial of a forced identity and concomitant desire to fit into a society that is hostile toward him, but rather his model of humanism that forms the object of critique.

Born as Hanns Chaim Mayer in Austria, Améry felt at home in both the rural area of the Salzkammergut and existential philosophy with its focus on nature and its yearning for authenticity throughout his youth. In his autobiographically inspired essay collection Unmeisterliche Wanderjahre (“Unmasterly wandering years”), Améry looks back on this youthful affection and his following enthusiasm for the Logical Empiricism of the Wiener Kreis as submissions under different systems of thought that nevertheless proved delusional in their own ways: neither one of the two, Améry argues, takes the reality of society or history into account when formulating a comprehensive understanding of the world.

This self-critical retrospective is strongly informed by Améry’s own experience of being persecuted, interned, and tortured in different National Socialist concentration camps in the 1940s. In his essay “At the Mind’s Limits,” he reflects on the intellectual in Auschwitz and describes how neither analytical thinking nor an aesthetic understanding of the world were of any value in the brutal universe of the camp because they had lost their basis in social reality. Améry thus concludes that the camp internment provided the intellectual who was lucky enough to survive with a profound “philosophical disillusionment, for which other, perhaps infinitely more gifted and penetrating minds must struggle a lifetime.” (20)

A subjective experience of suffering is central to Améry’s essayistic writing and foundational for his sharp, concise, and sometimes painfully honest observations. Indeed, it is the experience of a “philosophical disillusionment”—the realization, that thought must correspond to (social) reality in order to be meaningful—that shaped not only his retrospective assessment of his own early philosophical leanings, but also his critique of “vulnerable humanism.” For Améry, a humanistic intellectualism that is constrained by its own system of thought ultimately inhibits an active and politically meaningful stance toward the world. This insight is the basis from which Améry criticizes the dreamy and hopeful worldview of Rolland’s Jean-Christophe, which in his eyes amounts to a denial of reality and effectively undermines Rolland’s humanistic intentions.

Considering their similar biographies, it comes at no surprise, then, that both Arendt and Améry emphasize the importance of the critical intellectual as a cautious observer of society and politics. Precisely because of this shared, historically conditioned awareness, both warn of the pitfalls inherent in a self-isolating intellectualism.

Their seemingly similar positions, however, are developed on the basis of rather contrasting theoretical approaches that shed light on the distance between both thinkers: while Arendt focuses on issues of social positionality, identity, and their influence on the ability to understand social reality, Améry is concerned with delusional aspects of humanistic intellectual thought itself. The distances that come to light when looking at their argumentative affinities in detail demand from us a more intense practice of reading and understanding, which takes the philosophical roots of superficial argumentation into account. Hopefully, Améry’s and Arendt’s rejection of the flight into illusory worlds and the corresponding blindness towards social and historical reality will be heard—it has not lost its relevance.

Till Wagner is a Master’s student at the Center for Research on Antisemitism, Berlin and has a background in history and political science. He works on the history of antisemitism, on Critical Theory and political philosophy after Auschwitz, and on the transformations of racism and antisemitism in the Digital Society.

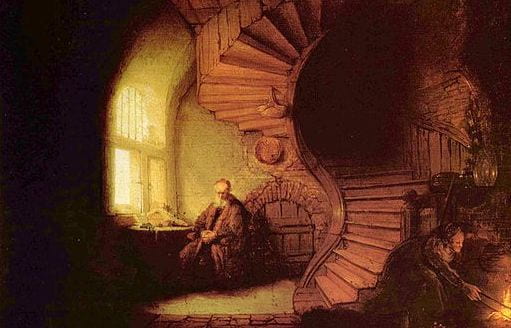

Featured Image: Philosophe en meditation, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1632