By Gordon Finlayson

In his new book, Migrants in the Profane, and in a recent interview on this blog, Peter E. Gordon addresses questions about Adorno and negative theology which I address in my own work on Adorno (2002 & 2012). Though we agree there is an analogy between aspects of Adorno’s negative dialectics and negative theology, we differ on significant points that I will attempt to bring into sharp focus. Put briefly and crudely, I hold that negative theologians are more philosophical, and Adorno’s critical theory less theological, than Gordon maintains.

Our specific disagreements concern:

- what via negativa is – that is the procedure of denial or negation (apophasis) that negative theologians deploy, and to what end they do so

- how far, and in what respects, this is analogous to Adorno’s philosophy

My view is that there is an analogy between Adorno’s conception of the task of philosophy, which is to think what is non-identical to thought, and certain doctrines of negative theology concerning the human inability to describe, express, or know God’s essence or nature. The analogy holds only if one construes the non-identical in Adorno strictly as “the figure of something wholly beyond reason and completely other to discursive thought and hence unknowable and ineffable” (Finlayson, 2012, 4). Some, like Elizabeth Pritchard (303), reject this interpretation of non-identity in Adorno, on the grounds that he says in his Negative Dialectics that “metaphysics cannot … be conceived after the mode of an absolute otherness terribly defying thought”(407). Indeed, Adorno frequently denies that the non-identical is not wholly transcendent and ineffable. The trouble is he just as often says that it is. Since the textual evidence is ambivalent, I take the following to be decisive. Adorno conceives non-identity as what is non-identical to thought. By Adorno’s lights, thought is conceptual. To think is to use concepts, and to use concepts is, ineluctably, to identify. There is no such thing as non-conceptual thinking and so we cannot so much as conceive of what is non-identical, let alone say what it is. It follows that Adorno’s Negative Dialectics can be understood as a way of addressing the paradox of the ineffable. This interpretation of Negative Dialectics is not forced, because Adorno himself more than once refers to the non-identical as “the ineffable” and claims that the central concern of philosophy, is to try “against Wittgenstein to say what cannot be said…The task of philosophical reflection consists in unravelling this paradox.” (21).The analogy with negative theology holds, then, not because there is a theological dimension to Adorno’s thinking, which, pace Angermann, I deny, but because Adorno’s central thesis that the concern of philosophy is to think what is non-identical to thought faces the same philosophical difficulty as negative theology does in its attempt to talk about, and to know, a God that is wholly transcendent.

Gordon accepts the analogy between Adorno’s philosophy and negative theology but claims that it “ultimately breaks down”. I agree it breaks down in the sense that it is, in the end, only an analogy, not a thoroughgoing similarity. But we differ in our judgments of where the analogy breaks down. According to Gordon “Adorno pursues the via negativa to liberate us from the illusions of ideology, but he does not stop short before any kind of final or metaphysical truth. Instead, he … pursues it (the negative) right into the heart of theology itself where it dissolves the metaphysical object it was originally meant to serve. He would loathe the thought that this negativity is only a passing moment on the way to reconciliation.” So Gordon argues that, in spite of their best attempts not to, negative theologians end up affirming a “metaphysical truth” presumably concerning God’s existence or nature. They thus aim at “reconciliation.” Adorno, by contrast, remains consistently negative.

While I accept that negative theologians believe in God, and Adorno probably doesn’t, I reject the stark contrast that Gordon draws. Gordon’s claim (53) about Adorno, resembles Scholem’s claim about Judaism, that it is more negative than negative theology. I think the difference is vanishingly small. For the negative theologians, while they assume (or argue) that God exists, insist that God’s existence and divine nature are completely unknowable. Most acknowledge, as Augustine and Basilides also do, that even statements such as that God exists, or that God is ineffable and unknowable, already say too much.[1] They also claim that apparent assertions about God can be understood as disguised negations. But this is merely a way of showing that God’s attributes, say God’s goodness, are incomparable with human attributes and human goodness. They hold that one cannot come to know God either by way of assertion or by way of negation. To the extent that there is no way to God, there is strictly speaking no ‘negative way’ either.

We should not conflate this view with a thought that can be found, for example, in the neo-Platonist, Plotinus. Neo Platonism, which insists that the One is beyond being, and unknowable and ineffable, has a close affinity with negative theology. Plotinus claims that we can sculpt the self by removing what is bad, or vicious or imperfect in ourselves, and that in this way, like the sculptor, human beings can achieve perfection and reach the idea of the “Good that lies beyond” (I, 69) Now there is an obvious incoherence in thinking of negative theology like that. Although it works by subtraction, or negation, it is not negative in its result. To my knowledge, none of the negative theologians, Maimonides included, make this mistake. They know that the via negativa, is not a way to godliness, to God, or to knowledge of God. Take Eckhart, for instance: “If a man thinks he will get more of God by inwardness, by devotion, by ecstasies, or by special infusion of grace, than by the fireside or in the stable, that is nothing but taking God, wrapping a cloak round His head and shoving Him under a bench. For whoever seeks God in a ‘way’ gets the way and misses God, who remains hidden in the way’.[2] Negative ways are no different than any other way, like asceticism or mendicancy. They are ways of living a human life. To assume they are ways to God is to commit the sin of idolatry. Similarly, negative propositions won’t bring us any closer to knowledge of God. So even the claim that God exists stands outwith the bounds of the knowable and the effable. And with that thought negative theology subverts its own status as a discourse to/about/from God. Hence, I disagree with the conclusion that negative theology ultimately aims at a “metaphysical truth” or to “reconciliation” with God. This conception of negative theology is too positive and too close to theism.

I accept the claim that Adorno’s negative dialectic is more negative than negative theology in that it does not imply the existence of God. But the salient question is: does Adorno’s negative dialectics imply the existence of the non-identical? It is not obvious that the answer to that question is No!

Even if it is, Adorno’s negativism is not as rigorously and consistently negative, as Gordon supposes. Some programmatic statements of Negative Dialectics verge on incoherence, for example that the central concern of philosophy is to try “against Wittgenstein to say what cannot be said…The task of philosophical reflection consists in unravelling this paradox.” (21). He writes elsewhere that “the whole point of philosophy” is to say what cannot be said 55). But trying to say what cannot be said is incoherent. There is no way of expressing the ineffable, whether dialectically by determinate negation, by way of mimesis, or by thinking in ‘constellations.’ It is equally misconceived to intimate that the non-identical is akin to bliss, happiness, or utopia, or to claim, as Adorno does in Negative Dialectics that “what cannot be subsumed under identity…is the ineffability of utopia” and then say that it is equivalent with “what Marx calls use value” (22). On such occasions, Adorno does not tiptoe round the paradox, but falls right into it. In “Adorno on the Ethical and the Ineffable,” I argued that it was, however, coherent and philosophically respectable to attempt to show what cannot be said, without saying it, and to interpret some of Adorno’s moves in Negative Dialectics as just such attempts. I made the same claim about negative theology and argued that this was the crucial analogy between Negative Dialectics and negative theology. Both yield a theoretical doctrine of radical epistemological modesty, and a practical ethics of human finitude. I took it that I had both explained how Adorno’s philosophy of non-identity forms the reverse side of his normative ethics of resistance and had provided the lineaments of a solution to the normative problem of Adorno’s ethical and critical theory.

My interpretation made a lot of assumptions, for example that there is a distinction between saying and showing, that there are ineffable insights, and that ineffable insights arise from being shown something that cannot be said, without disclosing in any way what it is an insight into. Whether what cannot be said, can be shown, is highly contentious. According to a well-known philosophical legend, Wittgenstein’s answer in the Tractatus is ‘Yes!’ While Frank Ramsey’s answer is ‘No!’. At least, that is the way in which Ramsey’s legendary quip “But what we can’t say we can’t say, and we can’t whistle it either” has been interpreted. If so, it would apply not only to Wittgenstein’s use of nonsensical propositions in the Tractatus, but also to the self-subverting dialectics in some negative theology and in Adorno. Because it has so many controversial premises, I’m not convinced nowadays by my conclusion that Adorno’s attempt to think the non-identical can serve as the normative basis of his ethics and critical theory.[3] Though I still stand by the claim that negative theology and negative dialectics are analogous in respect of their treatments of the paradox of the ineffable, and that the analogy, and the analogs, can be understood philosophically, without attributing any theological, religious, or Messianic dimension to Adorno’s thought.

And this is the crux of my disagreement with the second part of Gordon’s claim that negative theologians like Maimonides “pursue the via negativa to liberate us from idolatry and illusion such that we may arrive at a proper understanding of the divine.” Everything depends on what that means. If Gordon is referring to Maimonides’s cosmological argument for existence of God, I reply that this is not a negative theology, but rather a positive doctrine of theism, that Maimonides thinks (wrongly in my view) consistent with negative theology, insofar as it tells us nothing about what God is. Alternatively “a proper understanding of the divine” is that no human understanding of God is possible. In that case we agree, but what is at issue is “a proper understanding” of God’s transcendence and unknowability and of the limited and radically finite nature of human understanding. In which case, the difference is not that Adorno’s rigorously negative dialectic “dissolves the metaphysical object it was originally meant to serve” whereas negative theology illicitly reveals it. On my reading, negative theology is in the same boat in respect of the all too human aspiration to understand God, as negative dialectics is in its attempt to think non-identity by means of concepts.

How does all this help us interpret the theological motifs in Adorno? I think that Gershom Scholem went too far when he described Negative Dialectics as “one of the most remarkable documents of negative theology”. Mind you that remark occurs in a letter to Adorno, and Scholem was not above flattery, or enlisting others into his projects. Adorno’s guarded response is that he does not object to Scholem’s interpretation: “provided that this reading remains as esoteric as the subject itself.”83). I’m not sure what to make of that remark. It could be just a diplomatic way of saying: That’s what you think! Gordon’s reading of the theological motifs in Adorno in Migrants in the Profane suggests that he might take it more seriously than I do.

- He denies that they “can be stripped away as merely metaphorical husks for a purely secular philosophy” (138).

- He states, rather, that for Adorno, the “negation of religion fulfills its truth” (Gordon 2021a, 140), and that Adorno sees in modernity “the realization…of a religious truth he could not affirm.” (141).

- Finally, he allows that Adorno “appeals to theology” but “only to illustrate what our critical practice is like.” And that Adorno “found in religion, the critical energy” that his criticism of a damaged existence required (138, 142).

This interpretation is subtly different to Gordon’s earlier reading of what Adorno, in a letter to Walter Benjamin, once called his ‘inverse theology’. In Adorno and Existence, Gordon interprets Adorno’s inverse theology as a “counterfactual appeal” to transcendent standpoint that functions as a “limit concept.” (97). The earlier view implies that Adorno’s theological tropes are indeed merely metaphors. On that view, Gordon could still claim that the metaphorical appeal to the standpoint of theology was an illustration of critical theory, perhaps a precondition of it, but he’d not be able to claim as he does now, that Adorno “found in religion,” the standpoint that his criticism required. Adorno’s theology, Gordon now argues, is more than just a transcendental idea, since even though its religious content is negated, and not affirmed, it’s function is not only regulative. According to Gordon in Migrants in the Profane, “negative theology completes itself in negative dialectics” (140). The completion, or fulfillment of which Gordon speaks, is supposed to take place by determinate negation. I’m not sure that rescues the position. For “determinate negation” has a positive result, for all Adorno’s subtle attempts, he never shows how negation can be “determinate” and not have a positive result. If the negation is abstract, Adorno has no theology: if it is determinate it is not analogous to negative theology.

By contrast to Gordon’s most recent view, but closer I think to his earlier one, I hold that Adorno’s philosophy is “purely secular,” even though distinctions between secular and religious are not always clear cut. On this, I agree with the excellent – and sadly now departed – Adorno scholar, Deborah Cook. The wealth of biographical and historiographical material now available gives us no reason to think Adorno was anything but a secular humanist and atheist. And, as I’ve shown the analogy with negative theology can be understood entirely philosophically and does not warrant attributing any theological or religious dimension to Adorno’s work, not even one that is allegedly ‘fulfilled’ only ‘by negation,’ or realized, but ‘not affirmed.’ Adorno’s appeal to theology is, in my view, as he held Kafka’s theology to be, “feigned,” and a feigned theology is not one.[4] At best, Adorno adopts an “as if” theology, an attempt to cantilever a transcendent perspective which discloses this world as abject and in need of redemption. I even hesitate to claim that Adorno’s “as if” theology is a transcendental idea, in the sense that it is a necessary condition of critical theory. That’s because I don’t hold that Adorno has a unitary and coherent theory or practice of criticism. He has an ensemble of delicately but loosely interlocking criticisms and theoretical reflections on critical practice, which he attempts, sometimes successfully, to hold in tension. So, I’ll only go so far as to say that Adorno’s quasi theological motifs are among the most vivid and memorable images that he uses to reflect on his critical practice. To misquote Marx: If you don’t like the theological principles of Adorno’s critical theory, that’s ok. He has others.

[1] Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, 1958, 10-11. Basilides in Hyppolytus “Refutation of All Heresies” 7.20 = PG 166 3302C..

[2] Eckhart, Quint, 5b. Vol 1, Sermon 13, p. 106.

[3] Gordon also claims that his interpretation of Adorno’s theology answers the normative question (142).

[4] Adorno, Letter to Benjamin, December 17, 1934.

James Gordon Finlayson is Professor of Social and Political Philosophy and Director of the Center for Social and Political Thought at the University of Sussex. He has written many articles on German Philosophy and critical theory, and is currently working on a monograph about Adorno and transcendental homelessness.

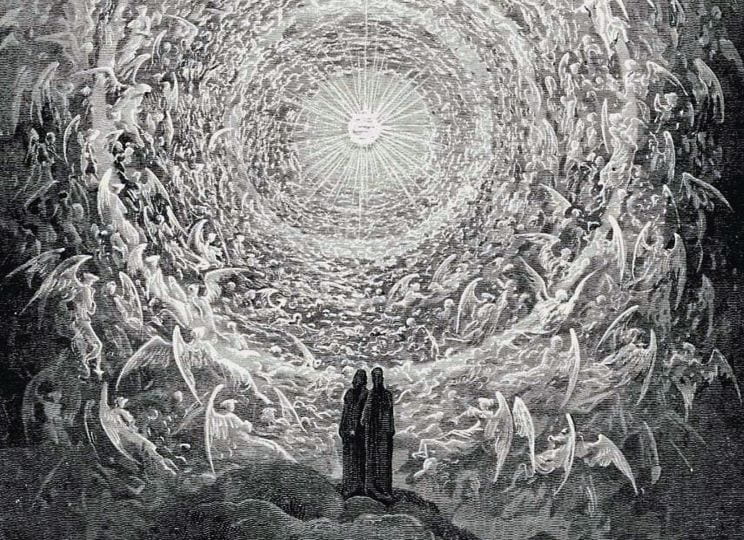

Featured Image: Gustave Doré, Paradiso, Canto 31. 1867. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.