Shuvatri Dasgupta

“But though ‘silver and gold he had none,’ he gave heart-service and love—works of far more value.”, wrote Elizabeth Gaskell about Jem Wilson (and John Barton), the working class hero(es) of her Victorian industrial novel Mary Barton. As I was re-reading Gaskell’s masterpiece, this particular sentence made me pause and wonder: what do we mean by valuable, or to put it in another way, how can we think of value as a concept, both historically and universally? What is the relationship between historical contexts and the processes of valuation in our lifeworlds? In this novel set in nineteenth century Manchester, torn apart by poverty, diseases, and death (resulting from industrial capitalism), Gaskell attempts to relocate value in affective unquantifiable categories such as love (and care), as opposed to commodities such as silver and gold, whose valuable status was already established by the material context of the narrative.

Historians of political economy as well as economic thought, have traced the genealogy of value either by locating it within markets which determine value, or through commodities, which function as material repositories of value. Taking a step back from this quantifiable understanding of the concept of value and the processes that determine it, Nancy Folbre in her work ‘The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems: An Intersectional Political Economy’, makes the case for broadening the category of ‘economic’ to include unquantifiable and undervalued aspects of life. In this wonderfully innovative work Folbre argues that all forms of hierarchy, whether it be of class, caste, race, gender, or ethnicity, are not only inegalitarian structures of exploitation by their very nature, but are economically consequential. The question of what is valuable (and in turn what is undervalued) can no longer be answered sufficiently through an exploration of either production and circulation of commodities or accumulation of profit. Instead we need a fuller picture where diverse hierarchies co-exist, and co-evolve, and co-exploit, and determine value through intersection and interaction with one another. In her earlier work ‘Greed, Lust, and Gender: A History of Economic Ideas’ Folbre had explored emotions such as greed, and lust, as unquantifiable expressions of desire and human self-interest. These affective registers not only shape ethical or moral frameworks of being, but act as central determinants of the actions of the homo economicus as a subject of capitalism, in Western political thought.

More generally, the figure of the homo economicus, or the ‘economic man’ in Foucault’s lectures on neoliberal governmentality, emerges as the atomised individual who valorises the pursuit of self-interest by becoming an entrepreneur, and emerging as the source of his own income by selling his labour. This subject of capital was therefore empowered through his ability to satisfy his needs in the market. Drawing on this Foucauldian genealogy, Ritu Birla in her book ‘Stages of Capital’ conducted a fascinating investigation of the capitalist subject in colonial India, and argued that the colonised homo economicus underwent a process of transition by bringing together vernacular market values (of kinship, family, caste, and community) and the logic of liberal colonial modern free trade in the British empire. Through this interaction, staged in colonial India, emerged the capitalist, fully formed and sovereign, now capable of self-government as an agent of capital accumulation, in postcolonial India.

Juxtaposing Folbre’s understanding of political economy, with that of the homo economicus, two deficiencies stand out rather starkly in the way the concept of value and related subjectivities are explored in the existing corpus of literature. Firstly, the question of gender remains largely unaddressed in the way histories of subjectivities (and their appropriation of value) are traced under capitalism. The role of patriarchy and other structural hierarchies in constructing, and transforming the homo economicus remains majorly overlooked. This has been addressed recently in some works, like Peter Fleming’s ‘The Death of the Homo Economicus’ and Emma Griffin’s ‘Breadwinner: An Intimate History of the Victorian Economy’. Secondly, there is an overwhelming focus on the more quantifiable aspects of the question, such as production, circulation, and accumulation, than on the more unquantifiable aspects of human life. Folbre argues in her construction of intersectional political economy that affect, and other aspects of social reproduction such as care, and domestic work, have longer pre-capitalist and non-capitalist histories of being undervalued. When we intend to explore historically why women’s labour related with care, reproduction, domesticity, and affect have been undervalued, we need to not only broaden the realm of political economy to include other hierarchies, but we also need to situate the household at the centre of such explorations, and bring the realm of the ‘economic’ back to the oikos.

Armed with this methodology, we can on one hand, revisualise the capitalist subject, beyond the construction of the economic man. It can emerge as it is, and as it always was: intersectional, produced by its context but also determining it, located at the liminal intersections of the home and the world, and inevitably suffering from the crisis of social reproduction which has been inherent in the workings of capitalism since its inception. On the other hand, we can broaden the remit of the concept of value, by exploring the unquantifiable aspects of life and the ways in which they became undervalued under the onslaught of capitalism, as Gaskell attempted to urge her readers to do, almost two centuries ago.

Tom Furse

Over July I’ve mostly been reading T.J. Clark’s The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848-1851 which is the first book of the two-part series about revolutionary politics in French art. It covers the short-lived Second French Republic (1848-1852) that existed between the July Monarchy and Napoleon III’s Third French Empire. The main painters in the book are Adolphe Leleux, Eugène Delacroix, Honore Daumier, Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Francois Millet, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Unfortunately, the illustrations (there’s a 109) aren’t in color, but Clark’s analysis brings them to life.

His writing style is quite polemical, but the analysis is never superficial. Probably the most famous painting of a revolution is Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Guiding the People, where Liberty, as represented by a semi-naked woman, leads well-dressed and tattered revolutionaries to victory over barricades. It is the image on Wikipedia’s entry for ‘revolution.’ Clark’s take on it is that we can see the bourgeois myth about its unity with the working-classes against a common royalist oppressor. If it was true, if the revolution really was universal and open to all, then the bourgeois would be entirely outnumbered by the masses. Of course, it was not universal. The National Guard defended bourgeois property and beat up the masses who got out of line. Delacroix painted Liberty in 1830, but its influence was pervasive in the book’s main years. To understand what Delacroix was painting and thinking about in 1848, we need to know this painting.

This fractious, somewhat mythical alliance between the bourgeois and working classes was a feature of how the Second Republic, as a state, thought about art. In 1848, the new government invited artists to compete for the visible representation of the new republic. There was a jury of politicians, artists and officials and the artists entered anonymously. The regulations and the bureaucracy of setting up this art commission went well. The trouble was that no one knew what they were looking for. What was this Republic? Artists like Ingres thought it was neither a dream nor a nightmare. Virginity was a common-ish theme among some entries, although Daumier and Millet didn’t go down that path. A letter from a minister to an anonymous artist said that their composition should unite Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, it should show stability and that the national colors (red, white and blue) should predominate. There 700 entries, and the jury recommended 500 of them seek other occupations. The event was a laughingstock. Clark argues that this event was an example of how the new state was a victim of its own utopian expectations and private fears that the Republic was actually visually, and therefore politically, ambiguous. It is little wonder that Napoleon III was able to electorally unite the peasants, the bourgeois and the military in his “18 Brumaire” coup in 1852.

A painting that stands out is Adolphe Leleux’s The Password, which is purposely undramatic with its two guards and a third wishing to pass through. It captures the everyday secrecy in periods of revolutionary fervour. From it we can imagine the scene: Travelling in the shaken city whose districts have turned to revolt becomes difficult; the streets and squares are littered with rubble and certain areas become out of bounds. The footsoldiers of the revolution stand guard across the city rooting out traitors and watching the hungry citizens. We see this in The Password where the two guards stand by a heap of stone bricks. The traveller, almost certainly fellow revolutionary, whispers the password in the ear of one as the other looks out. What is this the second guard looking at? There is no crowd or prying ears in the painting, and you don’t get the sense there is one either. The overwhelming sense from looking at this painting is that the street is entirely desolate; the tone is grey and dark and the feeling is of fear. The whispered password allows physical access, but it’s also a form of recognition at a time when people’s allegiances are fickle and masked: I know the secret word, just like you do, so we’re on the same side.

Oscar Broughton

In preparation for the 2022 Brazilian elections I have been reading Emir Sader and Ken Silverstein’s Without Fear of Being Happy. This introductory account of the growth of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (The Workers Party, PT) during the late twentieth century remains one of the most insightful English language sources on this subject. Although specialists in twentieth century Brazil will find little surprising in this account, it nevertheless proves to be an exciting and condensed account of PT’s early years. Taking its title from the hugely popular slogan adopted by PT, this work reflects on the growth of this political party since its formation in 1980 as it emerged out of the increasing violence and social inequality under Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-1985) and was forged by a diverse group of activists, trade unionists, landless peasants, and progressive members of the Catholic Church. Out of this mixture emerges a history of the development of the Brazilian working-class and PT’s most recognisable leader, Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva, the former factory worker turned politician. Lula remains a dominant figure in Brazil today and is currently tipped to win the 2022 elections, so this book provides useful insight into his early career.

However, perhaps most interestingly, is the analysis of the left-wing ideology at the core of PT. Despite being openly “socialist” the ideology of PT defies easy categorisation and shares little connection with the earlier anarchist and communist movements in Brazil, or international socialist groups during the mid twentieth century. As a result the development of PT highlights the shifting character of social democracy towards the end of the Cold War, which serves as an interesting case in comparison to other left-wing parties undergoing changes during this period in Latin America and Europe especially.

Originally published in 1991 this book misses much of the most recent dramatic history of PT. In particular, this book does not give an account of the electoral successes of PT beginning with Lula’s first victory in 2002 and the introduction of highly effective and popular social welfare programs, such as Bolsa Família, and the massive expansion of higher education leading to the creation of large numbers of new universities. Furthermore it does not include an account of PT’s descent into crisis in 2013 following nationwide protests against price increases in public transport and corruption scandals, which precipitated the 2016 impeachment of the then PT president, Dilma Rousseff. Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings this account provides a detailed and useful account for historians interested in the contemporary history of Brazil and formative preparation for next year’s elections.

Grant Wong

“What do I do the summer before I start graduate school?,” I asked a trusted mentor. “Do something fun, travel, spend time with friends,” she replied. “Read whatever you want, you’ll have plenty of time to labor over academic work in the Fall. Take a break if you can, it’s been a difficult year.”

This exchange is what eventually led me to Neil Strauss’ The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society of Pickup Artists (2005). Part-memoir, part-reportage, the book follows Strauss’ misadventures in the pickup community, an Internet-linked, international group of men dedicated to the pursuit of “picking up” women – that is, talking with them, going on dates, and orchestrating one-night stands. It is a masculine world, dominated by self-styled “PUAs” (“pickup artists”) who teach fresh faced “AFCs” (“average frustrated chumps”) socialization skills, self-improvement, and, in their view, the most effective means of appealing to the opposite sex – mastering a mental and social “game.” Strauss himself becomes a pickup artist in the process as his PUA alter-ego “Style.”

The book details a series of episodes defined by toxic masculinity, positive male bonding, blatant misogyny, and at the very end, an ambiguous rejection of pickup culture for its failure to teach its community the importance of genuine romantic connection. Whether expressed through techniques like “the neg” (diminishing a woman’s self-esteem as a means of provoking interest), “peacocking” (wearing attention-grabbing clothes), or assessing when to “kino” (using physical touch to build rapport), pickup culture resides in a highly gendered, performative world. Pickup techniques appear to be effective due to the self-confidence they instill in their practitioners (one study does note the effectiveness of some of pickup’s basic principles), though they verge into uncomfortable ethical territory when the logic of “the game” is taken too far. Once the women they are meant to appeal to are imagined not as people but solely as “HBs” (“hot babes”) and puzzles to be mastered, “the game” becomes morally bankrupt.

This appears to be the general lesson of the book, though I find The Game to be much more revealing when considered in its wider contexts – the twentieth and twenty-first-century transformations of masculinity, capitalism, and communication technologies shed much insight into the mental frameworks of pickup artistry. As vapid as it might appear at first glance, it does have a distinctive intellectual worldview, shaped by these changing historical trends. Pickup even has a history in its own right, dating back to the original publication of Eric Weber’s How to Pick Up Girls! (1970), though Weber, interviewed in The Game, rejects modern pickup culture on the basis of its denigration of women.

As depicted in The Game, masculinity within the pickup community is shaped by performance and mindset, whether it be the “Mystery Method” or “Speed Seduction,” as masterminded by PUAs “Mystery” and “Ross Jefferies,” respectively. Many PUAs developed their teachings from their own experiences of social awkwardness, and thus knowingly demonstrate their masculinity through carefully-calculated charisma. Conventional attractiveness and athleticism are more often associated by PUAs to “AMOGs” (“alpha males of the group”), who are to be socially bested as a Revenge of the Nerds-style matter of principle. The performance of masculinity, through “sarging,” (going out to meet women) serves both as a means of group bonding and discord. The PUAs of The Game build each other up in their successes, but tear each other down when they view their masculinities as threatened.

Capitalism is also an ever-present theme throughout The Game. PUAs are obsessed with the concept of “value,” broadly defined. The dating world is viewed by them as a sexual marketplace, as women are commodified, rated on scales of one to ten based on their attractiveness. Male attractiveness, too, is determined by a market-based mindset – to “DHV,” or “demonstrate higher value,” is to showcase one’s worth to a woman in a social setting. Another summer read, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild’s The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times (2012), offers similar takes on the commodification of romance. Interviewing a dating coach, Hochschild finds that some of the coach’s clients have so internalized their romantic lives in capitalist terms that they put less investment into dating. They perpetually seek to “trade up,” imagining themselves in a “buyer’s market.” I was reminded by this upon learning about the PUA concept of a “pivot,” a woman brought along on a PUA’s shoulder for the sole purpose of attracting more desirable women. Much actual capital is spent over the course of the book as well. Over the course of The Game, PUAs “Papa” and “Tyler Durden” found and operate a lucrative pickup school, Real Social Dynamics. By the end of the book’s narrative, PUA Mystery charges $2,250 a head for each of his Las Vegas pickup workshops.

Lastly, it’s important to note the importance of technology to the pickup scene, which would be unrecognizable without the connections made possible by the Internet. Through online forums, most prominently “Mystery’s Lounge,” PUAs share their experiences online via “field reports,” discuss pickup theory, and organize workshops across North America, Europe, and Australia. In essence, they form their own twenty-first century republic of letters as they philosophize over the effectiveness of different pickup approaches and critique their community. In one notable forum post, Strauss accuses his fellow PUAs of becoming “social robots,” too set in their routines to showcase their genuine personalities to women.

All in all, The Game was a thought-provoking read, if only for forcing me to ask myself, “how did we get here? What historical trends have led us to reshape masculinity around a commodified ‘game,’ to view dating as a market, to create digital communities of mutual support and knowledge-sharing?” In any case, The Game has reignited my academic interests in sexuality, gender, and capitalism. Perhaps not the kind of summer reading my mentor envisioned.

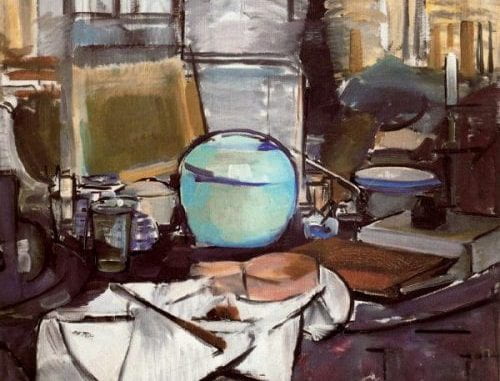

Featured Image: Still Life with Gingerpot 1, Piet Mondrian, 1911. Gemeentemuseum den Haag, Hague, Netherlands.