By Ismael Medkouri

A house of many names

The house-type known in architectural jargon as habitat marocain is the most ubiquitous feature of the contemporary Moroccan landscape.

Commonly this house-type is simply called dar, colloquial for ‘house’, with no qualifiers necessary. It is the other types of houses that require categorical precision: the apartment (bertma), the detached house (villa), and the medina-house (dar beldiya). The latter house-names are meaningful idioms in Moroccan society: the apartment connotes liveliness and modernity; the villa speaks of status and wealth; the medina-house represents the historically authentic lifestyle. But the common dar constitutes, as Le Corbusier famously identified the modern house, straightforwardly une machine-à-habiter – a machine-for-dwelling. A case in point: the common house also casually goes by the technical appellation of R+2, for rez-de-chaussée-plus-deux-étages (street-floor-plus-two-levels). It denotes the concrete aspects of its utility. The R+2 is a construction comprised of a commercial-use street-floor, and two additional habitable levels where domestic life takes place.

***

In academia and architectural research, the R+2 has been either dismissed as a “simplistic construction[s] without particular meaning” (‘constructions simplistes et sans signification particulière’) or all together neglected (p. 158). Studies have instead focused on more glamourous subjects: the medieval medinas of Fez or Marrakech; the outlandish kasbahs of the Atlas Mountains; modernist architecture through the colonial era; and the so-called bidonvilles (literally: canister-towns, i.e. shantytowns).

For the state, the R+2 has been a contrivance in the decades-long fight to eradicate the bidonvilles. In the administration, the house-type is more readily known as habitat économique (‘affordable housing’), and is considered to be of mediocre quality. It was only ever meant as a provisional accommodation for a marginal class of society, and not as a primary component in the state’s vision for the Moroccan city. Instead, they promoted the ‘modern’ (read: European) forms of the apartment building and the detached house for the average household. If today two-thirds of Moroccans live in an R+2, there is a sense, as one journalist put it, that they only do so for lack of a better alternative.

***

In spite of public policy, it is the R+2 that has been determining, in practice, the morphology of the Moroccan city – and that of settlements in the countryside as well. It makes up some of the most vibrant neighborhoods of Casablanca, Tangiers or Marrakech, on which strictly residential neighborhoods made of apartments and villas are utterly dependent. The mixed-use layout of the R+2 hosts a full spectrum of businesses and services, from car mechanics to dentists, interspersed with an overabundance of grocers and coffee shops.

The looseness of regulations and the possibility of vertical expansion creates housing and business spaces of varied layouts, dimensions, and tenures. In contrast to the sober appearance of apartment buildings, the R+2’s single-façade has evolved into an eclectic medium of cultural expression (a phenomenon vocally deemed “ugly” by cultured society). In the countryside, they sprawl along driveways and emerge sporadically within historic hamlets, housing multinuclear families, servicing locals in bazaar items and travelers with an embarrassing array of barbecue joints.

***

The common house of Morocco was called many names, and ascribed contradictory origins. Ben Ali or Aït Hamza speak of the R+2 as an essentially “urban” type, which only later colonized the countryside. But Eduardo Bernasconi has called it “l’habitat semi-rural” (semi-rural house), and argues that its origins lie in a rural mode of dwelling that spread to the city via rural exodus. Benelkhadir and Lahbabi coined the catchy style “habitat de l’émigrant” (house of the emigrant), because the house-type is funded and supposedly determined by the remittance economy. In turn, Hein de Haas argues that the house-type rather materializes the social needs of locals who, in the absence of welfare, seek the financial security of the R+2 which offers hereditary shelter, a storefront, and the potential of a partial rent out.

A synthesis of the palimpsest of meanings associated with the R+2, the National Housing Survey of 2012 formally identified the house-type as “la maison marocaine moderne”, or the Modern Moroccan House. The name avows the prevalence of the house-type in today’s national landscape. It also asserts the longstanding idea that the MMM is the successor of the analogously named “maison marocaine traditionelle” – the Traditional Moroccan House. This genealogy goes back to the concept of ‘habitat marocain’, which emerged during the French colonial administration of Morocco (1912-1956) to distinguish the native mode of dwelling from modern (i.e. European) architecture.

Across the entangled histories of governmentality, knowledge, and spatial practice in 20th century Morocco, habitat marocain has evolved into an amalgam of form, law, and idea that is seen today as a natural object of the Moroccan landscape. A history of this familiar object demands a disentanglement of (1) the idea of what a characteristically Moroccan dwelling is, (2) the artifacts, made and inhabited by people, that are collectively categorized as Moroccan Houses, and (3) the contingent legislation that formally regulates the construction of Modern Moroccan Houses since 1964.

Conceptualizing habitat marocain

The concept of habitat marocain, or the idea that there exists a distinctively Moroccan sort of dwelling, crystallized at the turn of French colonial rule in Morocco (1912-56),under the tenure of modernist architect Michel Écochard as head of the protectorate’s Services d’urbanisme from 1946 to 1952.

Before, ‘habitat marocain’ simply referred to wherever natives lived. The category was interchangeable with less specified terms such as quartier indigène (‘native neighborhood’), maisons arabes (‘Arab houses’), or médina (literally ‘city’ in colloquial, referring to the native walled city). Practically, ‘habitat marocain’ served not to emphasize a belonging to a Moroccan essence, but only to differentiate native quarters from colonial quarters.

When Écochard and his international team of architects – Georges Candillis, Alexis Josic, Shadrach Woods, and Vladimir Bodinsky – took on the unprecedented task of housing the native proletariat, they began by methodically conceptualizing what it meant for an habitat to be marocain. As they saw it, their task went beyond providing adequate shelter. Their task was also to carry out the project of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM): reinvent the modalities of housing for the industrial age. They called themselves the Group of Modern Moroccan Architects (GAMMA), and their deliberate aim was to define the Moroccan house of the future.

GAMMA’s prototypes achieved global fame at the CIAM conference in 1953, where Candillis notably championed the iconoclastic idea of ‘vernacular modernism’. Contrary to the universalist dogma of the founders of CIAM (e.g. Le Corbusier), this new generation of modernists advocated the inclusion of local cultural practices in the design process. The pilot projects of Candillis, Woods, and Studer showcased this new creed by reproducing the inward-looking courtyard house of Moroccan tradition in the modern form of high-rise apartment buildings through the clever use of cantilevers, overlapping slabs, and outdoor passageways. In their fame, they gave international visibility to the concept of habitat marocain. The housing projects they built reified the supposedly essential characteristics of The Moroccan House: a gender-segregated layout, blind facades, and the courtyard.

Moroccan-ness and historiography

In their search for a Moroccan Modern, Écochard and GAMMA relied on a knowledge of native house-forms that was, and arguably still is, contingent on the colonial situation.

First, in western knowledge, Morocco belongs within the category of the Middle East and North Africa – a politically corrected substitute for the Orient. But in history, Morocco has been at the Far-West (al-maghrib al-aqsa) of the Muslim World, politically and culturally estranged from its centers. In terms of material culture, Morocco has shared more across its longitude, between Senegal and Iberia. The continuous, and occasionally massive movement of kings, courtiers, merchants, craftsmen, slaves, captives, and ordinary people across the strait of Gibraltar have kept architectural know-how on par.

Because of its late colonization, Morocco was perceived by Western scholars to have escaped modern alterations, and thus to have been paradoxically one of the best-preserved specimens of the historically “Islamic City”. This reification of cities in Morocco cast them as conceptually estranged from western urbanism, when historically this was not the case.

In trying to identify what stood for ‘Moroccan’, the French historiography of North Africa notably privileged the medieval period. Initially an artifact of the archive, this bias was compounded by politics. French administrators chose to emphasize the non-Arab history of Morocco as a way to legitimize colonial rule. The emic category of al-barbar, which in Arabic was a contingent attribute, was reinvented as a racial category under which the varied ethnicities that did not speak Arabic were subsumed. These berbères were identified as the original inhabitants of North Africa, a proto-European people disenfranchised by Arab invaders. This definition made the Berbers a natural ally of Western civilization against all things ‘Arab’.

Monuments of the so-called Berber dynasties were restored, advertised, and emulated in the ornamentation of modern buildings – while the arabophone dynasties that succeeded them were flouted. Notably, King Hassan II (1961-99) perpetuated this image in his monumental projects of public architecture, such as the Mausolée Mohammed V (1961-71) in Rabat and the Grande Mosquée Hassan II (1986-93) in Casablanca, both built in the distinctive style of the Almohad dynasty (1121-1269). This historiographical and archeological selection had enduring repercussions on what counted as ‘Moroccan’.

Finally, the colonial efforts to maintain the material culture of Morocco was associated with the need to monetize it through tourism. Regulatory policies canonized ‘traditional’ architecture and strongly limited the ability of natives to add to or modify their environment to accommodate new needs and practices. Native forms of urbanity, such as the Medina, became fixed attractions: they could not change in external form nor extend beyond their existing walls. But the rapidly changing demographics of the Medina, which lost its elite and gained a disproportionate number of migrant workers, necessarily altered the internal morphology of the house, as well as the institutions that governed urbanity. Still, the houses of the Medina continued to be the primary reference for the ‘traditional’ Moroccan House.

***

Coming into law: the afterlife of habitat marocain

The house-type today known as habitat marocain is not, in actuality, based on GAMMA’s prototypes.

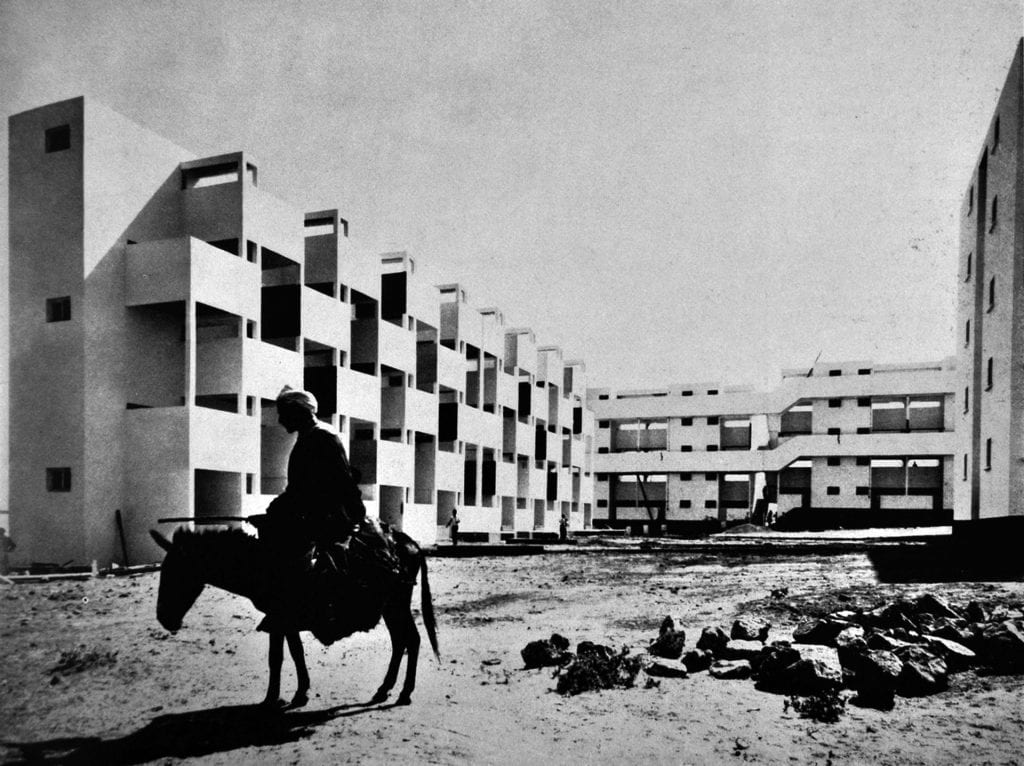

To temporarily quell the housing shortage of the 1950s, Écochard had conceived a basic cell of 8×8 meters, consisting of two (gendered) rooms, a water closet, set around a courtyard “in the oriental fashion” (“à la mode orientale”) (p. 16). The cells were densely imbricated for a minimal street layout, in what became known in architectural history as the trame Écochard. The vision was for this trame to be shortly replaced with the high-rise models being tested by GAMMA. Instead, the 8×8 cells became permanent. They quickly grew vertically as emigrant families grew into multinuclear households, and the inherent density prompted businesses to take over the ground floor.

As the urban population of Morocco soared in the 1950s, the versatile morphology that resulted from these reappropriations became an archetype for massive informal subdivisions. And by the 1960s, the scale of the phenomenon was such that the newly independent authorities were prompted to integrate the proliferating house-type into its legal compendium. Hence the infamous Dahir of 26-12-1964, which codified the Modern Moroccan House.

The rest is history; but one that has yet to be written. What knowledge –and whose– defined Moroccan-ness as we know it today? Whose practice gave form to the common dar that characterizes the contemporary Moroccan landscape? Within what legal traditions, and according to what rationalities was the MMM codified as a formal house-type?

***

Note: all translations not otherwise attributed are courtesy of the author.

Ismael Medkouri is a Ph.D Candidate in History at Princeton University. Ismael was trained as an architect in Montpellier (France) and Rabat (Morocco), and holds an MS in Geography from the University of Montana. His research interests revolve around the reproduction of space in the western Mediterranean.

Featured Image: Houses in Ain Médiouna, Province of Taounate. Taken on 7/23/2019. Courtesy of the author.