By Caitlin Cawley

“I was born three days after 9/11,” begins Zendaya’s Rue Bennett, the Gen-Z heroine of HBO’s Euphoria (2019), “My mother and father spent two days in the hospital, holding me under the soft glow of the television, watching those towers fall over and over again until the feelings of grief gave way to numbness.” When Euphoria premiered, I watched Zendaya identify the “numbness” gripping post-9/11 America and was reminded of my owninitiation into the age of “forever war” and “permanent conflict.” It was March 21, 2003. My sisters and I were gathered around the television in the basement of our childhood home watching the news: CNN was broadcasting live footage of the “Shock and Awe” bombing of Baghdad. My youngest sister, Alicia, had turned ten a week earlier. Being almost six years older than Alicia, I took great pride in telling her about history and current events, in explaining the world to her as best I could.

She looked at me, baffled, “What’s happening? Why are we bombing them, Caiti? Are people going to die? What is this?” I turned to my other sister. Kristen was only twelve, but as a voracious reader and astute learner, she was my trusted confidant in such matters. But Kristen did not budge—she just kept staring at the television screen, watching the smoke and fire overtake the cityscape and desert and listening intently to the sound of missiles, explosions, alarms, and, occasionally, silence.

“I don’t know,” I conceded. So the three of us stood there without words and watched.

In the days, months, and years since March 21, 2003, the United States has waged cataclysmic military campaigns across the Middle East, and American civilians have displayed unprecedented indifference toward America’s wars. The public’s indifference or numbness is especially glaring given the nation’s history of antiwar activism. By the late 1960s, more Americans identified as peace “doves” than as war “hawks” (over 50% by some estimates). Civilians and soldiers were taking to the streets in staggering numbers to support the largest antiwar movement in US history. On October 15, 1969, for example, the nationwide Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam drew between two and five million Americans into public protest. In comparison, the largest Iraq War protest, which took place on February 15, 2003 in New York City, drew between 200,000 and 375,000 people. Of course, the late 1960s is an exceptional period in terms of mass mobilizations—but so is the twenty-first century. Four of the five largest political demonstrations in American history took place between 2016 and 2020, which tells us that the public’s ambivalence toward the brutal and costly campaigns in South Asia and the Middle East is not the consequence of a growing sense of political indifference or civic disengagement.

This phenomenon has preoccupied a wide range of thinkers, yet scholarship on why these protracted, bloody wars have mostly escaped public scrutiny and activist interventions is far from complete. To summarize, historians and political scientists argue the civilian-military divide, the natural outgrowth of an all-volunteer force as well as an increasingly isolated and privatized military sector, gives the average American civilian little reason or opportunity to appreciate these conflicts. Psychologists and sociologists point to common human responses to distant wars and atrocities, including compassion fatigue and psychic numbing, while other experts hold the mass media and federal government responsible for failing to give the public sufficient and accurate information about these campaigns.

Cultural theorists and philosophers have understood this issue as inseparable from our dominant representations and signifying practices. Political action and the boundaries of political life, Judith Butler and others argue, are predicated on our ability to recognize subjects as such. The life of an Afghan boy must be intelligible as a life, it has to conform to certain conceptions about what life is, in order to be recognized, valued, grieved, and “lost.” According to Butler, the dominant U.S. media has made it easy for American civilians to deny the existence of contemporary warfare’s human victims:

[I]t is only by challenging the dominant media that certain kinds of lives may become visible or knowable in their precariousness. It is not only or exclusively the visual apprehension of a life that forms a necessary precondition for an understanding of the precariousness of life. Another life is taken in through all the senses, if it is taken in at all. The tacit interpretive scheme that divides worthy from unworthy lives works fundamentally through the senses, differentiating the cries we can hear from those we cannot, the sights we can see from those we cannot, and likewise at the level of touch and even smell.

(Frames of War, 51-52)

In other words, the media frames through which Americans apprehend the wars in the Middle East and Global South support a racist Western imaginary wherein non-Western lives are non-lives.

Other critical theorists have focused on representations of “terrorism” since the 1980s, when the Reagan administration declared war on “the evil scourge of terrorism.” In his study of the iconology of the so-called War on Terror, W.J.T. Mitchell shows how the terrorist is “the unimaginable standing in as the absent signified, the thing that cannot even be conjured up in fantasy as a mental image or concept, what cannot be remembered” (60). Faceless, headless, anonymous, and reduced to “bare life,” the Western figure of the terrorist is an absolute and unthinkable enemy, always already outside political action and the boundaries of political life. Jasbir Puar, Perveen Ali, and other legal scholars have echoed this sentiment. For many Americans, Iraq is an illegible space populated by illegible bodies because the justifications for the invasion and occupation of Iraq were never legally tenable and the US-led coalition forces operated outside international humanitarian laws. For example, many of the Iraqis detained between 2003-2014 were never classified as enemy combatants, creating a population of “un-legal” or legally unrecognizable subjects. Similarly, occupied Iraqi civilians were refused the rights of sovereign subjects, denied state protections, and forced to endure brutal human rights violations.

These explanations provide a fragmented picture of our permanent war state in part because they do not address the nature of contemporary warfare. Over the last thirty years, the concept and practice of occupation—which for the US armed forces dates back to the occupations of Nicaragua (1912-1933) and Haiti (1915-1935)—has evolved from a fringe mode of military operations to the dominant form of warfare. While there is a growing body of scholarship on occupation, we are just beginning to answer key questions about the shift in war making: What tactics, conditions, and strategic logics distinguish occupation-style warfare? How does the nature of occupation impact civilian attitudes toward war? Why does this style of military engagement emerge as a response to the Vietnam War and the anti-Vietnam movement? And how does it contribute to the status of armed conflict in post-9/11 America, where war abroad is seen as a permanent yet inapprehensible part of the political and cultural landscape?

Films and literary works about the US-led campaigns in the Global South are rich sources for unpacking why today’s wars seem to exist beyond the American public’s affective, intellectual, and political grasp. Most simply, these forms are deeply invested in the project of apprehension. More specifically, the war genre is uniquely engaged with the evolution of its primary subject: war. One could argue that military history has had a greater hand in shaping the genre than the history of cinema or literature, and numerous critics have, including the novelist and essayist Wilfrid Sheed. In his review of David Halberstam’s Vietnam novel One Very Hot Day (1968), Sheed begins, “Every war dictates its own literary tactics, its rhetoric and scale of operations. Romantic or bitter, panorama or keyhole—each war works up its own style and breeds poets to order.” Thus, readers who “don’t like” Halberstam’s Vietnam fiction “can always blame it on the war.” Sheed’s argument is an extreme iteration of a materialist perspective, but this kind of determinism is reinforced in a host of more complex and nuanced ways. We see it in the pressure artists, critics, and the wider public have voiced for “authentic” and “true” representations of “real” war. We see it in the way each generation’s war narratives, taken as a whole, are such exceptional barometers of a conflict’s political, historical, and military legacy. And we see it in the preponderance of soldier-poets, of individuals who claim they were made writers and artists by their war experience.

My own research focuses on the subgenres and innovations that characterize today’s war genre. As part of my current book project, I have been indexing and analyzing a wide range of contemporary works that fall under the war-genre umbrella, from “grunt’s-eye-view” documentaries by American filmmakers to surrealist conflict-zone narratives by Arabic writers. This work redirects critical attention from the subjects that dominate contemporary war studies, namely terrorism and the news media, toward the subject of occupation. Moreover, it brings two new insights into relief. First, the phenomenon of occupation structures this emergent creative body. Second, occupation-style militarism generates resolutely ambivalent and incoherent visions of war.

Critics have acknowledged that narrative irresolution and anticlimaxes are trademarks of war stories about Iraq. This trend is understood as a symptom of different conditions: inexperienced writers and filmmakers; writers and filmmakers who are more interested in philosophical questions than historical ones; virtualizing technologies; global terrorism; late capitalism; the list goes on. This trend, however, is inseparable from occupation-style warfare. To conclude, as both an introduction and invitation to a new direction in war studies, I’ll offer an example from Phil Klay’s award-winning collection Redeployment (2014).

Redeployment reflects one of the many ways occupation-style militarism structures today’s war genre. Klay, who served in Iraq’s Anbar Province from January 2007 to February 2008,

dedicates an entire short story to a young veteran trying, again and again, to tell a war story about his deployment in Iraq, and he can’t. And he can’t because he did not fight in a war; he occupied “over there.” Unlike soldiering in major twentieth-century wars, occupying Iraq lacks a coherent objective or telos and a genuine enemy or other. “I didn’t know what I wanted to tell her,” the young Marine thinks after he describes watching an Iraqi boy’s “heat fading out” through a thermal scope, the first of his “failed” attempts to tell his Amherst classmate a true story about his service (194). His description is anticlimactic precisely because he does not recognize the moment as a conflict or active encounter. The practice of occupying hinges on the strategic logics of repetition, permanence, asymmetry, and randomness, which situate occupiedpeople and spaces outside the conceptual frameworks that support a narrative structure and, more broadly, intelligibility. In other words, the job of an occupier, Redeployment suggests, is to violently subjugate occupied people and affirm nothing is happening. The occupation of Iraq requires American soldiers to disavow the possibility of an encounter, climax, and new trajectory. In turn, for occupiers, occupation is emphatically a non-story.

The ending of Klay’s fictional veteran-civilian dialogue is, unsurprisingly, unresolved. The sense of authority, clarity, and connection initially displayed by the narrator and his female classmate gives way to a sense of ambivalence, confusion, and detachment: “Maybe we’ll talk another time,’ she said. Then she gave a slight wave of her hand, turned, and walked back to campus” (212).Like heat fading out, the story ends there, and readers are left asking, what just happened? This response is part and parcel of occupation-style militarism, and continuing this dialogue—that is, continuing to interrogate the complex numbness and complex violences brought about by America’s occupying military—is one way scholars can intervene in our state of forever war.

Caitlin Cawley is a Lecturer at Fordham University in New York City, where she teaches courses in film studies, American literature, and critical theory. Caitlin is currently working on a book project titled “Occupying War: American War Culture since 1989.” For more on her scholarship, check out www.caitlinmcawley.com.

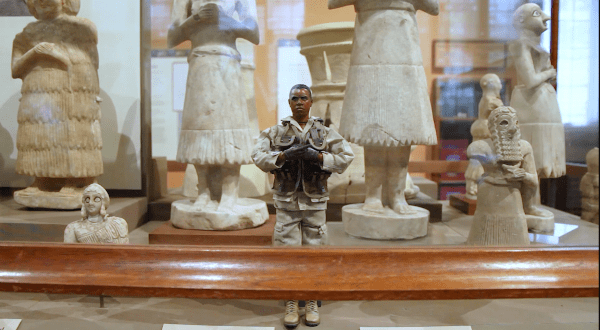

Featured Image: Michael Rakowitz, The Ballad of Special Ops Cody, 2017, Stop-motion video. Courtesy of Michael Rakowitz.