By Matthew Firth

There is an anachronistic element to looking for “queens” in early medieval Europe, and perhaps particularly so in the West Saxon kingdom of the ninth and tenth centuries. Precisely what makes a queen a queen varies between places and over time. As Janet Nelson identifies, in contrast to male categories of power in early medieval Europe “it is much harder to identify anything that could be called queenship” (p. 39). Historians have, nonetheless, adopted certain sub-categories of queenship based around a royal woman’s means of accessing authority that have broad application. As summarized by Theresa Earenfight, these are queen-regnant, queen-regent, queen-consort, queen-mother or dowager-queen (p. 6). Only one of these constitutes authority in its own right, the queen regnant. Queens-regnant, however, are not a feature of the political landscape of tenth-century England. Queenly agency was rather defined and delimited by each woman’s relationship with the king, the starting point of which was usually as queen-consort.

West Saxon queens rarely enjoyed ceremonial investiture of power nor recognized claim to formal title. The marriage of the Carolingian Princess Judith to the West Saxon King Æthelwulf (839–58) in 856 was cast as an extraordinary event by various medieval commentators because, at the ceremony at the royal palace at Verberie in Francia, she did not merely marry the reigning king of Wessex but was also consecrated as his queen. The Frankish cleric, Prudentius of Troyes, declared that, for Æthelwulf, this was “something not customary before then to him or his people” (p. 83). In recounting the event, Asser, the biographer of Alfred the Great (871–99), adds further detail, stating that “the West Saxons did not allow the queen to sit beside the king, nor indeed did they allow her to be called ‘queen’, but rather ‘king’s wife’” (p. 71). Asser perceives this to be a “perverse and detestable custom”, founded on the exemplar of the early tenth-century queen-consort Eadburh who was purported to have abused her queenly authority and ultimately to have poisoned her husband the king. Whatever truth may lie behind Asser’s tale, his observations of West Saxon attitudes to queenship seem to have a certain veracity. After Judith’s consecration, which in itself was informed by her status as a scion of the West Frankish royal family, no English queen is known to have again been anointed as such until over a century later in 973.

The matter of West Saxon attitudes toward queenship as an ‘office’ is particularly pertinent to the idea of queenship in England more widely in the tenth century. Alfred’s reign in the late ninth century marked a turning point in the fortunes of Wessex and the West Saxon royal family. The Viking incursions of the ninth century saw the decline and failure of most of England’s other kingdoms and royal families. Following Alfred’s successful defense of Wessex, he began a process of expanding West Saxon hegemony, while his descendants would go on the become the sole rulers of a reconstituted English kingdom. And the political milieu of the tenth century would bring several powerful women to the fore, whose authority would seemingly bely any exhortation against the dangers of female power. Yet it also remains that despite any personal agency, such women are only rarely named as queen.

The most famous of these powerful tenth-century women is, perhaps, Æthelflæd of Mercia. The conclusion that queenly authority derived from proximity to kingship here remains unavoidable, despite Æthelflæd’s remarkable personal agency. She was the daughter of King Alfred, sister to his successor King Edward the Elder (899–924), and wife to Ealdorman Æthelred, the proxy king in Mercia. Æthelred’s own authority was exercised under the overlordship of the West Saxon kings. Æthelflæd’s was an extraordinary position. Alongside her connections to West Saxon royalty, she was an heir of the Mercian royal house by matrilineal descent. For Æthelred, his marriage to Æthelflæd in the 880s did not then just cement a Mercian-West Saxon alliance, but brought additional legitimacy to his rule. This in turn granted Æthelflæd a remarkable degree of authority to the extent that, following Æthelred’s death in 911, she continued as sole ruler of Mercia until her own death in 918, albeit in partnership with her brother. Critically, however, Æthelflæd is largely ignored in West Saxon histories, while the Mercian evidence never calls her queen, but Myrcna hlæfdige or domina Merciorum[Lady of the Mercians]. This would, seemingly, be a legacy of the West Saxon reservation of bestowing queenship. As Pauline Stafford identifies, Welsh and Irish sources show little reservation in identifying Æthelflæd as queen.

There is, however, no evidence that Æthelflæd was anointed as a queen or given formal title. Indeed, while formal marriage can be assumed between Æthelred and Æthelflæd, there is no clear evidence for such ceremony either. And in a society where queens were rarely anointed, the status that came from being the legitimate wife of a king could be foundational to queenship. As Stafford argues, marriage raised women to queenly authority in the absence of consecration (pp. 127–9). At a fundamental level, what would now be identified as queenship was, in tenth-century England, predicated on marriage to the king. As a result, the distinction between a king’s wife and a king’s concubine was politically charged.

Many of England’s tenth-century kings have been characterized as serial monogamists, most notable among these being Edward the Elder and Edgar the Peaceful (959–75) who both had three consorts. In such cases, the blurred line between concubine and wife may have been intentional. A lack of formal marriage allowed the setting aside of one concubine in favor of a more politically attractive union relatively simpler. If there was no evidence of marriage, no public declaration of intent, no exchange of lands, then how simple for a king to set aside consort as a bed companion alone with no marital legitimacy. This was, no doubt, the approach taken by both Edward and Edgar to their unions with their first wives; it is no coincidence that it was most often a king’s first consort, a match made before he ascended the throne, who was identified as a concubine.

The difference in status could have political and ideological ramifications for a consort’s children and her legacy, especially where a queen-consort survived her husband, thus transitioning into roles as queen-mother or dowager-queen. In these cases, her continued authority rested on an ability to demonstrate the legitimacy of her union with the king. This was especially important where more than one consort had a son with the king. Whatever agency consorts were able to establish for themselves within male-dominated political spheres, the primary expectation of queens-consort was to produce heirs, legitimatesons. Thus, proving the legitimacy of a marriage could also serve to establish the primacy of a son as heir. For this reason, some of England’s most powerful tenth-century queens reached the apex of their authority as queen-mother. This is certainly the case for Edward and Edgar’s thirds consorts, respectively named Eadgifu and Ælfthryth.

There is no evidence of Eadgifu being crowned queen-consort (though David Pratt makes as case for it). She was also likely quite young at the time of Edward’s death and thus their sons would only have been children. Her stepson Æthelstan succeeded to the crowns of Wessex and Mercia in 924, and Eadgifu disappears from the historical record. However, she returns to power with her sons Edmund and Eadred. While she never claims the title queen, at least in contemporary records, she clearly takes up a position of power and regularly witnesses charters in a prominent position, subscribing as mater regis [mother of the king] over fifty times. Eadgifu’s fortunes vary during the reigns of her grandsons, but she does live long enough to witness a charter alongside Ælfthryth in 966. Here Eadgifu witnesses as aua regis [grandmother of the king], while Ælfthryth witnesses before her as legitima prefati regis coniuncx [legitimate wife of the aforementioned king]. This witnessing demarcates a new phase of queenship in England, one that has developed over the preceding century more slowly than this brief article has been able to outline and to which Eadgifu was integral. What is important here is that Ælfthryth’s clear delineation as legitimate wife, made very shortly after the birth of their first son, is an unambiguous declaration by Edgar of his third consort’s pre-eminence and the primacy of their son as heir.

Ælfthryth’s queenship was legitimated as no queen-consort’s had been since Judith’s coronation. She was a regular witness to Edgar’s charters, attesting as regina[queen] around twenty times, the first West Saxon consort to do so. She was a known intermediary with the king, at times receiving gifts for performing in that role. She was a landholder – the queen’s dower having increasingly become a traditional prerogative through the tenth century. She was codified in Regularis concordia as patron and protector of the kingdom’s female religious houses. Finally, she was formally crowned queen in 973 alongside her husband during the pageantry of his second coronation in Bath. Ælfthryth’s tenure as queen was remarkable for the shift toward institutional office that codification of duties and consecration implied – the latter an exemplar for her successors with coronation becoming the norm in the eleventh century.

Yet while this is an important moment in the evolution of early English queenship, it does exist on a continuum with earlier ideas around female power and queenly legitimacy. Edgar’s various methods of legitimising Ælfthryth and her children could not insulate her from dynastic unrest connected with the legitimacy the children of his earlier consorts could also call upon. Upon Edgar’s death in 975, factions formed around his surviving sons, with that backing Ælfthryth’s stepson Edward (975–78) attaining control of the throne. I have addressed the bloody end to Edward “the Martyr’s” reign and its impact on Ælfthryth’s legacy elsewhere. In the immediate term, however, upon Edward’s death in 978 Ælfthryth’s young son Æthelred II (978–1014/16) came to the throne, his mother by his side. Like Eadgifu before her, Ælfthryth took up a prominent role in her son’s court, witnessing as mater regis no fewer than sixteen times. But more than this, as Levi Roach identifies, Ælfthryth appears to have seized regency powers along with her closest allies in the early years of Æthelred’s reign (pp. 85–6). Thus, a century on from Asser’s cautions around the dangers of queenly power, a consecrated queen stood at the head of English government as mother and regent.

Ælfthryth’s regency is a good place to leave this overview of West Saxon ideas and ideals of queenship in from the late-ninth to late-tenth centuries. The agency of English queens had shifted dramatically from the time when Asser declared king’s wives could not claim that title, to Ælfthryth’s explicit use of the title regina and claiming of regency authority in the name of her young son. Nonetheless, there remains a certain truth to Asser’s assessment of West Saxon queenship even as it developed the trappings of institutional office as the tenth century progressed. Tenth-century English queenship remained fundamentally connected to a woman’s relationship to the king. To borrow Stafford’s words in closing, “queenship is thus no more or less than the crown on the head of wife and mother, at most the formalization of their roles.”

Matthew Firth is a PhD Candidate in the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at Flinders University, South Australia. His published works have appeared in The Court Historian, Royal Studies Journal and International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, among other venues, and focus on England’s pre-Conquest kings and queens and their legacies. He has a particular interest in how royal reputation was transmitted, adapted, and memorialised in the histories of later medieval writers. Matthew is currently writing a book for the Routledge Lives of Royal Women series, entitled Early English Queenship, 850–1000: Potestas Reginae. Matthew is also assistant editor for the Brepols series, East Central Europe.

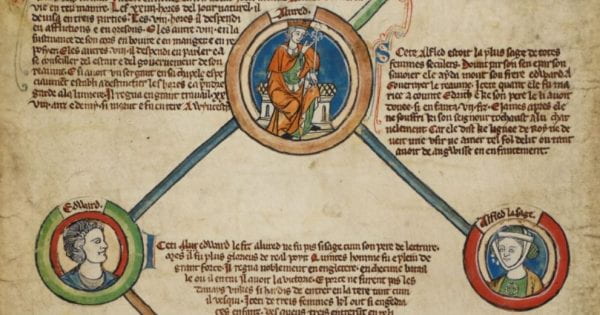

Featured Image: King Alfred the Great, King Edward the Elder, Æthelflæd Lady of the Mercians © British Library Board, Royal MS 14 B VI

1 Pingback