By Egas Moniz Bandeira and Caio Henrique Dias Duarte

In 1907, diplomats from all over the world gathered in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in The Hague, for the Second Hague Peace Conference. Among the first truly global diplomatic conferences, the event became a stage for an unusual transcultural encounter. The Brazilian delegate, Ruy Barbosa (1849–1923), a fierce defender of the principle of sovereign equality of nations, was the main protagonist in opposing a proposal by the US and the European powers to create an international arbitral tribunal with themselves as permanent arbiters. In his closing speech, he deplored that Europe only recognized the US in its political horizon, ignoring Latin America and Asia. Japan’s military victory in 1905, however, had secured the latter a place amongst the Great Powers, and Barbosa stressed that Brazil wished to accomplish the same by diplomatic means before it felt compelled to enter into the arms race itself. The Chinese ambassador, Lu Zhengxiang (1871–1949), subsequently wrote an euphoric report back home in which he adapted Barbosa’s speech to fit his country’s situation. In view of the importance of military power in international relations, he urged his government to “amass military prowess” and to carry out constitutional reforms (in the broadest sense) in order to “shut up all countries.”[1] Whereas Ruy Barbosa saw the military path for ascension as a last resort that he hoped to avoid through diplomacy, Lu took his speech as an exhortation of a bellicose stance, which China should pursue as well.

Such encounters are still barely accounted for in the current Eurocentric epistemologies of Empire. As Robert Marks points out, Eurocentrism sees “Europe as being the only active shaper of world history, its ‘fountainhead’ if you will. Europe acts; the rest of the world responds. Europe has ‘agency’; the rest of the world is passive. Europe makes history; the rest of the world has none until it is brought into contact with Europe. Europe is the center; the rest of the world is its periphery. Europeans alone are capable of initiating change or modernization; the rest of the world is not.” Since the end of the twentieth century, historians have called for the provincialization of Europe to counter this premise. In spite of their divergences, numerous historiographical approaches—ranging from comparative and transnational history, world history, big history, and global history to postcolonial studies and the history of globalization—agree in their objective of coming to terms with the connectivities of the past by moving beyond Europe.

Much has to be done, however, for this goal of showing a truly global circulation of ideas, from their theoretical construction in debates to its political and institutional applications, to actually be achieved. In March 2021, Oxford University Press published its two-volume Oxford World History of Empire, a massive handbook edited by Peter Fibiger Bang, Christopher Bayly, and Walter Scheidel. An ambitious enterprise, the Oxford World History of Empire enlisted contributors of the highest caliber to create a non-Eurocentric world history and show that “against the backdrop of world history, European colonial powers emerge unexpectedly as an especially unstable form of imperialism.” This followed an earlier volume by Routledge under the moniker History of Western Empires, which also brought refreshing approaches to the circulation of ideas. Despite the many relevant contributions in these and other handbooks, however, we should be paying attention to what is missing rather than what is present. Non-European Empires are often overlooked in such analyses; they are seen as either receptacles of a vertical transit of ideas or not seen at all. The Routledge volume, for example, still lacks a counterpart on Eastern or even African and Native American Empires, and in Oxford’s World History of Empire, the absence of case studies on the Empire of Brazil or the Empire of Japan, for example, raises questions about how much of the world is actually covered in this “non-Eurocentric world history.”

For a truly in-depth analysis of how knowledge was and is built, a shift in perspective is necessary: rather than adopting the view of the central lighthouse that sheds light onto whatever it sees as it revolves, we ought to be looking into what happens in the shadows. Recent efforts such as that of Antonio Manuel Hespanha, who sought to understand how local networks of power in the Portuguese Empire consolidated its rule overseas, are noteworthy in this regard. With a historiographical focus on how such epistemologies emerged through the interaction between shadow locations, we may discover important actors and developments that evade the momentaneous glimpse of the center.

+++

In Brazil’s case, we can detect intense interaction and knowledge-building in the shadows of colonial and imperial times. During the colonial period, the same borders that were debated in the palaces of Europe were to be constantly redrafted through intense disputes between local actors who took into consideration cultural factors deemed of little importance in the official diplomatic negotiations. Similarly, the Empire crafted its own tradition of equality of rights and of legal treatment between nations—isonomy as a principle of International Law—in its border disputes after the disruption caused by the Paraguay War (1864-1870). As the separate peace treaties signed with Paraguay shows, Brazil disagreed with its former allies on how to treat the defeated nation: while Argentina intended to annex a fair share of Paraguayan territory, Brazil defended the country’s territorial integrity. In the following years, surrounded by intense political disputes in the republics born out of Spanish America, the Empire and the Republic which succeeded it sought arbitration rather than war to solve the recurring border disputes. Whether their contestants were Great Powers such as the United Kingdom or smaller nations, such as Peru, Brazilian diplomacy drew from the cartographical knowledge amassed by the Portuguese diplomatic tradition, favoring the exclusivity of legal means to solve those disputes. This very same idea was brought to the Hague in 1907 by Ruy Barbosa and, from there, to China by Lu Zhengxiang.

Pedro II, whose reign spanned almost the entire duration of the Brazilian Empire, was a frequent traveler and an avid scholar. His participation in the 1876 Congress of Orientalists during a trip to Saint Petersburg is a testimony to the fact that such networks existed. Just as his Empire’s diplomats—most of them legal scholars—worked on crafting legal strategies to defend its interests, so did Russia: in its wars against non-European states and nations such as the Ottoman Empire, the Romanov Tsars combined a consolidation of war customs with the organization of international conferences to codify international law. Saint Petersburg (1868), Brussels (1874), and even the First Hague Convention (1899) were convened at the initiative of the Romanovs. Sadly, the interaction between the two Empires is still under-researched, although connections abound. The only substantial production is on the subject of the scientific expedition (1824-1829) by Baron Langsdorff during the reign of Pedro I in Brazil.

While Latin America was trying to assert its presence in the international community through the “peaceful door,” as Ruy Barbosa put it, Japan entered it by way of the “war door” when it militarily defeated Russia in 1904/05. In the Oxford History of Empire handbook, Japanese history is only addressed in one chapter, where it is combined with the German experience in a context of “great power competition and the world wars.” Much beyond this comparison with its ally in the Second World War, though, Japan would merit a central place in any exploration of nineteenth- and twentieth century Empire that aspires to be “global.”

In 1905, Japan’s victory in what has been termed “World War Zero” not only sent political shockwaves throughout the world but also established Japan as an alternative model of imperial modernization on equal footing with the Euro-American imperial powers. While the Japanese state was pursuing aggressive policies of colonial and imperial expansion, such as the annexation of Korea under Resident-General Terauchi Masatake, the country’s vertiginous rise did not fail to exert considerable attraction to intellectuals struggling with their own countries’ existential crises, such as reformist thinker Liang Qichao in the Qing Empire and even the foreign minister of the Ethiopian Empire.

Indeed, Japan came to inform political reforms far beyond its close vicinity. In Lu Zhengxiang’s ailing Qing Empire, the Meiji reform served as the main, although not exclusive, blueprint for the constitutional reforms undertaken from 1906 onward. Beyond East Asia, the Japanese model was widely discussed in Siam and the Ottoman Empire, among others. The pinnacle of Japan’s trajectory as a global model of alternative modernization was reached in the early 1930s, when Ethiopian intellectuals and politicians identified the imitation of Japan as the secret to becoming a strong and powerful nation. In late 1931, a diplomatic delegation led by foreign minister Həruy Wäldä-Selasse embarked on a journey to Japan, where the party visited factories, offices, farms, zoos, theatres, railways, shrines, museums, and military training schools. Upon their return, Wäldä-Selasse published a book titled Mahdärä Bərhan Hägär Japan (The Place of Light: The Country of Japan). The Ethiopian Constitution, promulgated the same year, drew heavily from Japan’s 1889 constitution, thus becoming a legal testament to imperial encounters beyond the Euro-Atlantic circuit.

Rather than just offering an erudite exploration of the intellectual connections of such Empires, these seemingly unusual events can point us in a new direction of studies and discussions and cause us to revisit concepts while trying to understand how such Empires and their populations, institutions, and traditions interacted.

One field that has greatly benefited from this approach is the study of the history of slavery. Recent research has focused on the interaction between slaveholding elites, but also on how slave communities interacted among themselves through the Atlantic networks, consolidating identities, with researchers trying to understand the practices of resistance and, later, of abolitionist ideas and political action.

If we are to look at communities of practice and epistemic communities that work and interact in the shadows of our traditional gaze, we bring a series of challenges to standardized assumptions about Empire, such as that of essentialized identities frequently present in historical narratives. When defining the scope of historical analysis, such challenges are not a matter of discarding legal categories, political institutions or even cultural manifestations because of their geographical origin, but rather of trying to draw an enlarged map of the debates that constructed knowledge and dictated practices—thinking in networks rather than in categories.

[1] Lu Zhengxiang 陸徵祥, Juzou Baohehui qianhou shizai qingxing deng zhepian qing daidi you 具奏保和會前後實在情形等摺片請代遞由 [Memorial about the actual circumstances before and after the Peace Conference, &c.; with a request to retransmit], Guangxu 34/01/16 [February 17, 1908], file no. 02-21-004-01-003, Archives of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taipei, [11].

Egas Moniz Bandeira holds a Ph.D. from the University of Tohoku (Japan) and is currently a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in Frankfurt (Germany). His main research interest is global intellectual history with a focus on its refractions in modern East Asia. He is co-editor of the volume Planting Parliaments in Eurasia, 1850–1950: Concepts, Practices, and Mythologies (Routledge 2021).

Caio Henrique Dias Duarte is an MA student at the University of São Paulo (Brazil). He is coordinator of Amigos do Itamaraty, a cultural preservation initiative of the Diplomatic Museum and Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Brazil. His research focus is on Russian and Brazilian foreign policies and legal and diplomatic practices during the 19th century.

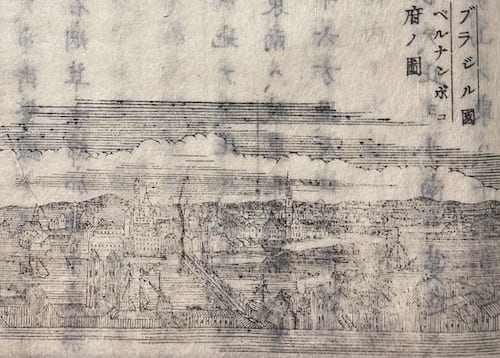

Featured Image: A drawing of Recife, a relevant coastal town, that accompanied a description of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s Imperial capital, in a Meiji-era geography textbook. Shihan gakkō 師範學校. Bankoku chishi ryaku 萬國地誌略 [Sketch of world geography], 3 vols. (Tokyo: Monbushō, 1874), 3:29. Picture taken by the authors.