By Anderson Hagler

To what extent can historians understand spiritual belief among the people of the past? What do references to magic tell us about colonial life? In Mexico, the Inquisition operated from the early sixteenth century until 1820. It viewed vernacular belief and attempts to use magic as existential threats to Christianity and potentially heretical. Inquisitors and their scribes recorded proceedings, documenting every word spoken by accused heretics. Because the threat of torture produced droves of confessions, the truth value assigned to coerced testimony remains problematic for historians. It is safe to conclude that many of those charged with crimes against the faith framed their actions in the best possible light, hiding incriminating pieces of evidence as they could.

In this essay, I suggest that historians should shift their analytical focus away from the personal faith of the declarant to evidence of shared knowledge evincing communal belief in the supernatural. Examining the exertions of the devout in the material world reveals how eighteenth-century Indigenous commoners attempted to restore spiritual equilibrium by using magical rituals to heal the infirm. The testimony analyzed herein illuminates belief in tonalli, the soul or vital force believed responsible for human life.

Historians of European witchcraft such as Jan Machielsen maintain that belief ranges from cautious acceptance to a perceived matter of fact. The Indigenous peoples of colonial Mexico often linked their terrestrial experiences to cosmological knowledge, transforming belief in the supernatural into a broadly accepted cultural lexicon. Catarina Pizzigoni’s examination of Indigenous wills and testaments in Toluca Valley has shown that Nahua peoples linked the physical structure of their homes to local saints and deities. In Pizzigoni’s account, sincere religious devotion played an important role in Nahua communities and households. Lisa Sousa has analyzed criminal records in Oaxaca to investigate belief in magic and witchcraft. Building on their findings, this essay employs Inquisition records to analyze agrarian folk beliefs, extrapolating complex cosmologies and hierarchies of belief from statements made by Indigenous people to the Inquisition.

On April 20 1721, an eighteen-year-old Indigenous man named Agustín Díaz, alongside a local leader from the pueblo of Ocelocalco named Nicolás Fabián, testified that Agustín’s brother Sebastián had fallen ill after suffering an accident in the mountains. Agustín recounted that Sebastián had fallen while inspecting a beehive. A severe injury to Sebastián’s leg had caused the tonalli to escape from his body. Without tonalli, Sebastián became sick. Later that evening, Sebastián fell from a bench while sleeping, a worrying display of spiritual disequilibrium. Nicolás Fabián explained that the fear generated by severe accidents created disease inside the body.[1] Extended loss of tonalli would prove fatal, a prospect which frightened the men.

Tonalli hemorrhaged from the body after someone suffered a great fall or became very frightened—occurrences common among children but less routine for adults. The proper response was to pray to restore tonalli and to visit a spiritual practitioner. In Chiapas, according to Nicolás, women practitioners preserved and consulted cures for all manner of illnesses, including loss of tonalli. References to tonalli in Sebastián’s case and others like it reveal the limits of the Catholic Church’s reach in rural Indigenous areas and the extent of local belief in the supernatural.

In Soconusco, devotees first tried to restore tonalli by lighting a candle and praying to Mary, Mother of God. Agustín treated Sebastían by incensing the room and keeping him tightly wrapped. After three or four days with little result, Agustín returned to the mountains, desperate to increase the efficacy of these rituals. He located the exact spot where Sebastián’s accident took place. At the spot, Agustín put some of Sebastián’s clothes inside a jar and sealed it. He called Sebastián’s name several times. Once home, Agustín collected some dirt and a moth. He ground them together and gave the product to Sebastián to eat. Afterwards, Agustín incensed the room, causing Sebastián to sweat profusely. Sebastián recovered, validating medical knowledge and perpetuating belief in tonalli and the metaphysical system of which it was a part.

In these eyes of Catholic clergy, these ceremonies were an offense to God and the saints. God became angry when Natives incorporated Catholic prayers and relics into non-orthodox rituals. But the Indigenous peoples of Soconusco felt that they had employed these cures successfully for too long to abandon them. Petrona González, the mother of the leader Nicolás Fabián, had once used a similar cure to restore her tonalli. According to testimony, Indigenous commoners testified that they practiced these rituals because of the love they felt for ailing family and friends, not out of malice toward God or the Church. The physical lengths to which Agustín resorted to heal his brother demonstrate how desperation could produce recourse to popular belief. The rituals conducted to heal Sebastián reveal a complex cosmology and catalogue of ceremonies preserved by Indigenous elders. Although we cannot know whether Agustín believed that the vernacular ceremony was certain to heal Sebastián, we can conclude that Agustín did not believe that the ceremony could harm his brother.

From Agustín’s labor we can extrapolate the extent of his belief in tonalli. The testimony states that Agustín incensed the room and wrapped his brother “anxiously” (con ansias) for “three or four days” before returning to the mountains where Sebastián suffered the accident next to the beehive.[2] Journeying to the mountains with Sebastián’s clothes, calling out his name, returning home, collecting earth nearby, and grinding dirt with a moth were time-consuming activities which could have been spent on basic functions. The energy exerted by Agustín implies sincere belief in the tonalli ritual. The ways in which he and other witneses refer to the ritual imply that the existence and function of tonalli was considered to be common knowledge in his community. The spiritual-medical advice of Indigenous elders reinforced Agustín’s belief in the supernatural, while successful enactment of their knowledge was considered to be proof of their authority.

Because villages like Ocelocalco exercised significant local autonomy throughout the colonial era, non-orthodox beliefs persisted. Historians can read between the lines in order to understand the hierarchy of values and beliefs of Indigenous witnesses and defendants, taking vernacular knowledge as much as possible on its own terms. This is made difficult by the fact that such testimonies are mediated by Catholic officials, and furthermore by the fact that indigenous testimony is often filtered through what Indigenous declarants imagined to be Catholic orthodoxy. Nonetheless, trying to understand the beliefs and cosmologies behind the behavior of the actors in the trial can help us understand the motivations which led Indigenous commoners to behave contrary to orthodoxy, despite the palpable danger of doing so. Foregrounding behavior and emotive testimony in this way can help us understand Indigenous belief in eighteenth-century Mexico.

[1] AHDC, Folder 2463, exp. 1, Soconusco III A1, Episcopal, Gobierno, 1721, fol. 8v.

[2] The emotive testimony may plausibly be taken at face value as there is no reason to suspect that Agustín had quarreled with Sebastián. AHDC, Folder 2463, exp. 1, Soconusco III A1, Episcopal, Gobierno, 1721, fol. 8r.

Anderson Hagler is a PhD candidate at Duke University. His scholarship examines how subaltern vassals negotiated state-led attempts to impose orthodoxy. His most recent project analyzes how magic and deviant sexuality intersected with one another, shaping notions of race and class during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in New Spain.

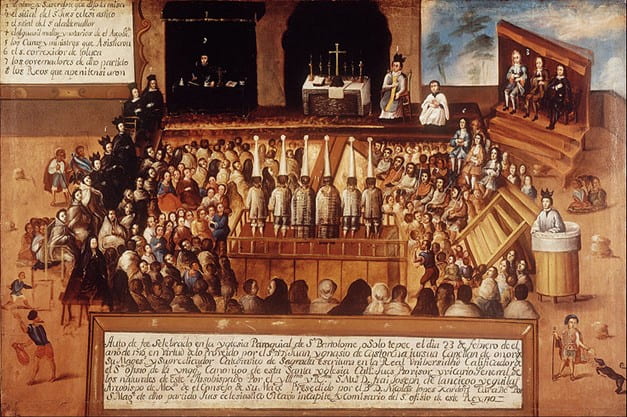

Featured Image: An auto da fe in the town of San Bartolomé Otzolotepec, 1716. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.