Tom Furse

Over the last month, I’ve been reading David Edgerton’s The Rise and Fall of the British Nation: A Twentieth-Century History. Rarely can we be convinced of something at once, but for me, this book (with some qualifiers) did it. It made me look at my own country in a new way. This book pushes against Thomas Nairn, Peter Cain and Tony Hopkins’ story of British history as one of a slow decline managed by a stodgy Edwardian ruling class. His revisionist account is that after the Second World War, Britain, as a nation, began to exist. Pre-1945 Britain was not a nation because it couldn’t be divorced from its empire, which incidentally, it didn’t trade with that much in comparison to Europe and US. The 1956 Suez intervention was a national war (with France and Israel), not an imperial war. It was only when it became a nation that it started relying on Australia, New Zealand, and others and then, in 1973, it joined the Common Market for good or ill. The book is built from an analysis of British capitalism, state militarism and political-economic ideas. It is on ideas where Edgerton is fascinating, how the Tory Party nearly mainstreamed protectionism or his contextualizing of Edwardian free trade ideas as particular to that time, and so can’t be reborn despite how contemporary free-trade advocates might try. The book gives us a detailed picture of a nation that was post-imperial, with protected industries, and thought in strictly national terms—British Rail, British Leyland, and the National Health Service.

Jonathon Catlin

Martin Jay’s latest book, Genesis and Validity: The Theory and Practice of Intellectual History, is forthcoming in the University of Pennsylvania Press’s series Intellectual History of the Modern Age. This collection of mostly previously published essays (see links) centers around the age-old problem of genesis and validity, the extent to which the meaning of ideas is bound to the historical contexts in which they were created, reevaluated against the contemporary backdrops of multiculturalism, the provincialization of Europe, and “this day and age of identity politics” and “speaking azza.” A thorough introduction explores the problem from various angles, while Jay articulates his own nuanced position in essays on how “events” produce new ideas and a related skepticism toward David Armitage’s call for transhistorical studies of “big ideas”. Reflections on the ironic affinities of presentist Hayden White and contextualist Quentin Skinner and a communitarian conception of historical truth forge a path out of the reductive binary of relativistic historicism versus universalizing transcendentalism toward a third possibility inspired by Frank Ankersmit’s notion of “sublime historical experience”: “the importance of opening ourselves to the radical alterity of a past that resists being ‘appreciated’ or judged by present values, and in fact my fruitfully challenge them.” Jay thus calls for “a mutual relativization of contexts”: contexts of genesis but also contexts of reception; of the past but also of present historians’ narcissistic claims to superior understanding. Essays on Blumenberg, Lukács, and Benjamin and Berlin model Jay’s famous “synoptic” style of intellectual history, which balances the transcendent validity claims of “philosophy” with the subject-positioning of “theory,” the Habermasian impulse for “rational reconstruction” with the Benjaminian and Adornian impulses to present ideas in unstable and reflexive “constellations” and “force fields.” Ultimately, Jay concludes, “we come to history to be torn out of the complacency of the present.”

Shuvatri Dasgupta

On the centenary of Rabindranath Tagore’s Visvabharati University, established with the agenda of decolonising the educational curriculum in colonial India, it seems apt to ask: How can we conceptualise a decolonised classroom on a planet heaving under an unprecedented advent of capitalism and increasing climate crisis? Priyamvada Gopal’s recent article provides some key indications on the project of decolonising the university, where she argues that metropolitan universities can begin the task by taking a cue from anti-colonial ideas and institutions. Drawing upon the works of Kenyan-Marxist thinkers like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Gopal makes the crucial and compelling argument that institutions in the erstwhile colonial metropole must grapple with their violent histories, and estimate the material and affective costs of their past, to begin the humongous and reparative task of decolonising. Tagore’s vision of an anti-colonial educational project which he developed over the course of his lifetime, can also be a source of inspiration. Visvabharati University, formalised back in 1921, relied largely on biophilic practices of education such as open air classrooms, celebrating seasons, and commemorating the annual ritual of tree plantation. Tagore sought to refocus the teleology of India’s educational infrastructure in the early twentieth century, from being valued and estimated in terms of grades, degrees, and jobs, to largely undervalued ethico-moral parameters such as generosity, kindness, mutual interdependence, and collective thinking. He reimagined the pursuit of knowledge as a pursuit of truth, as an end in itself, rather than as means to an end. After all, education must aid in remaking our worlds for the better, and decolonising pedagogy, within an anti-capitalist, pro-environmentalist framework, remains crucial for that.

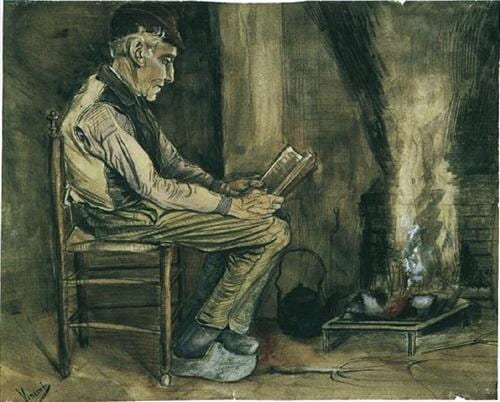

Featured Image: “Farmer sitting at the fireside and reading,” Vincent van Gogh, 1881. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands. Courtesy of WikiArt.