By Lotta Vuorio

In 2018, while working on my Master’s thesis, I ran into a peculiar anecdote in a Victorian health manual called The Prevention and Cure of Many Chronic Diseases by Movements. Written and published by physician Mathias Roth in 1851, the manual concerned ways to apply physical activities for curing diseases, a method that was also known as “movement-cure” at the time. The anecdote that caught my attention, rather than a fully fleshed out story, was actually just a mere one sentence hidden within the instructional text. Curiously reading through the manual’s appendix listing various diseases that had been cured with movement-cure—or at least claimed to have been—I scanned the list alphabetically: abortus, after-pains, apoplexy, apparent death, bleeding from the nose, and then there it was. Under the title cancer, it read:

A lady who suffered from a malignant cancer on the breast, was cured by a little dog frequently sucking her nipple.

I had already moved on from cancer to cold and cough when I abruptly turned back and glanced at the description once again. A malignant cancer on the breast? A nipple-sucking little dog? How on earth were these related to each other, or to movement-cure, in any way?

As I was reading the manual 170 years after its initial publication, this one-sentence story seemed irrelevant and bizarre at first. Yet upon closer inspection, I realized that it revealed a broader logic of health, the body, and physical education that was likely anything but odd to the cancer-stricken woman and her contemporaries. Indeed, I argue in the following, this anecdote illustrates the need for reconsidering the meaning of “movement” and moving one’s body in the historical context of physical education and physiology of mid-nineteenth-century Britain.

The British discourse on health and education took off in the 1850s and continued throughout the following decades among physicians, physical educators, and social reformists. Historian Gertrud Pfister has been very clear about the bottom line for discussing physical education and health in nineteenth-century Britain and Europe more generally by drawing attention to several major developments, such as the Enlightenment and the faith in science, that were connected to the rising demand to better understand the human body. As historian Tiina Kinnunen reminds us, this interest in understanding bodily functions was also connected to knowledge about shaping one’s body. In the context of physical education, the human body was not merely considered a godly creation that was untouchable and pre-determined. Instead, its shape and composition could be transformed by means of diet and exercise, for example. More broadly, physical education was understood to be based on scientific facts that would contribute not only to “the harmonious development of body and mind” but also to British nation-building. Sociologist Herbert Spencer, for example, noted “the relationship between the evolution of the race and of the individual,” which was subsequently used as an argument for developing national physical education. The goal was to educate citizens to follow a healthy lifestyle so that they could perform their duties as British citizens. Hence, the making of the individual healthy body was deemed crucial in producing a healthy and thriving British nation.

Although physical education was a middle-class ideology, it aimed at controlling the health of the entire British population and was thus designed for intersectionally diverse groups—including women, children, the blind, the “deaf and dumb,” and the working class. It also reflected concerns about race in its goal to prevent the supposed and feared degeneration of the British nation, caused by industrialization and urbanization. While the primary focus in physical education was on the metropole, it also appeared in the context of Empire, where it served as “a site for constructing their authority, legitimacy and control” and contributed to “making colonialism an embodied experience,” as Sudipa Topdar has argued. Similar debates over the role of physical education in developing the racial body occurred in other European countries, including France.

Within this context of physical education, scientific “movement-cure” aimed at curing specific diseases and unhealthy conditions, like the woman’s breast cancer I happened upon in the health manual by physician Mathias Roth. As Roth himself pointed out, movement-cure belonged in the toolbox of physical education. Indeed, it could help combat what Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had identified as the “deteriorating physique of the people,” which in consequence would cause “the history of England [to] soon be the history of the past.”

Yet, even though medicine was not stringently organized as a profession at the time, Roth certainly did not represent the mainstream of British medical practices in the mid-nineteenth century. Born in Hungary, Roth moved to England in 1849 and began to strongly advocate for the exercising doctrines of Swedish physical educator Pehr Ling (1776–1839) long before Ling’s doctrines became popular in the 1870s and 1880s. The Prevention and Cure of Many Chronic Diseases by Movements (1851) was his first health manual that introduced Ling’s doctrines to a British audience, and he published at least five other books addressing physical education or movement-cure as a scientific method for curing diseases: Movements of Exercises for the Development of Human Body (1852), The Gymnastic Free Exercises of P. H. Ling (1855), Hand-book of the Movement Cure (1856), The Prevention of Spinal Deformities (1861), and On the Neglect of Physical Education (1879). The 1851 manual, like the ones that would follow it, was geared toward medical professionals—such as physicians, surgeons, and orthopedists—who might find the practice of movement-cure useful as a supportive tool alongside their medical practices.

But what was movement-cure then, exactly? According to Roth, it was a medical methodology based on Ling’s doctrines of medical gymnastics, and it was meant for curing or alleviating diseases with scientifically proven methods. The movement-cure process began with identifying the disease, and then prescribing a set of movements or physical exercises targeting at selected body part or bodily function that needed to be cured. As Roth explained, “the effect of a movement is the result of its action and the reaction of our organism.” In other words, moving one’s body was understood to have an organic or physiological effect that would transform unhealthy body functions into healthy ones. The health manual itself relied heavily on exemplary cases in its argumentation, wherein patients’ maladies were cured through carefully selected movements. The examples were often accompanied by a story line where no other method could have cured the case. For example, while sharing the movement-based prescription for curing asthma, Roth asserted: “This patient, after having consulted for a number of years several physicians, and having been treated without any success, resolved finally to take his last resource in the treatment by movements.” The prescription for this patient included rubbings of the loins from the spine forwards, rotating the patient’s feet, and lengthwise “chopping” or tapping of the back. The fundamental idea behind movement-cure was not novel in the nineteenth century, as Roth reminded the reader, but rested on the originality of its scientific method. In order to address the historical background of this method, Roth decided to place an appendix at the end of the manual that consisted of a long list of cases in which many a diseased condition had been cured with treatment by movements.

It was here, in the section of historical cases, that I came across the woman “who suffered from a malignant cancer (and) was cured by a little dog frequently sucking her nipple.” The manual does not specify why the movement-cure was performed by a little dog, but evidently the occurring movement and its healing affect caused the case to be included in the historical appendix and to be retrospectively considered a movement-cure. One can ponder whether the intimacy, warmth, or the relationship between the lady and the dog were decisive for the process. Having a dog as a pet was increasingly popular in Victorian Britain, especially among the middle class as a way to emphasize class distinction. It is also known that throughout nineteenth century, cancer was partly conceived of as a product of the civilized lifestyle, which would explain the connection between the dog and the presumably middle-class woman and her breast cancer. And yet, we cannot truly know the exact relationship between the woman and the dog, especially because the case functioned as a historical example of movement-cure.

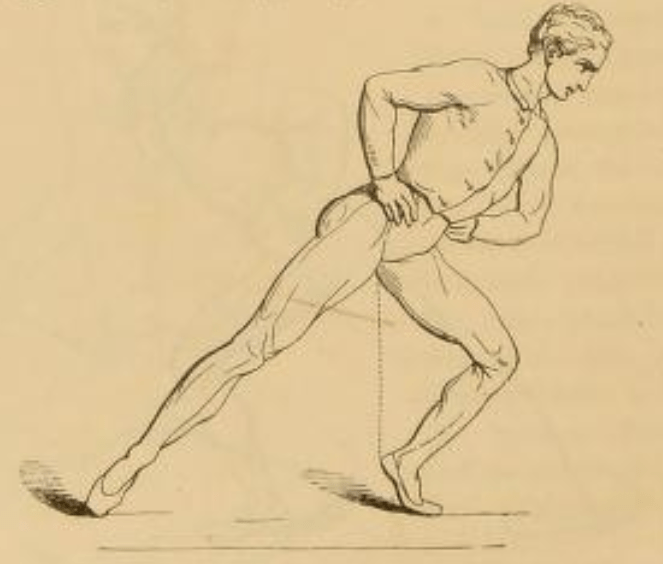

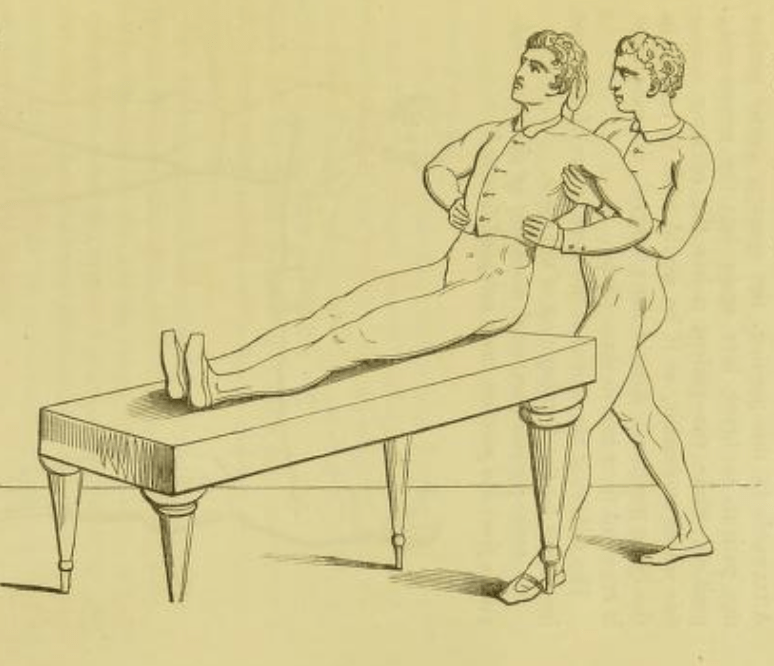

What we do know, however, are the grounds for movement-cure. In medical gymnastics and movement-cure, movements were divided into three categories: active, passive, and combined movements. Thus, “moving” one’s body could be achieved in several ways. The body or its parts could be moved independently either by a patient (active) or a gymnast (passive), or the exercises could be performed by a patient with the help of a gymnast (combined). Movements of the body themselves were at issue, and on a theoretical level it did not matter who or what moved the body and caused the desirable organic and curing effect within the body. A little dog would do just fine, then, and treating the cancer by movement did not necessarily require any physical effort from the female patient herself.

Still the question about moving the woman’s body remains. In this case, neither the woman herself nor the little dog moved it visibly or physically. So, where did the actual movement take place, and how should movement be defined in the first place? According to the physiological laws of the time, a crucial element affecting the body was energy, also known as heat, animal heat or vital power. This vital energy could be modified through exercise or nutrition, for example, because it was connected to the circulation of blood, the respiratory system, and digestion, i.e. parts of the physiological system of the body. The skin, in turn, played a central role in regulating the body temperature. Touching it in different ways—by chopping, point fulling, concentric fulling, stroking, vibrating, or even sucking— was thus deemed a relatively common part of different movement-cure exercises. As I see it, then, the case of the cancer patient and her dog was perfectly in line with the physiological understanding of the body in the context of mid-nineteenth-century Britain. As the little dog was sucking on the nipple, the skin around and on the nipple was activated, which in turn affected the organic bodily functions underneath the skin, such as the blood circulation and body temperature. Activating the skin and causing the organic and healing effect was the core mechanism that defined this odd performance as a plausible part of movement-cure.

While the performance of sucking a nipple was certainly not considered as a common part of exercise routines, this case sheds light on the diverse array of meanings “movement” carried within the context of physical education and the purpose the latter held for contemporaries. As Roth and other British physicians and social reformists were trying to design science-based exercises that would bring about a healthy body, their instructions encompassed two kinds of movements: some directly referred to the desirable organic changes in the body, while others aimed at producing these changes. According to Roth’s health manual, the “organo-mechanical movements” of the body could be divided into invisible and visible movements. “The first are manifested only by their effects,” which is why “all the functions of the vital power, the mind, intellect, sensibility, and the material organs serving as the dynamic agents in our organism – – show themselves materially – – in their effects.” On the other hand, Roth categorized involuntary functions of the body—such the motions of the heart—into “internal organo-mechanical” movements that he perceived to be visible movements.

In consequence, the nineteenth-century meaning of “movement” should be conceived of much more broadly than we would assume today: movement did not narrowly refer to physical exercises but more generally to any kind of action that could have an organic or physiological effect on the body. As a concept, it was grounded in both the materiality of the body and a culturally contingent understanding of how that body functioned. The case of the breast-cancer patient Roth featured in his manual is a case in point: from the viewpoint of cultural history, its most interesting facet is thus not whether the patient’s breast cancer was actually cured, but rather the contextual logic in which sucking a nipple as a movement-cure was deemed a successful remedy.

Lotta Vuorio is a doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on the moving body in nineteenth-century Britain, and the lived experience of physical exercises in various forms. She is interested in experimental ways of representing the past in the present, which is why performativity touches upon her research both in theory and in practice. She is also known for her Finnish history-themed podcast called Menneisyyden Jäljillä (On the track of the past) that popularizes historical research and gives voice to fascinating topics that are highly significant in this day..

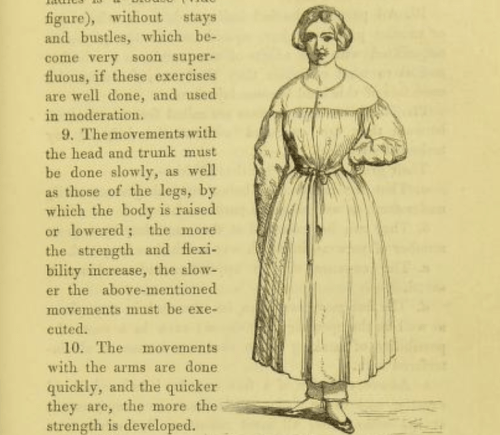

Featured Image: Illustration from Mathias Roth’s The Prevention and Cure of Many Chronic Diseases By Movements, p. 123.