By Charlotte Meijer

The Dutch Enlightenment has often been characterized as moderate and protestant compared to its counterparts elsewhere in Europe. This was partly because, as Dorothée Sturkenboom has argued, thinkers in the Netherlands sought to unite Christian revelation and reason, rather than using reason to critique Christian thought. Moreover, as has been shown by Eric Jorink, the discourse on the so-called liber naturae, or book of nature, was more uniform in the Netherlands than in other European countries. One characteristic expression of these beliefs was the idea that good Christian practice involved improving one’s knowledge of the natural world.

In the following, I will explore how ideas about religion and the natural world were connected in the Dutch press, using examples from three periodicals which have thus far received relatively little attention from historians: the Verstandige Natuuronderzoeker (The Sensible Scientist, 1751-1753), the Natuurkundige Verlustigingen (Natural Delights, 1769-1778) and the Ryk der Natuur en der Zeeden (The Empire of Nature and Morals, 1770-1772). Research by Joost Kloek and Wijnand Mijnhardt estimates the number of publications in the eighteenth century to be double what it had been in the previous century, with about 200,000 titles published. Periodicals like the three addressed here—which were not quite newspapers, but not ‘regular’ journals either—would appear around two to three times a week, with themes ranging from science and news to satire and opinion. Their contents reflect changes on the political and intellectual scene both domestically and abroad: as the Enlightenment spread around the world, the Netherlands was building towards a year of revolution. In 1795, the ruling house of Orange collapsed, and revolutionaries seized power with the help of French allies.

The Dutch Republic was a promising place to explore new (religious) ideas. Historians still generally agree the Dutch were relatively tolerant in religious matters, but religious freedom differed by religion and by jurisdiction. Toleration, moreover, relied less on benevolence and more on the fact that the Dutch Reformed Church was itself a minority, so it would have harmed political stability and prosperity—and been practically impossible—to engage in widespread religious persecution. Nonetheless, this relative openness made an attractive refuge for people whose religion or ideas weren’t tolerated in their own country. Indeed, as Geert Janssen has argued, even contemporaries characterized the early modern Netherlands as the ‘republic of the refugees.’

In this unique context, according to Ernestine van der Wall, the European trend of theology losing its hold on intellectual culture and being replaced by new philosophies had distinctive effects. Across the continent, one religious response to this trend was the rise of physico-theology. This movement used new scientific findings to make arguments for divine creation, examining the relationship between nature and God. Dutch intellectuals quickly adopted this approach under the name godgeleerde natuurkunde.

The most common strategy for uniting God and nature was to describe nature as a second book of revelation, as Jorink’s study of the liber naturae demonstrates. Although the idea of the liber naturae could be found in many Protestant countries, it was only explicitly included in the confession of the Dutch Reformed Church. In the Verstandige Natuuronderzoeker, written by the Dutch doctor Johannes Wilhelmus Heyman (1709-1774), we find one of the clearest expressions of this idea of nature as a book of Scripture:

Because the most honored and revered book of H. Scripture, through which the Supreme Being has liked to reveal himself to us humans, consists, so to speak, as of two parts, of which the first is Nature, and the second the Revelation, and of which the latter steadily exhorts us to consider the first. Both should therefore be considered with great attention

Heyman emphasizes how the world is a ‘stage’ that proves the existence of a perfect, eternal Supreme Being, who is both the creator and organizer of everything (p. v; 1777). He even declares how lucky he is to be alive at a time in which people have been ‘pulled from the former darkness’ and ‘put in broad daylight’ (p. vii; 1777), a clear reference to the Enlightenment and a reminder that these ideas were (at least partly) inspired by what Anne-Charlott Trepp characterizes as the ‘rational cognition of nature inspired by the Enlightenment’ (p.137; 2020). According to Ann Blair and Kaspar von Greyerz, these ideas of a rational, omnipotent, and wise God who is actively present in the natural world were some of the key characteristics of physico-theology across Europe (p.7-8; 2020). But, in the closing words of the final installment of the Verstandige Natuuronderzoeker, Heyman takes this argument further and argues that God has kept caring for ‘miserable’ people even after the Fall, seemingly believing in a God that is still actively involved in human affairs, rather than only as a creator of natural phenomena as many of his contemporaries believed (p. 201; 1777).

The idea of Nature being God’s second book of revelation appeared again in Natuurkundige Verlustigingen, a periodical written by the Dutch amateur zoologist Marinus Slabber (1740-1838). Here Slabber, an elder of the Protestant Waalse Church, describes what he saw as the Christian duty to learn more about God through nature:

But also, on the other hand, the research of Nature is our duty, because of all Creatures here on Earth, we are the most admirably created Creature, gifted with reason, which makes us Human: so we are the most perfect; so that we, above all other creatures, can glorify God in the most perfect way in his complete creation

By giving thorough descriptions of insects and organisms that can only be observed through a microscope, Slabber intended to show his readers all of God’s wonders, provoking awe, and, in turn, reverence for God. As shown by Jorink, this idea that even the ‘lowest’ creatures are worthy of attention – and, accordingly, can be used to increase the awe for God – was popularized nearly a century earlier by Dutch scientist Johannes Swammerdam (1637-80). The Dutch interpretation of physico-theological thought was thus embedded in much older traditions of thinking about God and nature in the Netherlands.

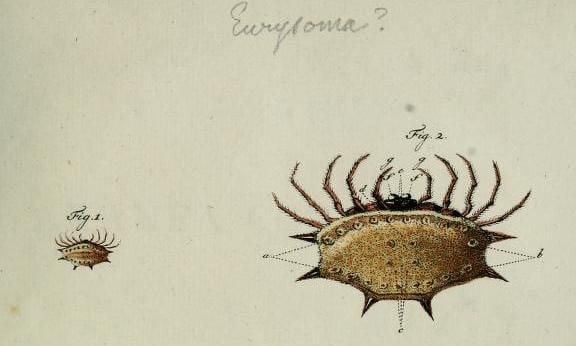

Slabber does not, however, pretend to know everything about every little creature. For example, when he writes about the spinybacked orbweaver (aranea conchata), Slabber observes that the spider has something resembling eyes, although they don’t seem to function as such, and declares that he does not know why the Creator put them there. But ignorance is part of the argument, as he later writes, ‘…we, mortal Creatures, will never know the true goal of the wisest Supreme Being,’ (p. 65-66; 1769). He then proceeds to describe the placement of ‘real’ eyes and argues that their intricacy shows God’s inscrutable wisdom (p. 5-7; 1769). Even unassuming creatures, like worms and fleas, are described with a sense of awe, and are, according to Slabber, ‘worthy of the astonishment of a being gifted with Reason.’ (p. 23; 1769) Using personal scientific insights to show God’s might and care in creating Earth, Slabber’s Natuurkundige Verlustigingen is a prime example of how practitioners of godgeleerde natuurkunde combined the new scientific tradition with the older biblical one.

A second religious response to the growing influence of Enlightenment philosophy was the emphasis on piety. According to recent research by Joke Spaans and Jetze Touber, religion in the eighteenth century ‘gradually distanced itself from its sixteenth century confessional moulds’ and shifted its emphasis to the Christian lifestyle. Piety remained a central aspect of Christian writing and became ‘increasingly identified with civic virtues’ (p. 9; 2019). On the other hand, Blair and Von Greyerz identify a more conflictual aspect to the new literature, with polemics against deism and atheism being one of the main components of physico-theology (p. 7-10; 2020). On this point, there is greater variation between the journals. Although a lack of sources makes it hard to pinpoint why, some authors preferred to emphasize the wonders of God’s creation, hoping to instil emotions of reverence, whereas others used a combination of showing wonders and scare tactics.

For Slabber, despite his role in the Church, the struggle against infidels was less relevant than for the other authors, who were actively opposing the perceived threat of atheism and deism. In the Ryk der Natuur en Zeeden, for example, the authors don’t hide their dislike of ‘people without morals’ and ‘godless’ people. Although originally published in German, the Ryk became popular in the Netherlands once translated. Its sixteenth instalment was dedicated to the question ‘How and when is the best time to tell someone without morals the truth?’ The authors cite the influence of the devil and Beelzebub (p. 121; 1771) and declare war on anyone promoting his ‘follies’ and ‘slander’ (p. 8; 1771). This more confrontational mode shows that physico-theology was not just a way for early modern thinkers to unite ideas about the natural sciences and the biblical tradition out of sheer curiosity, but also a very practical response to socio-religious changes of the time.

Heyman, in the Verstandige Natuuronderzoeker, not only warns his readers about the ‘godless’, but also about God’s revenge on them. He claimed that some natural phenomena, such as hail, were created by God as a form of revenge. The hail we know—not big enough to kill people on a large scale, but enough to scare them and occasionally destroy crops—is meant as an example (‘image’) of His ‘awful punishment and judgement of the Godless’ (p. 138; 1777). Here we see a less benevolent view of God as punisher, who not only uses nature to reveal himself but also to warn, and potentially hurt, infidels. To Heyman, this did not make God—a being of ‘infinite Goodness’ (p.iii; 1777) — any less good. On the contrary, it showed how much He cared about the safety of those who do believe. In this context, it is useful to remember that physico-theology was, at least in part, a response to the perceived threat of atheism and deism.

These late eighteenth-century periodicals offer a unique view into the minds of early-modern Reformed thinkers in the Netherlands. The growing influence of new philosophies, the fear that theology was losing its hold on society, and the perceived threats of atheism and deism led intellectuals across Europe to innovatively combine the new (natural) scientific insights of their time with ideas about religion. Far from the view that religion and science are antithetical, these authors regarded the scientific tradition as compatible with, and even proof of, the biblical tradition. It was knowing nature, after all, that would bring them closer to knowing the Creator.

The specific context of the Netherlands is no less interesting in this regard. Due to its climate of relative openness and toleration, the Dutch Republic became a place of international intellectual exchange, which led to stimulating discussions as well as fierce polemics. With the Dutch Reformed Church including the dogma of the liber naturae in its confession, the Dutch Republic proved to be a fertile ground for physico-theological ideas. It’s as if the journals have come full circle: from writing about a religious revelation to, in a sense, becoming a historical one.

Titular quote from Meier, G. F. e.a., Ryk der Natuur en der Zeeden, trans. G. Bom (Amsterdam, 1771).

The author would like to thank Dr. Peter Forshaw for his thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this essay.

Charlotte Meijer is a graduate student in history at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests include big history and environmental history.

Featured Image: R. Muys after P.M. Brasser after Martinus Slabber, Spinybacked Orbweaver, 1778, in Natuurkundige Verlustigingen, p. 1.