Tom Furse

Over the Christmas break and into January, I’ve managed to fit in several books and essays that have a partial theme about socialism and social reform. The first was Lenin’s Imperialism is Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), which was a slight juxtaposition as I was a willing beneficiary of global capitalism by eating Christmas food from around the world. It is a short analytical book with a polemical style. He doesn’t hold back his dislike of Karl Kautsky. Knowing now that Lenin became the leader of the Soviet Union while Kautsky became almost forgotten makes his criticism here almost comically earnest. I bought Era of Tyrannies (1938) by Élie Halévy in late 2021 and flicked through it but other work took over. I finally read it this month. It is a terrific collection of essays. He covers many issues, perhaps the most central was that European nations were heading toward an ‘era of tyranny’ through a merging of coercive state power, corporatism, and capitalism as a way out of the problems associated with modern global industrial and financial capitalist relations. I read a couple of William Hazlitt’s short essays, his ruthless putdown of Jeremy Bentham and the monotony of utilitarianism is well worth half an hour of your time. Lastly, Charles Dickens’s Hard Times. Although it is a social commentary about an industrial city in northern England, he isn’t that vivid about factories or machinery. The best writing is on characters, Gradgrind is terrible but Mr. Bounderby is the worst, and all power to Louisa.

Rachel Kaufman

Laura Levitt, Professor of Religion, Jewish Studies, and Gender at Temple University, recently published a beautiful book, The Objects That Remain, which dwells on the act of holding. Intent on approaching the ways in which objects brushed by violence become sacred objects through the tender act of custody, Levitt weaves together (while acknowledging the spaces between threads) her rape as a graduate student, police property management of criminal evidence, and objects held and conserved by institutions dedicated to Holocaust remembrance. The book is in conversation with Maggie Nelson, Edmund de Waal, Jewish and Christian notions of the relic, archival studies, and much more. A work which presses the boundaries of form quietly and surely, The Objects That Remain persists in weaving a story of justice, memory, and care as bound to knowing as it is to the remains which we can never fully know.

Oscar Broughton

At the start of 2022, I began reading Joshua Specht’s Red Meat Republic: A Hoof-to-Table History of How Beef Changed America (2019). This book analyzes the development of beef production in the United States during the late nineteenth century by creating a convincing narrative across five chapters. It begins with the remaking and standardization of land on the North American frontiers in order to make it suitable for cattle. This displaced indigenous communities and created different areas within the United States that began to specialize in parts of the bovine lifecycle. Cows were typically born in the South in Texas and then moved north to places such as Colorado and Montana where they were fattened. After the Civil War (1861-65) the integration of railway networks allowed national cattle markets to emerge. This allowed Chicago to become the undisputed center of meatpacking by 1890, which Upton Sinclair famously decried in The Jungle. Chicago was not only the center of meatpacking in the United States but also central to a global economy, literally helping to feed military forces around the world and supplying cheap beef products particularly in Europe and the Caribbean. As a result, the Chicago meatpacking firms rightly claimed to have democratized meat consumption as beef became cheaper and more accessible to the general population. New recipes and hierarchies emerged as a consequence highlighting how race, class, and gender were inseparable from dietary choices. Specht conveys all of this information while never forgetting to note the role of social and political choices made along the way, leading to a nuanced narrative that cuts against the fat of technological determinism that might otherwise be used to explain this story.

Jacob Saliba

Perhaps like many, I go to the novel as a means of quiet escape from the workload and responsibilities of academic research. For me, I have been drawn to the novels of J.K. Huysmans, a late nineteenth-century French Decadent writer turned avowed Catholic. Two of his works in particular have captured my attention: À rebours (Against Nature) and Là-Bas (Down There). Published in 1884, Against Nature is a psychologically playful and linguistically animating story of a solitary French bourgeois man struggling with great despair to find personal wholeness in the lifestyle he has inherited from his wealthy Parisian parents. It is a spectacular literary expression of French Decadence both for its historical richness as well as its general reading enjoyment. Down There, first published in 1891, provides an exciting shift in Huysmans’ outlook as a novelist. Having definitively cut ties with naturalism as a literary paradigm, he takes the reader deep into the caverns of the nineteenth century culture of the occult. Entangling Satanism with romance, unabashedly criticizing science by way of raw religious feeling, and explaining the history of the Church through cathedral bells, Huysmans experiments with religious consciousness not so much for its transcendental values but for its haunting inflections in lived experience. My suggestion is to read these books in order; that way one can feel the tensions in which Huysmans the novelist and Huysmans the person begin to evolve and take shape. Should a reader need more context to unpack these fascinating texts, I recommend Richard Griffiths’ The Reactionary Revolution: The Catholic Revival in French Literature 1870-1914.

Maria Wiegel

While reading Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth (1905), I couldn’t help but notice how relevant Wharton’s view on women still is today. The protagonist Lily Bart’s quest for prosperity and social status, which she hopes to find in matrimony, while also looking for love, does not merely reveal the flaws of capitalist early twentieth-century America. Much more than that, while reading about Lily’s dating life, it makes one wonder, in how far dating has changed by the early twenty-first century in our neoliberal western world (which went through several waves of feminism, already). Luckily, I could draw on a recent birthday present, Florence Given’s Women Don’t Owe You Pretty (2020), to gain a little bit of an overall view of the topic from today’s perspective. In this book Given, a British feminist and illustrator, deconstructs women’s performativity under the male gaze, while drawing on her own experiences (I am aware of Chidera Eggerue’s critique on Given’s book and will elaborate on this issue, as soon as my copy of What a Time to Be Alone (2018) arrives and I get a chance to read it). Interestingly, in Wharton’s novel, Lily Bart’s fall from grace—due to the upper class’ male and female influences, coupled with her naiveté—reflects what Given describes in her book; namely that “abuse in our society is normalized” (97). What I think is especially interesting in both Wharton’s novel and Given’s book, is that abuse is not exercised by men only. Additionally, women themselves often reproduce patriarchal structures, instead of fighting them. This, however, often happens unconsciously (e.g. by establishing and maintaining stereotypical figures, such as ‘the other woman’ or ‘the basic bitch’). I think both books provide ample food for thought and I would recommend reading them together, since they show how little has changed ever since Wharton voiced her discontent with women’s place in society. Maybe even more importantly, they induce one to rethink one’s own behavior and thought patterns.

Emily Hull

During the winter break, I finally sat down to read a number of journal articles which had accumulated on my “to read list” throughout the previous term. In the course of my reading, I particularly enjoyed Nick Devlin’s recent article “Hannah Arendt and Marxist Theories of Totalitarianism.” Devlin revisits Arendt’s masterpiece The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), a text which was fundamental in shaping Cold War intellectual life in America and across the Atlantic. Crucially, he suggests that Origins should be viewed as three different theories of totalitarianism. The most interesting element of the article is his discussion of the first two parts of Arendt’s classic volume where he argues that Origins can be better understood within the history of interwar Marxist thought on totalitarianism. Here, he specifically analyzes the way in which Arendt relied on the same languages of imperialism and Bonapartism as the interwar Marxists had done. Furthermore, he also presents an enlightening discussion of ex-Marxist intellectuals, such as James Burnham, and demonstrates the links between their work and Arendt’s. In short, the article is an excellent read for those interested in the work of this vital twentieth-century political theorist and seeking a greater understanding of the historical development of theories of totalitarianism.

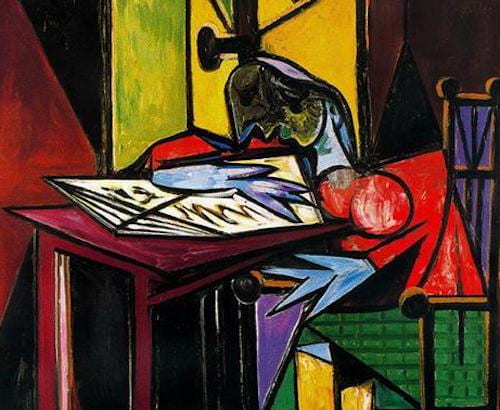

Featured Image: “Woman Reading,” Pablo Picasso, 1935.