By Or Rosenboim

What do women know about international politics? To the informed twenty-first-century reader, this question may seem absurd or inappropriate. There are many women who do world-leading research in international relations, and others— perhaps not as many as I’d like—occupy key international political roles in governments and institutions. But if one looks at the conventional “canon” of thinkers in international relations, it seems that no woman has ever contributed to debates about international affairs, or indeed given serious consideration to such themes. The study of international relations was, apparently, a man’s job.

The new anthology of women international thinkers, which accompanies an edited volume on the same topic published last year, is a long-due addition to scholarship on politics beyond the state. Indeed, its forthcoming appearance, in the summer of 2022, seems much too late. It is an essential, even revolutionary contribution to international studies, showing the fundamental role played by women in shaping the academic discipline of international relations (IR) as well as international thought more broadly.

This welcome collection is a compelling testimony to the significance of women international thinkers. It features predominantly British and American thinkers, and there is surely a great scope for future research and new anthologies that would feature voices from other areas of the world such as Central and Eastern Europe or the Global South. Yet more than anything, the book presents the discipline of IR with the uncomfortable truth about the exclusion and omission patterns that have shaped its self-image.

In recent decades, scholars have already expanded the boundaries of IR as a field of knowledge and academic inquiry. Robert Vitalis showed how Black scholars were excluded from American debates on world order. Robbie Shilliam, Alexander Anievas and Nivi Manchanda brought the notion of race to the forefront, engaging with the discriminatory and Western-centric legacies of IR. Other accounts of disciplinary history grounded its birth in British imperial thought, highlighting the racial prejudices that motivated its establishment. While there has been a surge in scholarship on Indian, Japanese or African international thinkers, though, relatively little attention has been dedicated to women’s contributions. An unsuspecting student might imagine that indeed, women played only a marginal role in the development of international thought, apparently limited to the theme of “gender.”

The new anthology demonstrates that this myopic image of a women-less discipline is far from the truth. Patricia Owens has already shown elsewhere how women were systematically excluded from the disciplinary history of IR and how their role in shaping the field has been undermined. Women thinkers rarely feature in anthologies of “great international thinkers,” who in turn are often described as the “founding fathers” of the discipline. This intentional erasure is not only unjust towards past thinkers but also towards contemporary woman scholars and students who encounter a historically incorrect, deeply gendered, and essentially unwelcoming representation of the discipline.

In an ambitious and wide-ranging attempt to take stock of dozens of neglected, ignored, under-studied, and excluded figures, this collection offers an alternative view of the state of the field, re-drawing the contours of our knowledge about IR and its historical genealogies. Women were there, in crucial crossroads along the discipline’s development, and contributed a great deal.

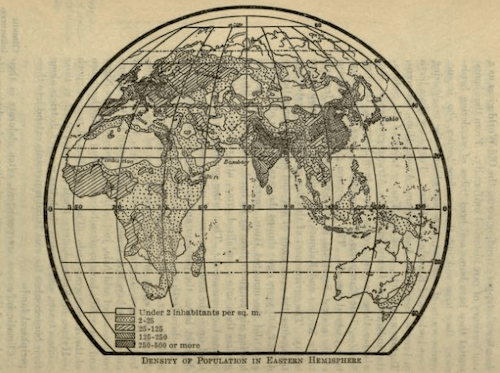

The thematic division of the anthology, which includes chapters on immigration, war and peace, education, religion, demography, immigration, economics, law, decolonization, and the environment, reflects the versatility of women’s role in IR as a field of scholarly investigation and simultaneously redefines what “counts” as IR scholarship. In the section on geopolitics and war—key themes in traditional conceptions of IR—the selected contributions demonstrate how women thinkers shaped political discourse. Ellen Churchill Semple played a major role in introducing the study of geopolitics to the United States. Sylvia Pankhurst, well-known for her suffragist activism, and British journalist and activist Claudia Jones are rarely included in the canon of geopolitical thinkers, but they also had an original take on world order, empire, and conquest. Pankhurst advanced an effective critique of fascist Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia in 1938[1], while Jones showed the failings of British imperialism in India in 1942.[2] Their views were no less valuable and prescient than those of their male colleagues.

The anthology clearly demonstrates the need to expand the definition of who “counts” as a geopolitical thinker, which is one of its most path-breaking contributions. Challenging the notions of inclusion and exclusion in the field of IR is not merely a scholarly exercise in the ever-lasting quest for new perspectives on international politics. It is a call to rethink what is considered as knowledge in IR and who can produce it. In this sense, the anthology can be read as a political manifesto against disciplinary gate-keeping, which has limited women, but also non-white, non-western, and other marginalized groups, from expressing their views on international relations—at the discipline’s loss.

Hopefully, the thinkers in this anthology will not be fenced into the category of “women international thinkers,” but will be considered, simply, as international thinkers. The wide range in this volume shows that women engaged with all aspects of IR. The interest in their perspective needs no collective justification—each should be judged for the merit of her own ideas, alongside male thinkers.

As the editors rightly suggest, this volume can only be considered as a very first step towards a much larger, necessarily collaborative project to bring to light the ideas and texts of women international thinkers. Other linguistic and geographical spheres should be explored, institutional settings and political organizations should be investigated. But it makes little sense to point out the missing thinkers in this volume, as the editors themselves encourage the readers and the discipline to continue the exploration and contribute to the collaborative project of redefining the meaning of knowledge production in IR.

[1] Sylvia Pankhurst, “The Fascist World War (Ethiopia and Spain),” New Times and Ethiopia, 1 August 1935, reprinted in The Sylvia Pankhurst Reader, ed. Kathryn Dodd (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), 214– 216. [pp. 92-93 in the Anthology]

[2] Claudia Jones, “What We Must Now Do about India,” Weekly Review, 25 August 1942, 8–10. [pp. 105-109 in the Anthology]

Or Rosenboim is Senior Lecturer in Modern History and Director of the Center for Modern History at City, University of London. She is a historian of political thought, and her work focuses on international thought in the twentieth century. She has published on the idea of globalism and on various theories of world order in British and American political thought. She is also interested in geopolitics, Italian international thought and imperial history.

Featured Image: Illustration from Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1911).