By Barbara D. Savage

It is one thing to argue for the expansion of existing canons, but another to actually do it, and harder still to create an altogether new one. Yet that is exactly what Women’s International Thought: Towards a New Canon, the first ever anthology of its kind, sets out to do. Its ambition is as brazen as its achievement, realized in just under a hefty 800 pages. This collection samples the writings of a diversity of women, ideas, and locations spread across much of the twentieth century and spanning a broad array of themes and interventions. It has the potential to be as foundational a work as Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s 1995 volume Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought.

The introductory essay outlines the depth and diversity of women’s ideas, locations, and arguments while standing itself as an illustration of why this work is both so necessary, so overdue, and so valuable. It frames this work not merely as reclamation—although it is that too—but rather as restorative work that puts women back into a field which they helped create: “Despite women being at the forefront of international thought throughout the twentieth century, their ideas were often stolen and, if not, then ignored.” (3) This book is an audacious effort to right that wrong, while also calling for a re-imagining of the field and its history in ways that expand and enrich it.

The ordering of the materials into 13 broad categories may on first glance look like a gathering of the usual suspects—among them, geopolitics, war, imperialism, anti-colonialism, international law and organizations, diplomacy, world peace—but within each grouping are surprising affiliations, stitched together by brilliantly rendered contextual essays. In those, biographical sketches permit a reader, however unfamiliar they might be with each woman, to place their work within a complicated life and varied intellectual influences. But unexpected topics also are deployed, including religion and ethics, technology and environment, and population and immigration, to cite a few.

This printed gathering of women’s voices brings into one space women thinkers rarely found between the same book covers. Yes, it features Hannah Arendt, Anna Julia Cooper, Agnes Headlam-Morley, Merze Tate, and Simone Weil—but also Rachel Carson, Amy Jacques Garvey, Mary McCarthy, Eileen Power, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and Louise Holborn.

One of the many strengths of this collection is its patent rejection of racial tokenism, as a variegated group of Black women are not confined to one section but are represented across nearly every category. Nor are the ideas they present confined to questions of race or imperialism or anti-colonialism; instead, they represent a range of expertise and concerns. The broad reach of their writings reflects their differing historical locations and moments, as well as starkly different ideological orientations and intellectual backgrounds.

That said, should one want to eschew Adele’s recent admonition against “shuffling” the carefully arranged ordering of her recent musical release, this collection lends itself to all sorts of improvisational links across and even beyond the carefully designed section headings. For me, that was a special temptation as a scholar of Black women’s intellectual history, as I encountered fresh reminders of the many places where the women featured found themselves, whether in Zurich speaking to the International Women’s Congress (Mary Church Terrell) or analyzing the constitution of Ghana (Pauli Murray) or reporting on the first Pan-African Congress (Jessie Fauset) or arguing for African influences on Catholicism (Zora Neale Hurston). Those represented are activists, scholars, religious workers, all drawn together here by their gifts as writers and orators, and often by their experiences as cosmopolitan world travelers. This invites even more digging through archives and printed materials, giving further evidence of the willed erasure of Black women’s voices from international debates, moments, and gatherings in which they actively participated.

Among the greatest beneficiaries of this work are our students, not just in the field in which the book is situated, international thought, but in the many adjacent sister disciplines, including economics, anthropology, diplomatic history, religious studies, the history of science and technology, Black studies—fields not often brought into conversation with one another despite overlapping concerns. This collection of primary materials also begins to demonstrate how much work women thinkers did on topics where they were not expected to have authority or expertise, or where their ideas were discarded or overlooked.

Women’s International Thought really does represent the proverbial tip of the iceberg of a much larger but still submerged body of women’s intellectual and political labor. Sometimes the trite metaphor is also the truth. The anthology’s range and reach should only encourage more work and more research, even as this volume is a gift to all who teach and write in any of these fields.

And for that, we are in debt to the women whose years of labors and sacrifices brought it into print. They take care to emphasize the “towards” in the book’s title, inviting all of us to help build this new canon and to have it trouble the old in our teaching and our research. This collection now serves as a model for moving forward in ways that are as capacious and as creative as what is presented so brilliantly here.

Barbara D. Savage is Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought in the Department of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2018-19, she was Vyvyan Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at Oxford. Her forthcoming intellectual biography of Merze Tate is at press and expected in 2023.

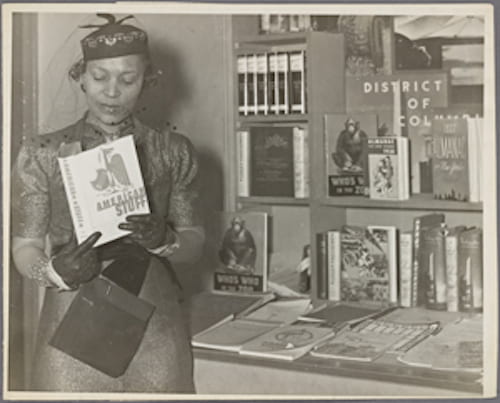

Featured Image: Zora Neale Hurston at the Federal Writers Project booth at the New York Times Book Fair, 1937. Via the New York Public Library.