By John DiMoia

In early 2009, the New York Times featured an article in the midst of the global financial crisis, pointing to a recent downturn in the shipping industry. Titled “Cargo Ships Treading Water Off Singapore, Waiting for Work,” the piece referred to a set of related developments stemming from the regional effects of economic slowdown. First, an unusually large number of container ships had to wait in close proximity to Singapore, seeking contents to acquire before continuing on with their journey. Typically, these large vessels travel a circuit between Mumbai and Shanghai. Although these types of ships can also be located at several key nodes around the world, Singapore holds a special place of significance for its positioning midway between India and China. British colonial officials anticipated precisely this style of trade between South and Southeast Asia when they selected the site in the early nineteenth century, and this fact was further reinforced with the growth of East and Southeast Asian economies after 1945. The recent use of technologies and shipping by imperial and nation-state actors reflects the attempt to capture the activity of these earlier trade networks, like those of the Malay world and the Indian Ocean. Scholars such as Sunil Amrith have made the case for the latter as a site of networked trade and travel.

The story of technological innovation through shipping containers, the focus of this piece, relies upon these earlier networks, even as the history is often written from a European or North American standpoint. The “cargo ships” referenced here, most likely large container ships, represent another example of recent technological development contingent upon these earlier structures, as trade has long moved through the Straits of Malacca via other means of conveyance.

The literature concerning logistics and shipping has experienced a dramatic revival since 2019, with the COVID-19 crisis reminding us, as the 2008 financial crisis demonstrated a decade ago, of the materiality underlying the infrastructure for much of the global economy. In a development closer to many Americans, both physically and metaphorically, empty ships sit outside Long Beach and at other West Coast ports, waiting to receive cargo. Other ships arrive bearing cargo but must wait to be unloaded, due to lengthy backlogs at port facilities. With the COVID pandemic leading to dramatic increases in online orders, and further associated with consumers’ desire to maintain social distancing through e-commerce, the shipping industry finds itself in a position to make record profits. Still, the realities of crowded ports, extreme labor shortages, and the inability to move contents rapidly in and out of ports continues to undermine the industry’s positive economic situation.

From Colonial to Post-Colonial Transport Intervention (1945- ):

A Brief History of the Supply Chain

Within the vast body of work on supply chains, a few generalizations help focus its scope. The term suggests a set of links bringing together objects of value, reassembling them to make something new or more saleable, and equally important, readily available to the market. Thus, the typical supply chain involves the removal or extraction of a natural resource from its environment, subjecting it to an industrial or related process of transformation, and then bringing the object to sale. Although the term clearly holds relevance in numerous time periods and national contexts, it is most frequently at the intersection of imperialism and early forms of industrial capitalism. To this end, some historians have argued that Early Modern European organizations involved in trade and colonization, such as the VOC (Dutch East India Company), represent perhaps the best early embodiment of this concept of the supply chain, corresponding to the expansionist impulses of the early 17th century.

The concept of the supply chain carries strong implications of legal and corporate bonds structuring capital in particular ways, and again, this claim remains fairly consistent with a discussion of early modern systems and the transition to capitalism: a brief list of the elements involved in the creation of the “supply chain” as we know it today includes newer types of bureaucracy, accounting practices, and changing conceptions of time. The phrase “supply chain” is often used in military contexts, especially in reference to expeditions involving the management of large quantities of soldiers, equipment, and food. If ships powered by sail or oar required places to dock for sources of potable water and to replenish food supplies, these types of concerns became even more acute with the introduction of steamships (which required regular replenishments of fuel, in the form of coal) and other mechanized vehicles in the second half of the nineteenth century. Napoleon’s assault on Russia is often cited as an example of the problems associated with maintaining supply chains under harsh winter conditions. Food spoilage was one of the campaign’s problems. Seeking to lengthen the period available for safe consumption, Napoleon’s troops transported food in canning jars.

Given this loose grouping of corporate and military contexts, it is not surprising that the term “supply chain,” along with the related category of “logistics,” started to appear more regularly in print in the late nineteenth century with the growth of a bureaucratic, managerial culture. As defined in the Oxford English Dictionary, both terms can be used to describe the movement of troops, the management of goods and resources, and especially, the need to promote some kind of productive relationship between the two. In contemporary usage, the concept of the supply chain often involves the multinational corporation and its drive to reach multiple markets across national, regional, and international borders, linking storage and manufacturing sites based around the globe. However, in packaging together corporate and military forms that lead to a particular view of capital, this discussion tends to center the history of the supply chain primarily in the historiography for Western Europe and North America. Recent work in the history of capitalism complicates such a comfortable starting point, as does the revised container story offered here, which argues for a prominent role of East and Southeast Asian actors.

Among the factors complicating supply chains, along with distance, weather conditions, intervening parties, and transport infrastructure is the question of packaging. The literature on standardization highlights the difficulties in persuading national actors to agree to a set of metrics, and these observations hold as well for shipping a diverse array of objects over a long distance. Well into the mid-twentieth century, and still used today, break-bulk shipping permits objects to be sent in a range of different containers (boxes, drums, crates), with many container forms specific to particular industries. In terms of both loading and unloading, this approach adds considerable time and labor, and suggests the image of stevedores working on docks. The possibility of eliminating these needs and streamlining the process occupied the attention of many imperial actors, especially those with supply needs.

The most common explanation for the origins of standardized forms of packaging (boxes, containers) assigns the primary impetus for the development of these forms to private concerns and the merchant marine industry. These narratives focus largely on Western Europe (shipping) and the United States (interstate highways, trucking), covering a period roughly from the 1920s through the 1950s. At the same time, the role of logistics, and containerization in particular, underscores the significance of the Pacific region. East and Southeast Asian actors have played an enormous role in mobilizing and implementing much of the technical infrastructure undergirding such economic cooperation.

During World War II, the Pacific theatre placed an additional strain on the ability of the United States to keep troops supplied, placing renewed emphasis on military logistics. The military sought urgent solutions to the problem of how to pack and ship more efficiently. While the idea of designing a kind of standard container, whether wooden or metal, precedes this period, the US military ultimately had the will to make the hypothetical construct a reality. At some point during the war, the “Transporter,” a container constructed for the possessions of individual soldiers, received its trial. These logistics concerns continued through events of 1945, as the joint occupation of Japan (GHQ, or General Headquarters, 1945-1952) and Korea (USAMGIK, or United States Military Government in Korea, 1945-1948) brought an increased Pacific presence, augmenting U.S. interests in Guam, Hawaii, and the Philippines established in the nineteenth century. During the Japanese occupation, private engineering firms and shipping concerns began to carve out a role for East Asian actors, who acted initially as subcontractors but were able to expand their role over the next several decades.

In keeping with this Pacific story, the next stage was the CONEX box (Container Express), a standard unit for shipping personal possessions that was introduced during the Korean War (1952) and its aftermath. Compared to the Transporter, the CONEX represented something of a streamlined update and carried its function beyond the war. Diplomatic historian Patrick Chung emphasizes the wartime context in particular, especially the southeast port city of Busan that became a logistics center, with the US supplying the Korean peninsula from nearby Japan. Previously a key port within Joseon Korea (1392-1910), Busan went from an imperial link (1910-1945) to a transformed South Korean port city, one of the first Asian ports to work with these new sets of technologies: boxes, cranes, and the types of ships designed to handle them. In the post-1953 setting, the CONEX received a great deal of attention, with late 1950s publications mentioning specifically that it had helped in Korea, and might prove even more valuable in any future crisis. The standard ISO (International Organization for Standardization) container had yet to appear (1968), but arguably, the wartime context of the Pacific played a significant role in enlarging and strengthening American military supply lines.

The CONEX box in use, offering an intermediate stage before the ISO container. (Source: CONEX: A Milestone in Unitization, 1957).

For much of the 1950s, East and Southeast Asian ports received ongoing attention—improved rail lines, port dredging and enlargement, and refurbished railroad lines—as part of post-1945 reparations. For example, Japan, as a defeated power, had to repay its debts, and it offered its expertise in the form of technical assistance and know-how rather than financial pay-outs. This brought Japanese engineers to sites such as Burma and Vietnam, sometimes with the very same wartime engineers who now reappeared under the guise of post-war development or technical assistance. Thailand was more complicated, as it had been a Japanese ally. As part of its transition to becoming an American Cold War ally, the Thai government (or RTG, Royal Thai Government) received significant amounts of American aid and technical assistance, much of which went towards augmenting its transportation infrastructure, and linking Bangkok to the various parts of the country. This hardware served a dual purpose: it allowed for military mobility, whether for domestic policing or protection, while also linking Thailand and neighboring Southeast Asian countries to the world market.

In 1959, DMJM (Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall), a Los Angeles architecture and design firm, undertook a series of projects on behalf of ICA (International Cooperation Administration), the predecessor agency to USAID (United States Agency for International Development).1 Specifically, DMJM was commissioned to improve Vietnam’s public works, especially its waterways, which constituted an important factor given the surrounding environment of the Mekong Delta. A few years later, DMJM undertook a further contract, one designed to study and make recommendations for Vietnam’s ports. This second set of studies, which went to publication in 1965-1966, offered an exhaustive look at the ports and their readiness for shipping. As of the early 1960s, Vietnam’s ports, linked to sites such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and neighboring parts of East Asia, used break-bulk shipping as the primary method of handling cargo. Teams of stevedores handled objects by hand, typically using nets and hand-implements, and much of this material was packed irregularly in bunches or batches.

In the Vietnam setting, DMJM noted that existing methods would not be sufficient to handle the expected inflow of traffic, whether on a wartime basis or not. As American forces prepared to arrive in larger numbers (1965), the method for supplying them consisted of dropping large quantities of goods along the beach, where they would wait for processing. Pilferage was common, as there were not yet warehouse facilities, and military bases were also only under construction at this stage. Even the containers available at the time, primarily the CONEX, required a combined hardware and infrastructure investment not available in Vietnam including features such as deeper ports, docks, loading / unloading bays, and larger cargo / construction cranes to handle the boxes. To address these circumstances, the US Navy implemented a crash construction program in three stages. Dredging work enlarged the ports deemed suitable, allowing for the passage of larger types of ships. To unload, temporary docks, or Delong piers (a series of floating platforms), came from the West Coast, with assembly taking place in the Philippines at Poro Point. The docks arrived at sites such as Cam Ranh Bay, where they were installed to allow for unloading: Cam Ranh Bay DeLong Piers: Research and Development Progress Report 9 1967 US Army; Vietnam War on Vimeo.

Cranes were not yet available as a uniform means of unloading, and in some cases, the boxes could be unloaded directly to the dock with other types of machinery. The LST (landing ship, tank or tank landing ship) allowed for cargo to be wheeled directly onto a surface such as a beach or shoreline. Previously, LSTs featured in amphibious landings, allowing tanks to roll onto a target surface. By 1966, ports such as Cam Ranh Bay and Quy Nhon witnessed a dramatic surge in deliveries, along with corresponding changes introduced to the speed of unloading, and the conveyance of these goods to troops in the field. Warehouses and other storage facilities, both at the dock and at newly built firebases, housed materials previously left unattended. In terms of supply lines, the military supply chain now reached from the West Coast, primarily Oakland and Long Beach, to the Philippines, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Although rarely receiving attention historically, private firms also assisted with transportation, with the airline Pan Am playing a prominent role in bringing American troops to Saigon.3

Sea-land shipping routes for 1964, pre-Vietnam, with a focus on Alaska and the West Coast, along with the American southeast. The firm generally receives credit for being the first to introduce intermodal containers (1956), and later ISO containers (1968). (Source: Sea-land Service, America’s Seagoing Motor Carrier, 1964)

Koreans, Port Labor, and Uses of Technology:

Vietnam and Beyond

If the official container literature starts with two contexts as previously noted—interwar European shipping and post-1945 American trucking—the East Asian story comes to life with two occupations (GHQ, USAMGIK), and then two wars: the Korean War (1950-1953), and the Vietnam War (1965-1975). Specifically, the post-Korean War side of this story introduces multiple actors on the Asian side of the Pacific, with South Korea making a gradual economic recovery by the early 1960s. In 1962, the ROK (Republic of Korea) placed its first KOTRA (Korea Overseas Trade Association) office in Bangkok, followed by the first overseas office of Hyundai Construction in 1964. These moves meant that Korean firms recognized the growing market in Thailand, and even more so in nearby Vietnam. With war arriving soon, the shipping firm Hanjin negotiated the right to subcontract for the US military, supplying Vietnam from Busan (1966-1969). The American firm Sea-land Service began its own Vietnam routes at about the same time, meaning that there were now a variety of private firms engaging in this dangerous, but extremely lucrative, form of trade. The Philippines also became an actor here, with Lusteveco (Luzon Stevedore Company) supplying labor for many of the Vietnam sites.

This collective activity meant that Vietnam was the recipient of CONEX boxes (via the U.S. Military) along with early forms of containers (via Sea-land, other commercial carriers) by about 1966, with American and Free World forces receiving their supplies in a timely fashion.2 The contrast between the CONEX and the ISO container coming into being lies with two factors: volume and standardization. The latter containers were much larger, and more importantly, rendered as standard devices meant for intermodal conveyance. In other words, ISO containers moved easily from ship to rail to truck interchangeably. Once adopted internationally, they also crossed borders as an established norm.

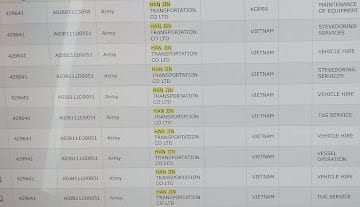

Shipping firms were among those receiving the most contracts during the Vietnam War, including examples such as Alaska Barge and Transport, and Asian firms such as Hanjin (Korea) and Luzon Stevedoring (Philippines). (Source: Records of Prime Contracts Awarded by the Military Services and Agencies, created 7/1/1965 – 6/30/1975, documenting the period 7/1/1965 – 6/30/1975 )

The American military intervention in Vietnam began in 1965, with the landing of troops at Danang. However, construction ran almost continuously from 1954, with the defeat of the French, and with the US subsidizing much of the French effort. With the scale of the war and the associated dangers, the US military therefore subcontracted many of its logistics tasks (1954-1965), which explains why these diverse sets of participants (and distinct national actors) were able to join, and why building began as early as the mid-1950s in Thailand, Vietnam, and neighboring sites. For its part, the Korean firm Hanjin proved its worth as a subcontractor by operating the port of Quy Nhon, supplying inland sites in Vietnam including Pleiku, meaning that responsibility for goods extended far into the interior. During the latter stages of Vietnam, East and Southeast Asia possessed at least two distinct, and rapidly growing, forms of shipping: the militarized routes from the US West Coast (CONEX boxes), and the private container routes coming from the US and Korea. In this sense, the Vietnam context sparked regional shippers (Japan, Korea) into recognizing the immense potential of this technology for commercial purposes. With the CONEX, boxes often traveled only one way and ended up as storage, or temporary shelter, in Vietnam. However, with Japan already having a strong export economy, and others (Korea, Taiwan) holding similar ambitions, the establishment of stable two-way routes with the West Coast made economic sense.

There is no firm consensus on which of these sites established priority with containerization, although many accounts cite Japan as the first adopter through its major ports in the Kansai region (Kobe, Osaka), dating to the mid-1960s. But as this account reveals, the conjoined factors of wartime contingency and the transnational links embedded with the Vietnam supply chain were essential for the rise of the container form. This was not a technology which simply migrated or travelled to East Asia, but in fact, firms in the region took the lead in the process of developing containerized shipping, eagerly linking Asian ports to West Coast hubs. For Korea, the wartime traffic continued, and as early as 1970, commercial container shipping began from Busan, even before the technology was adopted and fully integrated at the port site. Advertisements in Korean newspapers from the period illustrate new shipping lines organized jointly by Sea-land and Hanjin, running to and from North America. The Japanese shipper Kawasaki promoted a similar venture, offering competition within a rapidly growing marketplace.

The global introduction of the technology took place in sync with the growth of these routes and roughly corresponding to the close of the war in 1975. Korea filed for technology grants with the World Bank as of 1973, with major overhauls to its ports (Busan) taking place in the late 1970s through the early 1980s. Improvements included enlarged facilities for new container ships, cranes to handle ISO containers, and harbor dredging to allow for the passage of these new and larger vessels. Of course, South Korea also joined the shipbuilding market at about this time, with Korean shipyards in Ulsan beginning to turn out some of the world’s largest tankers. The commercial adoption and standardization of the ISO container meant that the wartime origins of the CONEX have almost vanished from memory, even as it remains central to the story of post-1945 East and Southeast Asia. Through the late 1970s, it would be followed by the economic transformation in China corresponding to the rise of Deng Xiaoping (1978), as most of the world’s largest container ports now occupy the densely populated stretch of coast between Beijing and Hong Kong.

This account does not include major elements of our present world: a more thorough discussion of post-1978 China, the rise of digital computing within logistics, the introduction of newer forms of networked communications, and the growth of e-commerce. However, this account can add to, and greatly enrich, a literature that relies on stories linking developments in shipping, trucking, and rail without taking into account the postwar occupations in the Pacific and two major wars (1945-1975). A narrative driven by Cold War logic and its perceived “success” places North America and Western Europe in a position of agency, reducing the impact of Pacific actors. Arguably, the containerization story involves a hybrid intersection between military logistics and commercial traffic, with these component parts overlapping a great deal in the late 1960s in Vietnam. Smooth stories of transfer fail to include the gritty materiality of these more nuanced local and regional stories, and what geographer Deborah Cowen characterizes as the “deadly life of logistics.”

As we contemplate further stoppages within international supply chains, whether linked to shipping, war, or materials shortages—the supply of DRAM chips, for example, has recently emerged as an important bottleneck—it is these kinds of stories that can offer a sharper and more telling version of competition among regions, rather than a uniform or flat story, one which radiates from abstract categories such as “The West” or the “Global North.”

Notes

1. DMJM performed this kind of work in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Okinawa, among others. At the same time, Vinnell often built airfields in recently occupied US territories.

2. In this context, “Free World” refers primarily to close American partners such as Korea and Thailand, part of Lyndon Johnson’s “Many Flags” campaign to bring in other national forces in a show of anti-Communist unity.

3. A number of civilian airlines conducted these routes, presumably anticipating the growth of air traffic following a South Vietnam victory.

Bibliography (PDF).

John P. DiMoia is Professor of Korean History at Seoul National University (SNU), and is also affiliated with STS (Science, Technology, Society). He is the author of Reconstructing Bodies, and one of the co-editors of Engineering Asia (with Profs. Hiromi Mizuno and Aaron Moore). He has held fellowships and visiting affiliations with the Needham Institute (NRI) at Cambridge University (UK), Kyujanggak Institute of Korean Studies (SNU, ROK), Asia Research Institute (NUS, SG), Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG, Germany), UCLA (CKS), and FAU (Friedrich Alexander University, Germany). He is currently a visiting scholar at UCLA working on a second book, titled, Peace and Construction: Korean Developmentalism, Built Environment, and Southeast Asia, 1954-present. He also serves on the editorial boards of several journals, including Social Medicine, and is on the advisory board for “Connecting Three Worlds.”

Find him on Twitter @JohnDiMoia.

Featured Image: Andreas Gursky, “Shipping Containers, Portsmouth, Virginia” (2017).

1 Pingback