By Joseph Puchner

While the political institutions of continental Europe convulsed in the wake of the French Revolution, spectators in Great Britain—a polity removed from the moment’s more-devastating geopolitical consequences—were busy putting pen to paper, reacting against such tremors from the comfort of their separated isle. The 1790 publication of Whig parliamentarian Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France inaugurated public debate over the revolution, and most importantly over its causes and its consequences. Such commentary persisted into nineteenth century, after the collapse of the French republic and the nation’s passage through both empire and a restored monarchy. To critical commentators of varied stripes, the French Revolution represented violent regime change, disregard for custom and tradition, contempt for established religion, and, even to an individual like Jeremy Bentham, a foolish attempt to establish ex nihilo a state based on a novel understanding of rights. To its sympathizers, such as the Romantic radical William Hazlitt, it was a promise of egalitarianism and a clarion call for social progress.

As historian Emma MacLeod notes, scholarship in recent decades has consistently revisited and reconsidered this so-called revolution controversy, in particular the extent to which it ought to be understood as a primarily Burkean moment—that is, as a public debate in which the subjects-in-question were effectively Burke’s arguments, more so than the actual revolutionary circumstances. Considering the primacy of Burke (and Burkean ideas) to the formation of revolutionary discourse within Great Britain beyond the 1790s. It can be incredibly helpful in tracing Burke’s role in the development of reactionary, counter-revolutionary, and even broadly conservative political discourse within the historiography of ideas (see John Whale and Emily Jones). Nevertheless, an overreliance on recourse to this Irish Whig—or, in some cases, on synthetic constructions of some corpus of Burkean doctrine—can result in a smoothing-over of the nuance and distinction of other, unique threads of political thought.

One episode lost in these cracks is the reaction to Spain’s liberal revolution of 1820. In 1825, Henry John George Herbert (1800–1849)—otherwise known as Lord Porchester (and, eventually, the Third Earl of Carnarvon), a youthful aristocrat from Hampshire—published a lengthy poem, The Moor. It offers a Romantic account of the fifteenth-century fall of Granada to Christian armies. While nearly all scholarly attention given to this work has focused on its merit as an exemplar of amateur Romantic literature (see Diego Saglia and Sara Medina Calzada), its eighty-page introduction and extensive explanatory notes contain broad commentaries on the social and political state of contemporary Spain. These insights disclose Porchester’s keen awareness of both contemporary debates on Spanish politics as well as broader counter-revolutionary arguments in support of aristocratic and clerical interest, local sentiment, and ancient customs and institutions—themes which Burke himself elaborated in his Reflections.

Porchester’s commentaries throughout The Moor, however, develop a further perspective on revolutionary activity in Spain. In offering a critical appraisal of the abortive constitutional regime framed in terms of the failures of the French Revolution, Porchester re-challenges a thread of argumentation employed first by Burke’s most vociferous opponent, Thomas Paine: his hopes for a future of states governed by written constitutions. While liberal constitutionalism was no godless republicanism, Porchester nevertheless contested both its revolutionary tendencies as well as the perspectives of individuals such as Bentham, who saw a written constitution—in particular, the Constitution of Cadiz implemented during the liberal revolution of 1820—as a guarantor of future Spanish liberty. Porchester’s comments on Spain instead consider the extent to which constitutions themselves were tools for revolutionary ends.

In the autumn of 1821, after a summer in Paris, Porchester visited Spain for the first time. He hoped not only to take in the sights of its castles and countryside—a constant source of inspiration for the young Lord’s literary endeavors—but also to curiously observe the political turmoil that had emerged since the creation of a constitutional government through military revolt in 1820. Reflecting on this excursion in a later travel memoir, Porchester recalled arriving in Spain that year during a time when “the country was distracted by civil dissensions” (163). A revolt in support of the absolutist King Ferdinand VII—against the constitutional regime—was anticipated, but none had yet occurred. Porchester noted that “the exasperation of feeling throughout the disaffected provinces was extreme; the royalists were everywhere in a state of active though secret preparation, and were only waiting for the countenance of foreign powers to commence the struggle” (163).

These particular recollections, published during the next decade while the Carlist War (1833-1840) cleaved Spanish society into constitutional and reactionary factions, reveal the extent of his familiarity with the contours of Spanish political activity. Upon entering Spain, Porchester possessed no forthright attraction to either the constitutionalist or royalist party, yet (as a good English aristocrat) he claimed to believe in the good of liberal and representative governance. He was, however, moved by the feelings of disaffectedness experienced by the Spanish royalists and horrified by the attacks on both clergy and nobility. Regarding King Ferdinand himself, he was disappointed that the monarch had become a deadweight within a novel constitutional regime, confined to his palace and waiting for a royalist revolution. These experiences spurred Porchester to put pen to paper, resulting in the 1825 publication of The Moor.

Most importantly, this work includes an extensive preface that effectively serves as a manifesto of Porchester’s political opinions regarding continental politics, specifically constitutionalism and liberalism. While he had indeed written a narrative poem about Spain’s historic Granada War (1482-1491), nearly three quarters of the preface’s eighty-four pages concern “the present state of Spain” (xxiv). For example, to justify the inclusion of a band of Catalan guerillas within his poem, Porchester admits anachronism and explains that they are based on the same royalist guerillas who had captured him in Montserrat in 1822.

Reflecting on this experience, Porchester indeed associates these royalists with the general evils of absolutism and despotism: “Had success attended their arms, they would probably have re-established that worst of evils—absolute government, which, indeed, they effected sixteen months later, in conjunction with the French armies,” referring to the re-establishment of absolutism under King Ferdinand in 1823, with the help of 100,000 French troops (xxvi). Importantly, however, Porchester presents this absolutism as reactionary in the plainest sense, a perhaps-understandable outburst against the failures of the constitutional government:

Still I have little doubt that had they [the royalists] been subjected to more delicate management, had their prejudices been treated more leniently, and national and provincial feeling more respected, all the zeal and perseverance which they displayed in supporting the cause of arbitrary power would have been devoted to the defence of the constitutional monarchy. (xxvi-xxvii)

Porchester affirms the necessity of a government both aware of and, more importantly, respectful of public prejudice and national feeling: “Unfortunately a series of hasty and impolitic acts on the part of the Cortes exasperated public feeling, and paved the way for the entrance of the French armies” (xxvii).

Interestingly, Porchester argues that the government’s inability to manage and respond to “public feeling” was itself a constitutional problem. The Constitution of Cadiz excluded a great number of “landed proprietors, the clergy, a party in the cities, and an immense numerical majority in the provinces” from its legislative institutions. Choosing “principles of democracy” as the basis for representation, rather than “a state of property held under tenures of the most aristocratic character,” resulted in “a fatal conflict of interests” (xxviii). The Spanish constitution was deficient in that it “attempted to combine the form of monarchy with institutions essentially republican; —an anomalous mixture by no means easy to maintain” (xxxiv).

Porchester characterizes this new regime as innovative and ultimately revolutionary: the agricultural class found their livelihoods dependent on whatever measures the constitutionalists decided to propose and pursue, convents and religious institutions were suppressed, and provincial privileges and geographical divisions were completely reconfigured (lxx-lxxii). This last measure, described as “a measure offensive in the last degree to the entire peasantry; a measure uncalled for by any political expediency, that has been little known out of Spain, and whose practical ill effects have been still less understood,” was particularly odious to the author (lxxii). “The reasons alleged for the subdivision of the provinces were grounded on the inconvenience arising from their unequal distribution,” the author admits, “but probably the secret motive of that determination arose from a belief, that by confounding ancient limits and breaking down former attachments, they would more rapidly obliterate the memory of the old regime” (lxxiv).

Despite all these criticisms of the Spanish constitutional regime, Porchester still, puzzlingly, believed in some inherent good attached to liberal government. The immediate problem was not some idea of constitutional or representative government, as these were in theory good. Rather, Porchester critiqued specifically the immediate recasting of society attempted by the Constitution of Cadiz. A written constitution could potentially ensure liberty, he maintained, and looked towards neighboring Portugal as evidence of such. In 1830, for instance, when Portugal’s Constitutional Charter of 1826 became the target of dissatisfied reactionaries, Porchester wrote in its defense, calling it a document “rational in its enactments, just in its distribution of powers, and compatible with existing institutions, which it tended to reform, but not to subvert.” This Portuguese constitution contrasted starkly with that of 1820, which, according to Porchester, “was wholly opposed to the feelings of the country, and could only have maintained itself by effecting a revolution, not solely in the general disposition of the property, but in the habits and opinions of all classes of society” (1-2).

Ultimately, though, as civil war between constitutionalists and reactionaries began to plague both Spain and Portugal throughout the 1830s, Porchester became more plainly reactionary. The second volume of his aforementioned travel memoir offered an appraisal of the counter-revolutionary Carlist movement as one committed to the defense of national liberty embodied in Carlos, the reactionary pretender to the Spanish throne. The existing social and political order, understood as an organic product of historical development and national character, would ensure liberty, the argument went—not a novel constitution (chapter 8).

Resultingly, due to perceived constitutional failure in both Spain and Portugal, Porchester would ultimately eschew written constitutionalism in toto. In doing so, he separated himself from those in Britain who believed in supporting any constitutional regime as a safeguard against both further revolution and regressive absolutism (this support being either ideological, as Bentham’s was, or practical, such as that of Lord Palmerston). Attaching his anxieties about Europe’s political future to those of Spain’s reactionary royalists, Porchester maintained that constitutions themselves—which, to restate, would “obliterate the memory of the Old Regime”—were the revolution.

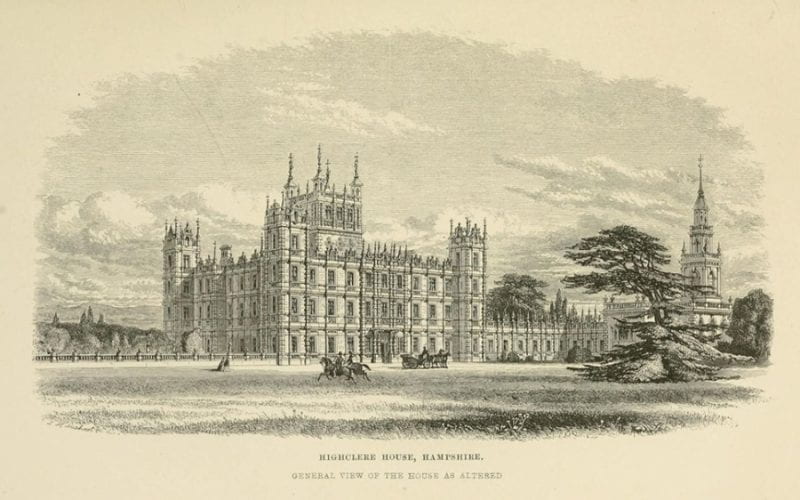

Joseph Puchner is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at Princeton University, studying the political history of nineteenth-century Europe. He is currently researching the establishment of constitutional regimes in Spain and Portugal during the first half of the nineteenth century, and in particular the centrality of such developments to the elaboration of transnational reactionary political networks across Europe. He maintains secondary interests in the English country house and the family history of the Carnarvons of Highclere.

Featured Image: A sketch of a proposed renovation for Porchester’s Highclere estate (from The Life and Works of Sir Charles Barry, by Alfred Barry, 1867). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.