By Jonathon Catlin

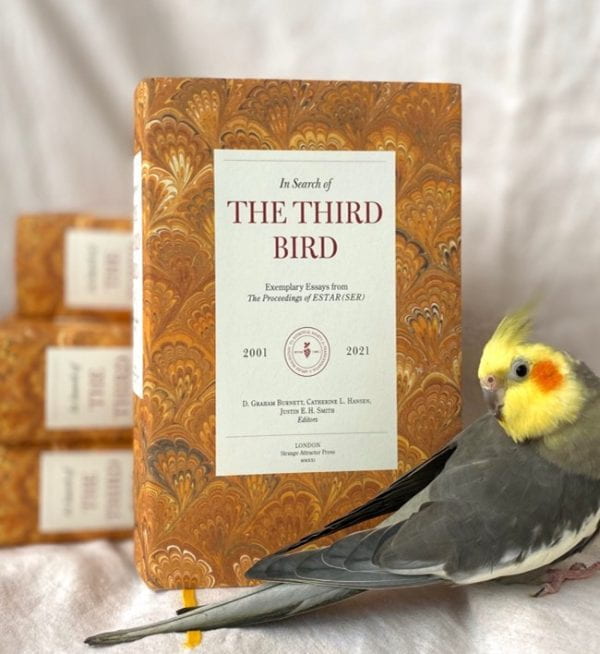

Three leading scholars of the historical imagination, D. Graham Burnett (History of Science, Princeton University), Catherine L. Hansen (Comparative Literature, The University of Tokyo), and Justin E. H. Smith (Philosophy, University of Paris 7), recently published an unusual co-edited volume, In Search of The Third Bird: Exemplary Essays from The Proceedings of ESTAR(SER), 2001–2021 (Strange Attractor Press, 2021). This “very strange book” (Hal Foster) is at once history and fiction, scholarship and a poetic archive of performance art centered on cultivating practices of attention. Contributing editor Jonathon Catlin interviewed Burnett about this weighty (at nearly 800 pages) experiment in historical thinking and writing, and what lessons it might offer for a discipline in an identity crisis in the age of “post-truth” —and a world seemingly plagued by a deficit of attention in the age of social media.

Jonathon Catlin: In Search of the Third Bird purports to be a contribution to the history of the so-called “Order of the Third Bird” conducted by an association known as ESTAR(SER), “The Esthetical Society for Transcendental and Applied Realization,” aka “The Society for Esthetic Realizers.” In his (exhilaratingly negative!) reader’s report on the volume, the intellectual historian Darrin M. McMahon writes that ESTAR(SER) “would seem to associate itself with the history of aesthetics, in a general sense, and with problems of ‘practical aesthesis’ more specifically—which is to say, with the cognitive and embodied work of experiencing what can be experienced.” Despite the acronym “ESTAR” playing on the Spanish for “to exist,” it is difficult to say in what sense the association (ESTAR[SER]) and its ostensible “object” (the “Birds”) really do “exist.” McMahon notes numerous “peculiarities, anomalies, and antinomies” in this “deranged” volume, which appears to reprint a set of essays from an obscure journal, the Proceedings of ESTAR(SER). Indeed, McMahon expresses “serious doubts about the ‘historicity’ of this journal” itself, not to mention the substance of the essays. In another negative report, Benjamin Breen calls the book “a frappé of falsehoods,” which he goes on to enumerate in considerable detail. How and why, in your account, did this volume emerge?

D. Graham Burnett: In Search of the Third Bird emerged out of more than a decade of really intense and special collaboration among several dozen artists, historians, and creative makers of different sorts. I think everyone involved in the project would offer their own accounts of how they came to the project, and what that work has been “about” for them. Including Darrin and Ben, and Jimena Canales, whose brilliant “negative peer-reviews” are meant to function as a kind of slap-down vade mecum for the book—in high academic style. They are meant to “orient” the reader to some of what is going on in those dense pages. For me, the joy and intimacy of intellectual/imaginative collaboration has been a major feature of making the book, and of the field of thought it represents. Friendship in the spaces of inquiry feels like a rare gift, and I think this book is both about that, and, I hope, reflects it.

JC: I think I have a sense of what you are getting at, although, for readers who have not picked up the book, we have to make sure they understand that it is a heavily-footnoted scholarly tome, one that presents some sixteen or seventeen very academic-looking essays. There are nearly five hundred works listed in the bibliography, in eight or nine languages. Friendship?

DGB: Fair enough! What strange things we do, with and for our friends!

JC: And maybe that is what the book is about?

DGB: It is certainly true that the subject of the book, the “Birds,” can be understood as a kind of trans-historical community of friends. ESTAR(SER) is a research collective that exists to study the Avis Tertia, or “The Order of the Third Bird.” Who or what is that? Well, those “Birdish persons,” as we reconstruct the story, are a sort of invisible presence across time, an eccentric cohort of passionate devotees of “joint attention” who have gathered in various times and places to attend, together, to the stuff of the world: paintings, sculptures, rocks, bridges, bodies of water—even, sometimes, empty space. They make themselves present to the world in focused occasions of experiential duration. They seem to enjoy it. And they seem to take it seriously. But in their histrionic ways, they also seem to be playing at the same time. It would appear that they think their work of giving attention, together, amounts to a kind of collaborative world-making. Or a poetics of being? If Fourier had been right about the “armies of love,” their lead squads might have looked something like the Birds.

JC: Studying attention has gained tremendous popular traction in recent years, from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow to Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus. And attention is obviously a keyword for all of you. I see that you also just co-edited a book entitled Twelve Theses on Attention (Princeton, 2022). ESTAR(SER) studies the “Birds,” but what the Birds do, it appears, is basically just “pay attention” to stuff—if in slightly peculiar or intense ways. In that sense, ESTAR(SER) sometimes claims to be engaged in “the specific historicity of attention” or to be doing research into “how attention has been ‘paid’ in different times and places, for different purposes, and with different effects.” McMahon even goes so far as to propose “Attendere Aude—Dare to Attend!” as the book’s battle cry. Could you say more about how the project engages with the so obviously weakened “attention economy” of the distracted present?

DGB: Attention is, in many ways, central to the book, and also to the larger project of which the book is a part. Because the ESTAR(SER) collective, however Borgesian, very much exists! We were part of the 2018 São Paulo Biennial (an important contemporary art event in Brazil), and over the years we have done performance pieces and installations at lots of different institutions: at Manifesta (in Zurich in 2016), the Palais de Tokyo (in Paris in 2014), MoMA PS1 (here in NYC, also in 2014). We have a large exhibition coming up at the Frye Museum in Seattle later this year, and a current show at the Monira Foundation in Jersey City. In our text-based practices (like In Search of the Third Bird) and in our participatory and performance-based work, we are always trying to “draw attention to attention”—to invite people to explore the ways that practices of attention are substantially constitutive of individual and collective life. All of us very definitely think of that work as “political,” in the broadest sense: the hyper-intensified commodification of attention represents, in my view, a principle threat to human flourishing in our time. The intricate work of ESTAR(SER), however, is hardly “on the barricades” on this issue in any obvious way. For all its earnest concern with attention, ESTAR(SER) is also preoccupied with some highly specialized problems of historical knowledge, and In Search of the Third Bird is a contribution to the relatively obscure literary genre of “historiographic metafiction.” Working at the intersection of artistic and research practices, ESTAR(SER) cares about the future of the universitarian “humanities,” and about artists like Jim Shaw and Walid Raad and Alison S. M. Kobayashi. None of this is going to directly protect anyone from the almighty vampire squid of surveillance capitalism—repeatedly “jamming its blood-siphon into the face of humanity” as we speak. That said, many of the folks involved with ESTAR(SER) do work on that problem in more direct ways, for instance through the work of the Friends of Attention, a more “activist” group that authored the “Twelve Theses on Attention.”

(Photo courtesy of Zachary Hoos)

JC: Let’s stay with those specialized problems of historical knowledge for a bit. In Search of the Third Bird presents, to a casual eye-scan, as a learned work of history. Though in some basic and important ways, it definitely isn’t. For starters, some of the things it treats “historically” are not “real.” They didn’t happen. Similarly, some of the works it cites don’t exist. The archival sources on which much of it is based have highly suspect provenances. You have yourself called the book a work of “historiographic metafiction” (a term coined by the literary theorist Linda Hutcheon back in the 1980s). What is going on? In his “peer review” McMahon suggests that your work implicitly offers a kind of “constructivist” theory of history: “The evidence, presumably, is out there waiting to be discovered (if it already exists), or created (if it does not), and so ‘brought into being’ in the act of retrieval.” The “scholars of ESTAR(SER),” he writes, “recognize, and at times would appear willfully to embrace, the more imaginative side of historical inquiry and recovery.” In what sense does the past “exist,” according to the more expansive and playful conception of history the volume seems to pursue?

DGB: The past very definitely “exists.” Or “existed,” anyway. And much about it can be known and recovered. This is the work of history. I trained as a historian, and I “do” history. In fact, I’m most of the way through writing a pretty conventional “history” of the scientific study of attention from 1880 to 1980, and I very much “believe” in the traditional work of archival historical research. I teach the field and care about it deeply. That said, it is absolutely true that In Search of the Third Bird is not a conventional history. But it’s not a straight-forward “fiction” either. Nor is it, in my view, any sort of post-modern “fake news” about the past, or insouciant jouissance des clercs, historiographically-speaking. There are several things to say, I think, about what the book “does.” But ultimately it will be up to its readers to decide what it achieves—and what it fails to achieve. I can try to say a few things; others who contributed to it would, I am sure, say other things—and they might be more correct.

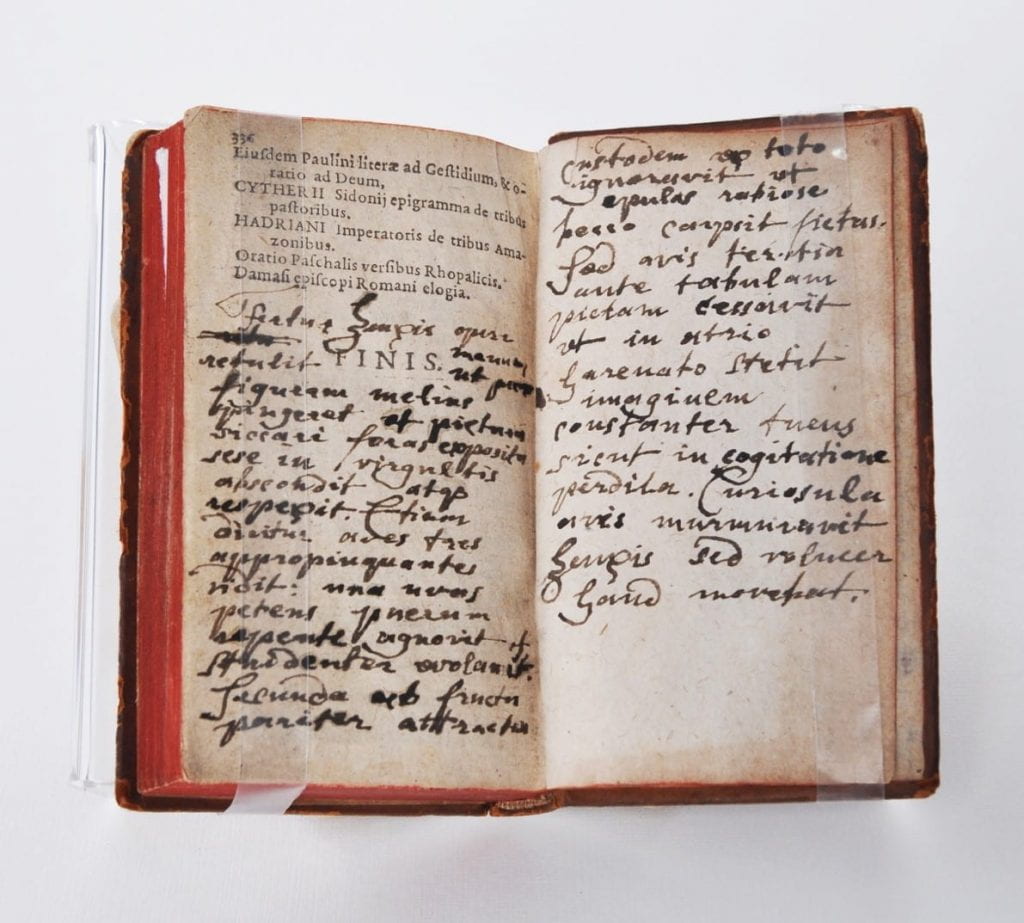

JC: The book certainly defies easy categorization, but it clearly engages (while to some extent blurring) history and fiction, science and art. We once read together the writings of W. G. Sebald, whose own self-proclaimed method of “documentary fiction” combined thorough archival research with totally invented sources (often reproduced in photographs in his books)—a way of at once emphasizing the pastness of the past (through loss), and also the ways it haunts the present. ESTAR(SER) works, it seems, from a similarly unstable dream-archive that is in constant flux (and may not even exist). All this leads McMahon to provocatively term your process “gnostic historiography.” Does fiction fill the gaps in history, or simply help us experience it? In what sense do history and art reach for the same kind of “eternal” or “beyond”?

(reproduced from In Search of the Third Bird)

DGB: That is a beautiful question. Exactly the kind of question In Search of the Third Bird wants to raise, I think. Embedded in what you are asking, and I know you know this, is really all of it: Kant, Hegel, Dilthey, Heidegger, Gadamer, the “Crisis of Historicism”—the effort to establish the critical basis and/or epistemic foundation of historical knowledge; and the complex way that history as such has proven a solvent of metaphysics, even as the temporality posited by historicism keeps returning as a new kind of (illegitimate?) metaphysical ground. This really is the heartland of this book as an effort to “think history.” These are the problems it “circles”—or, to adopt a “Birdish” posture, before which it stands, attentively. What did Hayden White say at the end of Metahistory? The task, as he saw it, was to ensure that “historical consciousness” can “stand open to the re-establishment of its links with the great poetic, scientific, and philosophical concerns which inspired the classic practitioners and theorists of its golden age in the nineteenth century.” He said the same thing at the start of the book too. He meant it! His aim, as he repeats several times, was to write an “ironic” history of the way the discipline of history slumped into a pervasively ironic mode: believing neither in its status as art, nor its status as a science; but adventitiously (if not cynically) invoking whichever claim permitted one to get by as a courtier in whatever court happened to provide opportunities for advancement. He hoped that by ironizing the ironic condition—by using irony against itself—he might…what? Emancipate academic history from its dogmatic slumbers? Something like that. Though I don’t think he thought everyone was asleep in the same way. And he was too subtle a thinker to believe that the truth was going to make anyone “free” in any get-out-of-jail-free sense.

JC: So, is In Search of the Third Bird “ironic”? The volume is certainly quite funny. While reading it, I kept wondering to myself why exactly that was. Is “Birds ‘Birding’” a parody of the nineteenth-century Rankean and scientistic historical guild? Does “Bird-history” poke fun at the present state of the historical discipline? How do these essays balance the utter sincerity of care and attention with irreverence and play?

DGB: Ah, I do hope readers can see and feel this sense of play. Yes, it is supposed to be funny—or parts of it, anyway. There is a whole essay in the book that looks directly at the nonce-Kantian idea that “gelastics” (the study of the joke) might actually merit treatment as a kind of “first philosophy.” And the book is certainly constructed as a kind of “game.” But is it ironic? Everything would depend on how that is meant. Is Metahistory “ironic”? White says it is. Does this mean, using his definition of irony, that it “says the opposite of what it means”? Maybe. But it “means” many things, so it would take a good deal of work to sort out what is going on. Reasonable people could disagree. And that is the point! Because, in the process, interpretive understanding would happen. And that, I would suggest, is how Metahistory succeeds in opening a way “out” of the predicament of disciplinary history as White saw it: the kind of truth he points toward in the book cannot be accessed in a scientistic way; it will not yield to “method”; it will only happen, in time, as a result of dialogue, which requires time and care and attention (but which certainly needn’t be dour).

JC: Is this what you want for In Search of the Third Bird? Your invocation of the “truth” that won’t happen via “method” puts me in the mind of the twentieth-century German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. The formulation is, in a basic way, his. Truth and Method has been, I think, important to you—perhaps passed down through your training with Cornel West, who knew Gadamer in some capacity. In an epigraph to In Search of the Third Bird, Gadamer claims that “the basic movement of spirit” is “to recognize one’s own in the alien, to become at home in it.” Is this what the book is “about”?

DGB: For me, yes. Although it is important to get the other half of the sentence in there: Gadamer finishes by contending that the “being” of spirit “consists only in returning to itself from what is other.” This is a concise statement of “Birdish” practice. Birds use attention to leave themselves, and to return to themselves. They use language to return to each other. This book documents that form of life. At stake is the concept of “experience,” the absent presence in historicism, and the hobgoblin of “critical” historiography (e.g., Joan Scott’s “The Evidence of Experience” [1991]). Can “experience” be treated historically? Martin Jay’s Songs of Experience (2005) goes at the problem one way. ESTAR(SER)’s way could not be more different. But it might be more “true” to experience as a genuinely historical problem. The book asks its readers to confront this provocation, even as the volume points away from confrontation itself. We sometimes like to joke that the book wants to be the finger in the adage about the sage pointing at the moon: does the fool look at the finger? Well, what’s to see there? Hmm. Let’s look!

JC: You have taught seminars with Jeff Dolven on the concept of “experience” as well as on “The Poetics of History.” Both seem relevant to this book, to which Dolven also contributed. And you and Justin E. H. Smith, one of your co-editors, ran the Princeton History of Science Workshop last year on “Attention” as a historical, philosophical, and scientific problem—another topic on which you teach. In Search of the Third Bird seems to have arisen from this nexus of archival poetics, the problem of experience, and the historicization of attention. Is there a special relationship between history and attention? Between the archive and experience?

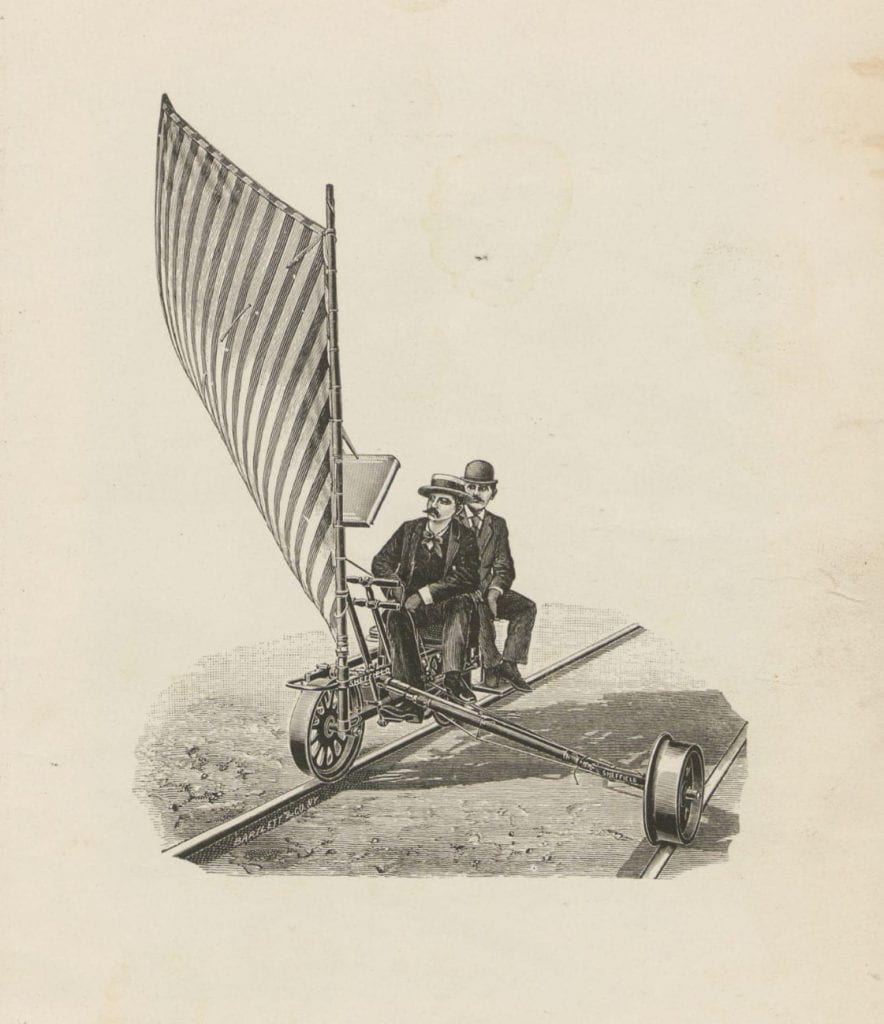

(Reproduced courtesy of ESTAR(SER)’s Communiqués)

DGB: At the beginning of his classic That Noble Dream (1988), Peter Novick drops a memorable footnote to a paper delivered at the American Historical Association in 1971 by a young historian named James B. Parsons, apparently entitled “The Psychedelic Approach”—meaning, the psychedelic approach to history. The project never went anywhere, it would seem, and though I made some small efforts, I have never been able to track it down. But the kicker of it is that Novick rather puckishly contends that Parsons may have been closer to Ranke’s real concept of historical inquiry than any of the plodding empiricists who later claimed him. I don’t especially have a horse in that race. Nor do I have strong feelings about a Collingwood-style account of history as the “re-enactment of past experience.” Justin E. H. Smith and I have together (with others) written our own kind of “Psychedelic Approach” to history, the “Corona of Care,” and it links attention and the past very closely—in a way that can be, in a performative setting, very affecting. This work is very much ESTAR(SER) work: the “presencing” of absent presences. Is it fair to say that this is “impossible” work? Yes. It is, in some sense, impossible. And yet it also happens. We know that it can happen. History is this. A mystery? A mystification? Both. Yes. Tenderly we sift the former from the latter.

JC: Is there anything else you’d like people to know about In Search of the Third Bird?

DGB: Well, I do think that the book is gesturing at something. And that is part of its game-like architecture. I am reminded of John T. Irwin’s great, mad masterwork, The Mystery to a Solution (1994). Irwin’s writings on Poe and Borges were participatory. Irwin was a critic, but he was also a poet, and his readings both unravel and “weave.” They are contaminated by their subject, and this both constitutes their authority, and, in a fascinating way, vitiates it. That instability is the instability of a reel, of a dance. It is the exquisite superposition of knowledge and understanding—which cannot “settle.” Our book is “tainted” in this way, it wants the play of illnx, dizziness, not just games of mimicry or chess-like machinations. It is the case that In Search of the Third Bird is a book designed to be read by a process of filtration, or restabilization. The book is intended as a “superposition” of literature and history. How it is “read” is a result of how it is read: for instance, if one Googles around (to sort out what is real and what is not) one learns a bunch of history; what is left is the novel.

JC: So, is the work, in the end, a roman à clef?

DGB: What does Wallace Stevens say? “I was of three minds, / Like a tree / In which there are three blackbirds.”

JC: I see these bumper stickers now that say “Birds aren’t real.” Any clue there?

DGB: None whatsoever!

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University. His dissertation is a conceptual history of catastrophe in modern European thought, focusing on German-Jewish intellectuals including the Frankfurt School of critical theory. He tweets @planetdenken.

Featured Image: In Search of the Third Bird.