By Franziska Hermes

In 1783, Frances Chambers wrote a letter from Bengal to a friend, worrying that “there is no news of the Grosvenor at St Helena & the Valentine & 3 other ships arrived safe in England I am very unhappy about it” [1]. Chambers was interested in the journey of the Grosvenor, an East Indiaman sailing ship that had left India the previous year, for one specific reason: One of its passengers was her seven-year-old son Thomas, whose father was Sir Robert Chambers (1737–1803), an influential judge in the service of the British East India Company, which ruled India at the time. Frances Chambers was unaware of the ship’s fate when she posted her letter, but she had been right to worry.

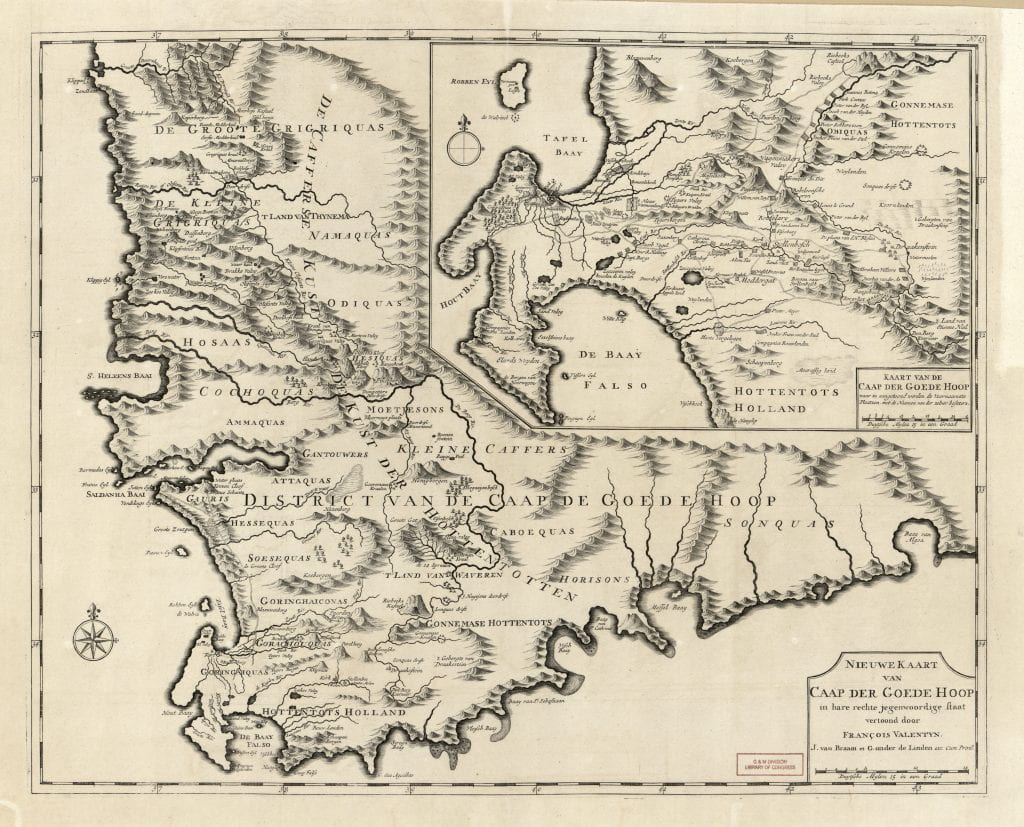

Unlike the Valentine, another East Indiaman, the Grosvenor was never to arrive in London, as the ship had been lost in August 1782. Most of the passengers and crew were able to leave the sinking ship alive, but they were wrecked on what is now Pondoland in South Africa. What followed was thus a trek of several months, fuelled by hopes to find European settlers and made almost unbearable by harsh terrain, hunger, thirst, wild animals, and frequent encounters with Indigenous peoples. In the end, out of 140 men, women, and children only 19 survivors reached the Cape of Good Hope, then governed by the Dutch East India Company (Fig. 1), a vast multi-national trading and shipping company. Little Thomas Chambers, sent to England for education, was never to be seen again.

The Grosvenor makes for a unique keyhole through which to explore the history of mobility within the eighteenth-century British Empire. As John-Paul Ghobrial has recently proposed, ships and people on the move are important for mobility studies, because their narratives are “moving stories [that] can reveal new geographies we do not see otherwise.” The same is true of lost ships, but there is a key difference. The geographies of wrecked ships were as new to contemporaries as they are to historians today. I argue that this is the case because stories of lost ships are stories of movement gone wrong rather than “moving stories.” By definition, shipwreck includes a moment of chance, as the Grosvenor demonstrates.

A British vessel left India on its way to England, only to be lost on the South African coast—at that time outside the reach of the British Empire. Ships could also be lost on the British coast, such as the Halsewell, an East Indiaman on its way to India, which was wrecked in 1786 (featured image). In case of the Grosvenor, however, suffering shipwreck at the South African coast forced castaways and people otherwise affected by the wreck to find creative solutions to a problem they had neither anticipated nor planned for. As a result, shipwreck was not the end of the Grosvenor’s journey. It was rather the beginning of new contacts and connections across the British Empire. By following shipwreck stories, as I demonstrate in this piece, one can thus arrive at new geographies of mobility.

When looking at shipwreck geographies, the starting point is the spot where a ship was lost (Fig. 2). Both the natural environment and geopolitical contexts of this spot determined the survival rate of the people on board of wrecked ships. After all, wars between European powers also extended to regions outside Europe. This means that castaways frequently found themselves at the mercy of political enemies. On paper, the situation was similarly daunting for the Grosvenor passengers.

In 1780, Britain had declared war on the Dutch Republic, the fourth in a series of Anglo-Dutch wars, which would last until 1784. Although the survivors that reached the Dutch settlements were in principle British prisoners of war, Dutch Governor Joachim van Plettenberg “did not hesitate a Moment” to send out rescue parties to search for more survivors, as he assured British Governor Warren Hastings in a letter written to Bengal in March 1783 [2]. Learning of the search parties, Hastings purchased a valuable diamond ring and sent it as a gift to the Cape in March 1784. On the ring, there was an engraved quotation from Ovid’s Metamorphoses that can be loosely translated as “it is right to be taught, even by an enemy” (the original passage reads “fas est et ab hoste doceri”).

Looking at the Cape of Good Hope from a Eurocentric perspective, this episode is surprising, as both van Plettenberg and Hastings’s actions stood in contrast to national policies. Yet such a conclusion is based on the false assumption that the European East India Companies were exclusively “national” spaces. Although there were phases of fierce competition between British and Dutch companies, Anglo-Dutch rivalries in Europe did not strictly apply to the East or—in this case—the Cape. Historians have shown that both companies, irrespective of national interests, regularly worked together to pursue their own private fortunes.

In the specific case of the Grosvenor, empathy might have brought the shipwrecked Britons and Dutch even closer together at the Cape. Members of both companies knew the hardships that came with long-distance travel by ship. They also feared encounters with the Indigenous peoples of South Africa, which van Plettenberg, in his letter to Hastings, characterized as “savage Nation[s], to whom the Principles of Humanity are little known” [3]. These shared experiences united the British and the Dutch, as they allowed for a sense of familiarity between “national strangers” to borrow a phrase coined by Francesca Trivellato.

Let us, however, not overly romanticize this familiarity between “national strangers”—it did not create a genuinely cosmopolitan community abroad. Solidarity was highly exclusive: The Grosvenor’s sailors of Indian origin, known as “lascars,” were rarely included in British comments on the wreck; and if they were, they were “strongly suspected of neglecting, if not maltreating, their fellow Sufferers” [4]. This was a baseless claim, possibly voiced because far more Indians survived the shipwreck than Europeans.

Taken together with the dehumanizing statements directed at the South African Indigenous peoples, the Anglo-Dutch familiarity we see at the Cape is best characterized as a shared white imperial experience. The Grosvenor’s story reveals that categories of belonging in early modern mobility were fluid. Accordingly, the idea of foreignness was, as John-Paul Ghobrial argued, “ultimately a local affair. Belonging or unbelonging, native or alien, local or stranger: these were conditions that were decided […] by local actors using local processes of identification.”

It should come as no surprise that we encounter these imperial processes in the Cape of all places. Although officially occupied by the Dutch in 1652, the colony had remained an important point in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean shipping systems as a refreshment post. A meeting point of two oceans, the Cape served as a space of social, economic, and cultural exchange in the eighteenth century (Fig. 3). A glimpse into the power dynamics of this diverse environment can be found in various letters of early modern British travelers who regularly entered the Cape on their journeys in the British Empire. Due to the spread of news in Britain and beyond, they were aware of the fate of the Grosvenor and its passengers, most of whom were lost without a trace. Travelers thus often used their stays at the Cape, which could extend to weeks, as “an opportunity of being acquainted” with locals who promised to provide them with the latest news on the fate of these lost people [5].

One of these locals was Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon (1743–1795), a Dutch commander who was stationed at the Cape (Fig. 4), and a keen explorer whom contemporaries recognized as “a man of much information” [6]. An authority on ethnographic and geographical knowledge of southern Africa, Gordon was widely known and trusted. In letters, diaries, and other surviving documents of the British Empire, he often appears in the role of a mediator. Although he was ultimately unable to bring back Thomas Chambers and other passengers of the Grosvenor, relatives such as the Chambers family still held on to the information passed on to them by British travelers. They found comfort in Gordon’s vigorous support for relief missions, and his reassurance that their loved ones had died with certainty—rather than being subjected to prolonged suffering at the hand of Indigenous peoples. Gordon’s work and reputation are thus a testament both to the circulation of knowledge facilitated by the environment of the Cape and the urgency for such information exchange in the context of shipwreck.

While shipwreck usually marked the end of a ship’s physical movement, it did not mark the end of mobility altogether, as the case of the Grosvenor reveals. Due to its accidental nature, shipwreck put pressure on contemporaries to react and, if necessary, resort to extraordinary measures. The loss of the Grosvenor prompted Britons and East India Company members all over the British Empire to reach out to their contacts at the Cape. It also encouraged Joachim van Plettenberg to provide the Grosvenor’s passengers with help “[a]ltho’ War reigned between us” [7]. During the aftermath of the shipwreck, Gordon and other knowledge brokers exchanged intelligence in transnational information channels, while encounters with multiple nationalities at the Cape had contemporaries reflect on their group identities. Despite being a failed voyage, the Grosvenor eventually led to an increased mobility of people, letters, and ideas.

Eighteenth-century shipwrecks reveal the workings of empire both on macro and micro levels. Leaving a trace in historical documents, shipwrecks can make visible networks of knowledge exchange which would have remained invisible, if the ships had reached their destination. For intellectual historians, starting out from a specific wreck can be a productive method to grasp larger geopolitical processes which are brought to our attention through these singular catastrophes. The Grosvenor turned the spotlight on the fact that Britons in transit experienced empire completely differently than those not on the move. They had access to transnational networks, encountered more fluid categories of belonging, and actively cooperated with the supposed Dutch “enemy” at the Cape, while their home country was at war.

Yet the Grosvenor also shows that there were darker aspects to these imperial processes. The hostile accusation that the Indian sailors had maltreated their European fellows, for instance, implies racialized anxiety. It could have been triggered by the fact that both the loss of the Grosvenor and global integration more generally had disrupted hierarchies essential to shipboard organization and colonial life. Early modern shipwreck brought contemporaries face to face with the challenges involved in processes of doing empire. It promises to do the same for intellectual historians, if only we are willing to follow the clues left behind.

[1] British Library Mss Eur E4, 445-446.

[2] British Library IOR/P/2/63, 538.

[3] British Library IOR/P/2/63, 537-538.

[4] National Maritime Museum AGC/H/23, 3.

[5] National Maritime Museum AGC/H/23, 1.

[6] National Maritime Museum AGC/H/23, 1.

[7] British Library IOR/P/2/63, 538.

Franziska Hermes is a doctoral fellow at the Global Intellectual History Graduate School of the Freie Universität Berlin. Her research interests are the eighteenth-century British Empire and its maritime history, with a particular focus on shipwrecked East India Company vessels. She is currently a research fellow at the German Historical Institute London.

Edited by Philippe Schmid

Featured Image: The wreck of the East India Company’s Halsewell (1786) by Robert Smirke. This print shows the Halsewell East Indiaman which was wrecked four years after the Grosvenor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.