Tomás Valle is a PhD candidate at the University of Notre Dame. He is currently on a two-year research stay at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, funded by the German-American Fulbright Commission, the DAAD, and the HAB’s Rolf und Ursula Schneider-Stiftung. He specializes in the intellectual cultures of Lutheran universities in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and his dissertation studies post-Reformation humanism through the life and scholarship of Johannes Caselius (1533–1613).

He spoke with contributing editor Jacob Saliba about his essay “Eilhard Lubin, Academic Unorthodoxy, and the Dynamics of Confessional Intellectual Cultures,” in JHI (83.2).

***

Jacob Saliba: Your article discusses the emergence of a certain kind of post-Reformation theology espoused by the Lutheran professor Eilhard Lubin in late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Germany. Your narrative begins in 1596 when Lubin published Phosphorus, a theological treatise about the origin of evil (i.e., sin), the causative power of God, and the relationship between the two. In it, Lubin does not so much suggest that the source of evil in humanity may in part be due to God, but rather that this formulation requires reevaluation in order to offset assumptions that God is responsible for evil. In simple terms, what was his thesis about God and the origin of evil?

Tomás Valle: A primary goal of Phosphorus is to attack the idea that God might be responsible for sin. The problem is that Lubin does such a spectacularly poor job! His argument makes evil in some sense metaphysically (or physically—the line is blurry) necessary in created things: everything is created out of nothing or non-being, which is equated with evil, but that evil/nothingness (also equated with prime matter!) remains in created things, which gives them an inherent inclination back towards evil/non-being. Lubin also sometimes uses semi-active language for God’s role, such as saying that God “leaves” this inclination in created things. So, there are all kinds of problems in Lubin’s account of theodicy (and creatio ex nihilo, which is the other point he sets out to defend).

JS: Lubin’s Phosphorus was condemned in 1604 (by Albert Grawer), and even so, his home-institution in Rostock supported him as he prevailed against the accusations, further solidifying a positive reputation within Lutheran culture. As you show, this eight-year period of acceptance followed by a successfully performed counter-argument demonstrates a unique phenomenon in the post-Reformation era: theologians could make non-traditional—borderline heretical—arguments without repercussions and while resourcefully self-presenting an orthodox commitment to tradition. You call this type of thinking unorthodox, rather than heterodox, for its capacity to rework inherited traditions while still accepting the perennial character of tradition itself. Could you discuss these two categories of “unorthodox” and “heterodox” in more detail, and why they matter in this regard?

TV: In suggesting “unorthodoxy” as a heuristic, I want to help historians appreciate the diversity and flexibility of confessional intellectual cultures in early modernity. Calling early modern figures “heterodox” in relation to the surrounding society is often the historian’s retrospective, normative judgment about their private beliefs, which doesn’t reveal much to us about the culture they inhabited, and in fact reinforces the (self-)image of orthodoxy as unified and universal. This has all sorts of problematic consequences for how we narrate early modernity, making it a story of “the orthodox” vs. “the heterodox,” in which the latter look more and more like secular moderns. Figures who don’t fit this narrative get either assimilated to one of the sides or swept under the rug. Of course, lots of other scholars have critiqued and are critiquing this way of approaching early modernity, but I think a terminological shift would be useful.

I like the term “unorthodox” because it can range on an evaluative spectrum from “problematic” to simply “weird” or “unusual.” In this way, it can convey a wide variety of contemporary attitudes, and part of my point is to bring our analysis of past thinkers into closer conversation with the audiences for whom they wrote and spoke. (While not an actor’s category, then, I think “unorthodoxy” can reveal more about a thinker’s relationship to the surrounding culture than “heterodoxy.”) “Unorthodoxy” also has something undefinable about it: it’s not obviously “other” (“hetero-”). Thus it resists both the early modern polemical urge to label one’s opponents and the modern historian’s desire to create clear through lines to the present, both of which end up misrepresenting past actors. Instead, “unorthodox” highlights the ambiguities and divergent views that existed within “orthodox” confessional cultures and the internal tensions that these caused. I think that the more we understand those multipolar tensions—rather than an imagined binary—the better we’ll be able to comprehend the dynamics of cultural and intellectual change in early modernity.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting adding “unorthodox” to a taxonomy of early modern opinions, such that some people would be “orthodox,” others “unorthodox,” and others “heterodox.” My goal is not to classify thinkers but to reveal the flexibility of orthodoxy itself in a culture where there are diverging opinions as to what constitutes “orthodoxy”—which is essentially any culture. In Lubin’s case, I argue, he himself and his local community at Rostock University considered his writings “orthodox,” while his antagonist Grawer tried to paint him as “heterodox” (in this case, “Calvinist”), and Lubin defended himself to a wider audience of theologians by claiming his writings were “unorthodox”—problematic, yes, but not deserving the charge of heterodoxy—and hence preserving his reputation as “orthodox.” So, I want us to reflect on how these terms can work together and apply to the same person, which forces us to sideline our own evaluative perspective to some degree and focus on the cultural situatedness of knowledge production and knowledge dissemination in early modernity. In this way “unorthodoxy” is both a pars destruens for binary thinking about intellectual difference and a pars construens for a more culturally embedded intellectual history.

JS: You say that understanding this type of thought as unorthodox requires an attention to “boundary-work” as a framework. How would you define “boundary-work” and in what ways did it prove crucial to your article’s approach?

TV: The concept of boundary-work was developed in the sociology of science and has been applied to early modern science, but I think it deserves much wider use among intellectual historians. As I explain in the article, theology largely defined the character and role of the other disciplines in the early modern university (and in early modern intellectual culture in general). But the character and role of theology itself wasn’t unanimously agreed on, either between or within confessions; its disciplinary boundaries were a subject for debate and active demarcation—which is to say, for boundary-work, for deciding what is and what isn’t “theological.”

When I started thinking about boundaries as flexible and in need of demarcation, it gave me a useful lens on a longstanding interest of mine and major theme in early modern intellectual history: the relationship between theology and philosophy. (I should mention, though, that the concept of boundary-work is also relevant for the other boundaries of theology, for example with medicine or law.) It’s very tempting to treat these two somehow as Platonic ideals, as if there were a hard conceptual line dividing them—similarly to how scholars long viewed (and in some cases still view) the division between religion and science. Even studies that look at the influence of philosophy on theology or vice-versa can end up reifying the difference between the two. If we instead see that disciplinary boundary in any particular historical context as having to be constructed, it helps to decompartmentalize our own perspective and puts the dynamic entanglement of early modern intellectual activity into relief.

In addition to taking unorthodoxy and boundary-work individually, I think we can see a correlation between them. Briefly put, theological boundary-work shapes the possibilities for unorthodoxy, and unorthodoxy requires a certain demarcation of the disciplinary boundaries around theology. We see this very clearly in Lubin’s case. Defending his philosophical writings as “unorthodox” requires him to re-demarcate the boundary between theology and philosophy. This correlation puts a seemingly very abstract conceptual problem—the character of theology—in conversation with the concrete, practical realities of reading, writing, and thinking in the early modern period. In doing so, as I suggest at the very end of the article, it puts a different light on the relationship between key cultural and intellectual dynamics of the post-Reformation period.

JS: As you began to think about this article and, consequently, in writing it, what was the importance of situating it within an historiography of the Germanophone world? To put it more precisely, are there elements from Germanophone scholarship that find themselves left out in American scholarship, thereby, requiring renewed attention? Where and how did you put these two types of scholarship into conversation with one another?

TV: Along with putting forward my own heuristic of “unorthodoxy” and arguing that “boundary-work” should be applied more broadly to early modern intellectual history, my article tries to bridge what I see as a divide between Anglophone and Germanophone scholarship on the subject of confessionalization, especially within Lutheranism. The theory goes back in some form to Ernst Walter Zeeden, but it was further developed and made popular by Heinz Schilling and Wolfgang Reinhard in the 1970s, and it started having a significant influence on Anglophone scholarship by the end of the 1980s. By the 1990s and early 2000s, though, several important works critiquing the confessionalization thesis vis-à-vis early modern Lutheranism had been written by Inge Mager, Thomas Kaufmann, and Kenneth G. Appold—all in German. (There’s been, I think, more widespread criticism of confessionalization vis-à-vis Catholicism because of the longstanding terminological/conceptual debate over “Counter-Reformation” and other characterizations of early modern Catholicism.) Since then, Kaufmann has been the most prominent critic of the thesis, putting forward “confessional culture” (Konfessionskultur) as a better conceptual category and one that allows for more flexibility and diversity. There remains a lively debate about how best to characterize Lutheranism in this period, and a younger generation of German scholars in turn has begun creatively building on the work of Kaufmann and others. While my article aims to make a new contribution to this debate, I hope that it can also communicate an updated sense of the status quaestionis to Anglophone scholars—non-specialists in particular—who often describe a version of Lutheran confessionalization that doesn’t account for more recent German scholarship.

JS: I want to place specific emphasis on your point in section II where you describe in exciting detail the status of the theologian in this context. You say that Lubin, by appealing to his established professorship at Rostock and the wider Lutheran community, was able to provide an effective rejoinder against Grawer with relative ease. Is this success particular to one spatial context, namely, a post-Reformation Lutheran Germany? Or, could it occur in other contexts outside of Germany, or even temporally closer to the Reformation?

TV: I argue that Lubin’s success depended not only on his institutional position (though that was an important factor) but also on the malleable character both of orthodoxy, allowing for what I call “unorthodoxy,” and of the disciplinary boundaries around theology, allowing for boundary-work. These two correlated factors are clear, I think, for Lutheranism in the Holy Roman Empire c. 1600. As I explain in the article, German Lutheranism’s territorial character made it highly diverse and divided, and the boundary between theology and philosophy was hotly disputed, creating plenty of room for “academic unorthodoxy.” I wanted to make this case specifically for Lutheran intellectual culture, because I think its vibrance has been underappreciated, thanks to the narrative of confessionalization as well as a longstanding bias against “Lutheran Orthodoxy” (the period’s longstanding moniker) as too intellectually “conservative.”

But, I also think that “unorthodoxy”—and specifically the academic variety I deal with in my paper—can be applied to other early modern intellectual cultures as well. After all, as I note at the very end of the article, the Reformation raised the stakes both for “orthodoxy” and for the character and boundaries of theology as an authoritative discipline that determined orthodoxy—i.e., for both ingredients of “academic unorthodoxy,” as I characterize it. Even in Catholicism—which had an important degree of transnational institutional unity, in contrast to Lutheranism and Reformed Protestantism—there were plenty of jurisdictional divisions, which could lead to the same sorts of tensions that I argue both allowed for and spurred creative intellectual work at the boundary of theology and philosophy. I would like eventually to look at academic unorthodoxy in a more cross-confessional, explicitly comparative way, but I also hope that scholars working on other contexts can take up the conceptual tool and find it useful (as well as further refine it!).

Moving temporally closer to the Reformation, my argument would have to be somewhat recast. By 1600, confessional lines have been pretty well drawn. That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a great deal of intellectual flexibility: that’s my whole point. But, it does mean that being “orthodox” and having an “orthodox” conception of theology meant something different at that time, or was inflected differently, than if we turn back the dial to, say, 1550, when things are much less clearly defined, especially within Protestantism. So, “academic unorthodoxy” would have to look a little different as well. But I think there’s at least more appreciation for the variety of options on the table c. 1550 than c. 1600, which is why I wanted to focus on the later period, when the confessions have taken clearer institutional shape. In both periods, though, I think what those intellectual options actually were still needs a good deal of mapping, which I hope my work can contribute to.

JS: In your final section, you identify a significant historiographic problem, namely, that frameworks which try to force binaries in the intellectual culture of religious institutions lack an appreciative nuance for “flux” and its relationship to the formation of ideas. This flux, in turn, also seems to suggest an important insight on the relationship between “context” and “text,” between history and norms. As a way of understanding concretely this relationship that operates at the core of intellectual history, what would be some mis-readings versus correct readings of Lubin and his wider religious culture? How does the language and implications of “belief” (i.e., faith-commitment) factor into historical interpretation?

TV: I point out three potential misreadings at the end of my paper. First, it would be easy to interpret Lubin’s construction of philosophy as a “safe” category for his writings, outside the sphere of theological judgment, as part of an early modern emancipation of philosophy from the control of theology. This interpretation, though, misses both the theological judgments that go into Lubin’s construction of philosophy as well as the fact that this is a construction—that is, an example of boundary-work in action. This is where the idea of “flux,” specifically disciplinary flux, is most relevant. Early modernity was a period of tremendous, structural transformations in European intellectual life, and it therefore doesn’t help us to treat any discipline, let alone such central ones as philosophy and theology, as transhistorical constants.

Second, I want to distinguish the methodology I’m suggesting from others that may seem similar. Some scholars have argued that giving “orthodox” doctrine a special status distorts our historical analysis by adopting the discourse of the dominant religious authorities at the time. “Unorthodoxy” might seem similar, and I’m in fact trying to counter a similar problem; but I think that not acknowledging the religious ideals and doctrinal standards of a particular culture hinders rather than promotes our understanding of that culture. I don’t think you can understand Lubin’s writings without thinking about how he and his contemporaries coded particular positions as acceptable or unacceptable, and how different contemporary circles coded things differently.

Third (and this gets closest to your question about belief), I don’t want readers to take away that Lubin was simply dissimulating his strange ideas in order to “seem” an orthodox Lutheran. Now, during his self-defense, he did misrepresent his views on the relationship between philosophy and theology, and he used some linguistic slide-of-hand to shrug off Grawer’s attacks. To claim that his statements make him secretly heterodox, though—that’s a retrospective, normative judgment by the historian, as I said above, and in this case (as in most) not one I think is merited. It’s much more revealing, in my view, to accept Lubin’s and his community’s opinion of his orthodoxy, and thereby to challenge and pluralize our understanding of what intellectual options were on the table in early modern Lutheranism.

Jacob Saliba is a PhD student at Boston College where he specializes in modern European intellectual history. His primary focus is twentieth century France, studying the political, philosophical, and religious movements that become profoundly intertwined during the interwar years. Some major themes include: existentialism, phenomenology, personalism, and New Theology. He also holds an MA in political philosophy at Boston College.

Edited by Tom Furse

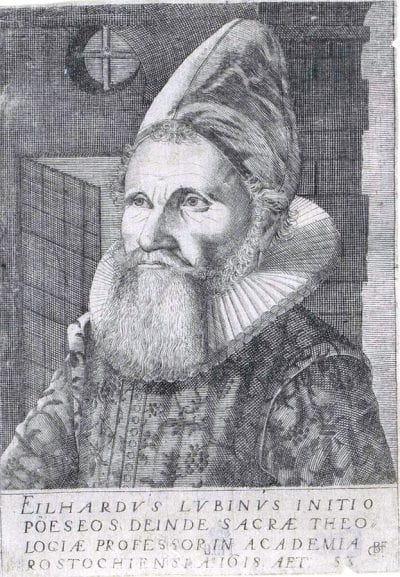

Featured Image: Eilhard Lubin, Creative Commons