By Osama Siddiqui

Upal Chakrabarti is an Assistant Professor in the Sociology Department at Presidency University in Kolkata. His research interests focus on intellectual history, colonialism, political economy, agrarian studies, science studies, and governance. He received his PhD in History from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and has been a Fellow at the Institute for Critical Social Inquiry at the New School for Social Research. His research has been published in journals like Modern Asian Studies, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, and South Asian History and Culture. He is currently working with the British Library and the University of Chicago in preparing an archive of the institutional records of the Hindu/Presidency College, the first institution of western education in Asia, and editing a collection of essays on institutional micro-histories, science, disciplinarity, and pedagogy in colonial south Asia.

Osama Siddiqui spoke to him about his recent book, Assembling the Local: Political Economy and Agrarian Governance in British India, published in 2021 with the University of Pennsylvania Press as part of the Intellectual History of the Modern Age series.

Osama Siddiqui: Congratulations on this important and pathbreaking book. I’ve really enjoyed reading it! Your book offers a new optic with which to read the relationship between political economy, empire, and liberal governance, which is the category of the local. I would like to start our conversation by asking you about how you came to this project and why you decided to focus on the category of the local in writing an intellectual history of political economy.

Upal Chakrabarti: I came to this project from my student days. I had an abiding interest in agrarian history, and once I started reading agrarian histories of South Asia, I realized that there was a time when all historians were, in some ways, agrarian historians! This was also the moment when economic history dominated the historiography of South Asia, and much of the material of economic history would typically focus on the agrarian administration of South Asia. As I read these works, I realized that almost the entire body of this very powerful field of history writing hinged on a kind of empirical depth to such an extent that, in reading these works, one would simply get lost in the details of ‘facts’. A paradigmatic instance of this tendency is a work like Richard Smith’s Rule by Records, which focused entirely on village records over, say, a century in a particular area of Punjab. It’s a work that was representative of the kind of claim that agrarian histories would make on history writing, on thinking about colonialism, and so on.

At the same time, when I started reading the intellectual history classics of the field – Ranajit Guha’s A Rule of Property for Bengal and Eric Stokes’s English Utilitarians and India – I felt that there was something strange in the conflict between the ability to produce a general conceptual account of colonialism’s functioning by intellectual history and the disruption of the generality of such accounts by the empirical thickness of agrarian history. It seemed to me that this disruption hinged entirely on agrarian history’s claim to knowledge of local facts. This made me realize that there is a kind of never-ending relay of empirical details that would not allow one to think of colonialism as a machine or an apparatus that has certain totalizing principles. I realized that this was a political function that agrarian histories seemed to generate with their use of empiricism as a methodological strategy.

So, I started to think whether the particularity with which these histories work can be thought of as having a structure in itself. That is where I started thinking about the local as a category. I started to revisit the immensely important empirical accounts of agrarian regions and started discerning patterns within the variety that they seemed to uphold. This was particularly challenging because of the huge variety of terms that one encounters in reading agrarian history as one moves from region to region. I saw that this variety that agrarian historians were generating was, in a certain sense, what the colonial administration had also faced, and obsessively wrote about. And yet, despite this plethora of particularities, the administrative machinery of colonialism still seemed to work, organize, and strategize its own imperatives. This made me ask whether there was within the logic of colonial rule itself an optic through which this diversity could be reassembled into repetitive principles. This reassembling is what I would call the local. I should mention that the term ‘local’ was omnipresent in my materials. It’s an immanent category that came out of the time, the material, and the logic of governance I was studying. It’s not a category that I imposed on the archive. In my research, I would constantly see this word being deployed to reassemble the diversity of agrarian regions. So, I started to think of the local as a principle for making sense of localities, common to both the archives and the historiography.

Then I tried to trace this principle to political economy. Because of my own Foucauldian approach to colonial government (for more on this, see part 2 of this interview), I already had political economy in mind as a body of thought working crucially to shape governance. But the existing historiography had told us that political economy dealt with universals. My interest in thinking about localities, particularities, diversities, and differences did not sit well with the notion that political economy was ultimately a body of knowledge aimed at the production of universals and that colonialism used political economy to impose its universals on native society. This is where I then tried to search whether within political economy there was a way to make sense of particularity. That’s how I landed at the debate on universalism within political economy.

This was a chance finding in the sense that I was trying to look at all possible connections between political economy and imperial governance. At that time, I did not know about Richard Jones. I did not know that within the very heart of the pedagogic mission of colonial governance, at institutions like Haileybury College, there was a political economist who would talk about political economy in terms of differences and particularities. In fact, in the early days of my PhD, I was in a seminar with Robert Travers and while discussing the teaching of political economy at Haileybury College he suggested to me that I take a look at Richard Jones’s writing. I remember him saying that after Malthus there was a political economist at Haileybury called Richard Jones who has not been much explored. As I started reading Jones, I realized that Jones was not alone, but was in fact part of a wider debate on inductivism and political economy. This gave me an empirical lead to political economy as a possible genealogy for the local.

OS: You write that one of your aims in the book is to “de-romanticize the local” (25). Can you say a bit about what you mean by this?

UC: The romanticization of the local that I’ve tried to challenge in the book can be traced at various levels. One can look, for instance, at how imperial histories have often thought of the peripheries of empire as somehow being sites of resistance, disruption, or limits. There seemed to be a geographical essentialism inherent in such thinking that peripheral locations are seen as capable of disrupting, questioning, or disturbing the power of colonial governance and its categories just by virtue of their location and the distance they embody from the metropolitan center.

I have tried to argue in the book that if we can trace the genealogy of such particularities and differences that are seen as existing in the geographical periphery to the ideational center of imperial thought, then it also enables us to understand how the subjects of empire would work within the logic of these categories. Thus, instead of seeing these subjects as the resisting fringe to the force of such categories, we can think of them as involved in projects of self-transformation that are set in motion by the force of difference lying at the heart of metropolitan thought.

This kind of romanticization is not only present in thinking about resistance, but also in thinking about distinctions between theory and practice, or in talking about the power of ‘on ground’ experiences as opposed to distant gazes of metropolitan thought. Such narratives always seem to contain a disguised, phenomenological claim for ‘experience’ as a category for determining the subjectification of peripheral locations and actors. All of this works at various levels to uphold the local as a kind of liberated space, which I think often prevents us from understanding important motions in politics.

To take just one example (one that is quite detached from the empirical context of my book), consider the participation of different kinds of marginal groups in India today, such as Dalits or tribal communities or Other Backward Classes, in the project of Hindutva. Hindutva has been understood and theorized in a great body of influential scholarship as a movement by and for upper castes and constituted by certain elite ideologies. At the same time, marginal groups have been construed by this same scholarship as being necessarily capable of disrupting Hindutva and blocking the imposition of elite ideologies across the Indian population just by virtue of their very different experiential selfhood. Such claims are always rooted in a certain understanding of the local as the margin of all centralizing metropolitan elite political impulses. But such an understanding has clearly been exposed in terms of its fallacies if you look at contemporary Indian politics today. This is all very removed from the context of my book, but what I’m trying to suggest is that the romanticization of the local works across various contexts and in various lines of scholarship, in which the local stays as a kind of black box, which is what I was uncomfortable with. This was also not to argue that the ‘local’ was an open-ended difference-producing motion. The closures, or structural limits to such differences, have been marked in the book. What I thought was important to establish in the history of political economy and agrarian relations, was the working of universals through differences, and the impact of such processes on the production of specific agrarian subjects.

OS: One of the sites in which the debates you track in the book play out is the locality of Cuttack in Bengal. Can you say a little bit about your choice of this site?

UC: I didn’t arrive at a full conceptualization of the role of Cuttack until much later in the project when I was able to see the entire material and the connections between its various parts. But, initially, I came to Cuttack simply because I was interested in the Bengal Presidency and its agrarian administration. Of course, when we talk about the agrarian administration of Bengal, we are inevitably talking about the Permanent Settlement (1793), which according to all histories of Bengal was a very important policy of early colonialism and shaped property relations, agrarian governance, and the economy of the entire region.

Cuttack struck me as a very interesting site because it came to be occupied by the East India Company ten years after the implementation of the Permanent Settlement (i.e. in 1803) and the Company never extended the Permanent Settlement to this region. Company officials kept saying that the Permanent Settlement was not suitable for this particular locality. Once I saw this case, I understood that here was a conversation about the appropriateness of a particular policy with respect to local specificities.

The Permanent Settlement itself had, of course, been devised after a long debate. What was interesting to me was that the conversation about the local specificity of Cuttack was happening right after this long debate. So, in essence, there was a situation where a policy that had been arrived at after a long and elaborate debate was quickly abandoned and a new debate on the inapplicability of the policy started. Cuttack was one of these sites where this debate took place early on.

More interestingly, once I started reading around this, I realized that there were many other regions in other parts of India where the same debate was taking place with respect to other policies. For example, the government thought that the Permanent Settlement was not suitable for other localities, so they devised a different policy, such as the ryotwari settlement. But very soon the ryotwari too was thought to be inapplicable to other localities and there was a shift to the mahalwari policy. Very soon the mahalwari policy too was deemed inapplicable. There seemed to be, therefore, a logic of endless displacement and deferral of all big policies, which was happening from within the space of colonial governance. In other words, there seemed to be a limit of all policy realized almost as soon as the policy had been formed.

I understood then that what was happening in Cuttack might initially have struck me as an anomaly, but that was not the case. Cuttack was thought to be unique in some way or have some peculiar features, which is supposedly why the Permanent Settlement could not be extended there. But when I saw that this logic of inapplicability was in fact general, I realized that the anomaly was itself a model. How was it that an inapplicable zone was becoming a generalized condition? This made me then think about the inside-outside relation and the nature of the outside of a model as the inapplicable zone for a policy. I concluded that there was a structural condition in the way governance was being set up, which was generating this conversation that every policy will produce its limit almost right at the time it is formulated. Elsewhere in the book I explain this principle of governmental self-limitation as the logic of the local.

OS: A major argument that sets up the book is that political economy in Britain itself underwent an epistemological reorientation in the early-nineteenth century. What was this reorientation about?

UC: The reorientation of political economy I have explored in this book occurred at the precise moment of political economy’s rise to dominance as a doxa and as the defining intellectual backbone of industrial modernity that Britain was stepping into. Right at that very moment, there was within political economy a range of debates over the dominant formulations of its categories. At the time, the dominant formulations of its categories were Ricardian. The major figures in this movement included not only Ricardo, but also particularly Mill and McCulloch, the two zealous devotees of Ricardo. They had foregrounded Ricardo’s formulations as the defining formulations for political economy. This is, more or less, how political economy’s history in nineteenth century Britain is narrated by most of the influential accounts of intellectual history.

However, what I found was that Ricardian political economy was actually under attack from different directions right at its moment of blossom. These attacks came from various perspectives and claimed that the universalism of Ricardian formulations could not sustain critical scrutiny. A number of political economists picked up on different categories of Ricardian political economy, such as wage, rent, profit, and even distribution as a field or production as a field, and so on. All these categories were very seriously interrogated by these attacks on Ricardian political economy.

Among these critiques, the one I thought was quite influential and had not yet been taken note of in the standard canons of the history of political economy was the empirical-inductivist critique of Ricardo. On the face of it, it would seem that an empirical challenge to Ricardian categories would not allow political economy to even get formed as a coherent body of thought because all these categories, once they were interrogated by an empirical standard, would presumably dissolve. But this was not what happened because inductivism in the way that William Whewell (along with other influential thinkers like Charles Babbage, John Herschel, and the entire group of New Baconians in Cambridge) framed it, was supposed to be productive of greater universalism, greater than even what Ricardian categories claimed. In other words, this inductivist challenge had the effect of pushing political economy in the direction of claiming even greater universalism.

This was an important epistemological change and it opened up political economy to a world of differences. Literally, a globe of difference was opened up for political economy to navigate: differences in social fabric, political systems, property forms, economic practices, and so on. According to this epistemological rethinking, political economy had the capacity to navigate, assemble, and totalize these differences, but to do so it had to release itself from a fundamental naturalism, which Ricardian ideas were rooted in, like the fertility differential for rent, for example. In a way, we could say that political economy was becoming sociologized. It was getting linked to questions of history and political philosophy, which was supposed to give it greater valence in terms of its universal capacities.

Later in the nineteenth century, all of this was taken ahead by John Stuart Mill. Mill redefined Ricardianism and did so by drawing on this inductivist attack on political economy that was launched earlier in the century. Mill’s debt to this inductivist attack is not specified in the canonical works of the history of political economy because these works tend to read these intellectual relationships in unreconstructed empirical terms where they try to understand, for instance, whether Mill read X or referred to X in making a statement, and so on. But that is not my approach to the intellectual history of political economy. I read Mill’s redefinition of political economic categories in terms of the way the entire discourse is changing shape and how that change can be traced to earlier conversations within that discourse. More generally, I examine political economy in terms of its epistemological functionings, moving away from both Skinnerian contextualist approaches, as well as more simplistic empirical ones.

Osama Siddiqui is an assistant professor in the Department of History and Classics at Providence College. His current book project focuses on the translation and reception of British economic ideas in colonial India, specifically how thinkers like James Mill, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall and others were translated into Urdu in the nineteenth century. His research has been supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Historical Association, the Social Science Research Council, and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada. He completed his PhD in History from Cornell University.

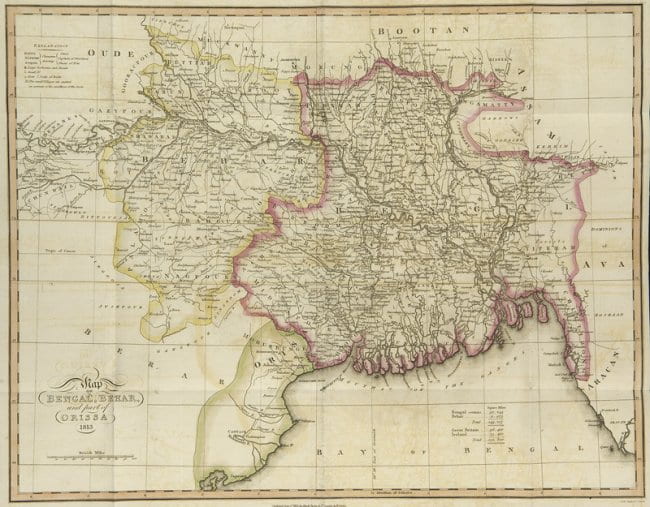

Featured Image: Charles Stewart, Map of Bengal, Behar, Orissa, 1813, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.