By Hans Wallage

Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine sparked the largest refugee crisis within Europe since World War II [1]. Due to bombardments, atrocities, and food shortages, refugees are waiting in line to cross the borders of Hungary, Moldova, Poland, and Romania. Stories about the reception and shelter of these refugees have been mostly positive in international media. According to online news outlets like CNN and the BBC, neighboring countries have welcomed Ukrainian refugees and expressed feelings of empathy and solidarity with their fate.

However, the reporting also revealed another side of the same coin: some people who tried to cross the border were denied access. It appears that refugees with African or Asian heritage have been sent back to the Ukrainian war zone. Due to their ethnic background, border guards often regarded members of these groups as non-deserving refugees, coming from third-world countries and residing illegally in Europe.

To differentiate between groups of refugees is not a new phenomenon; it dates at least to the early modern period. During several early modern refugee crises, communities facing limited resources to provide shelter discussed which refugees deserved help and which did not. These communities grappled with the question of whether all refugees were to be treated the same, and if not how to make distinctions amongst them.

In this piece, I consider the impact of refugee flows from one conflict, the Khmelnytsky Uprising, on the idea of the refugee. I situate debates on this topic within the Jewish community of seventeenth-century Amsterdam where many of the refugees arrived. My piece analyzes how and why the idea of distinguishing between deserving and non-deserving refugees emerged in that community, and the consequences that this political debate had for the refugees themselves.

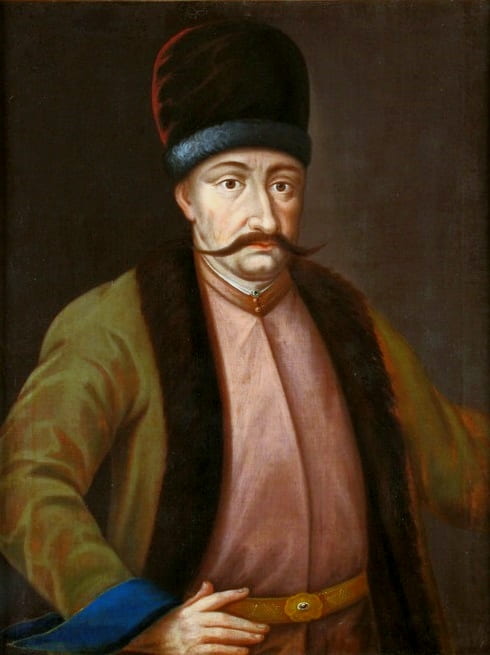

In Rescue the Surviving Souls, Adam Teller analyzes the grim origins of the crisis which would spur Amsterdam’s Jewish community to rethink their ideas of the refugee. The Khmelnytsky Uprising broke out in 1648, as a revolt against the dominating Polish nobility (szlachta). It began with Cossack forces in thePolish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s eastern territories under the leadership of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a minor aristocrat and military leader who had served with Cossack forces since 1617. These units had been established to protect the Commonwealth’s southeastern border from enemy incursions, but rebelled against Polish rule after years of failure to pay their salaries and broken promises to improve the Cossacks’ social status.

At first glance, this rebellion need not have greatly concerned the region’s Jews. But circumstances changed as the conflict grew to include more parties. Many of the peasantry joined the Cossacks, which introduced new sources of tension and forms of hostility, including rising antisemitism, into the conflict. The peasants’ grievances were now specifically directed against Jews. Since the sixteenth century, Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been given the task of collecting and delivering tax revenues for landlords. Because of their intermediary position, and longstanding ethnic and religious animosities, Jews were viewed by many peasants as complicit in their oppression.

In other words, the Jewish population had become the visible embodiment of the hated serf system. As a result, when the Cossack armies and the peasantry marched through the Commonwealth, including territories in modern-day Ukraine, peasant rebels went from town to town, destroying villages and burning down synagogues. Thousands of Jews were murdered in the most gruesome ways, with many drowned or burned on the pyre, those who were healthy and had reached maturity would be sold into slavery.

Once it became clear that the city walls were no guarantee of safety, Jews fled westward in large numbers, hoping to stay ahead of the advancing armies. The persecutions created chaos in which hundreds of thousands of panic-stricken Jews found themselves on the road, desperate to maintain their personal safety, and looking to start a new life in cities further West such as Kraków, Prague, Vienna, Hamburg, Venice, or Amsterdam.

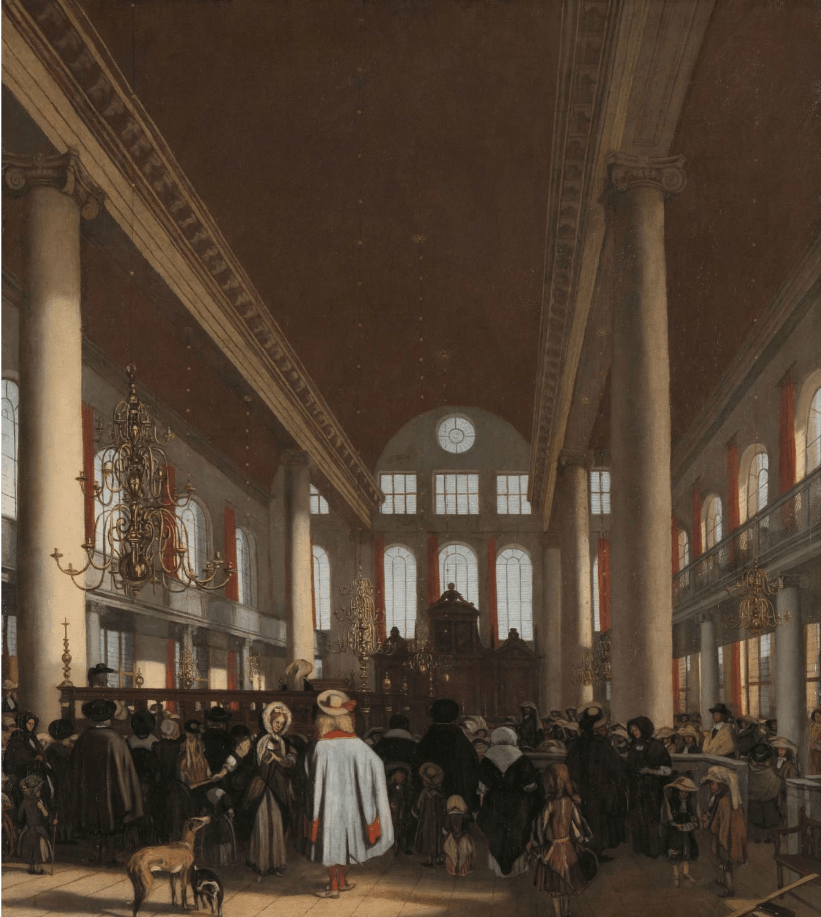

In Amsterdam, the Sephardic board, mahamad [2], was hesitant to shelter Ashkenazi Jews when they began to arrive around 1648 [3]. The Jews from Poland and Lithuania had little in common with the Spanish and Portuguese Jewry already long settled in the Netherlands. This was partly because of different ideas about proper religious life: They spoke different languages, had their own religious rituals, and practiced their own customs. But it was also a matter of social distinctions. In fact, what most disquieted the Sephardic community leaders was the poor circumstances in which the Ashkenazim arrived.

The Sephardim had good trade contacts in the Atlantic-oriented economies of their former home countries. This network had found them a respectable place within Dutch society, and allowed them to continue their work in the new environment after being forced out of the Iberian kingdoms. As a result, they were better able to earn a living in the Low Countries. The newly arrived Jews from the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth had no such advantages, especially given the chaotic circumstances under which they had fled. As a result, the Ashkenazim in Amsterdam were much poorer, depending on help from the established, mainly Sephardic, community.

Despite the differences, and some mutual mistrust, the Sephardic board initially interpreted new arrivals above all as co-religionists. As such, the Amsterdam community had certain obligations toward them. The board members stated that it was a “religious commandment to help and assist persecuted Jews” – in Judaism called a mitzvah. The established idea of performing a mitzvah gave structure to the way that Amsterdam’s Jewish community responded to and offered help to the victims of the Khmelnytsky Uprising. The board soon wrote a letter to their members finalizing their decision. It announced that the imposta, a communal tax to pay for religious charity, had to beraised to shelter all incoming refugees, regardless of cultural difference or economic prospects.

As a result, the mahamadissued resolutions decreeing that it was not permitted to give money to Ashkenazi Jews who were begging “in front of doors and the esnoge” [4]. Despite this initiative, the board kept receiving complaints from the city council about the public visibility of Jewish homelessness. The complaints led the mahamad to fear that if they remained identified with the newly arrived Jews, whose publicly visible poverty so displeased the authorities, this would lead to sanctions against the entire Amsterdam Jewish community.

Therefore, the mahamad decided to search for a long-term solution to the growing homelessness problem. This economic and political pressure led them to reconsider their earlier idea that it was a “religious commandment to help and assist persecuted Jews”. Instead, they began to draw distinctions amongst the refugees, deciding who was deserving and who was not, which in turn served as a strategy to display their own distance from the refugees to the city authorities.

According to the mahamad, the begging problem revealed that there was a difference between what they called: “sincere refugees” and “economic profiteers”. They defined sincere refugees as those who searched for work upon their arrival in Amsterdam. So-called economic profiteers may well have had legitimate reasons to flee, but they were then seen to have taken advantage of the generosity of society, and their fellow Jews in particular, by begging. In this way, the emphasis shifted from an assessment of refugees’ origins to an assessment of their behavior.

For example, a member of the mahamad wrote in 1658: “they [the profiteers] were unable to help in the peaceful lands where the goodness of the blessed God exists.” According to the same letter, it was easy to prove who was a sincere refugee and who was not. Amsterdam, they argued, offered sufficient economic opportunities for any new arrival to be self-sustaining so any refugee not working should automatically be regarded with suspicion.

In the eyes of the mahamad, the fact that some of the refugees were begging revealed that these were “lazy people” who tried to profit from the goodness of the congregation. This new idea, that a deserving refugee was one who behaved according the local view of appropriate economic behavior, allowed the mahamad to implement policies which treated some arrivals differently from others. Eventually, they concluded that all Polish, German, and Lithuanian beggars were to be classified as “profiteers” who had to “go back to their country,” regardless of their safety.

The new distinction between a deserving and a non-deserving refugee had considerable practical consequences. On 12th of July 1656, the mahamad paid 550 guilders to a ship captain named Jan Goosens for the service of transporting 125 to 130 people, explicitly stated to be poor Polish-Jewish refugees, southeast via the Rhine to Frankfurt. This incident was far from an isolated one. As part of the long-term solution sought by the board, the Sephardic community decided to send those who did not fulfill the requirements of a ‘sincere refugee’ back East. Still afraid to return to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, many settled instead in the growing Jewish communities of central European cities like Frankfurt or Cologne.

Considering the case of the refugees from the Khmelnytsky Uprising shows that the kind of distinctions made amongst refugees today are not new. In the seventeenth century, the Jewish community in Amsterdam already distinguished between “sincere refugees” and “economic profiteers.” Although there are powerful echoes here of our modern ideas, the categorization of the deserving and the undeserving relies on different intellectual framings and depends different economic and political circumstances in each historical case.

In the seventeenth century as today, however, authorities formulated their understandings of new refugees at a similar intersection of political, economic, religious, and intellectual concerns. As similar ideas take shape during the present refugee crisis in Ukraine, this historical case can help us to think about the way that these distinctions develop and the consequences that they may have for vulnerable people seeking safety.

[1] UNHCR estimates that 3.5 million have fled Ukraine so far. The total number of refugees from the Syrian Civil War remains the largest in recent times, with 6.8 million people displaced to date.

[2] Sephardi Jews, also known as Sephardic Jews or Sephardim, and often referred to by modern scholars as Hispanic Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population who coalesced in traditionally established communities in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal).

[3] Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim, are a Jewish diaspora population who coalesced in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. In the late Middle Ages, due to widespread persecution, the majority of the Ashkenazi population steadily shifted eastward, moving out of the Holy Roman Empire into the areas that later became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

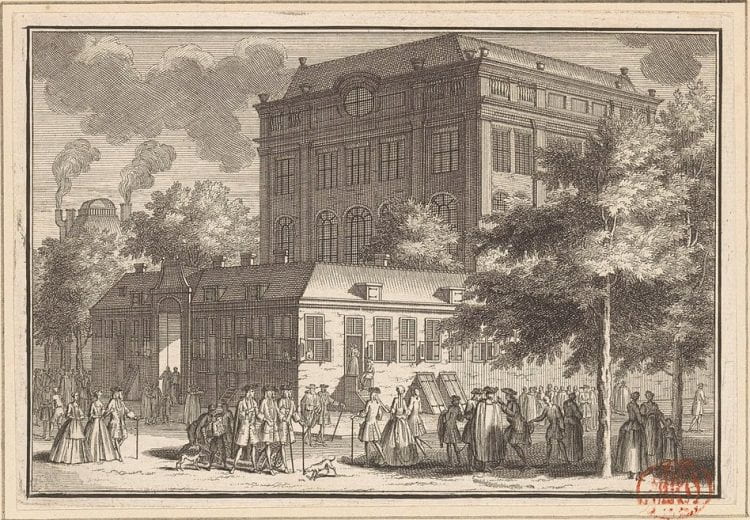

[4] The esnoge was a local Jewish name for the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam.

Hans Wallage is a historian specializing in Jewish and Migration history. He holds BA and MA degrees in history from Leiden University. His bachelor thesis discussed the returning influence of fascism in Dutch society after the Second World War and his master’s thesis investigated the Dutch restitution process for Holocaust survivors between 1945 and 1960. He is currently a PhD Candidate in the NWO VICI-project The Invention of the Refugee in Early Modern Europe at the University of Amsterdam.

Edited by Alexander Collin

Featured Image: View of the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam c.1675, Wikimedia Commons