By Sanjana Chowdhury

Sarah Ruffing Robbins is the Lorraine Sherley Professor of Literature at TCU. She has published ten academic books, including the Choice-award-winning monograph Managing Literacy, Mothering America (2004); The Cambridge Introduction to Harriet Beecher Stowe (2007); a co-edited award-winning critical edition of Nellie Arnott’s Writings on Angola (2011); and a monograph building links between archival research and public-oriented humanities projects, Learning Legacies: Archive to Action through Women’s Cross-Cultural Teaching (2017). She is presently co-editing a special issue of English Journal on the impact of current curriculum wars on secondary education in the US; serving as the coordinator of selection and assessment for Building a More Perfect Union, a major NEH grant supporting over three dozen participatory humanities projects; and doing preliminary research for a monograph on the role of the arts in the construction of counter-histories addressing justice issues. With Andrew Taylor and Chris Hanlon, she co-edits the book series on “Interventions in Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture” for Edinburgh University Press.

Sanjana Chowdhury spoke to Dr. Robbins about the 2022 anthology Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures, 1776 – 1920, which was another collaboration with Dr. Taylor, also including Dr. Linda K. Hughes, Adam Nemmers, and Heidi Hakimi-Hood as additional team members. Dr. Robbins is serving as faculty sponsor for that project’s companion website, which is managed by a team of graduate students and alumni from TCU.

Sanjana Chowdhury: What was the inspiration/motivation/starting point for the Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures anthology?

Sarah Ruffing Robbins: There are several strands there that are worth mentioning. One inspiration came from teaching a Transatlantic Literature course with Dr. Linda Hughes. We got the idea not too long after I came to Texas Christian University (henceforth TCU) in Fall of 2009. Since we both worked in Nineteenth-century Studies, and we were both aware that Nineteenth-century Studies was becoming increasingly global, both in research and teaching, we thought we might be well positioned to envision a Transatlantic course. So we started meeting and planning the class and thinking what it might look like. We were fortunate enough to get an Instructional Development Grant from TCU, which allowed us to bring a series of scholars to the first offering of the course. So we developed the first version of the syllabus, and we got it ready to run, and we had several visiting scholars come to our class at different times during the course. One of them was Dr. Meredith McGill, who has done amazing work on the culture of reprinting. One was Dr. Kate Flint, who has that wonderful book on the Transatlantic Indian, and another was Barbara McCaskill, who works on the Black Atlantic. Having those scholars come in was doubly helpful because they each taught a seminar session with us, and they also reflected with us on the syllabus, on what was there and maybe what was not there the first time and how we could make it better. From those conversations we began to realize that everyone who was trying to do transatlantic pedagogy was hoping to have more infrastructure and guidance for their work, and that is how we got the idea for the first book, a collection of essays called Teaching Transatlanticism. We approached Edinburgh University Press about publishing it because we knew that they had already done work in Transatlantic studies. They were enthusiastic, and published that first collection entitled Teaching Transatlanticism: Resources for Teaching Nineteenth-Century Anglo-American Print Culture (edited by Linda K. Hughes and Sarah R. Robbins, Edinburgh UP, 2015). The Table of Contents and the Introduction of collection are available on the website Teaching Transatlanticism. That book did well, and it led the press then to approach us about maybe doing a primary text anthology. So it was an iterative process, growing out of our teaching and also out of a wonderful connection we made with an interested press that has a sustained interest in the topic. Andrew Taylor, our co-editor, had already done a lot of work with the Edinburgh University Press, and he came on board. So the three of us – Linda, Andrew, and I – started thinking about the anthology. That was kind of the starting point.

SC: That is such an interesting backstory! It is amazing that the Transatlantic Anthology came out of creating a course, because I always imagined it to be the other way around since we tend to follow a book to teach a course.

SRR: That is often the general assumption, but I think it is important for people to know that teaching really came first for us. The learning, however, goes back even further. When I was at the University of Michigan for my doctoral studies, my very first course was a Transatlantic Literature course with Dr. Julie Ellison. So I was certainly trained in and encouraged to envision the possibilities for Transatlantic Studies. Even before that, when I did my Masters at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill many years ago, I took two courses with Dr. Richard Fogle, who was a nineteenth-century specialist. I would not say he organized his courses as transatlantic, but he worked on both sides of the pond, as it were. Edgar A. Poe, Henry James, and Nathaniel Hawthorne were the main figures in one of the courses I took with him, and in that class he did present such authors in transatlantic terms. (I also took a marvelous course with him on British Romantics, wherein he made connections between those poets and American writers. I guess you could say that I have been thinking of and working with Transatlantic literature and pedagogy for multiple decades.

SC: The entire process behind your anthology is very informative. I completely agree that we should be cognizant of how anthologies shape fields of study. Are the organizational categories of the Transatlantic Anthology also a product of the thought process about formative powers of anthologies? When you organized different authors and works under different categories, what was the reasoning behind the decision? How do you think this organization helps the reader?

SRR: When you organize materials for teaching or scholarship, what you are doing is constructing an artificial system. It is not a material object that exists in the world, but rather a deliberate construct. Our collection of ten themes came out of collaboration among the three lead editors – Linda, Andrew, and me, as well as the associate editors and advisory board members.

There is a story that Linda loves to tell, and I want to credit her for it. In a really pivotal moment in the early envisioning of the anthology, we were able to get together in person in Washington, DC, during a very early stage of our work. We were all three presenting together at the American Literature Association (henceforth ALA). It was so generous of Linda to go to ALA because it is not one of her regular conferences, and Andrew flew over from Edinburgh. We spent a whole day in my daughter’s condo in DC while she and her husband were off at work, and we literally sat at the kitchen table all day talking about how we wanted to organize and why we wanted to organize that way, and our initial idea that it should be thematic. We tried to blend chronology and themes for the anthology, but we could not see an easy way to do it quite as smoothly as a straightforward chronological listing as in some anthologies, and we did not really want to. We spent some time thinking really hard about what the most important topics were that people would probably want to teach and we literally argued, in the academic sense, over those different themes. Some of them were obvious, like “Migration and Settlement”. “Abolition of Slavery” initially seemed like an obvious organizational theme, but after some thought, we realized that we needed to think of the aftermath too. This was well before the 1619 Project (initiated by The New York Times in 2019) that marked the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery and that focuses on the contribution of Black Americans to the national narrative of America. I think that, in a sense, we were anticipating the argument of the 1619 Project that slavery as well as anti-slavery does not have a neat start and end date. It has a long life, broad consequences, and cultural legacies. So one thing that we were trying to do by organizing thematically was to resist the very chronology that we were using. Although we wanted to focus on the nineteenth century, and that is the time period we co-editors work in for much of our scholarship, we immediately undermined our chronology by starting with 1776 and ending with 1920. To say “Long Nineteenth Century” is not a new thing, but we had to put some thought into what should be the starting point, and how we were going to trace the thematic threads across this long time period we were working on.

By the end of that day in DC, we had about seven or eight themes, and the advisory board was extremely helpful in separating some of the themes. For example, “Migration” and “Travel” became separate themes, because the kind of travel you do when you are Henry James or Edith Wharton going on a trip is very different from the migration for settler colonialism. We also received important advice from the board about categorization of authors. Barbara MacCaskill, for instance, told us to make a commitment that Black writers would not just be in the expected categories but across all ten themes. So we were attentive that Black writers and Indigenous writers – First Nations and Native American authors – would not be cubby-holed. That is how we began to think of potential primary texts to go under particular themes.

Literature anthologies tend to be chronological, and thematic periodization, such as Romanticism or Realism, seems to be confined to specific time periods, when in fact modes of thinking are not actually constrained to and fenced off in a particular period of time. So, one of the things our anthology is actively trying to resist is the practice of assigning a firm starting and ending point to a literary and/or political movement. One of the ways we carried out our resistance is by organizing the anthology in the ten themes (which are now also mirrored on our companion website). Within each theme, we did organize texts somewhat chronologically, but twisted that a bit too by having clusters of texts that were responding to each other not necessarily presented exactly chronologically. We want readers to have those moments of surprise and to see the places where we have resisted our own structure.

We did the same thing with “Anglophone”. We are not experts in multilingual dimensions of transatlantic study. For instance, I speak and read French and Italian. But I do not work in other languages that were important to the culture of Transatlanticism in the nineteenth century, such as Spanish or Portuguese So we had to recognize the limits of our own expertise, but, at the same time, we wanted to acknowledge that the Anglophone textual exchange was constantly interacting with other languages. There are several instances in the anthology where we are presenting a text in English but it comes out of translation, and we discuss in the headnote for such texts the role of translation and the translator. We are inviting our readers to think about the way “Anglophone”, just like time periods, is not a clearly marked-off territory of knowledge, but rather there are people and discourse moving back and forth across different languages. Even when transatlantic authors are publishing in English, they are interacting with other languages. Overall, I would say that in each of the words in the title of our anthology – “Transatlantic” and “Anglophone” and “Literature”, we are trying to honor but resist each category.

SC: It is very enlightening to hear about how your academic practice of resisting constructs shaped the organizational themes of the anthology. I especially liked how the various writers of color appear across all ten themes, which is frankly unlike any other literary anthology. Usually, we tend to read authors of color when we are discussing race and racism, or women authors when we talk about gender issues. The Transatlantic Anthology, I believe, is setting the tone for literary anthologies by consciously not putting authors into historically predetermined boxes.

SSR: This is where I want to send a shout-out to generous colleagues like a wonderful cohort of Black scholars—such as Koritha Mitchell and Joycelyn Moody—who came to a luncheon I arranged during a conference on women’s literature and spent that hour-plus spinning out recommendations of Black Atlantic writers, especially women, whose texts should appear in the anthology. Our advisory board members were essential; we asked them to make suggestions for individual texts, and that is how we generated such a wealth of varied literary works. I am also going to go back to something you said earlier about scholarship preceding teaching. There were, of course, pivotal pieces of scholarship, such as Jace Weaver’s The Red Atlantic (2014), which served as a kind of scholarly “Bible” for helping us think about who were major First Nations and Native American writers that we should read and incorporate. We were also thinking about the women writers who had worked their way into important positions in the scholarship on nineteenth-century literature and transatlantic culture. We were thinking in terms of intertextuality, so that individual texts within a section would speak to each other, in addition to how the texts from one section would interact with other sections. This is why certain authors appear in multiple thematic spaces.

It was extremely beneficial that we already had the Teaching Transatlanticism website, and we knew that taking out a text did not mean it was not part of the conversation, since we could feature the text on the digital anthology. In fact, we came to recognize that some texts might be better positioned on the website, where they could appear under multiple categories, and need not be excerpted as much as is necessary for the print anthology. We were trying to make thoughtful decisions in that regard, and also invite people to think conceptually to bring more texts to the website in the long term. Anyone who teaches with the Transatlantic Anthology will probably think it should have a particular text or author that does not appear there, and the Teaching Transatlanticism website provides us the space to insert that text or author and facilitate further conversation, helping the field continue to grow organically.

Sanjana Chowdhury is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Texas Christian University. She has also completed a graduate certificate in Comparative Race and Ethnicity Studies. Sanjana is the copy editor of the digital humanities project Teaching Transatlanticism, an online resource for teaching nineteenth-century Anglo-American print culture. Her peer reviewed essay on Hinduism has been published in the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing (ed. Dr. Lesa Scholl), 2022. Her research interests include Long Nineteenth-Century literature, marxist theory, postcolonial theory, critical race theory, and British Empire history. She is currently researching foodways of the British Raj.

Edited by Shuvatri Dasgupta

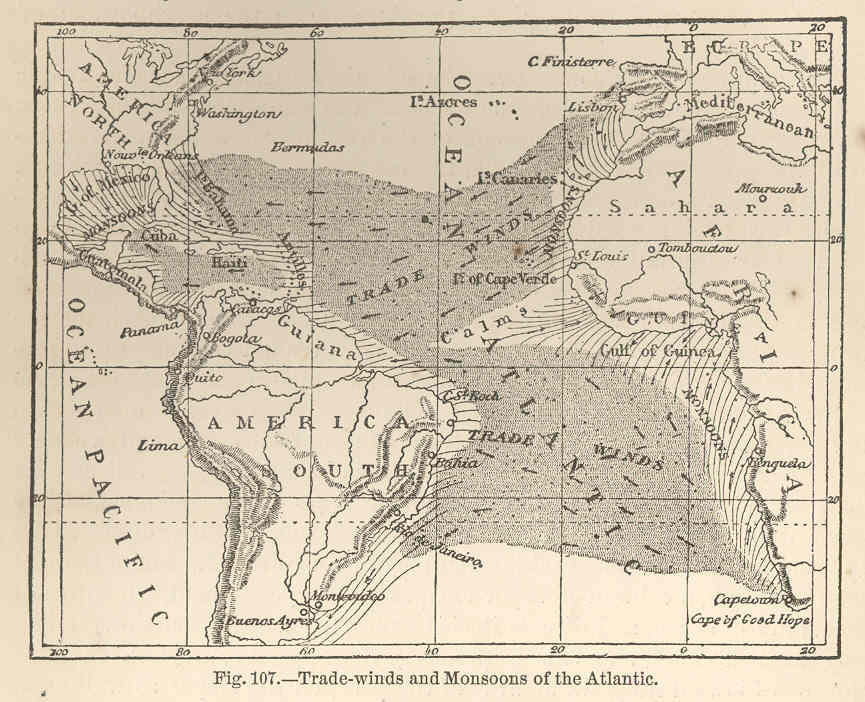

Featured Image: Élisée Reclus (1873) Ocean, Atmosphere, and Life, being the Second Series of a Descriptive History of the Life of the Globe, New York City, NY: Harper & Brothers, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.