By Sanjana Chowdhury

Sarah Ruffing Robbins is the Lorraine Sherley Professor of Literature at TCU. She has published ten academic books, including the Choice-award-winning monograph Managing Literacy, Mothering America (2004); The Cambridge Introduction to Harriet Beecher Stowe (2007); a co-edited award-winning critical edition of Nellie Arnott’s Writings on Angola (2011); and a monograph building links between archival research and public-oriented humanities projects, Learning Legacies: Archive to Action through Women’s Cross-Cultural Teaching (2017). She is presently co-editing a special issue of English Journal on the impact of current curriculum wars on secondary education in the US; serving as the coordinator of selection and assessment for Building a More Perfect Union, a major NEH grant supporting over three dozen participatory humanities projects; and doing preliminary research for a monograph on the role of the arts in the construction of counter-histories addressing justice issues. With Andrew Taylor and Chris Hanlon, she co-edits the book series on “Interventions in Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture” for Edinburgh University Press.

Sanjana Chowdhury spoke to Dr. Robbins about the 2022 anthology Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures, 1776 – 1920, which was another collaboration with Dr. Taylor, also including Dr. Linda K. Hughes, Adam Nemmers, and Heidi Hakimi-Hood as additional team members. Dr. Robbins is serving as faculty sponsor for that project’s companion website, which is managed by a team of graduate students and alumni from TCU.

Read the first part of the interview here.

Sanjana Chowdhury: It is really great that the Teaching Transatlanticism website exists, and, unlike a print edition, digital space is unlimited and perfect for featuring the ever-expanding conversation around Transatlantic literature. It is also on the web, which means it is accessible to anyone anywhere across the globe. Providing the Transatlantic literature resources to readers and scholars everywhere for free is a great political statement too. Since we did talk about categories like race and gender, I would like to hear your thoughts on how education depends so much on social class, race, and gender, and other intersections of identities that are placed on us by society. It appears that the Transatlanticism website is taking a stand that education and knowledge should be free and accessible irrespective of one’s identity categories.

Sarah Ruffing Robbins: Yes, I think this digital space will bring more people into the work of the digital anthology. I am also really excited about how the website is generating some types of texts on its own, like the “Image of the Month” feature. Again, Edinburgh University Press was very generous in letting us have sixty illustrations from the print anthology to publish on the website. It is vital to understand that culture and cultural change did not just happen in words but also in imagery. I think the website has the capacity to make that even more, pardon the pun, visible. As an editorial team, we are beginning to devote more time to seeking out images to include in our presentation of primary texts on the web. One good example is Saffyre Falkenberg’s engaging treatment of a story by Frances Hodgson Burnett, “Little Betty’s Kitten,” which includes a set of illustrations from one of the editions of the story. Saffyre also addresses the role of the illustrator and his place in Transatlantic publishing culture.

SC: As part of the web team, I think the website also provides a particularly inviting space for conversation about issues that remain relevant in the present day, such as questions of gender or race. The fluidity of the digital environment reminds us that culture is ever-changing, even as it reflects the influences of past events, movements, and social issue. For instance, there is the ongoing debate on abortion right now. How do we read and teach texts that contain the history of the Transatlantic Anglophone world as we navigate through and possibly even resist current political changes? As we look for more individual texts to add to the digital anthology, I hope we can also inscribe intertextual connections across texts, themes, and writers; marking those movements with techniques like listing the same entry in more than one theme, or directing users from one text to a related one (such as saying “see also…”), we can help spotlight the various genealogies of ideas and social practices across time and space.

The editor-in-chief of the Teaching Transatlanticism website, Soffia Huggins has recently chimed in on this subject. She stated, “I definitely see the website as an ongoing archive, and with that, I constantly am thinking of what archives ARE and what they DO. Because of the ease and fluidity of the web, I think that keeping in mind how archives craft narrative is perhaps less intuitive than in print but it is just as essential. In building the anthology in particular, I often consider that what we don’t include is as important to that narrative as what we can and do include. As for tracing radical genealogies, I think that is my personal hope for the website. The affordances of the digital anthology to show how texts are connected makes this particularly exciting. The connections between radical and roots come to mind, especially when you think of the ways in which texts are part of larger systems AND the way a website is put together, connected through an intricate series of roots and branches of code.”

SRR: One of the things I love about Transatlanticism as a field is the way it helps us see cultural movements like women’s rights and racial justice across time. Sometimes we feel like our moment is unique, and it might in fact be uniquely terrible – or wonderful – in a certain way, but rarely is it unique and instead have connections to other moments in history. A past period can help us think through strategies for engaging with these important issues.

For example, the anthology was envisioned pre-COVID and the pandemic was not on our mind. The Spanish Flu of 1918 fell out of our cultural memory until we looked for answers in the past during COVID. So, coming back to the question of women’s right to their own bodies and reproductive rights, the anthology does not have a theme specifically labeled “medical”, but we have a few texts scattered across the ten themes. We need to bring attention to certain topics like “medicine” and “disability/ability” in the digital space, and I look forward to doing that. Similarly, one colleague who’s taken a close look at the anthology commented to me recently that she’d like to see us bring together and highlight texts about education–and not just non-fiction ones–in nineteenth-century Transatlantic culture. She was speculating that some of the current curriculum wars – especially in the US, where the political Right is attacking frameworks like Critical Race Theory – might have antecedents in the long nineteenth century.

SC: These are very relevant topics to feature on the website, and also to bring to the classroom. I think the Transatlantic anthology is a great resource for teaching. What do you think are the best ways of adapting the anthology for teaching undergraduate courses, both literature courses and non-literature (for example, Women and Gender Studies, or Race and Ethnicity Studies) courses?

SRR: In a course I was preparing to teach in fall 2022, I found my own work on the digital anthology team led me to consider what texts I’d learned about from that work could be added to my class, especially texts that would be particularly helpful and relevant to my students. We have, for instance, a couple of pieces by Mary Seacole, but I might use more of her book Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole, especially the section on Crimea. One of the things you see right away when you open that book is a map of Ukraine. That is a space that was not geographically familiar to many people three or four years ago, but now it is going to be on everyone’s mind, and people want to be supportive of the experiences of folks who are undergoing the stress of warfare. So, I developed plans to teach from the online anthology – and excerpts from the print one – to touch on some current topics.

SC: That is a very relevant topic and I am sure the students would find it helpful to see historical and literary perspectives about Crimea, Ukraine, and those regions. Since we are on the subject of current events and relevant texts, I would like to touch on the question of race and racial justice. The anthology is very sensitive to and respectful of various issues surrounding race in the long nineteenth century. How do you think the reader should approach the racial topics discussed in the book, especially given the current environment of racial tension in the Western world?

SRR: As you said earlier, we have questions of race woven through the entire anthology. I am especially thinking about texts in anticipation of the Phillis Wheatley anniversary in 2023 – it is the 250th anniversary of her 1773 collection of poetry, the first such collection by an Black American poet, who at the time of her initial publications, was actually a Transatlantic British subject. I want to do some work beyond what is already in the print anthology, that would encourage us to bring more material on to the digital space.

In addition to that, I have been thinking recently about mixed-race identities, and about different strategies of interacting with the questions of race in the light of the anti-CRT movement currently going on in US schools. I want to foreground that a bit more in class, so I picked out two texts from Pauline Johnson. We have one piece by her in the print anthology – a long memoir that appeared in a newspaper that tells her own story of being mixed race and traveling and moving in and out of different cultural spaces. In my class, I wanted students to read more of her short stories, not just the poetry, since I think her critique of how race limits social agency is often more pointed in the prose.

I was excited to have them read some texts that are not in the print anthology or the website yet. And, at the time of this interview, I am starting to work with the members of the class to support their selection and development of new entries, their own new contributions for the digital anthology. Linda and I have used materials from the anthology in the recent graduate seminars, but fall 2022 would the first time for me to teach with the actual physical copy of the book. At the point when we are having this conversation, Sanjana, I’m framing questions to share with those undergraduates. I want to know from my students what they think of the themes and what they think of who’s there and who they might feel is not there, and really encourage them to use the course to think about the way that systems of knowledge get organized. To use John Guillory’s term, the syllabus becomes a culture maker and creates cultural capital. I really want to encourage my students to understand the way those systems get artificially constructed and how they might exercise agency to resist the very structures that are presented to them in any literature class. I hope the way the anthology is organized and the way the introductions to the various sections and annotations are crafted will encourage people to view the anthology as an ever-dynamic process of thinking and learning.

SC: I am sure that would be a very valuable learning experience for your students. It is a wonderful way of being on the inside and outside at the same time, as they see how systems of knowledge are created and what they can do to resist it from within. That is an effective political strategy, and I am very excited to see how this class unfolds.

SRR: I hope you will come visit the class! And I think the “inside-outside” description is a very generative one that I will borrow for the class.

SC: I will certainly come to your class! I have one last question as we wrap up our wonderful discussion today. We have talked about the digital anthology and thinking of it as a dynamic growing organism, but I was wondering if there any future projects you are envisioning in terms of Transatlantic literature of the long nineteenth century or maybe even transoceanic literature.

SRR: We talked a little bit about the Wheatley anniversary in 2023. I am also teaching a diaspora literature course for the first time in spring 2023. There is certainly a lot of nineteenth-century material to look at, but I am also thinking of “transtemporal” literature that will go forward as well as back in time. Of course, when you tear down fences like time periods and other categories, there is always a danger that you get lost in the sheer quantity and possibility of texts, and you also worry that you are going beyond the area where you have knowledge and expertise.

Connecting to your earlier question about teaching Transatlantic literature in a Women and Gender Studies class, I was thinking of how we can teach it when we take “gender and sexuality” as a broader category. It is important to consider how folks who would identify with LGBTQ+ identities are underrepresented in the current version of the anthology, and addressing that limitation is certainly a future project. I think one of the ways that I can imagine using the anthology in a future graduate course is by constructing some alternative anthologies. In the NEH project I mentioned earlier, Making American Literatures, that I did with folks from UC-Berkeley and the University of Michigan, one of my favorite secondary school educators who was part of the learning and teaching team, charged her 11th graders to reorganize their own anthology. I thought that was such a wonderful thing to do. One of her strategies that I have always tried to model on, is never to start at the beginning, but always start with the “now”, with something contemporary to the moment that is important and has roots in the previous periods. I am working on a new monograph, Telling Histories, and I am thinking about what is in the current moment that encourages us to creatively construct engagement with the past. These kinds of texts are not seeking to do factual reporting, but rather a carrying out a creative engagement with the past that admits to being rhetorical and that tries to intervene in the contemporary culture through that imaginative, aesthetic process. I am curious to see how we might use new literature and other artistic productions to rethink some things from nineteenth-century Transatlantic culture more broadly in ways that would be useful to us today and would help us live our lives more thoughtfully and productively.

Sanjana Chowdhury is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Texas Christian University. She has also completed a graduate certificate in Comparative Race and Ethnicity Studies. Sanjana is the copy editor of the digital humanities project Teaching Transatlanticism, an online resource for teaching nineteenth-century Anglo-American print culture. Her peer reviewed essay on Hinduism has been published in the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing (ed. Dr. Lesa Scholl), 2022. Her research interests include Long Nineteenth-Century literature, marxist theory, postcolonial theory, critical race theory, and British Empire history. She is currently researching foodways of the British Raj.

Edited by Shuvatri Dasgupta

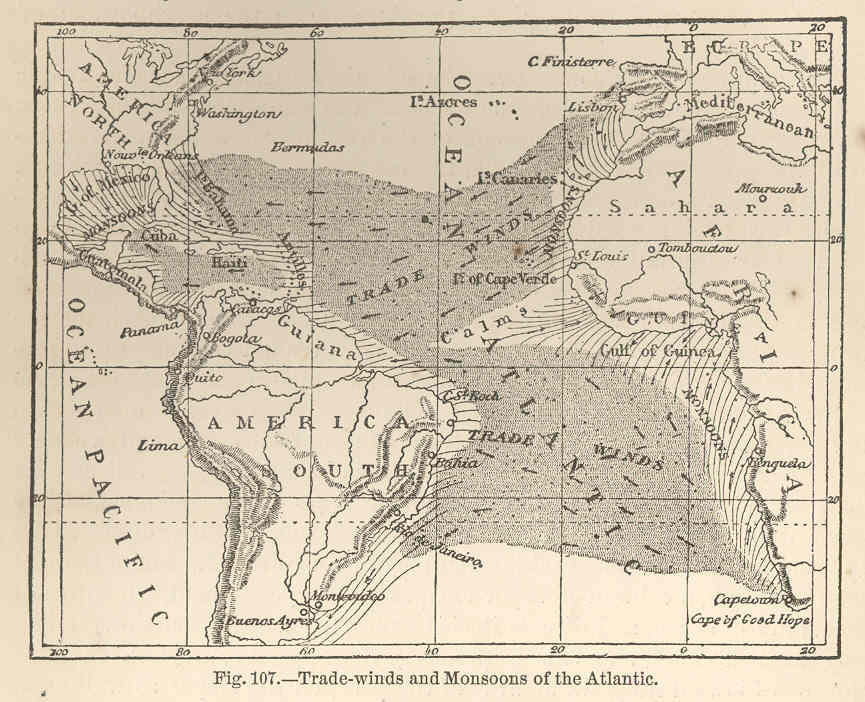

Featured Image: Élisée Reclus (1873) Ocean, Atmosphere, and Life, being the Second Series of a Descriptive History of the Life of the Globe, New York City, NY: Harper & Brothers, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.