By Gianamar Giovannetti-Singh

In 1645, the Manchus—a semi-nomadic population from northeast Asia—were cementing their control over the newly established Qing Empire. Near Fenshui Guan, a mountain pass between the southern Chinese provinces of Jiangxi and Fujian, Manchu soldiers came across a house decorated with a large red scroll that proclaimed: “Here lives a doctor of the divine Law who has come from the Great West.” Exhibited in front of the building were “European books, […] Mathematical instruments, telescopes, burning glasses,” as well as an image of Christ on the crucifix. Upon entering the house, the soldiers came across a bearded Italian, whom they immediately recognized as a Jesuit. Ever since the establishment of the Jesuit mission to China in the 1580s, the missionaries had presented themselves to successive Chinese imperial regimes as astronomical experts. By the mid-seventeenth century, their efforts had paid off, with Jesuits being readily identified by the Chinese and Manchus alike as astronomers. Instead of facing Archimedes’ fate, then, the bearded Italian was invited by the Manchu commander to join their side and provide astronomical and ballistics expertise to the Qing empire—an outcome he gladly accepted. So began Martino Martini’s service for the Qing regime, which ended up having an unexpectedly far-reaching impact on approaches to writing history in early modern Europe.

In imperial China, studying the heavens was inseparable from politics and statecraft. The emperor, considered the “天子 tianzi,” or “Son of Heaven,” required the “天命 tianming,” or “Mandate of Heaven,” to rule legitimately over the empire, referred to as “天下 tianxia,” meaning “All Under Heaven.” If Heaven was pleased with the conduct of a particular emperor or dynasty, it would demonstrate its satisfaction by not deviating from the celestial forecasts made by court astronomers in the official calendar. If, on the contrary, Heaven had lost its confidence in a ruler, it would manifest its discontent through “天災 tianzai,” or “calamities from Heaven,” such as earthquakes, droughts, and unforeseen eclipses, damaging the incumbent’s imperial authority. Unsurprisingly, Chinese emperors had long employed skilled astronomers in astronomical bureaus to publish calendars that accurately forecasted eclipses, which would in turn grant the emperor political legitimacy. Given astronomy’s crucial importance in imperial politics, Chinese historical annals since at least the early second millennium BCE included systematically recorded celestial observations alongside political and social events.

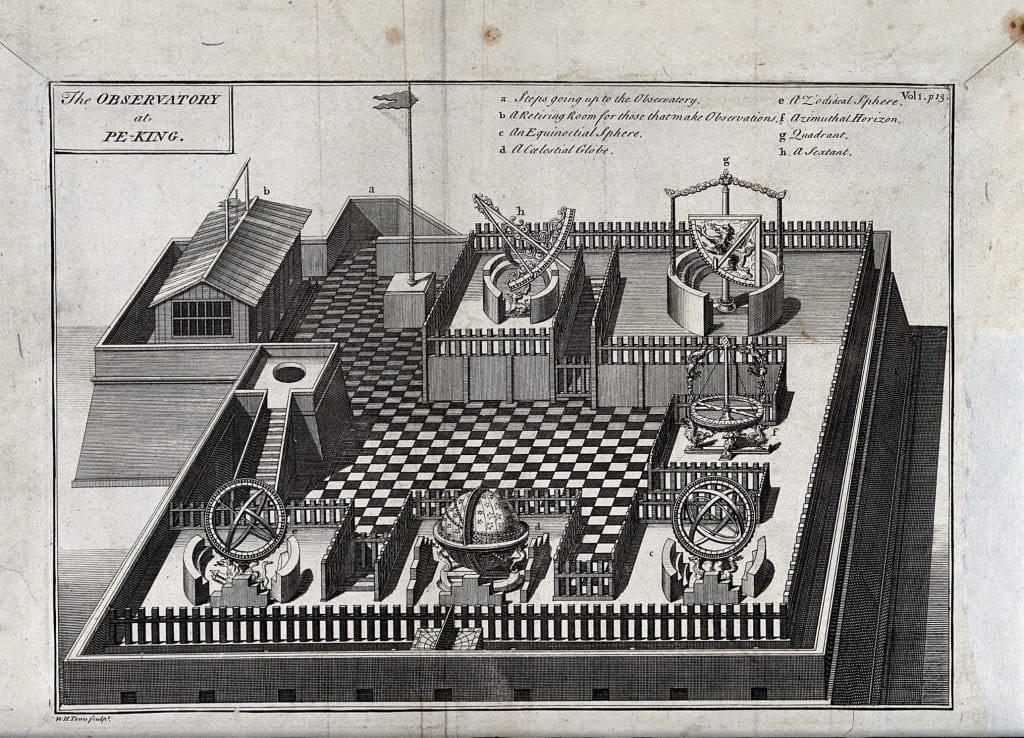

As Martini reached Ming China in 1643 after a long and arduous voyage from Lisbon, the empire was facing its most severe and protracted series of calamities from Heaven for several centuries. The famines, epidemics, and plagues of locusts that afflicted the troubled empire spurred popular rebellions against the Ming dynasty led by charismatic peasant leaders, as well as ever-deeper incursions into imperial territory by the Manchus from northeast Asia. In other words, the Ming were losing their Mandate of Heaven, which was now up for grabs. Entering a profoundly crisis-stricken, socially, and cosmologically damaged polity, rival claimants of the Mandate considered Jesuits like Martini to be invaluable assets to have on one’s side. Having been recently involved in the Gregorian calendar reform in Europe, the Jesuits were well placed to serve as court astronomers and calendar-makers and so could help legitimize their respective claims to the Mandate of Heaven. In 1644, after conquering the imperial capital Beijing, Dorgon—the first regent of Qing China under the Shunzhi emperor—had appointed the German Jesuit Johann Adam Schall von Bell as director of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau in Beijing, making him responsible for issuing the official annual calendar. Schall von Bell’s astronomical labor for the Manchus helped cement their Mandate of Heaven to rule over China.

In 1650, a few years after his encounter with Manchu soldiers in southern China, Martini was sent to Beijing to work with his fellow Jesuit, Schall von Bell, in the imperial astronomical bureau. Although Martini did not stay there long, his time at the bureau—where he would have collaborated with Chinese astronomers, observing and interpreting the skies—helped him see Chinese and European astronomy as fundamentally compatible, even though he maintained the superiority of European mathematics. It is also likely that it was during his time in Beijing that Martini came across the historical works that provided the evidence for his later claim that Chinese annals contained “the record of many astronomical observations, which date back to times in the proximity of the origin of the world, more ancient than those made by Dionysius, Eratosthenes, or Hipparchus.” Through his experience of the violent Ming-Qing transition, in which he used astronomical diplomacy to escape a tricky political situation, Martini came to acknowledge the inseparability of politics and the heavens in China. This realization of the connections between politics and astronomy led Martini to conclude that “the most ancient observations of the stars […] written in the most ancient [Chinese] volumes” formed an excellent, systematic bedrock for historical scholarship.

In 1651, Martini began an eventful journey back to Europe, which saw him arrested by both the Sultan of Makassar, whom the Jesuit claimed to have “conquered […] with the art of mathematics,” and the Dutch East India Company, which gleaned valuable geopolitical knowledge of the new Qing empire from him in a Batavian prison. The Dutch in Batavia—a city also settled by several thousand Chinese merchants—were keen to learn as much as possible about their trading partners and the new Chinese government. Martini’s intelligence on the Qing regime’s foreign trade policy saw him rewarded with free travel back to Europe on a Dutch ship. After landing at Bergen in 1653, the missionary embarked upon five years of travels across Europe, lecturing and publishing extensively about China. Martini met several important political, scholarly, and commercial figures, including Pope Alexander VII, Joan Blaeu, his old teacher Athanasius Kircher, Isaac Vossius, and Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, hoping to raise funds and sympathy for the Jesuit China mission. In 1658, as he began his return trip to China after a productive period in Europe, Martini’s final book, Sinicae Historiae Decas Prima, was published in Munich. In this work, Martini made the striking claim that China, the “extreme part of Asia […] was populated before the Flood” and that one could reconstruct its history using its lengthy and systematic astronomical records.

On the one hand, the missionary’s reliance on celestial sources to write history fit well into the early modern European discipline of technical chronology, as practised by Petrus Apianus, Heinrich Bünting, Paulus Crusius, Johann Funck, and—most famously—Joseph Justus Scaliger. On the other hand, Martini’s book argued that ancient Chinese astronomical records were older and more assiduously documented than their Greco-Roman or biblical counterparts. A controversial consequence of his argument was that if Chinese observations of the heavens stretched back to before the Deluge, and if there was continuity in the practice of Chinese astronomy before and after the Flood, then Chinese astronomy may offer better insight into antediluvian divine wisdom than its “European” equivalents. Such reasoning threatened Christian narratives about human history, calling the Bible’s authority into question. Thus, it’s not surprising that the Jesuit’s claims about Chinese astronomical chronology were appropriated and redeployed by freethinkers and secular philosophes in Europe, from Isaac Vossius to Voltaire.

In his Essay on Universal History (1756), Voltaire rehashed Martini’s claims about Chinese history for his own, secularizing political purposes, stating that “the Chinese have joined the celestial to the terrestrial history, and thus proved the one by the other. Their chronology, according to testimonies that are judged authentic, uninterruptedly ascends two thousand and thirty years […] so high as the emperor Hiao [Yao], who took some pains himself to correct their astronomy.” A decade later, contributing an entry on “History” to Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1765), Voltaire once again promoted Chinese astronomical records as an historical resource. The philosophe maintained that one of the most “incontestable monuments” with which historians could reconstruct the past was “the complete eclipse of the sun calculated in China two thousand one hundred and fifty-five years before the vulgar era, & recognized as true by all our Astronomers.” To a secular campaigner like Voltaire, Martini’s claim—that Chinese astronomical records formed an excellent basis for writing “world history”—appeared too good to be true. The French philosophe was able to cite a Catholic missionary’s work as evidence against Christian sacred histories, such as the Irish archbishop James Ussher’s chronology in Annales Veteris Testamenti, which instead relied on a literalist textual interpretation of the Old Testament.

The eighteenth century saw intense controversies in Europe over how to most credibly reconstruct the deep past. Sir Isaac Newton, for example, used ancient Greek astronomical records to write his controversial The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728). One of the issues at stake was whether ancient astronomical observations were as accurate and reliable as contemporary ones—a discussion that intersected with the ongoing Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns. These disputes, taking place in European scholarly academies, etched out the contours of a new, modern “cultural history,” which gradually replaced biblical universal history during the Enlightenment. Through their ability to destabilize received views about the accuracy and reliability of non-European astronomy, the Chinese astronomical records that Martini and his confrères brought to Europe created quite a splash in Enlightenment debates over historical scholarship.

Ultimately, then, Martini’s astronomical chronology of China, which was profoundly shaped by his experience of the Ming-Qing transition and the political expediency of engaging in Chinese astronomy in early Qing China, ended up transforming Voltaire’s—and, many other continental Europeans’ “Enlightened”—approaches to historical scholarship. Even though he almost certainly appropriated Chinese chronology as a tool with which to undermine Christian sacred history, Voltaire promoted what, at first glance, appears to have been a more “scientific” and “modern” historical method than Ussher’s biblical exegesis. Nevertheless, this shift in practice did not occur due to a “modernizing” spirit. It happened because it was in different actors’ interests—Martini’s in turbulent interregnum China and Voltaire’s in Bourbon France—to promote Chinese astronomical records as an historical resource. The entanglement of a “European” scholarly discourse, like secular world history, with events, practices, and peoples on the other end of Eurasia, should complicate the simplistic progressivist narratives about the modernization of history as a discipline.

Gianamar Giovannetti-Singh is a PhD candidate in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. His doctoral research examines how the Manchu conquest of China in the 1640s transformed the sciences in early modern Europe. This think piece accompanies Gianamar’s forthcoming article in the Journal of the History of Ideas, ‘Astronomical Chronology, the Jesuit China Mission, and Enlightenment History’. Twitter: @gianamar97

Edited by Tom Furse

Featured Image: Portrait of Martino Martini by the Flemish painter Michaelina Wautier, 1654. Oil on canvas. Wikimedia Commons.