By Rebecca Goldsmith

Commentators on the left have long looked to the past to better understand politics in the present. In 1982, for example, Raphael Samuel and Gareth Stedman Jones called upon their contemporaries to ‘think[…] about the Labour Party in a historically informed way… beyond cliched generalities.’ Since 1982, this call has, to a considerable extent, been heeded. In recent years, this has manifested in the tendency to move beyond glorified milestones like 1945, shrouded in myths of Labour’s ‘golden age,’ and to revisit and reappraise alternative past political landscapes, like the 1930s. Jon Cruddas’ 2013 George Lansbury memorial lecture drew upon the ‘rediscovery’ of the interwar Labour leaders to advocate for ‘exiled’ Labour traditions, calling for the party to “return[…] to question of ethics and virtue… issues of principle and character.” Patrick Diamond compares Labour’s economic policy formation across the 1930s with Labour’s experience following the 2008 financial crisis to Jeremy Corbyn’s election as party leader. While contributing to a deeper and more expansive chronological account of Labour’s past, such accounts continue to fall into the ‘internalist’ trope of Labour Party history, characterized by a concern with questions of parliamentary leadership and policies. I want to use the space here to suggest that alternative questions and, potentially, alternative lessons can be drawn from the 1930s.

Attempts to draw ‘lessons’ from the past must always involve a recognition of change over time. Given the dramatic transformations in political culture, identities, and structures that have taken place since the 1930s (the emergence of ‘national’ politics and the declining political salience of ‘class’ for example), considerations of this decade must proceed with particular caution. Despite these differences, there are intriguing similarities between the two periods. Crucially, in the 1930s, as today, Labour faced the question of how to win working-class support amidst rising prices and a cost-of-living crisis. Turning to the popular politics of the 1930s, analyzing the relationship between Labour candidates and the electors they sought to represent, can help to shed fresh light on the challenges Labour faces in the present.

***

My doctoral research centers on the Labour Party’s shifting relationship with the working class in the mid-twentieth century. Bolton, a Lancashire mill-town in the North-west of England, forms one of the case studies for my project. Using archived field notes from the experimental social-science research organization, Mass-Observation, I place Labour’s official platform in Bolton, its appeals to local workers, in dialogue with the testimony of the workers themselves. Doing so suggests that, amidst rising unemployment, increased taxes and prices, the local Labour Party ran up against the attitudes and impulses that arose from popular experiences of these conditions.

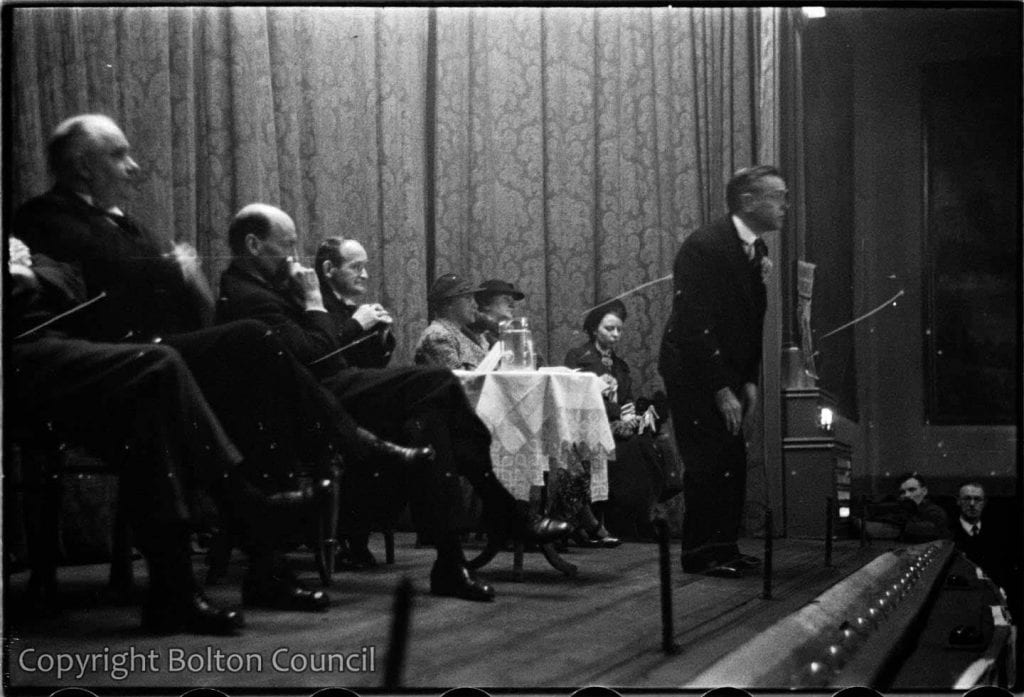

The Labour Party in Bolton responded to worsening socio-economic conditions by centering its platform on the widespread conditions of unemployment, poverty, and hunger facing local workers. At one Bolton Labour Party ‘Crusade’ meeting in November 1937, the local Party Chairman Tom McCall emphasized that Labour councilors had ‘done all that is humanly possible to improve the lot of the poor,’ referencing especially their work on the Public Assistance Committee.[1] At this meeting, the visiting speaker referenced local experiences collecting ‘your miserable money at the Employment Exchange, or at the PAC’ (WC 7/B/81). This strategy targeted inner-city wards, with higher levels of overcrowding and infant mortality rates, regarded as traditional Labour strongholds. Yet, Labour lost these strongholds in the late 1930s, largely to the Conservatives. Popular testimony suggests these losses may have stemmed from the local party’s failure to reckon with the considerable stigma surrounding unemployment and the subsequent limited appeal of being mobilized around the experience of it. Eric Letchford, an unemployed ex-iron miller, authored a report entitled “class distinctions in our street,” in which he confessed that he was “positively at the bottom of the social scale, very few people living around me have time for me and my children are often told to go away from other people’s houses” (WC 44/F/589). Letchford’s testimony relays the stigma surrounding reliance on unemployment relief, reinforced by his reference to one neighbour who “once had a long period of unemployment and attempted to gas himself” (WC 44/F/590). His report provides unique access to the similar feelings of shame hinted at in letter pages in the local press.

More generally, turning to the attitudes of local people suggests, on these terms, working-class support for Labour in Bolton came to be associated with a politics of charity and relief. Residents relayed their perception of the party as ‘always for the poor,’ reinforced by overheard jokes about voters switching in allegiance from Labour to Conservative upon buying a house (WC 11/E/476; 7/B/142). When placed alongside the heightened divides between ‘rough’ and ‘respectable’ in 1930s Bolton, such comments may help to contextualize the popular reluctance to be associated with the party. This reluctance was met by street canvassers, in their reports of those who “come[…] to the door – smiles – when I mention Lab: Oh! No not here,” and in the descriptions of local individuals who were ‘Labour’ but “do[n’t] shout about it” (WC 11/B/64; 11/I/609). This association of Labour with a politics of charity was exacerbated by the lingering influence of Christian non-conformism in Bolton Labour politics, manifested in Labour councilors’ emphasis on needing to “improve the lot of the poor,” calling for the provision of libraries and art galleries while condemning ‘selfishness’ (WC 7/B/64-66). This treatment of local workers as objects of charity could backfire. Where local Labour politicians referred to the ‘unfortunate unemployed’, this could provoke feelings of ‘resentment,’ as described in the autobiographical writings of Alice Foley, a Bolton-born Trade Unionist (WC 7/B/56, See Alice Foley Collection).

Such evidence suggests that language, the terms upon which workers were included in politics, mattered. Relatedly, where local Labour activists framed workers’ interests around their immediate, material needs, this encouraged a deterministic understanding of working-class political behaviour. The party chairman, for instance, complained following a poor municipal election showing that local workers “failed to register votes for the class to which they belonged” (WC 7/B/63). Moreover, one of Labour’s unsuccessful candidates for East Ward in Bolton attributed his defeat to “the fact the electors are ‘like a lot of rabbits’” detailing one man who refused to be rehoused along with his large family to a new housing estates, since he was “entirely satisfied with the paperless walls and bulging ceiling,” suggesting “its people’s environments make them vote the way they do” (WC 11/I/592), This comment reinforced the idea, expressed elsewhere in interwar Bolton, that working-class perspectives were defined by and limited to their immediate environment. The Mass-Observation Archive, however, reveals popular efforts to disprove this idea. Bill Rigby, a local, unemployed ex-miner, composed a report about life on his Bolton Corporation Housing Estate. Rigby argued that where working-class residents on the estate displayed a ‘pride in living + appearance,’ this stemmed from a pre-existent impulse which “in the previous house, flat or rooms, had no room for expression” (WC 44/A/12). Rigby thus sought to claim respectability as an authentic working-class trait rather than one produced by a new environment. Moreover, he sought to correct the “popular conception of certain sections of the public that working-class tenants of the estate do not avail themselves of their new amenities.”

Rigby’s account speaks to broader popular efforts to defend working-class respectability. This can be seen in the testimony collected by an unemployed recruit volunteering for Mass-Observation in Bolton, Peter Jackson, who asked local people why they made bets on the football pools. His responses reveal the aspirations and dreams held by local workers, which they hoped to realize through the pools, from wanting to start businesses in Blackpool to “‘breedin’ budgies on a big scale” (WC 4/F/433). But, most strikingly and recurringly, across their interview responses, individuals rooted the appeal of the pools in the chance it offered to achieve financial independence. Their dreams of leaving Bolton, whether by moving to ‘South Africa’ or relocating to ‘the Midlands’ reveal their frustrations with and desires to extend beyond their current horizons (WC 4/F/416, 432). The politics of relief pursued by Bolton’s Labour Party left little scope for recognizing workers in these terms as individuals with ambitions and aspirations. By contrast, Conservative candidates in Bolton mobilized a politics of experience, rooted in place, which enabled them to speak in more respectful, empathetic terms. Where Labour referred to the “unfortunate unemployed,” Conservative candidates discussed the “evil of unemployment,” refusing to define local workers by their current circumstances, instead addressing them as “men and women out of work” (WC 11/E/424, 419).

Such analysis affords a better understanding of Labour’s struggles in 1930s Bolton and suggests the critical importance of the relationship between popular attitudes and ideas and the language deployed by local activists in their appeals. This is demonstrated further by an alternative instance where Labour successfully mobilized working-class support, against severe economic circumstances, in the neighboring constituency of Farnworth. Labour’s candidate in the 1938 Farnworth by-election was George Tomlinson, a previous union official, a Methodist preacher, and half-timer (children who split their time between work in the factory and school). Throughout his campaign, Tomlinson articulated a politics of experience, referencing the harsh realities facing local workers. Tomlinson “spoke to the audience in terms of their own lives,” feeding into his moving, sympathetic discussion of the ‘insecurity’ that “gnaws at the heart strings of the working classes,” mentioning his own father’s inability to take a holiday as he “couldn’t stay off work,” living a working life of “constant fear” since he could “never afford to be ill” (WC 7/B/144, 149, 160, 161). He described his mother’s anxiety at holiday time when the family’s lack of income meant “she ‘ad [sic] an impossible problem to solve” (WC 7/B/161).

In this way, Tomlinson was able to articulate the psychological burden (shared by men and women in Bolton, an area of high female employment) of workers’ struggles to ‘manage’ amidst the increased cost of living, evident in popular complaints that “no one can really enjoy their holiday and get the best out of it unless they have no worries’ and ‘lack of funds prevent this” (WC 46/B/7, 67). The ‘holidays with pay’ campaign formed a central part of Tomlinson’s platform, building on these feelings and affording workers a sense of dignity, seen in Tomlinson’s emphasis that this was a question of ‘entitlement,’ rather than charity (Bolton Evening News). In this way, Tomlinson affirmed workers’ frustrations with their current restricted horizons, seen in his suggestion that “I sometimes think we don’t ask for enough” (WC 12/H/433). Ultimately, this appeal to politics of experience was reinforced by the centrality of place in Tomlinson’s platform. By appealing to place, Tomlinson aligned himself more closely with the specificities of local classed experiences, emphasizing that his Tory rival, a London barrister, could not “represent you as well as I could… not knowing your daily life” (WC 12/G/341-2). The effectiveness of this appeal is evident in overheard appraisals of Tomlinson, suggesting “he’s lived ‘ere so long and done lots of good work – people don’t forget that” (WC 7/B/174).

***

Overall, this impression of Labour politics in the 1930s resonates with the current political problems facing the Labour Party. Amidst the ongoing cost of living crisis, Labour faces a similar challenge of how to reckon with the hardships facing local workers while avoiding any negative, stigmatized associations with a politics of charity or being seen on sectional terms as ‘the party of the poor.’ Today, too, Labour faces the question of how to speak to ordinary people’s struggles to ‘manage’ amidst rising prices and falling real wages while retaining recognition of their respectability and affording a sense of dignity. The critical differences in political culture between the 1930s and the present, elaborated above, encourage caution in drawing ‘lessons’ from the past for politics today. Yet, if we tread speculatively, historical analysis can speak to current circumstances. For example, the evidence considered here reflects the importance of the relationship between Labour’s platform, the terms upon which workers are included, and the impulses and attitudes arising out of popular experiences of everyday life. This is not so much about deploying a series of abstract nouns, like ‘family’ or ‘respect,’ but speaking to people ‘in terms of their own lives,’ recognizing and understanding the emotional and psychological impact of experiencing these conditions.

Recent media releases suggest that the Labour Party today is moving in this direction, seen, for instance, in its leader, Keir Starmer’s recent reference to ‘people from my background.’ Yet, the analysis above suggests the productive nature of place as a tool for tapping into popular ‘structures of feeling.’ The significance of ‘the local’ to popular experiences of politics has, admittedly, declined amidst the emergence of ‘national’ politics in the years since the 1930s, and the crisis we face has its roots in global, transnational forces. Yet its impacts are felt locally. Labour needs to be able to speak the effects of the current crisis, as well as its causes. The geographically uneven ways in which people experience inequality suggests the party needs to think more seriously (beyond the often-crude archetypes and quantitative data offered by polling) and more locally, about how it responds to the current cost-of-living crisis.

[1] Mass-Observation Online Archive [MOA], Worktown Collection [WC], Box 7: Party Politics, File B: Labour Party, 64.

Archival materials cited:

Mass-Observation Online Archive (MOA), Worktown Collection (WC), Boxes 4 [Sport], 7 [Party Politics], 11 [Municipal Elections], 12 [Voting; Parliamentary Elections], 44 [Social Condition and Housing], 46 [Holiday Competition Questionnaire].

‘Pain of Social Adjustments: Our Street’ (undated), p.1, in ZF0/32: Alice Foley Collection – Workers’ Educational Association, Bolton Archives and Local Studies, Bolton.

See ‘Labour Opens Campaign,’ Bolton Evening News (15 January 1938), p.2. Bolton Evening News, held at the British Library.

Rebecca Goldsmith is a PhD student studying the Labour Party and the politics of class in mid-twentieth-century Britain at the University of Cambridge. She completed her MPhil thesis on popular political culture at the 1945 general election. She tweets @rebeccagold123

Edited by Tom Furse

Featured Image: 1: Image ref. 1993.83.01.22 Print ref. INV:15779 Updated: Jun 26, 2012 Page author: Bolton Museums [Horatio Street and Marsh Fold Lane]. 2: Image ref. 1993.83.15.20 Print ref. 1993.2.3 Updated: Jul 2, 2012 Page author: Bolton Museums [George Tomlinson]. Copyright granted.