By Gongchen Yang

After the British commutation of the tea tax in 1784, the British purchased £1.3 million worth of tea in Canton in 1786 and paid for nearly half of this in silver bullion rather than other export goods (p. 272). At the same time, the British manufacturers created a vast array of new British goods (mainly textiles) that needed an export market. The trade deficit created by the Sino-British tea trade and the potential of the Chinese market drove British policymakers and merchants to send an official embassy to China to improve the restricted trading environment.

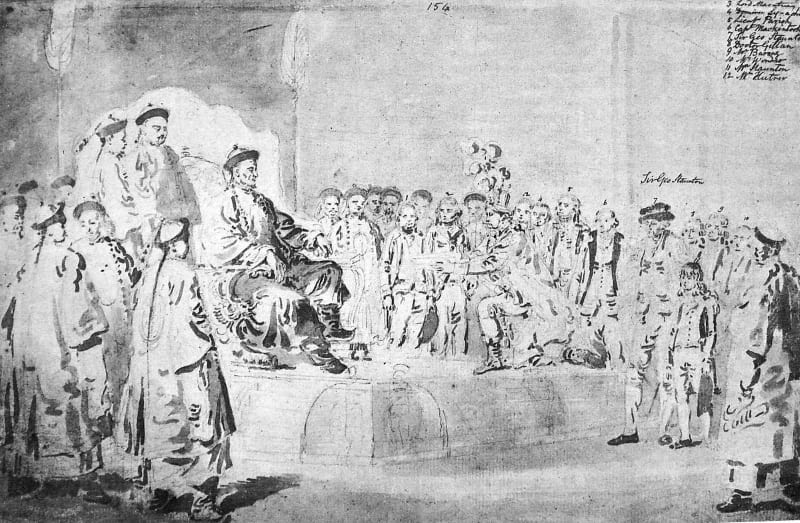

Earl George Macartney led an embassy to visit Qianlong Emperor in 1793 at his summer resort of Jehol (Rehe, now Chengde) to celebrate his 80th birthday. For the Qing side, the mandarin welcoming what is called ‘the Macartney embassy’ was Heshen (p. 288-290), the favorite Minister of the Qianlong Emperor. This was the first official encounter between Qing China and the British Empire. From the early Qing, many European missionaries served at the Qing court, offering their services in astronomy, mathematics, geography, and the arts. This think piece offers a ‘British-Sino diplomatic’ perspective on the further separation between China and the West after the Great Divergence, and it highlights the role of British and Chinese officials, Macartney and Heshen.

In the context of the Chinese tribute system, the wrong choice of gifts and Chinese officials’ filtering of information made the Mission’s attempts to demonstrate Britain’s technological superiority to the Qing court and to reverse its stereotypes fail. Eventually, the Qing court reinforced the original impression that the British were cunning and greedy for profit. The Mission brought back to the British Empire an image of the Qing Empire as “Gold and jade on the outside, rot and decay on the inside,” which significantly changed the British Empire’s perception of the Qing Empire.

The defeat of the American War of Independence at the end of the 18th century led the British Empire to pivot to Asia (p. 4, 6-7). As a commercial state, merchants were the most active and wealthy part of society and capital was of great concern to the government. At the same time, the British East India Company’s war with the Mysore Company (French ally) in South India also had dire prospects, war and territorial expansion nearly bankrupted the company. The British government sent an embassy to expand Sino-British trade to preserve EIC rule in India.

The victory in the Sino-Nepalese campaign of 1792 had given the Qing Dynasty remarkable military confidence. This campaign was the last of Qianlong’s Ten Great Campaigns (shiquan wugong 十全武功), which brought Gorkha (now Nepal) into the China-centered tribute system. The tribute system inherited from previous dynasties presumed the Middle Kingdom’s moral, material, and cultural superiority over other nations and required those who wished to deal or trade with China to come as supplicants to the emperor. Because the Qing court also tended to view maritime trade and traders as peripheral to its strategic and economic interests and as part of this manageable sphere, the European nations who came to trade at China’s ports were handled within this same tributary framework (p. 27-28).

Macartney had set high stakes for this Mission’s success. Among the European nations that traded with China, Macartney believed that “in consequence of irregularities committed by former Englishmen at Canton (like Lady Hughes Affair), Englishmen were considered as the worst among Europeans.” Therefore, believing that “the various important objects of the Embassy could be obtained through the good will of the Chinese,” Macartney ordered the Embassy to “impress the Chinese with new, more just, and more favorable ideas of Englishmen by a conduct particularly regular and circumspect” (p. 231).

Changing the Chinese ideas of the British became the key to the Mission’s success. Still, Macartney disagreed with the others about how to impress the most crucial person, the Qianlong Emperor. During the preparation phase of the Mission, the leading British manufacturers, like Matthew Boulton, wished to present products representing British industry as gifts to the Qianlong court. As a member of the Birmingham Lunar Society, Boulton conveyed the values of the Enlightenment and wanted to send buttons, buckles, plated wares, and other products that would make life more comfortable and of interest to Chinese consumers to China. In his letter to Macartney, King George III also demonstrated his desire to ‘communicate the arts and comforts of life to those parts of the world where it appeared they had been wanting.’ However, Macartney, a former diplomat to Russia, believed that ‘Asian courts would only be impressed by elaborate display, spectacle and pomp.’ Despite the aspirations of the manufacturers and the king, Macartney sent two coaches decorated in imperial yellow, an elaborate planetarium, and several luxury gifts (the introduction of gift, see p. 243-246).

Maxine Berg argued that Macartney’s Mission failed because the Embassy failed to express and convey the image of ‘useful knowledge’ to the Chinese ruling elite. And this probably stems from Macartney’s lack of knowledge of Chinese culture. Macartney was learning about China from works written by the early Catholic missionaries a hundred years earlier: knowledge of China’s recent court politics, which was crucial for diplomacy, was entirely absent (p. 69).

A few months before the embassy’s arrival, in June 1793 British and Chinese merchants in Canton submitted the official letters and translations of the embassy to the Beijing court in advance. The content of the translations is opaque and carefully avoids any clear statement of the embassy’s objectives, the main purpose of which seems to have been to bring birthday wishes to the emperor (p. 90). Once the embassy arrived in Chinese waters, officials conveyed a simple but misleading message to the Beijing court: Britain was showing deference to China by offering tribute to celebrate the emperor’s birthday. But Qianlong was not blind to these British visitors, he watched the Mission’s every move and had his favorite courtier Heshen, receive it.

The embassy arrived at Jehol in September 1793, but the supremacy of Chinese imperial power restricted Macartney’s communication with the Emperor. Apart from the Emperor’s birthday and a few necessary ceremonies, Macartney had no access to Qianlong. However, the exhibition of technology prepared by Macartney, who did not know the tribute system, angered Qianlong even before it was shown to him. Before arriving at Jehol, Macartney requested that four British artisans be sent to the royal palace to install the large planetarium, which would take a month. However, Qianlong believed that Chinese artisans could complete the installation and refused Macartney. After that, Macartney still stressed that this was a job only British artisans could do, leading Qianlong to believe that the British liked to show off. After they failed to impress the Emperor, the courtiers led by Heshen were the Mission’s last hope.

I argue that Macartney used close personal relationships to gain important political positions (p. 28-30), whereas Heshen’s promotion was more based on personal ability. With excellent language skills (Manchu, Mandarin, Mongolian, and Tibetan) and financial management skills, Heshen spent four years entering the Grand Council (junjichu 军機处), which is the chief policy-making body of the Qing court, at the age of 27, with members’ averaging age around 60. In 1786, at the age of 37, he was awarded the highest position in the Qing bureaucracy system and built a powerful political group under the emperor’s patronage. Investigating Heshen’s career path shows that the secret of his success was to please the Emperor, who could decide his fate. His interests were tied to Qianlong and his benefit. When Qianlong liked poetry, he then studied poetry so he could co-compose poems with Qianlong. When Qianlong liked calligraphy, he imitated Qianlong’s handwriting and could write on his behalf.

It was Heshen’s code of conduct to ‘side with the emperor,’ so he could not display too much interest in British technology. But Heshen’s pragmatism led him to display an ambivalent attitude towards British technology. On December 3, 1793, Macartney wished to show Heshen the latest European technology for hot air balloon ascension. Frustratingly, Heshen “not only discourage this experiment, but also the printed accounts of British empire that they prepared for Chinese courtier.” However, when suffering from hernia and rheumatism, the embassy’s doctor Gillan was sent to treat Heshen with western medicine (p. 321). Thus, had British technology been of visible benefit to him and his emperor, Heshen would have taken the initiative to learn about it and try it out.

Interestingly, Macartney’s inappropriate choice of British gifts may have been right for the future expansion of the British Empire in China, as transformative British technology could have been ‘stolen’ by China. For instance, Macartney decided not to take a steam engine, the emblematic technology of the Industrial Revolution. It may have impressed the Qianlong court. But it also risked being ‘stolen’ by Chinese artisans, who were talented in arts and crafts and had advanced technology. According to Mr. Barrow of the embassy, two Chinese artisans could “separated two magnificent glass lusters piece by piece and put them again together in a short time without difficulty and mistake, the whole consisting of thousand pieces, though they had never seen anything of the kind before” (vol.2, p. 98). Secondly, Qianlong intended to have Chinese artisans learn British technology. For the large planetarium, Qianlong sent two Chinese artisans to learn the skills of installation and repair (vol.19, p. 157). At this moment, Qing China lost the possibility of learning some transformative industrial and military technology.

Macartney had six demands: granting British merchants access to the Chinese market through Chusan (now Zhoushan), Ningpo (now Ningbo), and Tientsin (now Tianjin); to warehouse their goods in Pekin (now Beijing); owning a secure island for their unsold goods in Chusan and Canton; abolish trade duties between Macao and Canton; and prohibit all duties on English merchants over the Emperor’s diploma (see Canton System). For Embassy’s commercial demands, Heshen avoided discussing them with Macartney as much as possible and concealed these ‘excessive’ demands from the Emperor to avoid angering him. For many in the imperial court, these demands insulted the emperor’s dignity and, more practically, the empire’s stability.

While European missionaries stayed and served at the court in Beijing at the cost of not leaving China until they died, British Empire wanted to set up a permanent embassy compound in Beijing and to have some territory to live in. Macartney’s first meeting and commercial negotiations with Heshen took place a week before the Emperor’s birthday. It was not until after his birthday that the Emperor learned of the Mission’s commercial requirements through Heshen. Macartney could do nothing about Heshen’s evasion, saying, “I could not help admiring the address with which the Minister parried all my attempts to speak to him on business this day, and how artfully he evaded every opportunity that offered for any particular conversation with me, endeavoring to engage our attention solely by the objects around us.”

Other possible ways of impressing the Chinese were military exhibitions, but the information filtering by lower-ranking officials prevented the impact of military exhibitions from reaching the emperor. Macartney’s warship, the Lion, was the height of contemporary military technology (p. 73), but Chinese official reports stated that the Lion was simply a tribute ship. No one dared to truthfully report how the warship was a military threat or its advanced technology. Yet according to Macartney’s observations, “these mandarins had never seen a ship of the Lion’s construction, bulk, or loftiness. They were at a loss how to ascend her fides; but chairs were quickly fastened to tackles, by which they were lifted up, while they felt a mixture of dread and admiration at this safe, rapid, but apparently perilous, conveyance.” (p. 240). Poor translation skills meant no fruitful conversation about the Lion and naval warfare occurred.

The Mission left Beijing on October 7, 1793. Qianlong sent several senior officials to accompany the Mission and report on all its movements. At the same time, Qianlong ordered the officials in Canton and Macau to prevent the British merchants from monopolizing trade and conspiring with foreign traders. Eventually, Macartney’s efforts to “impress the Chinese with new, more just, and more favorable ideas of Englishmen” failed, and the Qing court reinforced the original idea that the British were cunning and greedy for profit. In Macartney’s view, Qing China was not as strong economically, militarily, or technologically as it should have been. The Qing Empire was, in fact, “Gold and jade on the outside, rot and decay on the inside.”

Gongchen Yang is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Warwick. His doctoral research focues on the corruption of the Canton customs in Qing China. His general interests include corruption, Chinese maritime customs, and Sino-British interactions.

Edited by Tom Furse

Featured Image: Lord Macartney’s Embassy to China 1793. Creative Commons.