By Shuvatri Dasgupta

The workshop “Citizen/Stateless Person/Cosmopolitan: Refugee Selfhood in Global Intellectual and Legal History” was held at the University of St Andrews on 9 September 2022. It addressed the dearth of academic engagement with the question of global refugee selfhood in the long 1940s, intersecting perspectives of global intellectual history and legal history. It was co-organised by Kerstin von Lingen (Vienna) and Milinda Banerjee (St Andrews). The workshop received generous financial support from the University of Vienna. It received additional financial and logistical support from Caroline Humfress (St Andrews) and the Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research, University of St Andrews. The workshop drew part of its inspiration from the journal Itinerario’s special issue “Forced Migration and Refugee Resettlement in the Long 1940s” (Vol. 46, August 2022) co-edited by Banerjee and von Lingen. In its introduction, they argue that the long 1940s witnessed a “global refugee resettlement regime”. The emergence of a global refugee subjectivity was one of the major outcomes of the political conflicts of the mid-twentieth century. Nation states and international organizations debated questions of citizenship, displacement, resettlement, and statehood. However, within global histories of the twentieth century, the figure of the refugee continues to remain marginalised. In fact, the lens of transnational and global history has only recently been applied to the study of twentieth century partitions. Given the specificities of area studies research, historians have also not traced the connected nature of these histories. The papers in this workshop all addressed this crucial research vacuum in modern global history.

How did refugees conceptualise their displacement? Were the grammars of citizenship and political belonging within a nation state important to them? Which categories and ideas do they implement in shaping their global selfhood? These are some of the questions which Dina Gusejnova (LSE) and Milinda Banerjee (St Andrews) addressed in their papers on refugee political thought. Gusejnova cast an eye towards the Baltic German nobility seeking refuge from the violence of the Russian Civil War in the early twentieth century. Her paper analysed the works of international lawyer Mikhail von Taube, a member of the Baltic German aristocracy, who left Russia in 1917 and settled in Paris. As a member of a “community of imperial internationalists” Taube had a “cosmopolitan yet uprooted” subjectivity as a refugee. In shaping this consciousness, Antigone became his spokesperson. Gusejnova located this choice within a broader context of Antigone’s revival in mid-twentieth century Europe, especially in the works of Alexandre Kojève, who was influenced by Hegel. For Hegel, Antigone embodied a moment of unhappy consciousness in the dialectic between the family and the state. For Taube, she did just the same. Antigone became a suitable mouthpiece for Taube’s unhappy consciousness as a refugee in Paris, alienated from his lineage and kin and marginalised by the Bolshevik Russian state.

In Banerjee’s paper, this unhappy consciousness of the global refugee found resolution through critiques of capitalism. He considered Bengali Hindu refugees migrating from east Bengal/Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to the Indian state of West Bengal in India, following the Partition of 1947. Banerjee drew on state archives, refugee memoirs, novels, poems, short stories, and movies, demonstrating that refugee political consciousness was resolutely transnational. In the context of the Cold War, Communist-influenced refugees employed Marxian categories of political economy, such as money, property, value, and wage, to critique the bourgeois state and capitalist landlordism. High-caste refugees often fashioned themselves as “new Jews”, comparing their plight with Jewish experiences of displacement. Lower-caste/Dalit refugee thinkers drew on Hegel, Marx, and Black radical theory to critique caste/class-inflected proletarianization of refugees. Banerjee argued that these Bengali actors produced new models of refugee republicanism and created new practices of refugee democracy that led to the consolidation of Left governance in the region. Ultimately, both Gusejnova and Banerjee centered refugees as political thinkers, and placed them at the heart of global intellectual history.

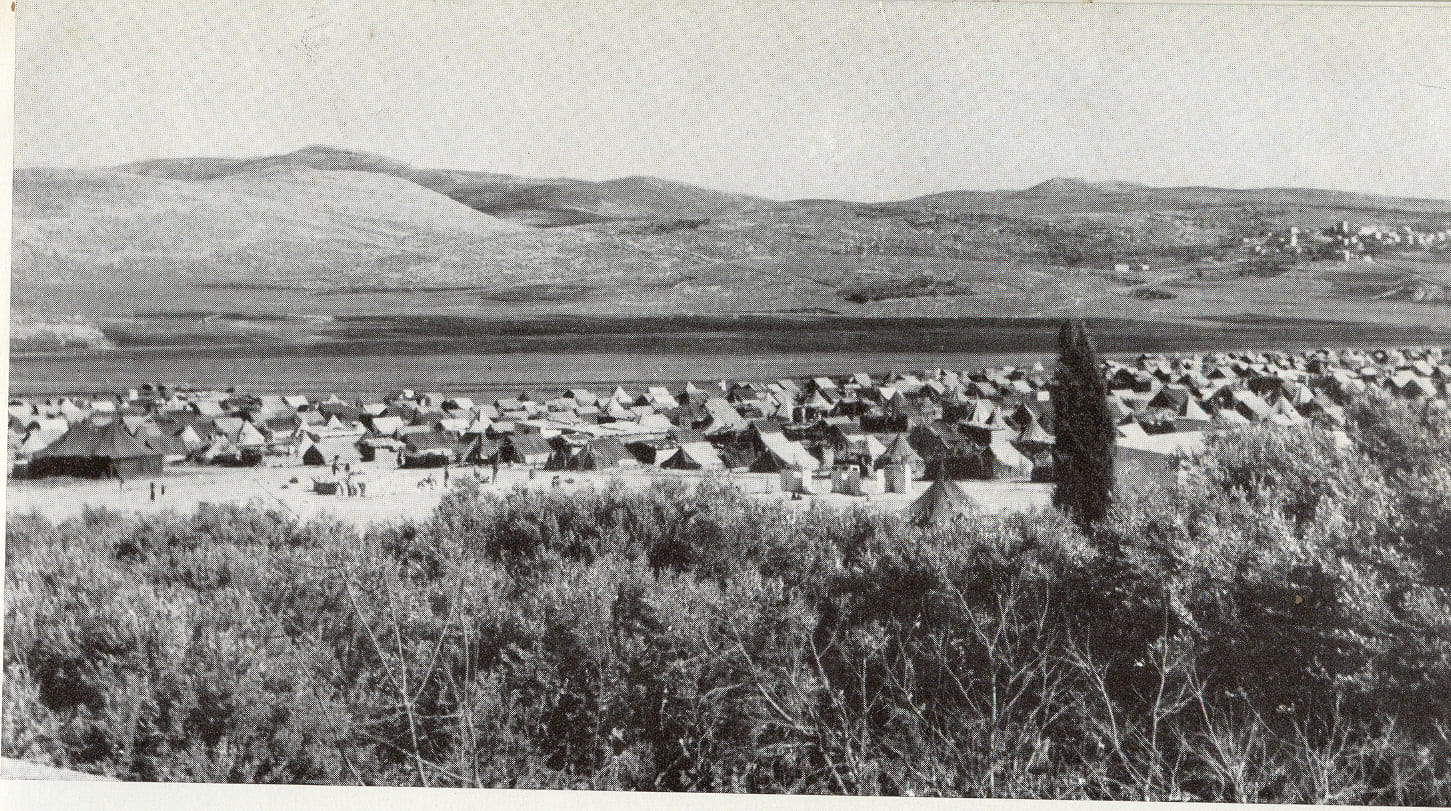

Shaira Vadasaria’s (Edinburgh) paper addressed the refugee question in the context of Palestine, deploying the lens of racial politics and settler colonialism. She scrutinised the Balfour Declaration of 1917 as paving the way for settler colonialism in the twentieth century. She traced the ways in which British Mandate powers denied Palestinian subjects their nationhood and showed how Zionist leaders cast Palestinians as “subjects of racial difference”. She illustrated how humanitarian aid was prioritised over land repatriation by the United Nations. This move condemned Palestinian refugees to a state of eternal waiting, relegating them to “a life of return amidst extraterritoriality”. Khaled Hosseini in his novel “A Thousand Splendid Suns” wrote, “Of all the hardships a person had to face, none was more punishing than the simple act of waiting”. For him, the act of waiting defined the state of being a refugee: waiting for loved ones to return, for migration related paperwork to come through, and for an elusive opportunity to return home. Vadasaria mapped the poetics of this affective ontology of waiting onto the Palestinian refugee selfhood after the Nakba.

For only some Viennese Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, waiting came to end after the Second World War with their return to Vienna. However, it was not the same home that they had left behind. Kerstin von Lingen’s (Vienna) paper narrated one such story of loss and return, contextualised within “the complex practices of resettlement” in post-war Europe. The Nazi state revoked German citizenship for Jews and confiscated their properties, following the Nuremberg racial laws in 1935. This marked the beginning of their “expropriation and pauperization” by the state. As the situation worsened, Jews prepared to leave Germany. Since they were emigrating, they shifted these moveable properties to Italian port town, Trieste. However, Nazi legislation stated that Jews were not entitled to move goods after being denaturalized as citizens, and thus the property got stuck in Trieste. As a result, the port authorities complained to the Nazi government. In response, still during the war, these boxes were shipped to Klagenfurt in South Austria, and put to re-use by the known auction company “Dorotheum”. Subsequently, German citizens incurred massive losses during the Allied bombings. Now, the Nazi government sorted and redistributed these things. Therefore, the goods changed hands from Jewish refugees to German citizens. After the Second World War, British troops came to Klagenfurt and found 8000 moving boxes containing more than 2000 household goods. After the refugees returned to Austria, they claimed their citizenship and property, but to no avail. Since the famous legal battle about the famous painting ‘The Golden Girl’ by Klimt, there is growing awareness in Austria to remedy these wrongs. However, majority of the goods remain lost. Von Lingen concluded that we must center Viennese Jewish refugees within wider transnational histories of loss of citizenship and property.

Whilst some Jewish refugees returned to Austria, others sought to resettle elsewhere and build new lives. Philipp Strobl, in his paper, studied one such instance of Jewish refugees migrating from Nazi Germany and settling in Australia. How did they carve out a space of their own in a new land? What challenges did they encounter? How were migration regimes negotiated? How did post-war politics shape their selfhood? During the late 1930s, Jewish refugees fleeing from Nazi Germany arrived on the shores of Australia. Their growing numbers became a concern for Australian policy makers. The political climate in the country remained unfavorable in general to the “mass immigration of any class of aliens.” The National Security Act of 1939 legalized ongoing practices of discrimination against the Jewish refugees. They were labelled as “enemy aliens” and subjected to regular police surveillance. Their movement was limited by harsh travel restrictions. They were also not allowed to become naturalized citizens in Australia. When evidence of Nazi genocide of the Jews came to light in 1942, the situation gradually changed. They formed the “Association for Jewish Refugees” in 1942 and bargained for a better status in Australia. Their individual and organizational efforts bore fruits. The 1939 Act was amended in 1943. They were no longer viewed as enemies and were recognised as “refugee aliens”. Due to these improvements, German Jewish refugees managed to sustain themselves financially in Australia. Soon enough, they were also given the right to become naturalized citizens in Australia. Thus, Strobl’s paper argued that the subjectivity of the Jewish refugee in Australia transformed from “enemy” to “friend” between 1937-1943. This transition in Australia was facilitated by a global recognition of Jewish plight in the face of Nazi atrocities in Germany.

In 1938, Virginia Woolf provocatively proclaimed “as a woman, I have no country”. Written at a time when the world’s population was suffering from increasing statelessness and violent displacement, Woolf sought to draw attention to the gendered nature of the ongoing political crisis. The papers by Anjali Bhardwaj Datta (Cambridge) and Rosalind Parr (Wolverhampton) attempted to do the same for the refugee crisis in mid-twentieth century India. Their papers centered the role of women within global refugee histories by investigating the Partition of India in 1947. They asked, how was refugee selfhood gendered?

Rosalind Parr’s paper illustrated that transnational discourses on universal rights were implemented by women activists and politicians in India, to shape variegated policies on refugee rehabilitation. She engaged with the debates leading up to the Abducted Persons (Recovery and Restoration) Act of 1949 in India. She evaluated the involvement of elite women, in the Indian government and in women’s organizations, in formulating refugee rehabilitation policies. Sucheta Kripalani organised the Central Relief Committee for refugee resettlement before any other attempts were made by the Indian state. Purnima Banerjee secularized the category of “citizenship” by advocating for the rights of Muslim women refugees from Pakistan to remain in India. Rameshwari Nehru, Hansa Mehta, and Mridula Sarabhai too played a decisive role in shaping women’s belonging in the nascent Indian nation state. Tying together these threads, she argued, that elite women from diverse political backgrounds participated in refugee rehabilitation and played an important role in “shaping gendered meanings of citizenship” in postcolonial India.

Datta’s paper picked up where Parr left off. She asked, how did policies of refugee rehabilitation mold the female refugee in postcolonial North India? The figure of the female refugee became fragmented along lines of class, caste, religion, and age. Rural women largely could not access any rehabilitation facilities in Delhi, due to bureaucratic and gendered limitations. Older women of lower class-caste backgrounds faced the same hurdles. However, the marital status of refugee women played a crucial role in determining their access to rehabilitation. Widowed women were rehabilitated out of concern that they might take to sex-work. The Government of India ran marriage bureaus which aimed to get single refugee women married so that they could find their place within the household. Moreover, the support provided by the Indian state to the refugees for economic empowerment remained gendered. Whilst male refugees were trained in engineering works, female refugees were encouraged to practice crafts and nourish India’s fledgling cottage industries from their homes. The female refugee was circumscribed within the space of the household by the postcolonial Indian nation state. Thus, Datta acknowledged the struggles of the refugee woman in acquiring “a room of her own” in postcolonial India.

From Syria to Myanmar, from Ukraine to Afghanistan, from India to China, the figure of the refugee continues to haunt our present times. Atrocities of state and capital displace more and more people with every passing day. Some become classified as political refugees, others as climate refugees. This condition of homelessness is pervasive in the modern age. State and capital transform all beings into “unbeings”. In this context, the enquiries of the workshop remain timely and relevant. Historical explorations of global refugee selfhood indicate that international organisations of the Global North as well as nation states failed to address the refugee crisis in the twentieth century. It required global solutions which could not be provided adequately due to conflicting national interests. This remains the central tragedy even today. For our present refugee crisis, we urgently require subalternist as well as non-anthropocentric policies which are informed by caring interdependence, rather than by exploitative extractivism – which place refugees at the heart of a politics of care, across racial, class, gender, and even species borders. How can we make our world habitable for all, once again? In this I hope we shall learn from the nonhuman, such as from the geese. As migratory birds, they do not pay heed to national borders. They do not take into account any anthropocentric notions of private property. They live and travel without paperwork. The earth becomes their own. Someday, I hope, it will be the same with humans.

Shuvatri Dasgupta is Lecturer in School of History, University of St Andrews. She is also a doctoral candidate at the Faculty of History, University of Cambridge and an editor for the Journal of History of Ideas blog.

Featured Image: Balata refugee Camp. Circa 1950, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.