By Caroline Adler and Sophia Buck

From July 7-9 2022, the international conference Walter Benjamin in the East – Networks, Conflicts and Reception [1] took place at Berlin’s Leibniz-Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung (ZfL). It examined readings, receptions, and appropriations of the work of German Jewish philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin in Central and Eastern Europe, during and after state socialism. The title of the conference, Walter Benjamin in the East, refers first of all to a Western European orientation towards the East in the 1920s. Benjamin himself traveled to the ‘margins’ of Europe (as they were then seen from a Western perspective) during his trip to Moscow in the winter of 1926/27.

Benjamin’s preoccupation with the young Soviet Union – poignantly laid out in his essay Moscow for the journal Die Kreatur and numerous essays on cultural politics in Die Literarische Welt – is an outstanding example of his ability to think “off-modern” and to “detour into the unexplored potentials of the modern project”. Indeed, Benjamin observed the USSR in its formative years with an eye toward what Svetlana Boym called the clash of two ‘eccentric’ modernities, evident in the tensions between a utopian, revolutionary potential and the restorative, soon-to-be totalitarian tendencies of the late 1920s. This preoccupation, in turn, remains a marginal aspect in Benjamin studies, at least when considering most scholarship conducted at and circulating in ‘Western’ academic circles.

The clash of these two contingent – temporally and spatially ‘out of sync’ – modernities is said to have ended with the collapse of the so-called Eastern Bloc between 1989 and 1991. A subsequent hope was that largely separate communities of scholars were to create a newly interwoven intellectual landscape in Europe. First, by creating and fostering intellectual networks and mutual academic exchange. Second, by retrospectively acknowledging the intricate and mutual cross-connections during a long 20th-century divide between Western and Eastern versions of modernity, as embodied in Walter Benjamin’s tumultuous reception.

Taking up this undertaking, scholars, translators, and editors came together in Berlin to present and discuss different case studies on the reception and productive appropriation of Walter Benjamin’s work: in 1920s Moscow, the GDR, the Socialist Republic of Romania, the Hungarian People’s Republic, the CSSR, as well as contemporary Romania, Ukraine, Poland, Russia, and Slovakia.

The conference started with the chronological ‘origin’ of Benjamin in the East – his travel to the young Soviet Union in 1926/27, alongside his reception of and work on Soviet aesthetics and literary practice. Pavel Arsenev (University of Geneva) introduced Benjamin’s preoccupation with the works of the Soviet literary avant-garde – namely Sergei Tretiakov – as a form of ‘reverse thinking’, interpreting Benjamin as an intermediary of the Soviet avant-garde in Western Europe, especially Paris. While these contacts between ‘the East’ and ‘the West’ were mainly reduced to issues of technology and production, Arsenev highlighted contact points to the social sciences, in particular ethnology and anthropology.

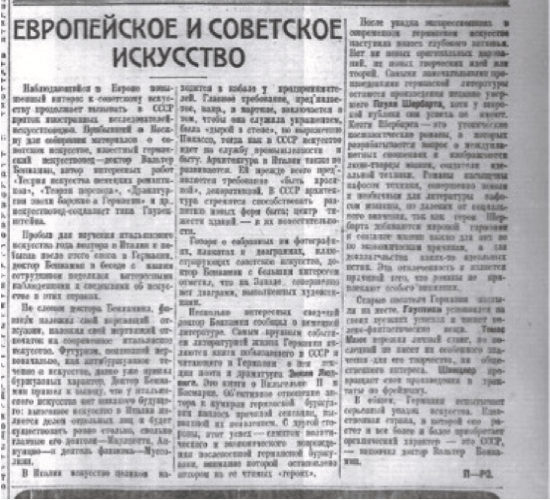

Moments of contact and synergies ‘against the grain’ were also of interest to Iacopo Chiaravalli (University of Pisa), who presented an exciting archival find: the issue of the Moscow newspaper Vecherniaia Moskva that includes an interview on “European and Soviet Art” that Benjamin gave in 1927. This interview, in Chiaravalli’s interpretation, served Benjamin as the starting point for his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), tracing back Benjamin’s thoughts on the aestheticization of politics to discussions with Bernhard Reich and Asja Lacis in Moscow. While Benjamin remarked signs of a growing orthodoxy and dogmatism of Russian cultural production, he did not revert to bourgeois aesthetics but radicalized his concepts of technology and the materiality of social production.

Our conversation on ‘re’-constructing the 1920s continued with Sergei Romashko’s (Moscow) keynote “Walter Benjamin/Moskau – Zwei Flächen eines Kristalls” [Two planes of a crystal]. Romashko – himself the Russian translator of Benjamin’s Moscow Diary – focused on some speculative possibilities of encounters between Benjamin and figures such as Iakov Slashchov, Michail Bulgakov, Lev Kuleshov and Viktor Shklovski. Through reading Benjamin’s Diary as a historical, yet unfinished sourcebook, Romashko offered a timely understanding of Benjamin as a ‘conversation partner’ in reconstructing a history buried by the ruptures of fascism and Stalinist repression.

A joint visit to the Walter Benjamin Archive rounded up the first day, guided by the archive’s research associate Ursula Marx. In addition to the rare opportunity to marvel at Benjamin’s original manuscript of the micrological Moscow Diary, there was a lively discussion about practices of archiving and cataloguing non-German editions and translations. While the opening and accessibility of the archive, on the one hand, promotes the study of Benjamin, on the other, it makes ‘quality management’ more difficult, as keeping track of new translations, editions or appropriations of his work is a task on its own.

On the second day, the section on Theoretical Reception until the 1990s targeted productive appropriations [‘Entwendungen’] of Benjamin’s work in the GDR, the Hungarian People’s Republic, and the CSSR. Martin Küpper (FU Berlin) discussed how Benjamin’s reflections on operative aesthetics and reproduction techniques were incorporated into the philosophical canon of the GDR after 1968. Of central importance were figures like Lothar Kühne, whose reception of ‘aura’ and concepts of ornament and ‘Behutsamkeit’ [gentleness; caution] considerably touched on functional aesthetics as an approximation of situation and space. Adapting and reworking Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’, Kühne challenged the schism between utility and handicraft while criticizing commodity fetishism.

Konstantin Baehrens (University of Potsdam) focused on an important mediator of Walter Benjamin’s work in the socialist context: György Lukács. Lukács stimulated a reading of Benjamin not only among members of the Budapest School but also in the environment of the Yugoslav Praxis Group and Marxist philosophers in the GDR – a redirected interest in modernist tendencies of the 1920s, at a time when Lukács himself was ostracized from official cultural politics. Both Baehrens and Küpper amplified the role that reception plays in legitimizing ideological standpoints. Thereby, the papers provided striking examples of the practical use of Benjamin’s theoretical legacy beyond a philological ‘Benjamin-School’.

Gábor Gángo (University of Erfurt) further expanded the engagement with the Budapest School. For him, too, the reception and appropriation of Benjamin’s work, especially through Hungarian writer Sándor Radnóti, can be understood as a kind of ‘mediation’ or reconciliation between Eastern and Western versions of modernity and its respective strains of Marxism. Following the reading of Benjamin through Lukács, Anna Zséller and Károly Tóth (ELTE) presented excerpts of extensive interviews they had conducted with editors and translators of Benjamin’s work in Hungary. These conversations with figures such as Radnóti, Mihály Vajda, or János Weiss gave striking insights into a ‘Marxist Renaissance’ in Hungary up until the 1970s and its sudden halt after the so-called ‘Philosopher’s Trial’ in 1973. These circumstances produced a unique ‘belatedness’ in the publication of Benjamin’s work in Hungary and a reception marked by fragmentation and generational conflict.

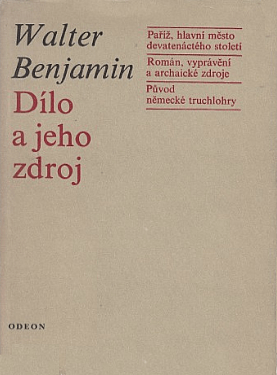

Concluding the section, Anna Förster (University of Erfurt) focused on the intellectual climate and conditions for a Benjamin reception in the CSSR after 1968. Her contribution centered on the 1979 Czech edition Walter Benjamin: Dílo a jeho zdroj and how – unlike other Western philosopher’s works – it was possible to get it past the multiple censorship laws, despite Benjamin being considered a ‘horkým bramborem’ [touchy subject]. Förster examined the tactics of editors and translators to escape censorship not through anonymity or pseudonymity but through allonymity: a practice whereby authors and translators ‘lent their names’ to colleagues who could not publish officially.

The section Artistic Responses until the 1990s engaged with artists’ responses to Benjamin’s work in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Due to its split with Stalin after 1948, Yugoslavia went a quite distinct path, resulting in its transitioning towards market-based socialism and relatively liberal cultural politics. Isabel Jacobs (Queen Mary University of London) focused on the underground art practice of Goran Đorđević, his disappearance and subsequent resurrection as ‘Walter Benjamin’ in a 1986 performance lecture in Ljubljana. Jacobs proposed to consider Đorđević’s artistic strategies of copying and un-originality less an ‘influence’ of Walter Benjamin than a reversed intervention that questions claims of cultural originality.

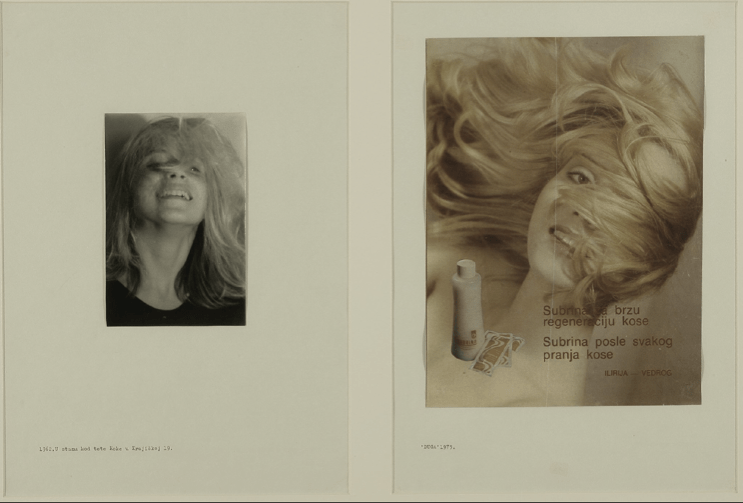

Deirdre Smith (University of Pittsburgh) took a closer look at artists of the New Art Practice Movement in 1970s Yugoslavia, particularly the work of Sanja Iveković. Smith pointed out that Iveković’s artistic strategy of montage and image-constellation can be traced back to a specifically feminist reading of Benjamin’s work in the edition Eseji, published in Belgrade in 1974. Both contributions referred to the productive possibilities of a non-academic, but rather interventionist appropriation of Walter Benjamin’s work in a relatively liberal socialist context.

The section Artistic Responses since the 1990s targeted cultural, theatrical, and cinematic as well as film-theoretical engagement with Benjamin’s work in contemporary Russia and Romania. In her keynote “Translating Benjamin from Theory to Practice – Russian Edition”, Oxana Timofeeva (St. Petersburg) evoked some of Benjamin’s concepts – such as the angel of history, divine violence, and the tradition of the oppressed – and their harnessing within political struggles in today’s Russia.

Timofeeva recalled the artists collective Chto Delat‘s 2014 performance “Who burned a paper soldier,” in which the collective transformed the vandalization of an installation in public space into an investigation of monumentality in collective memory culture. In doing so, the self-incrimination of the Angel of History aimed at exploring emancipatory strategies for addressing and overcoming entangled complicities in the past. The urgent task of demystifying Benjamin, Timofeeva suggested, begins with exposing him as a dislodged reference material or ‘cultural asset’. Instead, a militant reception in the art world would allow to grasp an ‘untimely’ moment in his philosophy through our own experiences and struggles.

In a similar vein, Bogdan Popa (Transilvania University Romania) explored how the reception of Benjamin transited from branding him as a historical materialist thinker to a reference for ‘cultural studies’ within Romanian film theory. The influence of Benjamin on Romanian film theory and aesthetics are surely productive. However, Popa argues, Benjamin’s thought needs to be decisively situated in a Marxist tradition of thinking; also to be able to reconceptualize Romania’s own history of socialism. Here, the works of Benjamin are seen not through the lens of appropriation but through the possibility of theoretical self-understanding.

In contrast, Anna Migliorini (University of Florence and Pisa) examined the productive appropriation of Benjamin in the aesthetic realist school of Romanian New Wave cinema, in particular the movies of Radu Jude. In her analysis of Radu’s work, Migliorini pointed out two purposes of such an appropriation: on the one hand, as a thematic reference and, on the other, as a methodological model.

The last section on Day 3 dealt with theoretical landscapes and Reception since the 1990s, specifically Romania and Slovakia. Markus Bauer (Berlin) traced the political, linguistic, and social-theoretical preconditions of Benjamin’s reception in Romania from 1972. He outlined various theoretical influences of Benjamin’s work that conditioned the respective reception waves in Romania, as enacted through, for example, Valeriu Marcu, René Fülöp-Miller, or Panait Istrati. At the center of the subsequent discussion was the concept of ‘Europe’, both in Benjamin’s writing, but also in the self-understanding of the Romanian reception marked by the discovery of Benjamin’s works in French translation.

Adam Bžoch (University of Bratislava) brought together areas of artistic engagement and theoretical reception in Slovakia as ‘traces of an apparition’ assembled in a 2006 conference ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Media Challenges’ in Bratislava and an accompanying exhibition in 2008. The 1990s saw a shift toward Benjamin’s art and media theory. For example, the translation Iluminácie (1999) – only coinciding with the German edition by chance – was curated along the lines of media-theoretical considerations rather than literary reflections.

Following from the ‘Velvet Divorce’ (or dissolution) of Czechoslovakia in 1993, Slovak intellectuals also increasingly tended to foreground biographical aspects of Benjamin’s exile as a starting point to rework a perceived disconnection from Slovakia’s own history. Both Bauer and Bžoch highlighted the importance to address social and political contexts of particular receptions, as new editions and translations also constellate novel proximities of thought that can change supposedly ‘neutral’ readings radically.

The final roundtable discussion Translating (in) the East took up these questions once again and expanded the spectrum towards the possibility to intervene through translations and editions. Three translators and editors reflected on their practice, considering circulation, institutional infrastructures, publication requirements, discursive tendencies, and readership. Kateryna Mishchenko (Berlin) started to work on translations of Benjamin’s writings on dreams in 2014 to introduce them “as an alternative form of political reflection”.

More translations into Ukrainian gradually appeared after the turn of the century, with a focus on political aspects and echoes in artistic circles. In light of the war in Ukraine, Mishchenko advocates further Ukrainian translations not as an alternative to existing Russian ones but to open a linguistic zone for pondering ambivalences, tensions, and mutual illuminations. Whilst translations culturally transform Benjamin’s thought, they are also a means for a translator to construct a future for transcultural and political community building.

Christian Ferencz-Flatz (Alexandru Dragomir Institute for Philosophy Bucharest) – currently working on translating Benjamin’s Arcades-Project into Romanian – outlined the recent translation history within the Romanian intellectual landscape. First comprehensively translated after the fall of the socialist regime, Benjamin would become part and parcel of ‘culture wars’. Iluminări (2000), translated by Catrinel Pleșu, favored a depoliticized, theological selection that supported an anticommunist stance. Nonetheless, Benjamin’s writings soon turned into a key piece of ammunition in constituting a New Left shortly before Romania’s integration into the EU. Ferencz-Flatz inscribed Benjamin’s work into a consistent streak of new translations since, accompanied by a more thorough academic engagement with Benjamin’s writings.

Adam Lipszyc (Polish Academy of Sciences Warsaw) situated his own Polish translation against the horizon of historically longer trends and re-translations in Polish academia. Broadly, the reception of Benjamin passed from aesthetics and literary theory (1970s) through cultural studies (1980/90s) and post-secular readings down to a political philosophy across the political spectrum. Similar to Ferentz-Flatz’ observation for some Romanian translations, more politically ‘conservative’ or ‘leftist’ presentations of Benjamin would take shape through curating his Œuvre selectively according to ‘theological’ or ‘Marxist’ underpinnings. Lipszyc’s translation, in his view, aimed at reinstating the philosophical value of Benjamin’s work as opposed to a restricted view of him as either a theologian or a media theorist.

The conference brought together perspectives from the European ‘East’ in a fascinating and fruitful constellation. Thereby, it opened outlooks for future collective work on the entangled aspects of Western, Central and Eastern European intellectual histories through the lens of Benjamin’s legacy. Understanding the afterlife of his thought as it traverses ideological and geographical boundaries also means accounting for the specificity of local contexts. Individual case studies from this conference highlighted previously neglected similarities as well as differences within the European context.

Going beyond essentializing a ‘Polish’ or ‘Romanian’ or ‘Hungarian’ version of Benjamin, the contributions shed light on how reception and translation may enable scholars to reinterpret and expand Benjamin studies across linguistic contact zones. With this outlook, real and imaginary constructions of the ‘East’ and ‘West’, for instance when speaking about divides within Marxism, were critically addressed. Thus, the conference unveiled how a focus on the various receptions and appropriations of Walter Benjamin’s work across Europe may open up a new, transnational home for a supposedly ‘over-researched’ thinker.

[1] The event was supported by the ZfL Berlin, the Oxford/Berlin Research Partnership, and the Research Training Group GRK 1956 “Transfer of Culture and Cultural Identity” in Freiburg.

Caroline Adler is a scholar of Cultural History and Theory. Her research focuses on representation, method, and literarization in Walter Benjamin’s work, epistemologies of the aesthetic, and theory and critique of scientific exhibition practice. She is a PhD Student in the Research Training Group The Literary and Epistemic History of Small Forms at Humboldt-University Berlin, where she works on Benjamin’s “Moscow” essay between vividness and literary construction. She is an active member and treasurer of the collective diffrakt – centre for theoretical periphery in Berlin-Schöneberg.

Sophia Buck is a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford in German Studies and an associate of the Research Training Group Transfer of Culture and “Cultural Identity”. German-Russian Contacts in the European Context in Freiburg. Her research concerns literary criticism and theory, European cultural thought, intercultural optics, knowledge transfer, and the history of the discipline. She currently writes a doctoral thesis with the working title “Moscow – Berlin – Paris: Walter Benjamin’s Transnational Spaces of Comparison”. In 2021, she was a visiting researcher at the École normale supérieure Paris, and until summer 2022 a visiting researcher at the Leibniz-Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung Berlin.

Edited by Isa Jacobs

Featured Image: Book Cover of Walter Benjamin’s Moskovskii dnevnik [Moskauer Tagebuch], Moscow 1997. Credits: Ad Marginem.