By Ankur Barua

Today, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam are often presented as three rigidly self-enclosed worldviews in political rhetoric and historical reconstructions of the last two millennia in South Asia. This think piece reveals a different picture by navigating theological exchanges across the social spaces of Hindus and Muslims, focusing on the idioms and the affectivities of devotional love (taṣawwuf, bhakti). We begin with an outline of the religious history of South Asia, highlighting how the arrival of a non-Indic religion – namely, Islam – led to various political upheavals and the development of interfaces of mutual intelligibility. The Hindu scriptural text, Bhāgavata-purāṇa (c.1000 CE), became the generative matrix of certain Indo-Islamic styles of devotional poetry which writers cultivated from both Hindu and Muslim backgrounds. The central motif — Kṛṣṇa (Krishna), the God of enchanting beauty, and the gopīs, the cowherd women who are the prototypical devotees – would be reworked multiple times across the precolonial centuries and in contexts of colonial modernity.

During the first century CE, two spiritual visions – today clustered under the rubrics of “Hinduism” and “Buddhism” – gradually developed their conceptual contours, occasionally in dialectical competition with each other’s idioms. They spoke in the common Sanskrit-rooted vocabulary of ātman (self), saṃsāra (cycle of rebirths), karma (action), avidyā (ignorance), and jñāna (knowledge), even if they occasionally disagreed sharply on how these crucial terms should be understood. Hindu and Buddhist (“Indic”) philosophers were developing sophisticated analyses of a range of motifs: the nature of reality, the structure of cognition, the shape of the ideal polity, and soteriological discipline, to name a few. The knowledge these philosophers cultivated often depended on the patronage of local kings and powerful landlords. For instance, brahmin priests were not averse to ritually consecrating a ruler through singing Vedic chants in return for tax-free lands on which to build temples and found monasteries. These sites would become the Hindu homes for propounding – and sheltering – the dharma.

The polyvalent word dharma – like the Greek word logos and the Arabic word dīn – defies translation. From a cosmic perspective, dharma is the cement of the universe: the sky is not falling on my head right now because the sky has a specific dharma-grained structure. From a socio-moral perspective, dharma is the existential engine animating everything related to what I think, where I live, and how I act. Around the turn of the first millennium, the motif of dharma was codified by Sanskrit-speaking brahmins who prescribed specific duties for women (strī-dharma) and for individuals belonging to specific groupings (varṇa) with their distinct occupations. These socio-ritual classifications are encompassed in the dharma-sāśtra literature (200–700 CE), which was subsequently reworked by the different Vedantic traditions. Crucially, the dharma-sāśtra codifications pointed to the lands of the “outsiders” (mlechha, yavana) where the cosmos-regenerating dharma could not be practiced.

A few centuries later, Islam irrupted into Indic lands. In one sense, this generalization is as misleading as the claim “Hinduism landed at Heathrow in 1972”. People move, and they move along with their ideas housed in their sociocultural systems. Likewise, we should speak of a diverse spectrum of intellectuals, traders, and settlers who began to stream eastward from lands as far away as Iran, Turkey, and Afghanistan. These movements were initiated by a series of devastating raids on lands and Hindu temples – hence, the image of an irruption – carried out by Muslim figures such as Mahmud of Ghazni (971–1030) on the north-western terrains of India. In 1206, a Sultanate was established at Delhi by a Persianate dynasty; much of the landmass of South Asia was controlled by Indo-Turkic and Indo-Afghan kings before Mughal paramountcy was founded in 1526.

Picture Delhi in 1622. The “inter-faith” landscape does not look particularly promising. To many of the Hindus we meet in the local temple, Islam is stamped with alienness – the (Persian and Mongol) rulers and courtiers are ethnically distinct, they speak weird languages, and their stand-offish mleccha-lifestyle does not conform to the dictates of dharma. First impressions often matter more than any high-minded idea you throw at others – the apocalyptic nightmare of ruthless hordes raining down hell on infidels structure the “imaginaire” of these Hindus. But perceptive (ethnographic) eyes would discern something more, especially in the vast hinterlands beyond the contact zones ravaged by military mobilization: Islam is becoming indigenized in music, painting, medicine, and dress. Urdu appears at the intersections of Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit linguistic streams; Muslims are translating Hindu scriptural texts such as the Mahābhārata, the Rāmāyaṇa, and the Yoga–vaśiṣṭha into Persian; and certain styles of architecture combine Islamic and Indic forms.

One such “inter-faith” pioneer was the Mughal prince Dārā Shukōh (1615–1659), who was born at Ajmer, the city with the tomb (dargāh) of the Sufi master Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti. Heeding a call from the minaret, Shukōh felt inspired to boldly declare that explanations of the Qur’ān could be found in the Sanskrit Upaniṣads. A recurring Islamic critique of Hindu religious life-worlds was founded upon the latter’s polytheism; however, while Dārā was plumbing the depths of Islamic unicity (tawḥīd), he discovered Indic pearls such as this declaration from the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (6.2.1–6.2.3): “In the beginning, this was simply what is existent–one only (ekam eva), without a second”. A generation before Dārā, Ras Khān (Syed Ibrahim Khān: 1548–1628) had walked down another pathway that would become a vitally osmotic site of synthetic borrowings across Hindu-Sanskritic and Muslim-Perso-Arabic milieus – the language of self-effacing love (prem, bhakti, ‘ishq, maḥabba). While little is known about his life, it is clear from his couplets (doha) that he was immersed in Hindu theological universes, and especially fluent in speaking the idioms of ecstatic love of Kṛṣṇa as expressed in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa by the exemplary cowherd women.

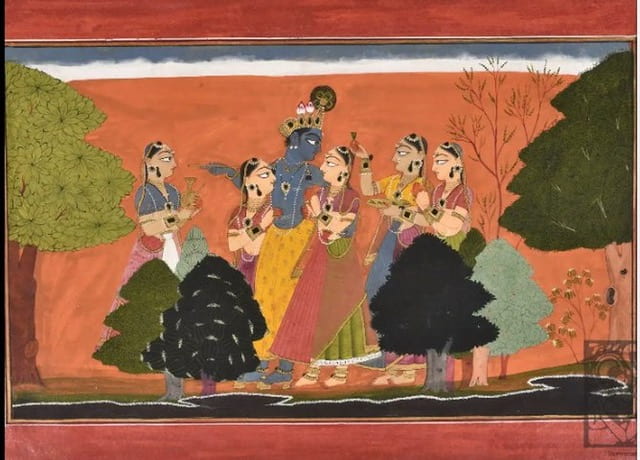

In a cosmic narrative that would be engraved into multiple styles of painting, poetry, architecture – and later Bollywood music – the Hindu God Kṛṣṇa plays on his world-enchanting flute whose mesmerising call is heard by his ideal devotees, the cowherd women (gopī). Leaving aside their strī-dharma in response to this call of the spirit, the gopīs rush to meet Kṛṣṇa. The scriptural narrative now unfolds through a series of dialectical twists and turns – the gopīs become inflated with pride and think that they possess Kṛṣṇa, suddenly Kṛṣṇa disappears, they are riven with an unbearable pain of separation, and finally, Kṛṣṇa re-appears and dances with them in a circular formation. Reflecting on the pathos experienced by them in separation from Kṛṣṇa, Ras Khān writes that when a gopī hears the melodious call of the cuckoo in the springtime, she feels excruciating pain.

An entire army of Hindu exegetes began to work on this (historical-mythic) narrative. How did they explicate it? The Kṛṣṇa-gopī dance represents the spiraling oscillation between the non-finite divine self and the finite human self. God wishes to draw us ever more tightly into the divine matrix, but we are not yet ready for God–marred as we are with our worldly imperfections. So, God entangles us with the lure of love (bhakti) and keeps on – time and again – turning us away from our worldliness till our hearts become perfectly Godward. In loving this world – God’s world – we must inhabit it by unswervingly turning our heart’s compass towards God. At the spiritual summit, a Hindu devotee would declare: “God: everything I do – including submitting this confession to you – is an expression of my bhakti for you”. In short, love is (not just a candlelit dinner but also) a fiery crucible that burns away our existential dross so that we become increasingly worthy of the God who would (deign to) dance with us. Love hurts, and in that agony is salvation.

All these themes are encoded in līlā – a Sanskrit word whose semantic range cannot be encompassed by one English word. Distracted by the demands of the next publication, I routinely fail to discern any divine presence in the dusty shelves of libraries. Then, God shocks me out of my existential complacency, and fills me with unbearable pain as I experience God’s absence. Paradoxically, when I feel, with my gopī-self, that God has deserted me, I become wholeheartedly re-oriented to God. So, God freely chooses to draw me outwards on a journey of deepening love of God as part of God’s līlā.

Depending on your academic affiliations (and existential dispositions), all this may be too much “theologizing” for you. However, no theological system can survive for too long if it is completely disconnected from the heat and dust of everyday life – and indeed, quotidian analogues of these cosmological claims can be found. That you experience presence in absence is a platitude to which the wisdom of Bollywood repeatedly points you (such as this song: “Why does it happen in life – when you have left, it is just then that I suddenly remember all these little things about you?”), and every divorce lawyer will caution you that taking your spouse for granted is a recipe for existential disaster.

Figures such as Ras Khān recognized that this bhakti-shaped vision was more than malleable for Sufi (in Islamic terms, taṣawwuf) hermeneutic recalibration. The Sufi motifs of the painful surgery (fanāʾ) of the world-immersed self, the (symbolic) exile (hijrat) from the divine who is our true home, and the practice of constantly re-calling (ḏhikr) the (ninety-nine) names of our gracious host were housed across the hinterlands of Hindustan by reimagining Hindu hymns. The utterly destitute (Arabic: faqīr; Sanskrit: akiñcan) devotee still abides in (and because of) the divine plenitude. Again, in the Sufi cosmologies of Mir Sayyid Manjhan’s Madhumālatī (1545), love (Sanskrit: prema) is presented as the cosmic glue through which the tissues of the “unity of being” (waḥdat al-wujūd) are threaded together. The narrative is set as a circle of love within which Manohar meets the heroine Madhumālatī at night, gets separated, and painfully works his way back to her through various halting places. Manohar and Madhumālatī become the relishers of the sentiment (Sanskrit: rasa) of prema, such that the wayfarer (sālik) is the lover (‘āshiq) who sees in their love for the human beloved (‘ishq-i majāzī) a reflection of their love for the divine beloved (‘ishq-i ḥaqīqī). Around this time, Mīr Abdul Wāhid Bilgrāmī (d.1569) suggested, in his Haqā’iq-i Hindī, allegorical readings of Kṛṣṇa as the reality of a human being, the cowherd women (gopīs) as angels, and the flute of Kṛṣṇa as the appearance of being out of non-being.

In short, both these worldviews, of taṣawwuf and bhakti, are shaped by the allegory of love – what applies to the human beloved is a this-worldly instantiation of what is paradigmatically exemplified by the divine beloved. So, statements about a human lover are translatable – with some disanalogies – into statements about the divine lover. Thus, propelled by the call to return to God, the Sufi wayfarer wanders about, bewildered and yet assiduously, on the paths of love – paths that lead through the battlefields of Karbala, the rose gardens of Shiraz, and the hermitages and the marketplaces of India.

These syntheses of bhakti and taṣawwuf spread across Indic terrains, and by the eighteenth century, many Muslim poets were singing of Kṛṣṇa. In a middle Bengali reworking of the narrative Majnūn Laylā, Daulat Uzir Bahrām Khān (c.1600 CE) infuses the Perso-Arabic idioms of “veiling”, confusion, and selfless love (maḥabba) with the vernacular valences of painful separation (biraha).

[Lāylī says:]

The fire in my mind burns without respite

Strength, intellect, happiness, purity – all have I lost

In solitariness do I stay enclosed in biraha.

In this way the grieving woman-in-separation (birahiṇī) suffers always As she lies close to death.

My translation from A. Sharif, Lāylī-Majnu (Dhaka: Bangla Academy, 1984), p. 129.

Sometime before the eighteenth century, we hear the lament of another Muslim poet as he sings of Kṛṣṇa (not named but hinted at with stock allusions).

Without my friend –

I waste away day and night

I cannot restrain myself.

Tell me, my girl-friend, what do I do now?

Without my friend my life has no companion,

I keep on waiting every day for my friend.

In that waiting I go about floating on sorrow,

If I were to find my friend, I would hold on to his feet.

Irfān says –

“My friend is the flute player, By playing on that enchanting flute he stole my heart away.”

My translation from J. M. Bhattacharya, Bāṅgālār Baiṣṇab-Bhābāpanna Musalmān Kabi (“Bengal’s Muslim Poets Infused With Vaiṣṇava Sentiments”) (Calcutta: Calcutta University, 1945), p. 48.

In such premodern songs, it is only in the line where the author signs their name that the author is revealed as an individual from a Muslim milieu who is lamenting their sorrow in separation – or exile – from their friend who is the divine beloved. This stream of sonic theology – Hindu and Indo-Islamic – continues to flow through the lands of Bengal (in India and Bangladesh). Here is a fragment of such a song from one of Bengal’s finest poets, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).

The night that is passing, how do I bring it back?

Why do my eyes shed tears in vain?

My translation from R. Tagore, Gītabitān (Calcutta: Visvabharati, 1938), p. 370.

Take this dress, my girl-friend, this garland has become a burden—

Waiting in desolation on my bed, a night such as this has passed.

Such allegorical reworkings of the narratives of Kṛṣṇa and the cowherd women appear also in the poems of Hason Raja (1854–1922). Born in Sylhet (present-day Bangladesh), he invokes various Hindu tropes in presenting himself as a girl whose heart has been captivated by Kṛṣṇa. Thus, (s)he pines away, by “annihilating” (fanā) her worldly self in her love for the divine beloved.

I shall let the national poet of Bangladesh, the inimitable Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899–1976), have the last word. He inherited some of the theological idioms configured by figures such as Ras Khān, and his socioreligious visions do not allow any straightforwardly modular characterisation as either “Hindu” or “Muslim”. For instance, he composed songs about both the Prophet Muhammad and the Hindu goddess (debī). Married to a Hindu woman, fired by a cosmic vision of Islam as the gospel of egalitarianism unto the wretched of the earth, and tragically reviled – both by Muslims and by Hindus – precisely because of his hybrid socioreligious locations, Nazrul skilfully interweaves the threads of bhakti into the tapestry of taṣawwuf.

O girl-friend, in your youth dress up as a yogi

Go looking for Kṛṣṇa in forest after forest

Hearing his flute, abandon all concerns about family honour

Kalyani Kazi (ed.), K̭āzī Nazruler Gān (Calcutta: Sahitya Bharati Publications, 2005), p.602.

Keep searching for him along the pathways

The “de-familiarization” that bhakti points to – this world is our home and yet it is not quite our true habitat – would become the generative motor of the migration of Hindu devotionalism (for instance, ISKCON, a Hindu organisation founded in 1966 in New York by Swami Prabhupāda and the Neasden Temple in London) across national borderlines. In the reverse direction, the motif of bhakti provided the conceptual currency to Muslims in their multiple quests to modulate the Meccan message to Indic idioms, as they went looking for rejuvenating oases for Islam across the heartless deserts of the world.

Ankur Barua is a senior lecturer at the University of Cambridge. His primary research interests are Vedantic Hindu philosophical theology and Indo-Islamic styles of sociality. He researches the conceptual constellations and the social structures of the Hindu traditions, both in premodern contexts in South Asia and in colonial milieus where multiple ideas of Hindu identity were configured along transnational circuits between India, Britain, France, Germany, and USA.

Edited by Luke Wilkinson

Featured Image: Krishna with Gopis (Creative Commons).