By Alexander Collin

Shoufu Yin is an assistant professor in history at the University of British Columbia. His research centers on Chinese and Inner Asian political cultures and thoughts in global historical contexts.

Yin spoke with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article, “Redefining Reciprocity: Appointment Edicts and Political Thought in Medieval China,” which appears in volume 83, issue 4.

***

Alexander Collin: Let’s start with some general background. Your research is very broad; you’ve written on periods from the eleventh to the seventeenth centuries, not only covering China itself, but also its global connections with Koreans and with Europeans and even the history of animals. Could you start by setting your recent JHI article in a little bit of context? How did you come to write about Tang Dynasty edicts and how do they fit into your work more broadly?

Shoufu Yin: Yeah, this article addresses an even earlier period, right? It is about Tang China, and especially about ninth-century transformations. The article is a sort of nexus of different things I have been doing. It is about rethinking or even rewriting intellectual histories by focusing on the functional, bureaucratic documents, such as the edicts received from the emperor or the petitions that would have been sent out. We might think that these documents are tedious, repetitive, formulaic, and rote; however, I really think they are as rich in political thought as the treatises, chronicles, and other genres familiar to intellectual historians. In order to read these formulaic documents as sources for the history of ideas, it is imperative to understand their tradition as genres, as objects, and as a part of the institutional processing. The Tang laid out a model, which is important for East Asia in later centuries. This is why I take a longue durée approach to history.

Interestingly, the use of these official, functional documents often happens in transcultural, trans-polity contexts. It is not only diplomatic documents that matter. It is also about people going to other realms and courts, submitting a document while following local rules. For example, I am originally from Shanghai, but when I came to Canada, I needed to write visa applications and grant proposals that aligned with Canadian standards. The process of filling in blanks in these bureaucratic forms is itself a transcultural and translingual practice. Likewise, when the Jesuits or the Koreans arrived in China, they needed to draft petitions: “Hi, we lack this or that; we are starving. Please give us something.” How do you do that? You need to learn to write these official documents, to express your concerns and make a petition in this unfamiliar and idiosyncratic context. This is another dimension that links my projects together. They are about how individuals—in many cases non-elite individuals—utilized these documentary technologies and forms in different contexts to advance their concerns.

AC: I’d like to follow up with another contextual question, this time a little more specific to the article. You introduce two concepts in the piece: the commoner-centered approach to appointments and the official-centered approach to appointments. I would like to ask you about your influences there, either other historians or philosophically. What’s the background to these terms you introduce here, and what led you to that insight?

SY: Maybe I should provide a bit more background here. There’s a kind of clichéd or stereotypical vision that the history of political thought of imperial China is about benevolence and meritocracy. Accordingly, the emperor was responsible for taking care of the subjects, and for this reason, they employed worthy officials to promote the common good. Something like that. Even in recent debates, some scholars have imagined that this kind of benevolent meritocracy provides an alternative to liberal democracy. To be very frank, I’m so sick of that kind of argumentation. At a philosophical level it doesn’t make sense, at least not to me. Critically, from a historical perspective, I think it misrepresents a lot of documents, and it is based on a very selective reading of the sources from the Chinese and East Asian traditions. So, big picture number one is that, if we go beyond a specific and very confined scope of sources, and pay real attention to the kinds of documents with which political actors do things, we will discover that this benevolent rule—what I call a commoner-centered approach, or selecting good officials for the well-being of the commoners—is only one of the multiple models of governance. There are other models that matter.

This leads to another deep concern, or big picture number two. Comparison is an important dimension. The paper has really accompanied me for nine years. During this process, I took courses from European medievalists and also Byzantinists, especially Geoffrey Koziol, Maureen Miller, and Maria Mavroudi at Berkeley. One thing that struck me was that the making of the narrative of the European history of political culture and thought has paid a lot of attention to diplomas and charters, not only the Magna Carta kind of canonical documents but also everyday documents, especially Koziol’s study. If we really want to compare China with elsewhere, we cannot start the comparison from a very limited view of Chinese materials and compare them to a research result drawn from different materials, right?

This paper, of course, is not a comparative project per se, but the first step is to broaden the source base and then to compare the right genre with the right genre, official documents with official documents, and top-down documents with top-down documents. At that point, we may realize that certain stereotypical visions of the East versus West, or China versus Western Europe, kind of boil down and we need to rethink these questions.

AC: Great. Thank you. That connects nicely to what I was going to ask you next, which is about the sources themselves, about these edicts. In the article, you describe the process by which they are created: moving from an initial drafter, then going to the chancery to be checked, and then to be made in the correct materials and so on, and then eventually to the key final officials to be confirmed and signed off. Could you talk a little more about that process and how it links to the content of the sources? Who’s having what influence in that process? And how do these things come together?

SY: Thank you, first of all, for reading that so closely. The process is a complicated one. In a certain sense, it is a black box. There are many details that we do not know, and what we do know are exceptional cases. Such exceptional cases include the edict draft being presented and then someone saying, “No, you must fix this.” And then the edict drafter says, “Oh, you are not fine with me? You do not think I’m capable of doing this? I resign.” This is one kind of exceptional case, attesting to a broader culture in the sense that the edict drafter occupies a really prestigious post and they are expected to do it well first time around.

Another exceptional case that I discuss is that, when the recipient discerns something is not right, they write a memorial saying, “Hi, I received this edict and there’s something here. . . Hmmm. . .” While this did not happen very often, it does tell us something valuable. On the one hand, the edict is really important as a cherished, cult object, so it would be put in a certain place for ancestral worship. People carry out specific performative uses of these edicts down the generations, with descendants using them as material tokens to show that their ancestors were really great officials. On the other hand, due to specific reasons embedded in the political or military situations of certain periods, the space for negotiation was more open. This was especially the case when the court really wanted to gain the support of certain groups of prefects, power holders, or local magnates. These situations opened the textual representation for negotiation.

So, the simple answer is that it’s a black box that we try our best to understand. But, there are serious limitations. Transmission is also an important problem because ultimately the edicts come to us, most of them, from literary collections. We do not know whether certain modifications were made when they were anthologized. For instance, during the eleventh century, many of them were block printed. Then, the next question is how the print culture affected the content. So with regard to that, we do the best we can, but there are still serious limitations concerning what we know about the process.

AC: Now, I’d like to come back to this cliché of benevolent rule that you were discussing earlier. In one of the sources you quote in the article, they write that “without oversight, who can say that the area will recover?” I was very interested in what sort of oversight is expected, what are the officials supposed to do? As you say, there’s a lot of normative language about how they’re supposed to take care of the area they’re appointed to in some way, but relatively few concrete directives. So, I wondered if you had more insights into what they were doing on the ground to meet those expectations?

SY: A first important argument, and one that I would make very explicit, is that previous scholars tend to read them as a kind of merely formulaic language, piling up one formula after another. So, I’m trying to show that it’s not just a random kind of compilation of formulaic language. It’s not just clichés piled up. They actually follow the argumentative structure for specific reasons. On top of that, there’s a dimension that I have not really unpacked in the article, in part due to the word limit, but also because it’s complicated and requires more exploration. There is a specific science, a Wissenschaft, a system of knowledge already systemized in the third century, which concerns personnel management based on an ontology and epistemology of human talents.

By the seventh and eighth centuries, we are talking about a very well-established field of knowledge in imperial China. Basically, the idea is that everyone has their own strengths and weaknesses. Today, we probably believe that if we really work hard, we might eventually overcome our weaknesses. The elites of Tang China believed, however, that one can hardly get rid of one’s weaknesses because strengths and weaknesses are two sides of the same coin. Or at least in the context of imperial personnel management, Tang elites believed that the emperor should place one in a position where one can make full use of one’s strength, and where one’s weakness might prove to be an advantage. For instance, if a region had recently suffered warfare, pillaging, and turmoil, then the ideal candidate for a governor would be one with a disposition capable of pacifying the region in the wake of chaos. Such a person might be ideal for such a region, but this does not mean that they would be ideal for every region. Let’s consider another example. Imagine a different region, where the previous governor proved ineffective and incapable of achieving anything. What would be useful would be a candidate with an iron heart, one who could really get things under control, right? So this is the idea—matching specific situations with specific talents—that underlies the seemingly formulaic language.

AC: Thank you, that’s really illuminating. To follow up, they have this system of knowledge for personnel management that they’re using to construct these edicts. This would seem to rely on the person doing the drafting knowing this system, but also the person who’s going to receive the edict. So, where do they get instructed in this system of knowledge? Is that something they’re formally taught? Is it just kind of abroad in the culture?

SY: During the seventh and eighth centuries, these appointees came from a very limited number of great clans. They were aristocrats; they were educated in certain ways; they read the classics; they shared a common language. But, from the seventh up to the ninth century, that changed because of the political-military situation. Appointments started to be made to people with different backgrounds. I don’t want to call them military men, that’s a misleading stereotype. But it is appropriate to say that they were leaders of their own troops. So they had followers, and they were not necessarily from the same pool of aristocratic clans. Some of them were from failing branches or lineages, while others were really grassroots; they were peasants who had fought bravely in certain battles, and who had retinues, followers. Gradually, they started to have small troops supporting them. For these people, they did not share this kind of language, this kind of knowledge.

Because the appointees came from different social backgrounds, with different mentalities, their knowledge and preparation of knowledge was different, precisely as you point out. It makes less sense to address them with the previous language. So, basically you have two options when the world changes that much. One possibility is to ignore the changes; employing the same language, you show your audience that the court is very persistent: everything has changed, but we are still here. That is one way of projecting imperial power: stability and continuity can mean something. Another approach, another possibility, is more pragmatic: things have been changing, and so it doesn’t make sense that we stick to old formulae, technology, ideology, or rhetoric. Wouldn’t it be more effective if we try to talk to these people with different backgrounds according to their own expectations? Those expectations were there for a long time, they weren’t new, but previously they were covered up with high-flown imperial rhetoric. So, does it make more sense if imperial edicts were altered a little bit to address concerns? And in that sense, does it make more sense to negotiate with them, to make a compact with them? That’s precisely what was happening in the early ninth century. There were certain edict drafters thinking through this idea and saying: “Well, why not? We should adjust to a new reality. The empire should adapt itself not only in terms of concrete political, administrative, and military measures, but at the ideological level as well.” This was a cultural form that people carried. Why not use that?

AC: You mention in the article that the An Lushan Rebellion is a sort of historical marker around which these changes started to appear in the edicts. Do you have further thoughts on the degree to which that was a causal thing, versus the degree to which these changes were independently happening at the same time but due to broader trends?

SY: Yeah, I would say the latter. So it was more of a continuity than a juncture or disjoint. Let me offer a little bit more background. The Empire of China was bizarre in the following sense: the emperor was hereditary, but bureaucrats were not. So, the emperor was a single person, ruling over a hereditary enterprise, and all his staff were appointed based on this system of personnel management I mentioned earlier. In terms of the beliefs that people held, a real question was: “Can I actually build a hereditary thing for myself? If I offer really important contributions to the emperor, can I receive a rank of nobility which is heritable?” Well, the short answer was yes, but the real challenge was whether something concrete could be passed to descendants. Not just a title or a rank of nobility, but territory. This idea was very important, especially for rising magnates who had their own retinues. This was something they really cared about.

They wanted to have terrain that they could pass on, and during the ninth century, they were trying to negotiate for prefectures. These were more valuable than counties, which were relatively small; a prefecture was relatively large. Long story short, some fiscal management was involved with prefectures, and one could have one’s own troops, thus making it more like a dynasty or regime. So, these magnates really cared about getting a prefecture. In the ninth-century edicts discussed in this paper, we don’t see the hereditary succession issue because the imperial documents do not address that. But what the officials really wanted was to earn a prefecture so that they had something that was theirs, something they could enjoy. The implication is that they wanted to pass it on to their offspring when they passed away, and the court was not really addressing that.

Allusions to those interests emerged in the late ninth century, and during the tenth century it became a big issue for empire builders. Regime builders need supporters, right? But their supporters really wanted to have something that was a hereditary enterprise. Going back to your question, what is interesting about that kind of highly formulaic, high-flown language is that it is embedded in specific periods. They are actually showing a certain mentality that can have longue durée significance; and that goes back to even broader questions concerning the merit of governmental documents for understanding not just cultural history, but also intellectual history.

AC: Thank you. We touched already on the two competing logics that you identify—the commoner-centered and the official-centered—and I would like to return to that. Is this distinction something you see contemporaries being aware of? Or is this distinction something that only becomes apparent after the fact, when we look at the edicts as historians and take a whole corpus? During this sixth- through ninth-century period, were people talking about the fact that edicts looked a little different, were making different arguments or were implying new things about leadership?

SY: Well, if there was language that explicit in the period, I would use that. But there was definitely some kind of contemporary awareness of that. The challenge is precisely that rewarding men with prefectures was considered not good from the perspective of mainstream statecraft. For that reason, in the received textual tradition, if you’re looking at treatises as historical narratives, people will say, well, it is a phenomenon but it’s wrong. They asked why does it happen? And their answer is that it is because these generals were greedy. Or that it happens because the emperors are either impotent or their decision-makers and counsellors did not know how to do things well. So this is a kind of contemporary discussion that is most direct in addressing that.

Moving up to the tenth century, we start to have more epitaphs. In this context, epitaphs mean a kind of funeral inscription. When a person died, a huge biography was carved onto a stone. This was a narrative that was a little bit more from the perspective of the deceased person, but still premised upon the literary tradition, as you can imagine. There, we start to see a bit more from the perspective of these men who fought, becoming aware that they expected certain rewards based on certain services, and that the reward often should be a prefecture or governorship. So the expectation, even though it was not written down, was more or less familiar to the players of the game. And what is really interesting is that, the rules being clear to the players, they were not recorded in the historical narrative, which in turn makes these documents particularly telling and important as historical sources.

AC: Thank you! How about its later legacy beyond the ninth, tenth century? How much of an echo down the centuries in Chinese history do we see from this distinction that you pick up here?

SY: Its importance is tremendous. So, I started this during my MA thesis. Back then, I already noticed that a lot of manuals were produced during later periods on how to write official documents, how to emulate them, how to imitate them. And, I didn’t really understand why. We are talking about sixth, seventh, up to the ninth century. They are specific events, specific documents. But then, in the fourteenth century, fifteenth century, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, not only in China but also in Korea and in other regions, they were writing the same prompts. Why were they doing that? This was kind of a by-product, something that I noticed but that I didn’t really understand while writing this paper, and it turned out to be a starting point of my later research.

So, this goes back to your question in the sense that the legacy is tremendous. In terms of the literary legacy, rhetorical knowledge based on the Tang legacy was produced from the fourteenth century. Elites were producing their own way of analyzing these edicts, how to divide them into three parts. So, I’m actually building upon their discussions, by dividing them into three parts. On the one hand, then, it is a rhetorical legacy of how to write a document. On the other hand, it is a legacy about political ideas. The idea became very . . . I don’t want to use the word constitutional, it sounds very value loaded, and nor do I particularly want to say contract-based either, as that seems very loaded as well. But let’s just say contract-based, especially starting from the tenth, eleventh, twelfth century, into the thirteenth century.

The idea is that individuals were employed. The emperor was a manager, he employed me, and then I offered my services and if I offered this amount of service, then a certain kind of reward was due to me. A big question I want to figure out is whether it was a kind of conceptualization of rights; whether it was contract-based, a kind of entitlement. That is basically the framework I use here and the one that became so important later. So, as long as I offer a service to you, something is due back to me, and this contract is right there in my appointment letter. This kind of mentality became really important not only in China, but also in many nearby regions.

AC: Great, thank you! To wrap up, you mentioned that this article has served as a lead into some subsequent projects, which prompts the question, what are you working on now? What comes next?

SY: Next! There are many things next! But directly related to this article is the big project, basically a monograph based on my doctoral research. Before going into that, I want to add that I started this article as a Tang history project and gradually it became more comparatively enriched. I want to emphasize that it shows the merits of going beyond a regional and dynastic focus. In this article, we are talking about official documents of the eighth and ninth centuries. But I think I came to a much better understanding of them after I have read and studied later rhetorical manuals on how to write the Tang-style edicts, especially those of the thirteenth century and onward. Although many modern and contemporary scholars have theorized the theme of reciprocity, I am no less indebted to early modern Manchu writings on this subject matter. The Manchus, as we know, originated in northeast Asia. They have their own language and conquered China in 1644. When translating Chinese chronicles into Manchu, they were offering interpretations of medieval Chinese history, including Tang personnel management. Overall, I think it is productive to engage these marginalized intellectual traditions.

In addition, I believe that it helps to think about things comparatively. And not just the familiar comparisons between China and Europe. I’m trying to do more comparison with Byzantine, Japanese, and some Persian material too. The Tang edicts made new sense to me when I started to translate Byzantine appointment documents and see the parallels, and then I gained new insights into these kind of Chinese documents. In brief, the longue durée, trans-dynastic perspective, critical attention to previously marginalized intellectual traditions like the Manchu, and what one might call world philology—that is, putting the Chinese documents, Latin documents, Byzantine Greek documents together—really pays off.

So going back to your question, I started writing my PhD dissertation around 2018, which basically originated from these documents. As we just discussed, I noticed that from the fourteenth to the eighteenth or even nineteenth centuries, many individuals were practicing writing the Tang edicts; not only those in China, but also the educated ones in Korea and Vietnam. There was once a curriculum that specifically trained individuals to produce documents in the voice of previous figures. It is a little bit like Renaissance humanism: you learn to recreate a document from the perspective of Cicero and so on. I want to understand how this curriculum took its shape, and in particular, I will argue that the Mongol tradition of employing scribes and valorizing scribal services played a pivotal role.

But what is really interesting is that it is also about political imagination. The politics behind the negotiation and making of an educational curriculum is always important but, for me, what is even more important is the fact that a curriculum, once there, creates countless imagining communities. Teachers and students, while teaching and studying the assigned or even imposed materials, came up with very creative ideas! It is this form of imposed intellectual creativity that remains most overlooked. In some cases, this training even promoted counterfactual imagination about real history. In 821, this political actor, this emperor, this minister, did this or that, right? Five hundred years later, when I am about to recreate this document, I want my political actor to do something else. In some cases, I want my political actress to do something else. If the emperor asked, “High palace lady, please marry the barbarian leader so that they will not invade us,” in real history the palace lady would say, “Oh, I have to accept my fate, however sorrowful I am.” But in rhetorical training, the writer could propose, “Nope, I don’t want to go, so I am writing a memorial, in this case, a formal official document saying: Emperor, you have important considerations, but I have my reasons. I decline.”

As such, directly related to this paper, there is a broader project about the reception of historical rhetorical knowledge. Particularly, it is about the institutionalization of rhetorical training and the reproduction of rhetorical knowledge that this kind of training fostered. These institutions and practices led to new kinds of political imaginations about what individuals said or could possibly have said in a very complicated bureaucratic system. In this sense, I am particularly interested in how the political imaginations of ordinary individuals in East Asia matter in our narratives of the history of political thought. So this is a book project that I’m working on.

Alexander Collin is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam where he works on northern Europe from the 1490s to the 1700s. His doctoral thesis aims to test the historical applicability of theories of decision making from economics and organizational studies, considering to what extent we should historicize the idea of “The Decision” and to what extent it is a human universal.

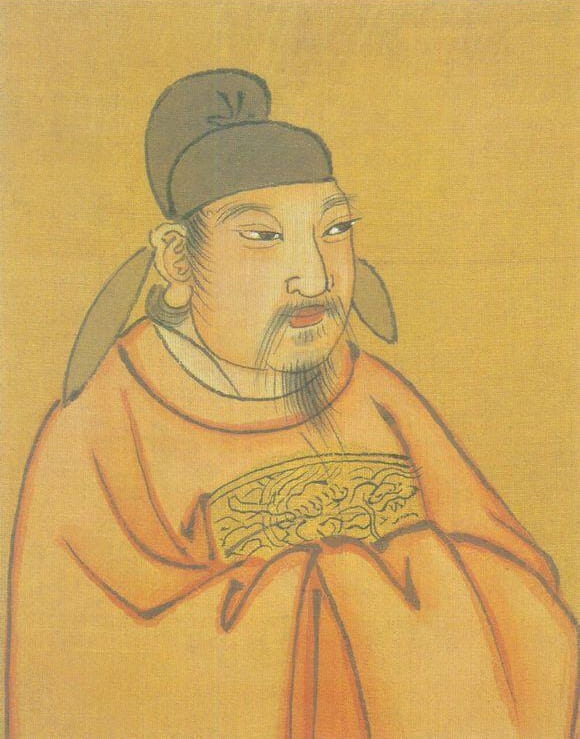

Featured image: Portrait of Emperor Xianzong (778–820), Wikimedia Commons.