By Jonathan Egid

Where would you go if you wanted to consult the largest collection of Ethiopian philosophical manuscripts anywhere in the world? Addis Ababa might be a good guess, at the national library or one of the universities. Perhaps elsewhere in the Ethiopian highlands, in the scriptorium of an ancient monastery – Debre Libanos or Abba Garima or one of the hundreds of monastic communities that line the shores of Lake Tana. Or, knowing something of the history of the expropriation of Ethiopian manuscripts, you might think to journey to one of the great libraries of Europe: the Bodleian and British Library both have large collections of manuscripts pillaged during the Napier expedition of 1867-8; or the Bibiliothèque Nationale in Paris, where the Irish-Basque explorer, geographer and linguist Antoine d’Abbadie assembled the largest collection of Ethiopian manuscripts of his day in the late 19th century. None of these however would be quite right.

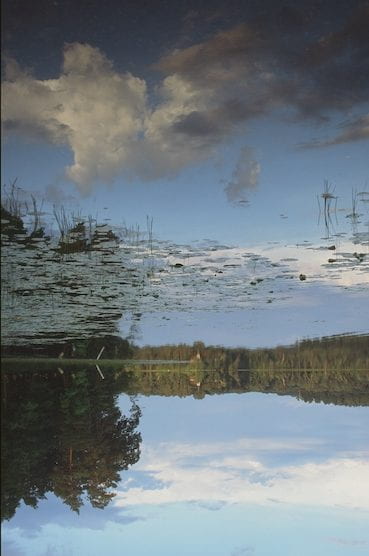

If you want to study the broadest, most comprehensive collection of Ethiopian philosophical manuscripts, you would need to travel to rural Minnesota. The campus of Saint John’s University is set in acres upon acres of green and blue. Located two hours west of Minneapolis, there are no towns of any size to the west until North Dakota, and no cities until the Pacific coast nearly one thousand miles away. The landscape is all lake and prairie and thick, primordial forest. There are chipmunks, deer and red squirrels, eagles and orioles and in the evenings the haunting cry of the common loon – Minnesota’s state bird and the creature which adorns the number plates of huge cars dotted across vast, empty parking lots. Saint John’s university grew out of Saint John’s Abbey, established in the mid-19th century to minister to German migrants, and today over one hundred monks still live there, taking daily mass in the hulking concrete spaceship of a church designed by the Hungarian modernist Marcel Breuer.

Opposite the church, across an immaculately manicured lawn is the university’s Alcuin Library, an elegant, if rather more understated building which houses the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML). The Manuscript Library began life as a repository for the preservation of at-risk manuscripts. Father Colman Barry, having witnessed the destruction of two world wars in and despairing for the bibliographic heritage of Europe if the worst fears of the Cold War came to pass, decided to begin a massive project of microfilming and acquisition from libraries in Austria, Spain and Germany. Over the years the focus of preservation was extended from Europe to the Middle East and Ethiopia, and then to the rest of the world. Today there are collections from Egypt, India, Iraq, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Malta, Nepal, Pakistan and Syria. The manuscript library hosts 400,000 digitized or microfilmed manuscripts.

I was at the HMML to study its Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML), a collection of 8,000 Ethiopian manuscripts – by some distance the largest in the world – photographed throughout Ethiopia from 1973 onwards. In particular I was after the collection of Fälasfa (philosophy) texts that had been gathered from collections all over the world, including the Vatican libraries and the Austrian National Library. The text itself, sometimes referred to as the Book of Wise Philosophers, is a compendium of philosophical maxims which seems to be a translation of a Christian Arabic gnomologium, now lost, entitled the Kitāb al-Bustān. This text is probably itself based on the Nawādir al-falāsifa, of the 9th century Nestorian Christian Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq. It may have a Greek original, now lost to us, but by now this is little more than speculation.

Over the years the text developed, or rather expanded, with subsequent generations adding or revising material such that earlier texts are far larger than earlier ones. All versions are written in Gə’əz, the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox church and the major literary language of Ethiopian Christian history, spoken in northern Ethiopia from antiquity until approximately the 13th century but which survives today only in the church.

Unusually for a Gə’əz text, the identity of the translator and date of the translation is known. Between 1510 and 1522 one abba Mika’el ‘the translator’ translated the text “by mouth”, that is, by orally translating the Arabic text into Gə’əz, with this text being copied by a scribe. Early modern Ethiopians evidently had a quite different notion of what counted as philosophy and who counted as a philosopher that contemporary academia, with not only familiar figures like Socrates, Plato and Diogenes dispensing wisdom, but also David, Solomon and the Ethiopian Saint Yared – the holy man who according to tradition founded traditional poetic composition (qene) and was taught the holy hymns of the Ethiopian church by three white birds sent from God. Much of the text is made up of back-and-forth question and answers between the wise man or wise men and the crowd:

ይቤልዎ፡ ለዲዮጋንዮስ፡ ጠቤብ፡ እፎኑ፡ ይእቲ፡ ሞት፡

And they said to Diogenes the Wise: how is this death?

ይቤ፡ መደንግዕት፡ ይእቲ፡ ለአብዕልት፡ ወመፍቅድ፡ ይእቲ፡ ለነዳይን።

He said: astonishing to the wealthy and necessary to the poor

Many of the philosophical reflections have the flavor of Greek philosophy viewed through the prism of Eastern Orthodox spirituality. One particularly striking example is the Ethiopian retelling of the story of Diogenes and Alexander the Great, in which the former rebukes the latter for stepping into his light. In the Ethiopian version, the details have all changed. Diogenes has become Socrates, and Alexander has become a nameless king. Diogenes-Socrates does not ask the king to move out of his light, but complains of losing the heat that is so vital for his thinking. But it is not only the details, but the overall atmosphere and tone of the passage that has changed.

Whereas earlier versions showed Diogenes-Socrates bluntly demanding the ruler step out of his light, the Gə’əz version delights in a kind of ironic misunderstanding: the philosopher explains to the King that the only real life is the spiritual life. The King fails to understand, believing that Socrates is complimenting him in speaking of the temporal world of power and riches. Indeed, the philosopher and Ethiopianist Claude Sumner exaggerates only a little when he says that “one seems to be listening to an Oriental monk speaking through the mouth of Socrates” (30).

Other sections of the Book of Wise Philosophers focus on more traditionally philosophical topics like human nature and what makes human beings distinctive from other natural beings:

ይቤ፡ ፩እምጠቤሃን፡ እስመ፡ ሰብእሰ፡ ኢይትሌለይ፡ ወኢይክብር፡ እምነ፡ እንስሳ፡ ዘእንበለ፡ በንገብ፡ ወልቡና፡ ወእመሰ፡ አርመመ፡ ወኢለበወ፡ ኮነ፡ ከመ፡ እንስሳ።

One of the wise men said: ‘because a man is no better and no more honorable than an animal except with speech and intelligence, if he is silent and does not think, he becomes like an animal’

The interest in animals recurs throughout the Fälasfa, and is apparent too in some of the earlier works translated from Greek into Gə’əz like the Physiologos, a compendium of nature mysticism most likely composed at the turn of the 3rd century in Alexandria. The Physiologos treats in each of its 48 chapters an animal, plant or mineral, describing its appearance, habitat and its natural and spiritual properties, often providing an allegorical interpretation of these properties along Christian lines: the phoenix rises from the ashes like Christ, the pelican that sheds its own blood that its progeny may live again. The work was almost certainly translated directly from Greek into Gə’əz in the Aksumite period, and thus constitutes the earliest work of natural history, and of philosophy in the broad sense, in Gə’əz.

Some sections of the Fälasfa however use the picturesque adaptation of philosophy to an Ethiopian context in order to make less savory points:

ይቤል ለሰቅራጥ፡ አይኑ፡ አንበሳ፡ የአኪ፡ እምነ፡ አናብስት፡

Socrates said: “which lion is most evil from among the lions?”

ይቤ፡ አንስታያዊት።

He said: the female

Given the rather mixed bag of insights to be gleaned from the text – why bother with the Fälasfa? Why travel to Minnesota to read the Fälasfa, an Ethiopian translation of an Arabic work that recounts apocryphal stories about Greek philosophers? On the one hand it is a fascinating example of how a text metamorphoses as it crosses geographical and linguistic boundaries. It is a fascinating example of the reception of Greek thought in a part of the world rarely assumed to have much of a philosophical heritage at this early date, and of the processes of the indigenization of cosmopolitan knowledge.

But despite the intrinsic interest of the text, in truth, I was not here for this book alone, but on the trail of another, even more enigmatic work. My doctoral research focuses on the century-long debate over the authorship of the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob, a philosophical autobiography set in 17th century Ethiopia, that has been acclaimed both as the ‘jewel of Ethiopian literature’ and as a fake. The Hatäta is a work which has over the last century become embroiled in a seemingly intractable and highly emotive debate about its authorship, namely whether it is the authentic product of a 17th century Ethiopian scholar, or a later 19th century forgery by a lonely Italian monk, stranded in Ethiopia

Sumner, who took the Fälasfa as the topic for the first volume of his magisterial, five-volume Ethiopian Philosophy, and the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob as the second, suggested that in these early works we see the trickle that would eventually become a great river. Even as translations, the Book of Wise Philosophers is an Ethiopian work, he argued, on account of the way that it was transformed in the process, acquiring a distinctively Ethiopian character: “this work is Ethiopian, not by the originality of its invention, but by the originality of its style and presentation.” This is, according to Sumner, because “Ethiopians never translate literally: they adapt, modify, add, subtract. A translation therefore bears a typically Ethiopian stamp: although the nucleus of what is translated is foreign to Ethiopia, the way it is assimilated into an indigenous reality is typically Ethiopian.”

I was in Minnesota to examine the development of a philosophical lexicon in Gə’əz, the language of the texts and the dominant literary language of Ethiopia for most of its long history. I wanted to see if there were traces in these earlier text of the ideas expressed in the masterwork of Gə’əz philosophy, the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob. The debate over the authorship of the text had until recently become bogged down in accusations of bad faith on either side, and I hoped to open up a new avenue of exploration by examining the philosophical vocabulary (basically the set of terms that do the philosophical ‘heavy lifting’) employed in the text, and seeing whether this vocabulary could be better explained as translations of European philosophical terms (which would be the case if the text were a 19th century forgery), or the developments of earlier Ethiopian works like the Book of Wise Philosophers (if it was the ‘authentic’ [product of a 17th century Ethiopian scholar). In particular I was looking for the word that is the lynchpin of the philosophical system of the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob, the word ልቡና (Lebuna), denoting the faculty of reason, intelligence or understanding.

I was in luck. The term was used no less than four times on the very first page of text, in ways that seemed, if not identical, at least recognisably similar to what I had been expecting. Of course, the appearance of a single term proves nothing, and even the appearance of many is inconclusive, but it begins to lay the ground for an argument that the text could have been from 17th century Ethiopia as the relevant concepts were already in use in Gə’əz, that they were not on the one hand, totally unthinkable in the context of 17th century Ethiopia, nor created ex nihilo by an individual genius living alone in a cave.

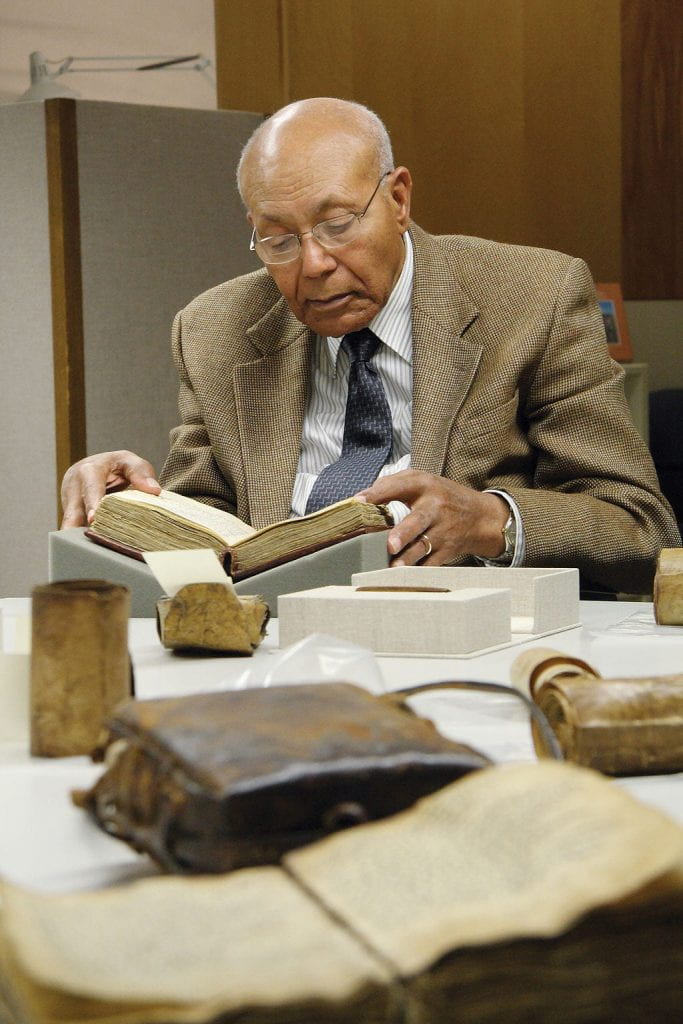

My only regret is that I was unable to consult a resource at least as great as the manuscript collection. For most of the last half century, Collegeville was home also to one of the greatest scholars of Ethiopian manuscript culture, the late, great Getatchew Haile who died in 2021. Getatchew was one of those thinkers whose scholarly output beggars belief: hundreds of catalogs, editions, articles, translations into and from Ethiopian and European languages.

Born in Shewa in 1931, just a few years before the Italian invasion, Getatchew studied Semitic philology in Cairo and then Tübingen, returning to his home country on the eve of epoch-making changes – the first coup had been attempted against the government of Haile Selassie. The ancient Solomonic dynasty of which that emperor was to be the last was not long for this world. After the revolution of 1974 brought the Derg regime to power, Getatchew found himself on the wrong side of the junta, and during a shootout with their forces was paralysed in the lower back. With the help of friends he escaped his hospital, then his homeland, fleeing first to London and then to the United States, where he settled in a small town just outside the St John’s campus. I can only imagine what this Ethiopian-born, Egyptian-educated scholar must have made of his first Minnesota winter.

Over eighteen years between 1975 and 1993, Getatchew took to the 8000 microfilmed manuscripts from the EMML project, which he meticulously cataloged and made available to the scholarly community. The final part of this project was supported by the MacArthur ‘genius’ grant, making him the first African to receive this coveted award. Most interestingly for me, Getatchew agreed for many years with the prevailing scholarly consensus on the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob, namely that it was a forgery, until late in his life something made him change his mind.

In 2017, Getatchew published an article in a collection dedicated to his friend, the Amharic language poet Amha Asfaw, arguing in favor of an Ethiopian authorship of the Hatata. I had hoped to speak with him about his change of heart: was it just reviewing the evidence, or was there some deeper hunch informing his opinion? What did he think about recent work on the topic (selfishly I wanted to know what the great man thought of my own small contributions)? Did he think there was any way of settling the problem once and for all? But as it stands, with regard to both the Hatata debate and Getatchew’s own thoughts on the matter, we have nothing but the words on the page, and no option but to advance his work in our own small way. Getatchew Haile’s tombstone rests in the cemetery just outside the St John’s campus, with Gə’əz letters in a peculiar, ornate style carved into the smooth reddish granite opposite Lake Saganatan. This quiet, peaceful place, a land of plains and lakes and forests, has become in the twenty first century a repository for the traces – in handwriting, stone, in lines of code – of the literary and philosophical traditions of an Ethiopia that is in many ways its opposite.

Jonathan Joshua Egid is a graduate student at King’s College London. His research explores philosophy and its history in a global orientation with a special interest in the methodologies of intercultural comparison and the historiography of philosophy. He is currently writing about the Hatata Zera Yacob, an enigmatic philosophical autobiography from Ethiopia, and the century long controversy over its authorship. His latest article ‘How does philosophy learn to speak a new language?‘ appeared in Perspectives.

Edited by Isabel Jacobs

Featured Image: Lake Sagatagan. Photo: Jonathan Egid.