By Elena Barattini

It was the 19th of April 1840. The Villanueva, a packet boat flying the Spanish flag, dropped anchor in the flocked harbor of Havana. Fifteen passengers disembarked and stepped foot on Spanish territory. Among them, there was an Italian traveler, getting acquainted with the bureaucratic procedures of the colonial government and the two routine British inspections of the vessel. In fact, as all male passengers were requested to present a papeleta (document) to reach the mainland, two groups of British officers had already fathomed the craft, looking for dreadful proofs of “dealers in coal”: slavers with human cargo.

Never object of a systematic study, quoted, and read just by a few scholars, Carlo Barinetti’s Voyage to Mexico and Havana provides in-depth, although extremely biased, descriptions of the everyday management of economic activities in Tampico, Mexico City, Veracruz, Puebla, Havana, and New Orleans. Carlo Barinetti’s work might be described as a detailed first-hand traveler account of the political landscapes of some of the main trading posts in the Americas in the first half of the 19th century. Skillfully mixing his critique of the present situation of pre-unitary Italy, and his juvenile aversion to the Austrian control of his homeland, the Lombard-Venetian Barinetti defined himself as a convinced liberal. A young enthusiast for the cause of a united and self-governed Italy, he then moved to the pre-Civil war United States, where he taught modern languages, and eventually obtained citizenship.

From there, he sat sail south. Ending up in Havana in the 1840s, his travel accounts are a powerful harbinger of positions which legitimized the Escalera repression, a mass-punishment of free people of color that followed a summary trial that raised alarm of a suspected plan to end slavery and Spanish rule in Cuba in 1843. Quintessentially political in the observations of what in his opinion did and did not work in the territories he visited, his text represents a key and underrated source for the study of ideas, political forms, and their circulation in the first half of the 19th century Atlantic world. Still intimately linked to the history of power, his literary production reflects his take on that crucible of happenings capable of keeping a privileged, educated, white man awake all night: the Haitian Revolution. As he provided details on the extremely severe measures implemented to police non-white subjects on the island, his words are deeply informative on the broader, generalized, sense of panic surrounding the long wake of happenings that linked La Escalera to the 1791 revolutionary experience.

Walking around Havana, “a place so well known to the Americans”, Barinetti took notes on the “kind of prosperity which shows itself at every step, which render that city highly agreeable and interesting”. The prosperity in question was all bloodstained, made by enslaved people’s hands and sweat. The tons of sugar once produced in French Saint-Domingue were now put on the market by Cuban ingenios (sugar mills) owners. Thousands of enslaved people, who would have once been principally deported a few maritime miles south, were now directed to Cuba, amid what has been defined as “second slavery”.

In the intertwined histories of the Haitian Revolution – the largest slave uprising the world has ever seen and the only one that led to the formation of an independent state in 1804 – and the sugar revolution in Cuba, concern and optimism influenced the behaviors of enslavers, travelers, and property owners. On the one hand, in the era of the Saint-Domingue uprisings, there was a “common wind” among the men and women of the African diaspora, characterized by the diffusion of empowering concepts, such as freedom and the abolition of slavery. On the other hand, the recurring metaphor of the fear of contagion, and a constant terror of retaliation meandered through the cities and the plantations of the Caribbean. This constant state of panic went hand in hand with the increase of the enslaved population, especially as the wealth that could be destroyed during such uprisings grew.

Haiti was thus instrumentally invoked to ideologically reinforce slavery in Cuba, emphasizing a “dangerousness” intrinsic to the individuals deprived of their freedom. This was reflected in the strict regulation and the increased surveillance imposed on the free and enslaved population of color on the island. Four years before the Escalera repression, the clase de color (people of color) of Cuba after a given hour had to “be at home, while no assembly of colored people is allowed after sunset; not even two can walk together or stand in the streets” as Barinetti attentively wrote down in his notebooks. The Haitian specter hovered around the island of Cuba, and the constant worry of a mass gory riot of the enslaved affected the very act and portrait of traveling as depicted by the Italian. A “sudden rising” was expected at every corner of the island. Travelers wandered armed, counting on a steady intervention on the part of “a couple of Spaniards or Creoles on horseback” who could “attack and subdue a band of fifty or more slaves, though the latter are generally armed with machetes, or long knives, which they use to cut the sugarcane”.

Not surprisingly, the liberal Barinetti spent several pages on the virtues of the free States in the North of the Union, on free trade and labor. Indeed, his thoughts on abolition are exemplary of the gradualist positioning shared at the time. Recurring to different sets of notions which were structured according to racial precepts, Barinetti shivered at the thought of a black population outnumbering the white one. When describing the misery of the enslaved in Cuba, Barinetti also invoked family separations, the hideous travel across the ocean, the severe physical punishments, and the constant noise of the lash hitting somebody’s back. However, these abolitionist topoi were not mobilized to advocate for immediate emancipation, quite the opposite.

Broadly referring to Cuba and the south of the United States, Barinetti argued slavery simply could not be abolished at that moment: time was not yet ripe.

“Come! come here abolitionists! emancipate them, spread knowledge among them, give them equality of rights, and you will see the result. Release them from the natural bonds which form the bulwark behind which the whites feel sheltered, and then what makes me shudder if I only think of it will happen.“

Echoing Barinetti’s warnings, from the 1810s to the 1840s the different governors of the Capitanía General de Cuba (General Captaincy of Cuba)put in place harsh preventive measures, safeguarding the nights of sleep of the enslavers, the plantation owners, and colonos (settlers). These policies severely impacted the already constrained agency of enslaved men and women, and free people of color in Cuba. Being black, in the eyes of planters, creole thinkers, and travelers among which Barinetti was no exceptional teller, equated to being on the verge of plotting a Haitian-style fierce uprising. Nonetheless, the relentless rules detailed by Barinetti and his peers were only the beginning.

The mere presence of enslaved and free people of color, walking on the streets of Havana, busy in their numerous occupations, progressively became a serious threat posed to the maintenance of the colony’s social order: the terror took over. Barinetti was not the only one “shuddering”, and the colonial elite was unwilling of taking other risks. The number of deported people from the African continent was augmenting, notwithstanding the treaties with the British and their navy, as the Italian traveler repeatedly underscored. Measures were to be taken, locally. Cuba became a relatively safe harbor for slave owners (and their lucrative economic activities), for it offered an escape from their plantations in Saint Domingue which were quite literally burning since the end of the 18th century. All the while, networks of formerly enslaved and free-born people of color (libres de color) who traveled around the Caribbean were formed. With them, so did ideas of liberation, of living according to one’s own terms. However, they did not level the Haitian terror, together with its harsh social and economic consequences, hunting the very existence of black people around the globe for centuries.

Just three years after the publication of Barinetti’s travel accounts, authorities in Cuba put on an exemplary mass punishment, to the detriment of the libres de color, and particularly targeted to once and for all discourage potential efforts of aligning Cuba’s destiny with that of the former French colony. Gone down in history as the Conspiracy of La Escalera, a scheme supposedly plotted by libres de color of African descent, as well as slaves, creoles, and British abolitionists to burn the bridge built by Spanish rulers in Cuba through the institution of slavery, the 1843 event went down in history as a bloody massacre that ended the lives of thousands. Taking its name from the “ladder” (escalera) employed to break down potential suspects, the alleged insurgency, with the enslaved revolts in western Cuba, have been given great scholarly attention, as has been the case, more recently, with the unutterable repression that followed in January 1844.

Far from being an isolated, blood-soaked, singular episode in the history of Cuban slavery, the terrain around the repression specifically dedicated to the Escaleraconspiracy had been prepared for years, as Barinetti’s notebooks display. The increased militarization of the island began with the 1837 Constitution – expressly stating the will to administer Cuba through so-called “special laws” – the curfew, the unbearable working conditions on the plantations, and the construction of the barracoons all contributed to the muscular violence enforced in repressing the potentially revolutionary Escalera plan. In this respect, Barinetti’s work, printed in New York, circulated in the United States and, most likely, in Italy as well, is particularly significant because of its capacity of foreshadowing future Atlantic happenings. Indeed, his “tremors” were widely shared. Captain General Leopoldo O’Donnell, for example, would make sure he did all he could to eradicate any revolutionary febrility plaguing the island. A dramatic break for the libres de color’s relative autonomy, La Escalera repression was the result of a longstanding repressive apparatus which had been patiently built by Spanish and other foreign viewers who reproduced systematic racism. Works like Barinetti’s shed light on the context surrounding the upcoming repression and emphasize the ideological and material preparation that was enacted through institutions and actors who actively prompted the growth of a rampant anti-black and anti-slave sentiment.

In the aftermath of the Escalera repression, the libres de color in Cuba lost almost all their economic stability, military standing, and everything related to their already precarious social status. However, the impressive resilience shown by the Afro-descendant community in Cuba strenuously proved the weaknesses of O’Donnell and the slave owners’ attacks on black populations.

Indeed, ideas on freedom and emancipation from masters and mistresses, which were far from mild and reconciliatory, did stick around. They dot the juridical transcripts presented to the courtrooms by the enslaved and were embodied in everyday forms of resistance. In the interstices of standard wording, and formal juridical formulas, enslaved men and women in Cuba spoke up in the tribunals, asserting their rights to be heard. Presenting family reconstruction lawsuits, negotiating the time and conditions of their labor, protesting the vexations of their enslavers, their petitions brought conflicts over race, gender, and power relations directly into the seats of colonial institutions. Over this unequal jurisprudential terrain, gradual emancipation, albeit partial, fragmented, and precarious, was being constructed well before the official royal proclaims that sanctioned a transition out of slavery in 1870 with the free womb law, and ending in 1880 with the abrogation of the patronato (forced apprenticeship) institution.

Barinetti’s travel writing is thus a privileged lens for exploring the entanglements between the Haitian Revolution’s heritage and the Escalera repression. Presenting conversations with doctors, slave and property owners, as well as functionaries, Barinetti’s text reconstructs the extremely abusive context that configured black people’s everyday lives in 19th century Cuba. However, by reading his work against the grain, the actions of the enslaved themselves stand out all the more, forged by experiences of coercion and violence, while being projected towards the construction of an aftermath that eventually tore down the legitimacy of such institutions.

Elena Barattini is a Global History of Empires Ph.D. candidate at the University of Turin, Italy. Her work examines the legal petitions filed by formerly enslaved women in Cuba, within the Patronato law framework. Her primary research interests are the history of labor and coercion, the place of gender in it, Atlantic slavery and the colonial history of the island of Cuba.

Edited by Matias X. Gonzalez

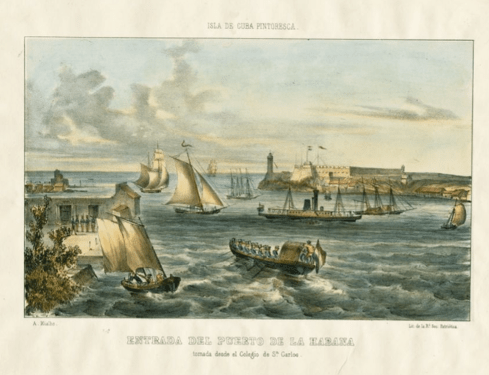

Featured Image: Entrada del Puerto de La Habana tomada desde el Colegio de Sn. Carlos. (Entrance to the Port of Havana taken from San Carlos School). Artist: Mialhe, Frédéric, 1810-1881 Lit. de la Rl. Sociedad Patriótica, 1839. Courtesy of University of Miami Library Digital Collection.