By Artur Banaszewski

David Broder is a historian of the Italian far right and Jacobin’s Europe Editor. He is the author of The Rebirth of Italian Communism and First They Took Rome. David’s newest book Mussolini’s Grandchildren examines the history and ideology of neofascist movements in Italy after the Second World War.

Artur Banaszewski: In the 2018 film Sono Tornato (“I have returned”) Benito Mussolini, played by harrowingly believable Massimo Popolizio, appears in present-day Italy and launches an unexpectedly successful campaign to reclaim power. The film serves as a warning that fascism is an ever-present threat – and thus follows the narrative of numerous public figures and academics. However, in your book, you strictly distinguish between historical fascism and postfascism. What is the difference between them?

David Broder: In the film, Mussolini is a fantastical figure that suddenly falls from the sky and finds political support from nowhere. When there is international media alarmism about the far right – not only in Italy – there is this idea of a sudden upsurge and breakthrough, a return from the past. It is true that Fratelli d’Italia as a party has enjoyed a very rapid electoral rise. But at the same time, the conditions for that to happen have developed over decades, and are to be understood in terms of Italy’s postwar history.

As I show in the book, Fratelli d’Italia is the continuator of a long tradition, which its leaders call the “seventy-year tradition of the Italian right,” yet also separates this out from the regime period itself. This is what I call a postfascist tradition. Postfascism is a movement rooted in historical fascism, but which simultaneously claims to have transcended it to have become a normal, national-conservative party. However, the fact that this tradition has persisted for 70 years does not mean it stayed the same. The contemporary far-right operates in a very different world from that from which fascism originally emerged, and my book tries to capture this generational change. Hence the title: Mussolini’s Grandchildren.

Postfascism shares important characteristics with historical fascism: the same political culture, focus on the past, the use of history as a theme of identity… But its political platform is not the same as in the era of revolution, social violence, mass mobilisation and grand utopianism. It is a harsh identity politics and an ethnic conception of nationhood, but which it pursues within a liberal constitutional order and a (somewhat depleted) democratic framework. Even though there are also some more militant elements in its base that use political violence.

AB: You emphasize that the founders of the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) – the principal neofascist party in the post-war period – were veterans of the Nazi-collaborationist Italian Social Republic (Salò Republic) founded by Mussolini in 1943. Until the 1990s, the party was widely marginalised yet nonetheless managed to retain its institutional and ideological continuity. How did the MSI succeed in that, unlike other far-right parties in Europe? What ideological choices did it make to ensure that continuity?

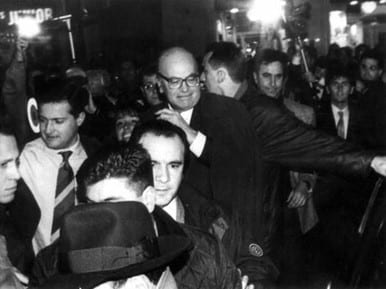

DB: I think the fundamental limit of the MSI as a party in the post-war period was very closely connected to its strength. Namely, this was the fact that it was effectively unable to enter the national government – and, simultaneously, had its main enemy in a much larger party, the Communists, that also could not enter government. When the MSI tried to passively support the government of Fernando Tambroni in 1960, the backlash was so great the right wing of the Christian Democrats realized this alliance was not an option.

These combined structural factors of the First Republic – what we call the period in Italy between 1948 and 1992 – allowed the MSI to preserve its identity rooted in historical fascism. Its members had a strong sense of victimhood of the camp of the defeated, which created a certain self-regarding language – such as “exiles in the fatherland” (esuli in patria). So, both a marginalized movement, but also a hard core. This was based on a shared experience, yet the MSI adopted the idea of introducing innovation and change while remaining rooted in the past, which is typical of the postfascist tradition. Already at the 1948 congress Augusto de Marsanich, one of the founders of the MSI, introduced the famous slogan: “‘we will neither restore nor renege on the regime.” Similarly in the 1990s, when Gianfranco Fini said about the MSI “we have become postfascists,” he drew on this language of not reneging on their past but moving on to the future. The MSI believed that to keep fascism alive, they had to modernize and renew it for the future.

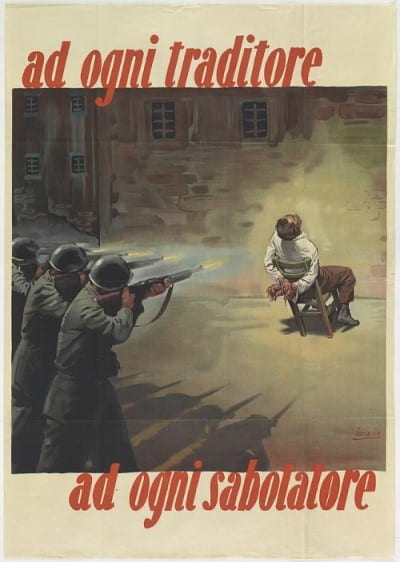

Simultaneously, fascism as a political culture is syncretic and has many different elements. This is visible even in the postwar effort to centre the party’s historical identity on Salò. The Salò Republic stands in the MSI tradition as a moment of the possibility of real and higher fascism. It symbolizes the idea of original social fascism, of the Sansepolcrismo of 1919, which finally broke its relationship with the old, liberal Italian state and became more totalitarian. Parts of the MSI saw Salò in that light: as a lost revolution. Yet, in postfascist memory culture, there also existed this idea that “they fought for Salò even though they knew that they would lose,” out of generous and selfless patriotism. Historian Francesco Germinario quotes this being encapsulated in the idea that “their side, the Resistance, fought for una fazione, a faction, whereas we fought for la Nazione, the Nation.”

Also typical of the MSI tradition was its ability to hold together different “souls” of fascism: some more national-conservative, some more “social” or even anti-capitalist. On one hand, it was an outwardly divisive and confrontational political movement; simultaneously, it presented itself as all-encompassing and purely patriotic. The fact that the party was never in government, that it remained embattled and extreme, allowed these contradictions to remain contained.

Simultaneously, the MSI was allowed to participate in democratic institutions as long as they did not create an armed struggle movement. On these grounds, the 12th transitional provision of the Italian Constitution prohibiting the reorganization of the Fascist Party was never used against them. But when in the 1990s, after the Communist Party had dissolved itself, and the largest parties of government – the Christian Democrats and the Socialists – collapsed following the Tangentopoli scandal, the MSI became able to say: the First Republic has fallen, and we are the only party to have been honest.

AB: You mentioned that fascism is a form of political culture. In the post-war decades, it was countered by the antifascist memory culture – central to the identity of the First Republic. However, after the 1990s, antifascism ceased to be a unifying national myth, while the far right has been increasingly successful in promulgating its narratives. How did this change in Italian public memory culture occur?

DB: Of course, the antifascist culture has not disappeared entirely, far from it. But I think the change at the institutional level was primarily caused by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the explosion of contradictions within the Communist Party. In the 1990s, even prominent ex-members of the Partito Comunista Italiano became reflexive anti-communists. They began accepting ideas about the criminality of communism and right-wing talking points: “the communists in the Resistance did bad things, too.” As a result, this type of international “twin totalitarianisms” theses replaced the antifascist paradigm of the post-war Republic.

This is not to say that only neofascists opposed the antifascist paradigm. There have always been monarchists or other conservative forces which fought against antifascism, presenting it as a communist idea. But I think the MSI’s historic mission was to replace an antifascist paradigm with an anti-communist one. While initially, they failed, in the 1990s, they attempted to replace both with paradigms with a general condemnation of dictatorship. In the Fiuggi theses from 1995, the MSI’s successor Alleanza Nazionale called for a dissolution of all fasci and for an end to both fascism and antifascism.

As I show in the book, the idea that fascism is reduceable to dictatorship or antisemitism, and can be condemned solely on these grounds, is a very reductive reading of what fascism is. The postwar MSI’s neofascism described itself as more than violence, repression, or racism – but as a political culture. The latest generation of memory culture in Italy does not “leave fascism to the past,” but is a continual process of rewriting and revising historical memory.

AB: When asked about fascism, members of the Italian far right usually say that fascism should be “consigned to the past.” Simultaneously, you point out their efforts to rewrite Italian history – particularly the history of communism. What role does this historical revisionism play in the political strategy of the far right, not only in Italy?

DB: Of course, there are different types of historical revisionism, which may be more or less legitimate. But the type of revisionism that the far right advances is, factually, a falsification of history to instrumental political ends. In the Italian case, the history of communism must be told in a certain way to create a false parallel between communism and fascism – thus presenting antifascism as itself illegitimate.

In my book, I discuss the role of the foibe – the mass killings of Italian fascists and civilians by Yugoslav partisans during and after World War II – in rebalancing the Italian public debate away from antifascism from the 1990s onwards, including by undue comparisons between this history, “ethnic cleansing” in Yugoslavia, and even the Holocaust. Eric Gobetti has written a great book titled E allora le foibe? – because that phrase, “so what about the foibe,” is used in Italian public debate to criminalize the Left and focus attention on its violent past.

In Mussolini’s Grandchildren, I also present how this argument is applied to the discussion on immigration. The far right often claims that “us, Italians, have always been victims of ethnic cleansing,” and the destruction of national culture has always constituted the basis of genocides. Through this lens, the idea of a supposed “immigrationist” plot against Italy is presented as a continuation of past communist crimes, today trying to destroy the Italian nation by removing its homogeneity.

We can see similar processes in other countries. Across Central-Eastern Europe, particularly in the context of the war in Ukraine, there has been a movement to tear down Red Army statues. The fight over historical memory is a central stake in defining the political terrain, and even who has the right to participate and speak in a democracy.

AB: In your book, you say that the Italian far right recomposes specifically fascist ideas and historical references in the present within nationalist identity politics geared to postmodern times. You draw parallels between the postulates of Fratelli d’Italia and the policies of far-right governments in Hungary and Poland. Yet not once in your book do you use the term “populism” to describe these political phenomena. Why?

DB: I will admit that I have used this term before, sometimes even in a positive sense. I see populism as a political style of messaging and mobilisation in an era of disillusionment with mass, structured organisations. But at the same time, the term “populism” has two major flaws. One is the creation of a misleading dichotomy between mainstream and outsider parties while ignoring the fact that phenomena such as Emmanuel Macron’s first presidential campaign or Matteo Renzi’s leadership of the Democrat Party adopt many of the same rhetorical attributes.

The other is the tendency to group together entirely different political movements – such as the radical left and radical right – which has a banalizing effect related to a certain age of the development of politics and media. For instance, if a politician of the Left says that for the past decades, wealth distribution has been going in the wrong way, and an increasingly smaller number of people control all of the world’s resources in an environmentally destructive way – and then you take a statement that George Soros, the “usurer” and “speculator,” is concocting a global and globalist plot to destroy the ethnic basis of our society and turn us into amorphous slaves to finance capital – then I think describing both these statements as “populist” tells us nothing about what they mean or where they come from.

I am a part of a strand of historical reading of contemporary political phenomena. I consider Fratelli d’Italia as a party rooted in fascism but one which has also changed its expectations and forms of actions over time. For instance, the adoption of great replacement theory is not specific to postfascist tradition alone – it also exists across other parties with a more conventional conservative past. On this basis, I think the idea of a” populist outsider” limits our understanding of Fratelli as a political phenomenon. As I have mentioned in the first question – the far right did not suddenly appear from nowhere. It has benefited from a long process of fusion, creation, and innovation across large swathes of the international Right during a moment of preoccupation with civilizational decline, which surely has historical antecedents but also forms a new kind of identity politics today.

AB: What you have said indicates the pivotal role of history in the far right’s political strategy. What should be the responsibility of professional historiography and critical historians towards far-right narratives that instrumentalize history?

DB: In the book, I say that the Fratelli d’Italia have a politically instrumental use of history… But what I mean is that they are falsifying history to their political ends. The use of history for political ends in itself is not objectionable – in fact, I think it is unavoidable. Because Fratelli do want to talk about World War II. They do not want to leave the past in the past. This is why the regional governments controlled by right-wing parties deny funding to the institutes that do not support their revisionist reading of history. Or why they incite debates about the books in public schools in libraries. This is the substance of politics that is not only of interest to historians.

A historian’s job is to write critical and well-documented history, which can inform and filter through public debate. There is value in the historical reconstruction of even recent politics. I hope my book offers ways of reading fascism as a historical phenomenon while documenting all recent debates and controversies that allow us to understand what the party really is.

Artur Banaszewski is a PhD researcher in the Department of History and Civilization at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. He holds a Master of Letters degree in Global Social and Political Thought from the University of St Andrews. Artur’s doctoral project titled “Disillusioned with communism. Zygmunt Bauman, Leszek Kołakowski and the global decline of orthodox Marxism” explores Eastern European critiques of socialist thought and intersects them with the global political context of the Cold War. His research interests include global intellectual history, postcolonial studies, political theory, and Cold War liberalism.

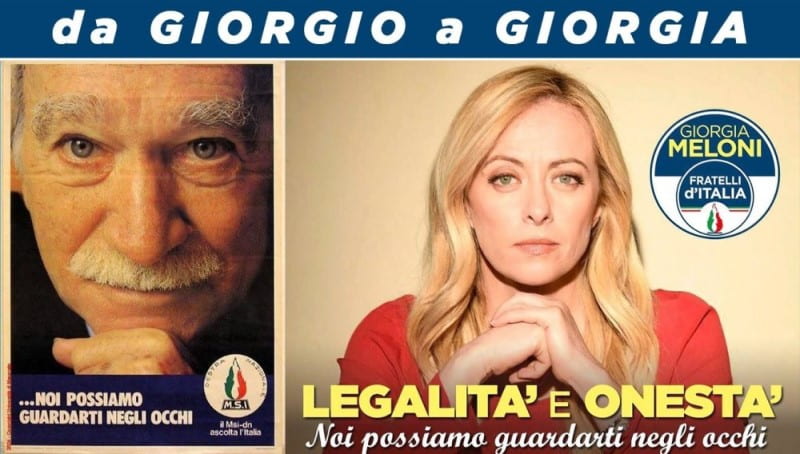

Featured Image: Poster depicting Giorgio Almirante and Giorgia Meloni reading: From Giorgio to Giorgia, we can look you in the eye. Courtesy of the official Facebook profile of Fratelli d’Italia.