By Carolyn Mackie

“You have bewitched me, body and soul, and I love–I love–I love you.” Jane Austen’s character Mr. Darcy never actually utters this line in her 1813 masterpiece Pride and Prejudice but placed in the mouth of Matthew Macfadyen in the 2005 movie adaptation, this line has become iconic among fans, spawning fan art, t-shirts, and whole lines of giftware. Although the meaning of Mr. Darcy’s sentiment is still clear to contemporary viewers—his whole person is completely under Elizabeth Bennet’s thrall—the framework of “body and soul” as an account of the human person would have already been out of date in philosophical circles by 1813. The rise of materialism in the last several centuries has made claims to such a framework tenuous. However, the concept and language of the “soul” as a more-than-physical element of human personhood continue to linger in popular culture and in many religious and spiritual traditions. Christianity, in particular, has a long, complicated history with the soul and played an important role in advancing this dualist body/soul anthropology in Western thought.

Birthed out of Judaism and heavily influenced by Greco-Roman thought, Christianity drew on these traditions as it established its own unique identity and doctrines. The concept of a separable, immaterial soul is not found in the Hebrew Bible. The Hebrew word nefesh, usually rendered as psuchē in the Septuagint and “soul” in English translations, is closely tied to the terms for “breath” and “to breathe,” particularly the breath that God breathed into the first human (Gen: 2.7). Benjamin P. Blosser describes nefesh as referring to “the totality of conscious, bodily life” (208), a definition that is consonant with the biblical text’s focus on the human as “embedded in a community, and a communal history” (208). Under Hellenistic influence, Jewish thought eventually expanded to include the idea of a soul, but this was always couched within this fulsome concept of an embodied, embedded human person (209).

In contrast to Jewish thought, Greek philosophy had well-established notions of a separable, immaterial soul, particularly in the Platonic tradition. As Christianity developed, its thinkers borrowed from Greek traditions and adopted a body/soul anthropological structure. Yet this did not entail a wholesale acceptance of Greek anthropology. Christianity’s Jewish roots, as well as its central claims of incarnation and resurrection, resisted body/soul dualisms, at least to the extent that these were hierarchical, denigrating the body and elevating the soul, or prone to divide the human person too sharply. The Christian Gospel of John opened with the outrageous (to Greek ears) affirmation that the logos had become sarkos—flesh—in the person of Jesus Christ (John 1:14), thereby granting flesh an essential significance in the new religion. The equally startling contention that Jesus had been resurrected from the dead, so central to the proclamation of the new faith, meant that bodies had enduring importance after death, a claim that ran counter to prevailing Greek anthropologies, which tended to see death as releasing the soul from the encumbrances of the material world. That bodies were good had to be accepted to make sense of these new Christian beliefs. This did not stop groups such as the Gnostic sect from arising within Christianity and asserting that human bodies were inherently evil; however, the doctrines of orthodox Christianity were formalized and articulated against such claims.

As early church fathers formulated these official doctrines, their claims about Jesus Christ were closely intertwined with ideas about human nature. Judaism has always held human beings to be created imago Dei, in the image of God (Gen. 1:27), providing an explicit rationale for human dignity and the sacredness of human life (Gen. 9:6). New Testament writers such as St. Paul stated that Jesus Christ was the image of God (2 Cor. 4:4; Col. 1:15), and early Christians were quick to draw the connections between the two ideas. A common theme was that one of the purposes of the incarnation was to renew the imago Dei in human nature, and correlations between Christology and human nature were explicitly forged early on. Church fathers drew on body/soul anthropologies to grapple with the complexities of articulating the incarnation, and the idea that a human being is a union of body and soul was frequently used as an imperfect analogy with which to explicate the union of divine and human in Jesus Christ. In a strange circularity of ideas, this doctrine of Christ’s two natures, which had been explicated in part by appealing to dualist anthropology, was later used to reinforce this same anthropological framework. For example, Augustine (354-430) pointed to Jesus Christ’s two natures in order to affirm the soul-body harmony of the human person. This kind of argument demonstrates how intimately body and soul were understood to be connected to one another.

Although Christian thinkers drew on body/soul dualism to help clarify their understanding of Jesus Christ, their anthropological ideas also led to some very specific Christological difficulties. One of the big controversies was whether Christ had a human soul or whether he was just divine nature in a human body. Early ecumenical councils affirmed that to be fully human, Jesus Christ must have both a human body and a “rational soul,” in addition to a full divine nature. Similarly, the third Council of Constantinople (680-681) affirmed that Christ had a divine and a human will and a divine and a human “energy” (energeia).

Christians in the second through fifth centuries wrestled with the question of how and when souls were created—a difficulty that Greek philosophers had contended with previously. Some Christian thinkers (such as Origen) adopted the idea, common in Platonic thought, that souls are already pre-existent before conception. (The Pixar movie Soul provides a good contemporary depiction of this theory). This was often resisted, primarily because it was associated with Gnosticism and was, frankly, too dualistic for Christian sensibilities. Another theory, traducianism, held that the soul is inherited from one’s parents and generated naturally through biological processes. This theory was popular with early church fathers (such as Tertullian and Gregory of Nyssa), but as Neoplatonism gained in popularity among Christian thinkers, traducianism was looked on with increasing suspicion.

The earliest evidence of a third theory, creationism, dates to the beginning of the fourth century, in the writings of Lactantius (250-325). Innovating beyond existing Greek concepts, creationism credited God with directly creating and implanting individual souls within bodies. While this theory eased Neoplatonist concerns about organically produced souls, it created new theological problems. Many church fathers believed that sin (and thereby mortality) was an inherited quality; some went so far as to specify that it was passed down through the sexual relations that resulted in conception. (In this framework, the virgin birth of Christ was crucial to the belief that Christ was without sin.) While this theory of biologically inherited sin and mortality worked well with traducianism, it sat uneasily with creationism, which posited a divine origin of the soul without the aid of biological processes. Despite this inconsistency that could not be satisfactorily resolved, figures such as St. Jerome (c. 342-420) and Pope Leo I (c. 400-461) advanced creationism, and it became the dominant theory by the end of the fifth century.

In the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas and other prominent thinkers drew heavily on Aristotelian thought. For Aristotle, the soul informs the body as form does matter (hylomorphism). Medieval thinkers who adopted hylomorphism struggled with whether each body can be said to have a unique soul, rather than being informed by a universal soul. Although some, such as Aquinas, maintained that each person has a unique soul, there was lingering uncertainty amongst others as to how or if this could be adequately proved. Unlike the Platonic soul, Aristotle’s conception of the soul does not lend itself as readily to having a separable substance of its own. John Holdane argues that, for Aquinas, “a living human being is not a conjunction of two substances – body and soul – but a single unitary subject” (300). Caroline Walker Bynum affirms that “medieval people understood the self as a psychosomatic unity” and that “the specificity of person was understood to be carried not by soul but by body” (xvi). At the same time, we can see ways in which body and soul were sometimes divided conceptually in such a way as to legitimize horrific abuse of the body even while claiming the good of the soul. For example, the papal bull Romanus Pontifex (1454), one of the bulls that laid the foundation for the Doctrine of Discovery, expresses the hope that “the souls” of those enslaved “will be gained for Christ.”

With the advent of the Enlightenment, ideas about human nature shifted significantly. Many scholars have noted the “turn to the subject” that characterizes modernity, with Descartes as an obvious critical juncture in this movement. Jürgen Moltmann explains how old ideas about the soul were translated within this changing modern landscape: “Following the Christian tradition in its Augustinian form, Descartes no longer understands the soul as a higher substance: he sees it as the true subject, both in the human body and in the world of things. He translates the old body-soul dualism into the modern subject-object dichotomy” (250). Additionally, Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen notes that in Descartes’ sharpened dualism, “soul” becomes essentially equated with “mind”—the climax of a longstanding urge to link the human person’s “rational” capacities with the soul and with the imago Dei.

If Descartes and his peers began to understand the soul as the true subject in opposition to the world of objects (including the soul’s own body), soon enough the idea of a “soul” itself began to be questioned. Instead of a substantial, immaterial soul, philosophers began to think about personhood in terms of a “self.” English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) represents one of the major shifts in this direction. Yet for Locke, who retained his Christian faith even as many of his philosophical beliefs changed, this shift brought weighty ethical concerns along with it. Locke worried that without the concept of a substantial soul, it would be difficult to account for the continuity of personal identity across time, particularly across the dissolution and reassembling of matter that would need to take place in the resurrection. Without maintaining personal identity, individuals could not stand before the Judgment Throne of God after death and be held accountable for their actions in life. In light of these concerns, Locke began to consider new ways of assigning identity across time, such as consciousness and memory. Locke suggested that matter might be capable of thought, paving the way for other thinkers to consider that consciousness itself might be an emergent property of matter. (Although Locke’s suggestion sparked horror among many of his peers, it arguably holds similarities to the much older Christian tradition of traducianism.)

The problem of maintaining personal identity across time and change has proved to be a thorny philosophical issue, one of the major losses incurred by the absence of a substantial, immaterial soul. The last few centuries of Western thought have seen a flowering of theories of identity, with recognition of the significance of material conditions, other selves, linguistic communities, narratives, and so on, for the establishment of personal identity. Yet despite these significant shifts, the concept of an immaterial soul still lingers in odd places in popular consciousness and continues to carry weight in such conversations as the ethics of abortion or AI. In Christian theology, the concept of the soul still persists in many quarters, even though physicalist accounts of the human person are becoming more widely accepted. It remains to be seen whether Christian churches will incorporate these physicalist accounts doctrinally, or whether the idea of an immaterial soul will ultimately prove too bewitching.

Carolyn Mackie is a PhD candidate at the Toronto School of Theology, University of Toronto. She focuses her research on the connections between Christian theology of incarnation and philosophical anthropology in the writings of Søren Kierkegaard. She is a regular contributor at the Women in Theology blog.

Edited by Parker Cotton

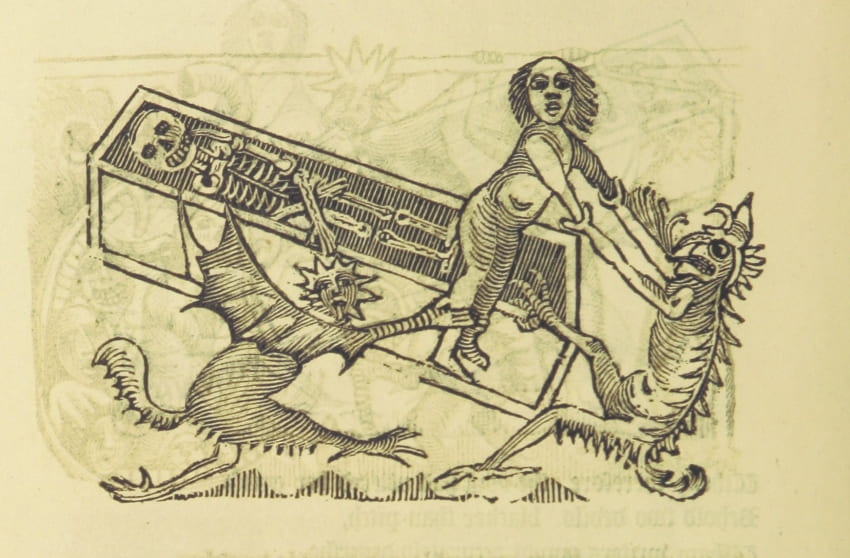

Featured Image: British Library digitised image from page 22 of “The Lamentable Vision of the Devoted Hermit (written of a sadly deceived soul and its body) [Translated by William Yates. With woodcuts.]”