By Alexander Collin

Michael Brinley is a PhD Candidate at the University of Pennsylvania working on twentieth-century Russian and Soviet History. His dissertation, titled “Model Cities and Mobilized Citizens: Contesting Soviet Urban Growth in the Era of Developed Socialism, 1957–1985” tracks the evolution of Soviet city planning institutions in the postwar decades during a period of industrialized mass housing construction, a period when Soviet city planners and architects were given a central role in the laboratory of social development during the last decades of rapid urbanization.

He spoke with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article, “Linguistic Diplomacy: Roman Jakobson between East and West, 1954–68” (volume 84, issue 2).

Alexander Collin: First, a little context, how does a historian of Soviet urbanism come to be interested in a migratory professor of linguistics? What led you to look so closely at Jakobson’s work?

Michael Brinley: I’ve gotten this question before; on the surface these topics may seem a little disconnected, but I came to them both through the same fascination with the legacies of the Soviet avant-garde from the 1910s. So, in that sense, Soviet urbanism and Jakobson are part of the same story. The biographies of individuals like Jakobson or Viktor Shklovsky or Mikhail Bakhtin involve dramatic reversals due to the exigencies of interwar and postwar politics, which give them this fascinating Zelig-like character.

There are more direct connections, too. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, Jakobson is in the same milieu as a number of the important figures in Soviet avant-garde history, Kazimir Malevich, Moisei Ginzburg, El Lissitsky. These are people he knew personally. So, the overlaps are personal and biographical, not just about intellectual connections or affiliation. On his return trips, he interacts with some members of those movements and there are a number of architects who are part of VKhuTeMas (Higher Art and Technical Studios), the Soviet Bauhaus, whom he knows personally.

This particular article came out of a research seminar on public intellectuals in the twentieth century. I was in comparative literature seminars on Soviet literature at the same time, and I realized that there was an opportunity to think more about Jakobson. As I had encountered him, he was very much understood as a linguist, as an important person in the genealogy of linguistics. But this had not been connected to his role as a Cold War public intellectual. When I dug a little deeper, it became obvious to me that those factors were central to his prominence in the American academy in the aftermath of the war.

Then there was a series of felicitous circumstances that made the project possible. I was writing this while based at the University of Pennsylvania, and Jakobson’s papers are scattered between Butler Library at Columbia and the MIT Archives, so those were accessible research trips for me. I was able to go and get into the archive and see what was going on at an institutional and biographical level in his later career.

AC: Are there parallels in the career trajectories of people in the architecture and urbanism space and Jakobson? Or do they diverge after that early period when they’re together in Moscow and St. Petersburg?

MB: Well, this kind of trajectory is certainly not unique to him. There’s an intellectual legacy of the avant-garde moving from the early days in pre-revolutionary Russia into Czechoslovakia in the interwar period and then making its way across the Atlantic as the Nazis make Europe more and more inhospitable.

But the story is so much more complex because the directionality is both ways. There are also people simultaneously moving into the Soviet Union. For example, one architect who’s famous for this is Vyacheslav Oltarzhevsky. He returns from the US to the Soviet Union in 1934, but like Jakobson he continues to straddle this transatlantic intellectual context in the interwar and postwar period.

Thinking more specifically about this paper, in the Cold War decades, intellectual exchanges are policy. I got very interested in the set of policymakers in the US government who established the terms for intellectual and professional exchanges and the way in which former residents of Eastern European countries think about how to use those programs. What is it that scholars think they’re doing when they go to the International Congress of Slavists versus how does someone like McGeorge Bundy or the State Department’s East-West Division think about that?

I discovered that there was quite a bit of interaction and conflict amongst Slavists in the United States about how to think about collaboration with the United States government over these exchange programs, attendance at conferences, et cetera.

AC: You say in the article that part of Jakobson’s diplomatic skillset is that he is different in different languages. Where do you see the most pronounced differences across languages: Does he express different ideas? Structure arguments differently? Work in a different tone or register?

MB: It’s said of Jakobson that he’s fluent in nine languages, and he speaks all of them with a Russian accent. In the article, I try to present a somewhat systematic assessment of how he presented himself in different languages. I wasn’t able to look at transcripts of his talks, but I was able to have a full list of all of the talks that he gave over the course of his trips back to state socialist countries.

It’s clear that he had three major categories of talks and that he would recycle them. He would reuse a talk on, say, the national poet of the place he was traveling to. So, if he was in Ukraine, he might focus on Shevchenko, for example, then if he gave that talk in Moscow, he would do something similar, but on Pushkin.

In some ways, that’s a foundational skill of comparative literary studies, but he’s also always pairing that with his commitment to the science of linguistics. And so, he almost always gives two talks at any conference that he attends, one that has something to do with literary studies and one that has something to do with the science of linguistics, and they’re always related to each other.

So, that’s a kind of subject matter difference. The language aspect is more difficult, I can tell you more about the English-Russian divide, but I don’t know the fine detail of what is different about the way he speaks in Czech or Polish.

AC: Jakobson’s interest in the natural sciences comes up a few times in the article, and the idea of linguistics as a science is a major theme with him. How important is his scientific project for his diplomatic project? What is the relationship between those two?

MB: I think that interest is grounded in his work with Nikolai Trubetzkoy on phonology. One could give a narrative about his scholarly life that builds from there and culminates in his publication of Child Language, Aphasia, and Phonological Universals.

That book is the result of a study done in Denmark, which he compiles into a monograph published in German in 1941, when he’s already fled Czechoslovakia and he’s posted at the University of Copenhagen for one year. He ends up fleeing further to Sweden and Norway, and then he gets on the last boat out of Norway in 1941. It’s clear that he’s quite aware of and proud of this kind of connection to the clinical sciences and he wants to keep a foot in that door.

For example, something I discuss in the paper is a 1965 UNESCO project entitled “International Study on the Main Trends of Research in the Sciences of Man.” Jakobson wrote the essay on linguistics. He leans heavily on the empirical natural sciences model when speaking to these multinational organizations. I make the argument that it is simultaneously a kind of good faith intellectual commitment, but also, very importantly, a way for him to keep many doors into many different scholarly fields open.

So, there is a personal and political component to his commitment to linguistics as an empirical science. And here Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyer’s work on clinical research in the interwar period was very helpful for me in understanding what the political stakes are, because I focus much more on the postwar period.

AC: Interesting, thank you! On page 356, you describe Jakobson as being, in some ways, paradigmatic of twentieth-century cosmopolitanism. What’s the paradigm? What does Jacobson tell us about it? What does it tell us about the period?

MB: There are two things I would accent here. One is the way that this is an identity that’s foisted upon him by the events of the twentieth century, and the other is a certain habitus that goes along with that experience.

There’s a particular type of internationalism that is a result of intense conflict, trauma, and warfare. This is why I start the paper with the episode of fleeing Prague twice. To be able to navigate those types of cross border interactions involves careful parsing of political circumstances; these are not borders that everyone gets to cross. It’s trauma, but at the same time, he is part of the “jet set” of the mid-twentieth century.

Jakobson is also paradigmatic of a kind of habitus, a way of life, that is quite distinctive. I was struck that when Jakobson arrives in New York in the early 1940s, he seems to be integrated very quickly into familiar Jewish-American locales. So, for example, he spends many of his summers in Hunter in the Catskills, in what’s known as the “Borscht Belt.” It was amusing to think of Jakobson laughing at a Mel Brooks or Lenny Bruce routine while planning the next International Congress of Slavists in Moscow.

AC: Do we know if Jakobson goes to those stand-up comedy shows while he’s holidaying in the Borscht Belt? Are there documents on what he thought of them?

MB: I would have to assume he did. I looked for something in his correspondence that would confirm it, but there was no specific instance of him talking about it. But he was there in the summers all the time, starting in the late 1940s through the middle of the 60s. It is another one of these Zelig-like things where his life connects with cultural or political developments in ways you wouldn’t expect. Another example would be when he’s in Prague in August of 1968. There are so many people there that are surprising: the day before the invasion, The Moody Blues are playing a televised show on the Charles Bridge; Shirley Temple Black is in Prague that day; Robert Vaughn, “the Man from U.N.C.L.E.” is shooting a Hollywood movie and makes up an absurd story about rescuing a Czech woman named Pepsi Watson; of course, Jakobson is there too.

AC: On page 335, you say that “the pretense of being apolitical was an important precondition for Jakobson’s diplomatic work.” Do you mean just Jakobson’s pretense, or is that a broader claim about the possibilities of apolitical action in these circumstances?

MB: In the context of this article, I think it’s a question of Jakobson learning to appear apolitical. When Jakobson comes to the United States, he has a fairly tumultuous first decade institutionally. He has this chair at Columbia that receives a grant from the Czechoslovakian government. But then, there’s a coup d’état in February 1948 and the Communist Party begins purging the opposition.

That leads to a McCarthyist moment in the US, and Jakobson is very much caught up in that and threatened by it. So, he learns in the process. In 1948–49, Jakobson comes under fire, but he’s protected. There are a couple of very important people who help him. One is Dwight Eisenhower, who was serving as university president for a spell, seemingly to pad his resume for a presidential run in 1952. The other is a vice president at J.P. Morgan, a guy named R. Gordon Wasson. Henryk Baran has written some articles about Wasson and Jakobson, contextualizing their relationship.

The long and short of it is that Wasson is married to a Russian émigré Valentina Pavlovna, and they become fascinated with the cultural history of mushrooms. They write a history of mycophilic and mycophobic societies. He’s actually an important popularizer of psilocybin magic mushrooms in the United States in the 1950s and has connections to the CIA’s MK-Ultra program. He goes down to Mexico, participates in some of these rituals, and then writes a photo-essay for Life magazine introducing “magic mushrooms” to a popular audience.

Valentina Pavlovna seems to have known Jakobson from childhood and the book on mushrooms is dedicated to him. He consulted on the philological work for the book. Wasson provides funding for Jakobson’s trips in conjunction with the Ford Foundation, so Wasson is an important figure there. There’s a political dimension too: it’s important for Jakobson to have a kind of cover and he is not afraid to use that cover. That creates a lot of animosity between him and other representatives of the émigré community in the American Academy, which is something I try to tease out a little bit in the paper.

AC: To close, I’d like to talk about citizenship, which I know is also a topic you’re interested in. What does Jacobson’s life, and in particular the diplomatic life, tell us about citizenship in this period?

MB: Yeah, it’s a good question, it’s suggestive. I think the malleability of identity is really important. These citizen identities are flexible, even in terms of their legal definitions. A lot of what Jakobson does might be categorized as furtive diplomacy, secret state funding for diplomatically consequential travel and exchange. A less generous take might call it espionage work.

He acquires US citizenship in the late 40s, but in the course of his life he has Russian Imperial and Czech citizenship and even a Soviet passport for a brief spell. So, he has all these different citizenships over the course of his life. And I think that might tell us something about the construction of a sort of postwar American civic identity and the various uses that it can be put to—the communicative events that it can precipitate.

Like many Russia experts in the American Academy, he has a heritage in those places, but thinks of himself as sort of from nowhere, or better, from everywhere. Many of the people that he’s most intent on resisting are the integral nationalists. Those are the scholars that he’s least interested in cooperating with or having anything to do with. He reserves his most vitriolic speech for them and their “noxious parochialisms.”

In that way, he occupies a particular position on the spectrum that exists in the emigrant community. Among these people who fled revolution and who fled war, but who might have fled for very different reasons. In the context of the Slavic émigré community in the United States, Jakobson represents one of the more tolerant figures towards the Soviet Union. Jakobson’s late career is a unique cipher, a way to see what that spectrum looked like and then how it has had significant repercussions for American politics in the Cold War period as well.

AC: So, last question, what are you working on now? What are you working on next? Are there any other publications or appearances coming up?

MB: Right now I’m working furiously to finish a dissertation and defend it this summer. So that’s the top-bill item. I have a piece that may be coming out later this year in an edited volume on design institutes in the socialist world.

And I have an article that I’m working on about the city plan in the 1970s. It is about how the city plan became an object around which urban residents and citizens could mobilize to articulate claims on the state. In particular, it is about how master plans could represent the lobbying of various interest groups within city government in late-Soviet politics; acting as something like a political machine that was not necessarily dominated by the factory or party bosses.

Alexander Collin is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam where he works on northern Europe from the 1490s to the 1700s. His doctoral thesis aims to test the historical applicability of theories of decision making from economics and organizational studies, considering to what extent we should historicize the idea of ‘The Decision’ and to what extent it is a human universal. The project has been funded by the Leverhulme Trust and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst. Alexander has written for The Historian magazine, Shells and Pebbles, The History of Knowledge Blog, as well as academic publications. Alongside his historical work, he also contributes reports to the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. He studied at King’s College London, Humboldt University Berlin, the University of Cambridge, and Viadrina University Frankfurt.

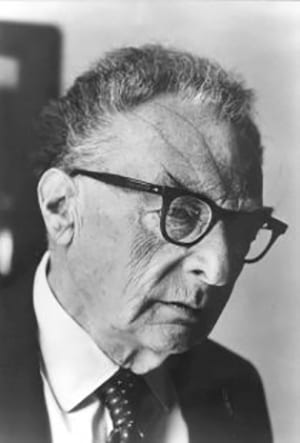

Featured image: Roman Jakobson, Wikimedia Commons user Raulelgreco, CC BY-SA 4.0.