By Theresa Müller

From 1992 until 1994, Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña staged the performance art piece titled The Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West, in multiple venues around the world. While both artists are known for exploring issues such as race, identity, and power, that particular performance strived to challenge the dominant narratives towards indigenous cultures. The artists consciously chose venues in countries possessing a history of colonial exploitation and eradication of Indigenous peoples: such as the United States, England, Spain, and Australia. With their ironic commentary on colonial narratives and practices, the artists processed and raised attention towards the atrocities of the Western world during the colonial period. Importantly, the performance confirmed many of the fundamental claims of postcolonial studies and displayed how their theory translated into practice.

In The Couple in the Cage, Fusco and Gómez-Peña performed as “undiscovered Amerindians” from a previously unknown island. During the performance, the artists locked themselves into a golden cage. They exaggerated Western stereotypes of indigenous peoples and communicated with the audience through a tour guide who translated for them and took photographs of the scene. This interaction and the performances were filmed and later published as a documentary directed by Coco Fusco and Paula Heredia.

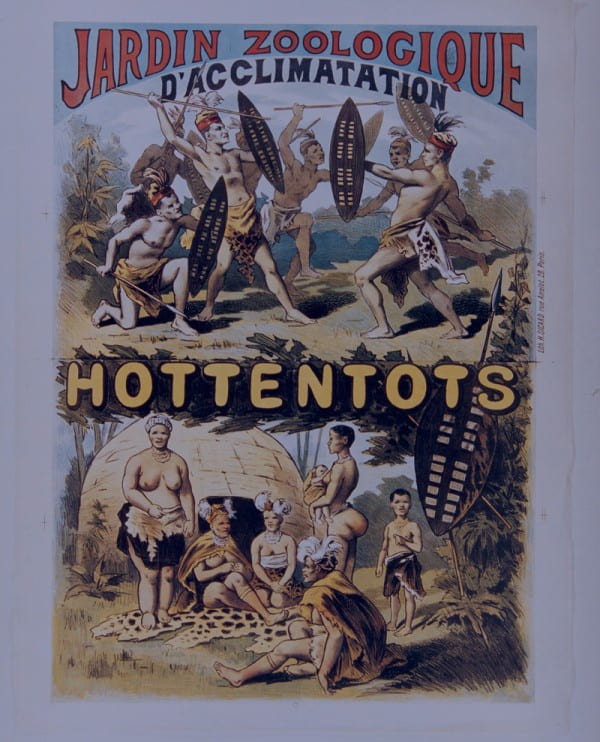

Human exhibitions, where non-white ethnic groups were abducted from their homelands and exhibited in zoos, were a common sight in Europe from the 1850s until the 1960s. The creators of the modern zoo, such as Carl Hagenbeck and P.T. Barnum, believed that these living ethnic exhibitions had great social, cultural, and humanitarian significance. Over time, human exhibitions became a lucrative business, as capturing and deporting humans proved more profitable than importing animals. The documentary by Fusco and Heredia juxtaposes The Couple in the Cage with actual footage of human exhibitions from the early and mid-20th century. By doing so, the artists displayed how human zoos dehumanized non-white ethnic groups, justified the prevailing racial hierarchies, and promulgated the belief in Western civilizational superiority. Human exhibitions served the colonizers to assert dominance in the form of body control and exploitation.

Artists of color often perceive the body as a symbol of colonial violence that affects the lives of people who are not perceived as white. Consequently, postcolonial art and literature center their attention on the body as it represents the historical exercise of power. This is true for political systems that implement policies that either restrict or liberate the body according to their order of priority (e.g., the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 in the United States). Postcolonial artists use performance art to bring attention to non-white bodies and consciously subvert metropolitan cultural norms. Importantly, in contrast to other art forms, performance art allows artists to reenact past social situations and mechanisms of control.

The Couple in the Cage was originally meant to be an ironic comment on colonialist practices of the past. However, the artists exceeded their original goal: they exposed the deep continuities of Western audiences’ racism towards people of color. The comparison of the performance art piece’s audience and historical footage revealed how the reactions of contemporary Western audiences mirrored those of the actual human exhibitions of the past. Through the display of their bodies, Fusco and Gómez-Peña ironically enacted the relationship between stereotypes and the colonizer’s perceptions of indigenous cultures: for example, with their clothes. Fusco and Gómez-Peña quickly noticed that the audience really believed they were a newly discovered tribe of Native Amerindians. As a result, capturing the reaction of the audience for the documentary became the primary goal of the artist couple.

To this end, Fusco and Gómez-Peña applied some aspects of exhibition strategies to emphasize the racist character of human zoos. The artists’ selection of locations mirrored the concept of human exhibitions: it involved separating both groups and placing them in separate spaces where direct interaction was impossible—just like how it was done in zoos. Their performances displayed how the physical separation between the Western audience and the exhibited “savages” dehumanized people of color. Yet Fusco and Gómez-Peña went even further and chose “institutionalized places of history”—such as museums and galleries—as the setting for their performance. By choosing museums as the setting of their performance, Fusco and Gómez-Peña criticized institutions that appropriate artefacts and display them outside their cultural contexts, thus counteracting their intention of preserving history. The documentary highlights the misplacement of certain exhibited items in these institutions, as many of them were stolen by Western colonialists.

An important part of the performance was the tour guide. The guide served as an intermediary between the artists and the audience: his role was to answer the visitors’ questions and pretend to translate the couple’s made-up language. Hence, the guide emphasized the physical and cultural distance between the artists and their audience. While the performance conceptualized the couple as exotic Others who cannot speak for themselves, the Western tour guide exercised power over the situation by supervising ethnological expositions and controlling the interaction between the “savages” and the audience. The couple’s inability to be understood due to their made-up language served as a reminder of the voicelessness experienced by the oppressed Other. Thus, the performance confirmed the famous observation of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak that the Subaltern cannot speak. Those who lack a voice and are not comprehensible are at the lowest position within the social and racial hierarchy. By translating for the artist couple, the white tour guide was not empowering them: they reinforced the imbalance of power, which symbolically hindered the representation and agency of the colonized and silenced non-Western voices.

The performance art piece not only tried to recreate the colonizer’s exhibition strategies but also served as a vehicle for further reiterating the theories of postcolonial studies. Importantly, the reactions of the audience to the “savage” couple mirrored those of the visitors to human exhibitions. In the position of the voyeur, both visitors of the human exhibitions and the audience of the performance art found themselves in a place of power. Postcolonial scholars such as Homi Bhabha have noted that the West exerts and maintains power by controlling the narrative of how non-white bodies are perceived by separating the colonized from the colonizers. The colonial gaze is based on the way perception is constructed, and shaped by cultural norms, social beliefs, historical narratives, and power dynamics. Voyeurism corresponds with the natural desire of watching, but the gaze of the active part (the audience of the performance) creates a power imbalance. Consequently, the audience no longer sees the couple as people but as objects.

The documentary emphasizes this perspective when showing how the audience talked about the artists. The audience’s discussion about the couple’s behavior reflected how one would analyze an object exhibited in a museum. For instance, one viewer reiterated his thoughts on the couple’s fascination with technical devices by saying: “The fact that he [Gomez-Peña] is so interested in things that he doesn’t appear to understand.” Thereby, he reduced Gomez-Peña to a subject of study, reinforcing the notion that the colonized are passive while the colonizer still maintains control. As the postcolonial theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha aptly notices, the representation of the Other through the eyes of the colonizer reduces them to a passive object. However, Fusco achieved that effect on purpose: by capturing the performance and the reaction of the audience on camera, she redirected the gaze from the couple in the Cage towards the viewers. It is the audience’s reaction that becomes the actual desired outcome. By turning around the gaze from the viewer to the ones being viewed, the audience of the performance is being watched and judged for their reactions by the viewer of the documentary. Therefore, the documentary turned the voyeuristic gazes towards the audience of the performance, revealing their lack of power and agency. The artists become an active part of the performance despite being in the cage.

Homi Bhabha points out that the colonial gaze produces ambivalence in the relationship between the colonizers and the colonized, resulting in an unstable identity. During the performance, it can be observed that the audience reacts to the non-white body in a dichotomous way, which confirms the claim of Bhabha. On the one hand, the artists are perceived as dangerous and wild members of an uncivilized Amerindian tribe. On the other, their bodies are exoticized and looked at with deep fascination. In both cases, the colonized body is subject to the objectification and judgement of the white audience’s gaze. This objectification can be observed when the guide demands payment from the audience so that the “indigenous” people dance or tell stories. The documentary shows how the audience gets pictures taken with the couple, laughing and posing in front of them. Yet, the documentary also filmed people who were genuinely scared of the supposedly “wild” couple. For example, one child was filmed screaming: “Careful! He is going to eat your suit!” hence continuing the ongoing practice of non-white bodies likely being treated as “savages.” Their observation showed the ongoing importance of how the hegemonic white system treats non-white bodies.

Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s performance exhibits the deep continuities of colonial and racist modes of thinking in Western societies. Their exhibition was a powerful criticism of the notion of a post-racial society, as it emerged in the public discourse by the 1990s. According to the sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, the notion of “colorblindness” – the belief that a person’s race or ethnicity does not determine their treatment by their environment – is a more subtle form of racism, which explains racial inequalities by other factors such as work ethic, and market dynamics. Contesting this notion, Fusco and Gomez-Peña showed that their bodies were still perceived and treated as colonial objects. More importantly, the performance art of Fusco and Gómez-Peña verified in practice many of the key arguments of postcolonial theory. As a result, the documentary can still inspire contemporary viewers to critically reflect on their assumptions about Indigenous cultures and behaviors towards non-white bodies.

In conclusion, The Couple in the Cage constituted a powerful political statement about the treatment of non-white bodies in the contemporary West. Through their art, Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña uncovered the strategies of dehumanization, problematized voyeurism, and criticized the narrative of an alleged post-racial society that emerged in the 1990s public discourse. Their performance proves that the process of decolonization is still ongoing. There is much work ahead for breaking down the power imbalance between the “Western” and “non-Western” worlds.

Theresa Müller is a master’s student of North American Studies at the University of Cologne. She is interested in art. Her research interests include Gender Studies and the influences of the 19th century on society.

Edited by Maria Wiegel and Artur Banaszewski

Featured image: Poster for Hottentot’s at the Jardin d’Acclimatation at Paris, around 1877. Courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.