By Nilab Saeedi

Muslih al-Din Lārî (d. 979 AH/1572 CE) was a historian on the move. During his lifetime, he traversed and lived in all the “Three Gunpowder Empires” – the Mughal, Safavid, and Ottoman Empires. As a polymath of extraordinary versatility, Lārî’s intellectual pursuits ranged from poetry and commentary to mathematics and astronomy, establishing him as a prominent figure in the intellectual milieu of the 16th-century Islamic world.

Lārî excelled in speculative sciences (ulûm-ı akliye) and practical sciences (ulûm-ı nakliyeye)—such as fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence), tefsir (Quranic Exegesis), and hadith (Prophetic Tradition)—as well as in various other scientific fields. He wrote poetry in both Arabic and Persian, and produced numerous works of history, most of them being commentaries on other Islamic authors’ writings. Through Lārî and his writings, we gain insight into key debates regarding politics and the intellectual life of the 16th century Islamic world.

Lārî’s best-known work was Mir’atü’l-advâr ve Mirkâtü’l-Ahbâr (The Mirror of Periods and The Staircases of News): a world history written in Persian encompassing the history of humankind from the first human being, Adam, to the enthronement of Sultan Selim II in 1566. Comprising 10 chapters, the book was dedicated to Selim II, as Lārî sought his patronage. Importantly, Mir’at al-advar underwent significant revisions and expansion at the hands of a well-known Ottoman historian of the period, Hoca Sa’deddin (d. 1599), who, on the demand of the Grand Vizier Sokullu Mehmed Pasha (d.1579), translated it into Ottoman Turkish. Lārî’s book holds a noteworthy status in Ottoman world historiography, and its popularity among the Ottoman elite is evident from the surviving number of manuscripts.

Lārî was a critical historian, an example of which can rarely be found among Muslim historians in the early modern period. His approach was distinguished by an extensive yet conscious use of diverse sources and narratives. For instance, when recounting Persian legends and the stories of the first prophets like Adam, Noah, and Abraham, he did not refrain from subjecting them to thorough criticism.

Lārî’s book offers a unique perspective on the intellectual climate of his time, shedding light on the interrelation of politics with theology and displaying the significance the Ottoman elite attributed to historical knowledge. In this article, I intend to examine how the respective works of Muslih al-Din Lārî conceptualized history and how he defined the vocation of a historian.

Lārî commences Mir’atü’l-advâr with a heartfelt expression of gratitude to God. From the opening lines of his book, he acknowledges that God bestows historians with the gift of knowledge and reason, and that the pious will always recognize God’s presence in their historical accounts. Lārî stresses that historians who recognize the oneness of God and maintain unwavering faith will receive divine aid and guidance in their work. His emphasis on piety and religion shapes his conception of history: only a historian who is true to their faith can be true to their scholarship.

For Lārî, history is more than a mere chronicle of events; it serves as a means of understanding the society we inhabit and our place within it. He suggests that the pursuit of scholarship and the pursuit of faith need not be mutually exclusive but should coexist harmoniously. According to Lārî, only a historian who recognizes this interconnection is capable of understanding and interpreting the past.

The introduction to the Mir’atü’l-advâr includes an important poem encapsulating his vision of history as a field of study. According to Lārî, history is a discipline that serves as a reminder of God and its divine powers.

This is the way that every historian knows it:

That He was, and that there was no trace of anyone.

This is how obvious the Lord of meanings is:

He is eternal, while all else is transitory.

Lārî views history as a study of the past with the purpose of applying its lessons in the future. He sees history as knowledge (‘ilm) to be used for future endeavors, with a particular focus on its implications for those in positions of power. Understanding history is important as it empowers individuals to learn from past events, enabling them to make informed decisions and avoid repeating past mistakes.

At the same time, Lārī emphasizes that all events unfold in accordance with divine will, implying that history mirrors God’s will and intentions. A truly wise and knowledgeable historian should have a profound comprehension of the nature of existence and the role that God plays in shaping the course of the world’s destiny. As all things are transient, only God remains eternal. Therefore, Lārî’s assumes that faith and the pursuit of knowledge are inseparable: the pursuit of wisdom should be guided by faith, while faith should be enriched by the pursuit of knowledge. This combination enables the historian to gain clearer insights and a deeper understanding of past events.

Lārī believes that history constitutes a reservoir of knowledge about the past, valuable for its potential to inform and improve the future. His book focuses on preserving the accomplishments of individuals who have made noteworthy contributions to various fields of knowledge and the arts. Consequently, he views the study of history as a means of remembering those who have preceded us and ensuring that their legacy is not forgotten. By documenting their achievements, we can ensure that their wisdom is passed on to future generations. Lārî sees history as a bridge between the past and the present, connecting us to the knowledge of our ancestors and guiding us toward a more promising future.

The idea that human knowledge has boundaries is firmly established in Islamic scholarship. According to Islamic theology, while human beings possess the ability to acquire knowledge and understand the world, there are inherent limitations to our intellectual capacities. Consequently, Islamic scholars have developed a discipline known as ‘ilm al-kalam (Arab. The Science of Islamic Theology), which explores the limits of human reason in understanding nature and the universe. Islamic theology acknowledges the significance of the human intellect in understanding God’s creation but recognizes that knowledge is always incomplete and fallible. While Lārî accepted this assumption, the conclusions he derived from it differed from those of his contemporaneous scholars.

According to Lārî, only a historian who recognizes the limits of knowledge can appreciate the transience of human existence. Lārî was convinced that all aspects of life—be it individuals, societies, and civilizations—have a beginning and an end. Only God, as the ultimate source of existence, transcends these limitations, being the sole eternal being. Thus, Lārî was convinced that past events reflect God’s will: with human actions having an impact, but the course of history ultimately determined by a Supreme Power. Recognizing the transience of human existence is a necessary attribute of a wise and knowledgeable historian, who should approach their work with humility and reverence. However, Lārî does not conclude that historians should abstain from studying the actions of individuals and communities. Instead, he believes historians should be aware of the larger forces at work in the world. This perspective encourages the historian to focus on the bigger picture and not become entangled in the minutiae of human history.

Lārî stresses the importance of studying history, claiming that its existence stretches back to the beginning of time. Therefore, the study of history is not merely a human endeavor: God Himself reminds the Prophet Muhammad of past events, underlining the divine significance of historical control over the destiny of life. Lārî asserts that individuals who pursue truth and demonstrate wisdom are the most content in both their worldly and eternal lives. The people who study history gain valuable insights into past actions and their outcomes, enabling them to make conscious choices between positive and negative choices. Thus, Lārî argues that history is a propaedeutic knowledge—a discipline that equips individuals to learn from the past and make wise choices about the present and the future.

Lārî explains the paramount importance of knowledge and learning by quoting a Qur’anic verse that states: “So ask those who know, if you don’t know.” This reference underlines the crucial role of scholars in disseminating information and facilitating the acquisition of knowledge. According to Lārî, a historian’s defining characteristic is their ability to preserve the virtues and attributes of significant individuals throughout history. Historical accounts enable people to learn about the lives of great individuals, their virtues and vices, and the impact they had on their society and the world. By chronicling these figures, historians ensure that their names and achievements are commemorated to educate and guide future generations. Lārî further asserts that this emphasis on preserving knowledge is vital for good governance, and he emphasizes the pivotal role of historians in documenting and providing insight into the past. Thus, the expertise and knowledge of historians are indispensable to political leaders in their decision-making process.

Throughout Mir’atü’l-advâr, Lārî emphasizes the importance of historical awareness for monarchs and rulers. In his view, knowledge of the past allows rulers to draw lessons from history and improve their future decisions and policies. For this reason, he explicitly states that the intended audience for his book is high-ranking individuals, such as sultans and monarchs. Lārî’s use of specialized language and writing style reflects his belief that historical knowledge is the exclusive domain of the educated elite, who are best equipped to understand and utilize its insights. His book was intended to advise and instruct the Ottoman political elite.

Lārî’s emphasis on the importance of historical awareness for those in power reflects the broader belief in Islamic theology that history is a potent tool for the ethical and political guidance of society. This perspective stems from the belief that history provides lessons and examples to guide moral and political behaviors. Consequently, Lārî perceives the study of history as an essential component of the education of those who aspire to positions of power and influence. Equipped with historical awareness, they are better positioned to make informed decisions and develop strategies for the future governance of their state. The political elite must possess a comprehensive understanding of the past to remain vigilant in the face of dangers and challenges.

Lārî believed that historical awareness was critical to the survival and prosperity of a state. However, in this perspective, knowledge of history was not for everyone. He perceived history as belonging solely to an elite class of people entrusted with the ethical and political guidance of society. His book viewed history as an archive of learning through which societies could review past experiences and make present and future choices. Nevertheless, only high officials and those in positions of power would be making these choices, making history, as Lārî understood it, reserved for the elite.

Lārî’s focus on appealing to leaders and rulers highlights the value of patronage in the intellectual and literary life of the Ottoman Empire. After all, it was no coincidence that he dedicated his book to Sultan Selim II. When Hoca Sa’deddin translated Mir’atü’l-advâr into Ottoman Turkish, the work received high praise from the Ottoman political elite. According to Turkish historian Baki Tezcan, Hoca Sa’deddin’s career as both a historian and a prominent figure in Ottoman politics was initiated through this translation, after he was appointed as the tutor of Prince Murad (later Murad III) in 1573. Despite Lārî having passed away before his book gained widespread popularity, the intellectual legacy of his work endured long after his passing.

Lārî’s book played a vital role in shaping historical understanding within the sixteenth-century Ottoman Empire. Mir’atü’l-advâr stands out as a remarkable work of world history, distinguished by its original insights into the significance of historical awareness for theology, politics, and society. Lārî’s sophisticated grasp of the complexities involved in writing history renders Mir’atü’l-advâr a monument to the advancement and depth of early modern Islamic historiography. Many of his arguments can still be used in contemporary discussions concerning the role of history in our understanding of the world around us.

Nilab Saeedi is a Ph.D. student in history at İbn Haldun University in Istanbul, Turkey. She also holds a research fellowship position at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Her research interests encompass early modern Ottoman history, the intellectual heritage of Islamic scholars, and manuscript study. Fluent in several languages, including Turkish, English, Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Persian, Uzbek, Hindi, and Urdu.

Edited by Artur Banaszewski

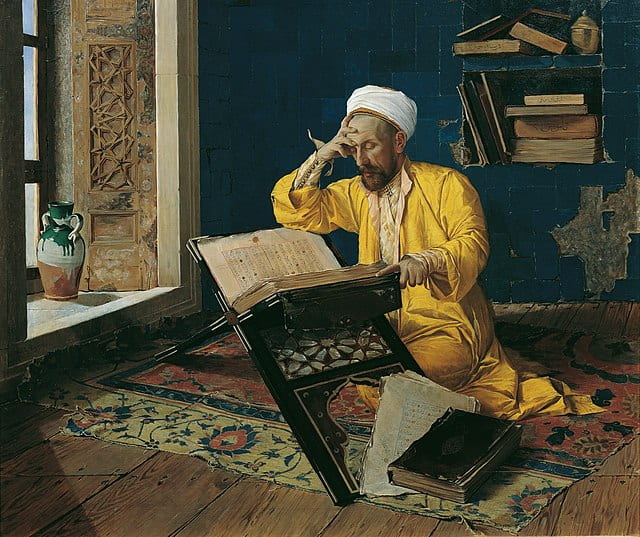

Featured Image: Osman Hamdi Bey, Islamic theologian with Koran, 1902. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.