By Addis Goldman

Eric Helleiner has long been recognized for his foundational contributions to international political economy and studies in global governance. A professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo, Helleiner’s recent books include The Forgotten Foundations of Bretton Woods: International Development and the Making of the Postwar Order (Cornell, 2014) and The Status Quo Crisis: Global Financial Governance After the 2008 Meltdown (Oxford, 2014), along with co-authored books such as The Great Wall of Money: Politics and Power in China’s International Monetary Relations (Cornell, 2014). In addition, he has published over 100 journal articles and book chapters and is presently co-editor of the book series Cornell Studies in Money.

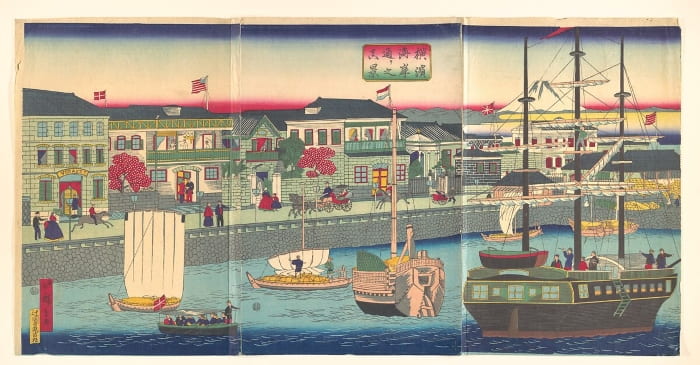

Addis Goldman spoke to Prof. Helleiner about The Neomercantilists: A Global Intellectual History (Cornell, 2021), which, as Helleiner explains, was necessary to write before publishing his latest book, The Contested World Economy: The Deep and Global Roots of International Political Economy (Cambridge, 2023). Although both texts are deeply topically relevant, The Neomercantilists is particularly so. After decades marked by the deepening and dissemination of globalization, recent years have seen the revival of strategic protectionism and the intensification of geoeconomic and geopolitical competition. Although mercantilist ideas about the primacy of exports and the accumulation of state wealth, promoted by figures such as Jean-Baptiste Colbert, have influenced statecraft since the early-modern period, neomercantilism, as Helleiner argues, is a distinct concept worthy of its prefix.

***

Addis Goldman: The Neomercantilists addresses a fundamental shortcoming in the intellectual history of international political economy. In the Introduction, you suggest that the ideological atmosphere of the Cold War era effectively marginalized interest in the history of neomercantilism, even within the field of IPE, which has recognized this perspective as part of its canon since the 1970s. Can you talk about some of the initial scholarly motivations for writing this book?

Eric Helleiner: The Neomercantilists was not a book that I planned to write. Beginning around 2015, I set out instead to write a history of the deep roots of the field of international political economy (IPE) in the pre-1945 era. The scholars who pioneered the modern field of IPE in the 1970s — people such as Susan Strange and Robert Gilpin — saw themselves as reviving an earlier pre-1945 tradition of political economy that had analyzed international and global issues. They usually invoked earlier thinkers from the three intellectual perspectives of economic liberalism (e.g., Adam Smith, David Ricardo), neomercantilism (e.g., Alexander Hamilton, Friedrich List), and Marxism (Karl Marx and the later Marxist theorists of imperialism such as Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg). IPE textbooks today continue to cite these deep roots of the field, but no book existed to provide students with a more comprehensive overview of pre-1945 debates about the politics of the world economy. My goal was to fill this gap in the curriculum.

It quickly became evident to me, however, that the history of neomercantilism was the least studied of the three pre-1945 perspectives that were referenced in IPE textbooks. As I delved into this history in more depth, it also became clear that the textbook focus on Hamilton and List was much too narrow, particularly if one embraced a more global perspective. I began to realize that I could not write the broader history of IPE’s deep roots without first writing a book that challenged the conventional understanding of the history of neomercantilist thought in my field. The Neomercantilists was the result. With that completed, I was able to return to the main project which was published earlier this year: The Contested World Economy: The Deep and Global Roots of International Political Economy. The latter has two short chapters on neomercantilist thought, which I could not have presented succinctly without writing the earlier book.

AG: The global reception of Adam Smith’s ideas around the turn of the nineteenth century is decisive for your understanding of neomercantilism and neomercantilists, who are, roughly speaking, “post-1776 thinkers” responding to the “new liberal economic ideology that became increasingly prominent in the wake of the publication of The Wealth of Nations (1776)” (5). To what degree were early neomercantilists such as Alexander Hamilton, a key theorist of the “American System,” responding to the concrete geoeconomic consequences, rather than the ideological content, of Smithian free trade liberalism (and an associated kind of Kantian perpetual peace teleology)?

EH: As you note, I argue that “neomercantilists” were distinguished from earlier “mercantilists” because they were responding to liberal ideas of free trade and free markets that became increasingly prominent after Smith’s 1776 book. Hamilton was one of the first prominent thinkers to do this in a sophisticated way. Although he was familiar with European mercantilist ideas, he went beyond them through his careful engagement with Smithian arguments in his famous 1791 Report on Manufactures. But it is certainly true that he and other neomercantilists were also often responding to the concrete circumstances in which they found themselves, including geopolitical ones.

Indeed, geopolitics loomed large for neomercantilist thinkers. They were focused on promoting not just the wealth of their state but also its power, and they saw the two as intricately connected. They believed that state wealth and power could be cultivated with strategic trade protectionism and other forms of government economic activism, and most were focused on using these policies to promote industrialization, which they saw as critically important for state power. All of these arguments could be found in Hamilton’s report, which also invoked the geopolitical vulnerability experienced by his country in its recent revolutionary war because of its lack of domestic manufacturing capacity. As he put it, “extreme embarrassments of the United States during the late War, from an incapacity of supplying themselves, are still a matter of keen recollection” (37). Like Hamilton, many early neomercantilists also came from places that were threatened by British military power. They often saw that power as underpinned by Britain’s growing industrial might. Many also saw British advocacy of free trade abroad as an effort to consolidate its geopolitical dominance by curtailing other countries’ industrialization and locking them into a subordinate role of commodity exporting. That case was made, for example, by followers of Hamilton, such as Mathew Carey who became a prominent advocate of what Henry Clay referred to in 1824 as the “American System” of protectionism. The same line of argument also featured prominently in the most famous neomercantilist text in the first half of the nineteenth century, Friedrich List’s 1841 The National System of Political Economy, whose content was partly shaped by List’s encounters with Carey and other American protectionists in the 1820s.

Because of the title of List’s book, I should also add, as a definitional point, that neomercantilists are sometimes referred to as “economic nationalists.” The label is understandable in the sense that many of them – including List – hoped to make the economy serve nationalist goals. But I steer away from this term in the book for two reasons. First, nationalism can be associated with the advocacy of many other kinds of economic policies, including liberal ones. In other words, not all economic nationalists are neomercantilists. Second, not all neomercantilists are economic nationalists in the sense that some of the ones that I analyzed did not embrace nationalist worldviews. They sought to promote the wealth and power of states that were not conceptualized nation-states, such as empires or sub-imperial states.

AG: The German political economist Friedrich List (1789-1846) looms very large in the book. The title of Chapter 2 is “Friedrich List’s Idiosyncratic Synthesis.” Why “idiosyncratic”? You note that his views of free trade began to change because of “concerns about how the restoration of open trade after Napoleon’s downfall allowed British manufacturing exports to undermine German industry” (45). He produced neomercantilist articles of faith like, “The power of producing wealth is … infinitely more important than wealth itself” (56). He was active on the American scene in the early to mid-nineteenth century. He decried “the cosmopolitical doctrine of Adam Smith,” although he was a political liberal. Why is List so foundational for any account of neomercantilism?

EH: For most IPE scholars today, List’s 1841 book The National System of Political Economy is the most important neomercantilist work in the pre-1945 years. Particularly well-known is a passage in which he criticized British free traders of hypocrisy for discouraging other countries from pursuing protectionist policies that he believed had built up Britain’s wealth and power in the past. As he put it, “It is a very common device that when anyone has attained the summit of greatness, he kicks away the ladder by which he has climbed up, in order to deprive others of the means of climbing up after him” (295). The phrase “kicking away the ladder” is even the title of a best-selling book on political economy by Ha-Joon Chang.

Building on the work of other historians, I highlight how List’s work synthesized the ideas of many earlier thinkers that he encountered, including those in the United States and France, where he lived for some time. I describe this as an idiosyncratic synthesis because List drew on other people’s ideas in various selective ways while also adding some distinctive twists of his own. The latter included some ideas that were rarely repeated by later neomercantilist thinkers who invoked his work. One example is List’s view that countries in the “tropics” were not suited for industrialization and should remain commodity exporters under conditions of free trade or colonial rule (of which he strongly approved). Another was his view that neomercantilist policies should be seen simply as a temporary strategy to build greater equality among (temperate zone) nations which could then unite in a future “universal republic.”

AG: Chapter 3 is subtitled “The Listian Intellectual World,” while Chapter 4 is titled “List-Inspired Neomercantilism Beyond the Nation-State.” Clearly, List was very influential, but you emphasize that his influence manifested in a variety of divergent political-economic programs. In these chapters, we encounter figures like the German intellectual Gustav Schmoller and the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gökalp, both of whom were interested in a “social version of neomercantilism” (81). The Japanese finance minister Matsukata Masayoshi, who in the 1880s pursued forms of “financial neomercantilism” is also important, as is Mahadev Govind Ranade, the Indian nationalist who, in the late nineteenth century, espoused a “neomercantilism of the colonized” (89, 109). We also encounter Alfredo Rocco, the Mussolini loyalist who advocated “national syndicalism” (101), as well as the British tariff reformers who, at the turn of the twentieth century, conceived of neomercantilist policies in the context of empire. What should we understand about some of these figures and their various Listian-inspired positions?

EH: At the most general level, I think it is important to recognize the extensive international diffusion of List’s neomercantilist ideas. Much ink has been spilled about the global spread of liberal and Marxist ideas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but less attention has been paid to the international circulation of neomercantilist thought. This relative neglect may reflect the fact that there was no institutional equivalent to the liberal Cobden club or the Marxist Comintern to promote this ideology transnationally. But the ideas of List and other neomercantilists (particularly Henry Carey, son of the Mathew Carey I mentioned earlier) did circulate widely across borders. And like liberal and Marxist thought, these ideas were often adapted in creative ways by the thinkers who imported them.

You have cited some examples of thinkers who adapted List’s ideas in interesting and different ways. Some of them lived in places where List’s protectionist advice could not be followed because of external constraints, such as trade treaties in Matsuakata’s Japan or British colonial policy in Ranade’s India. In this context, they developed innovative ideas about how to pursue neomercantilist goals in other ways. Matsukata, for example, devoted more attention than List to how a central bank could serve developmental goals through mechanisms such as direct lending to firms. Ranade called for Indian industrialization to be supported not just by the direct financial support of colonial authorities but also by the consumption behavior of Indian colonial subjects. Ranade also challenged List’s ideas about tropical countries being suited for manufacturing as well as the German thinker’s positive view of the impact of British imperialism in India.

The case of the British tariff reformers was also particularly intriguing in light of contemporary developments. List was focused on advising countries on how to catch up to British wealth and power. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, some British thinkers began to see his neomercantilist advice as useful for addressing their country’s declining global dominance. Citing the use of tariffs, subsidies, and other activist policies by rising powers, they argued that Britain needed to follow suit and abandon its free trade orientation. Their ideas foreshadowed those of American neomercantilists in the current age.

There were many other interesting examples of how List’s followers modified his thought. For example, while neomercantilists were united in their support for strategic trade protectionism, many of List’s followers did not follow his warning that trade restrictions should only be moderate, temporary, and specifically targeted. They also often endorsed much more extensive government economic activism at the domestic level than List had. Many later neomercantilists also rejected List’s political liberalism, such as the conservative Sergei Witte, who served as finance minister in autocratic Russia between 1892 and 1903. Indeed, neomercantilist thought in the pre-1945 era was associated wide range of political orientations, from that kind of conservative one to more left-wing positions such as Sun Yat-sen’s Chinese socialism.

AG: The American political economist Henry Carey (1793-1879) is a major figure in the book. In your estimation, he was almost as influential as List. What was Carey’s agenda as it relates to theorizing the “American System,” and what prompted him to embrace the neomercantilist cause? You note that his ideas significantly influenced American trade policy in the 1860s at the beginning of the Lincoln administration and that he has been described as “the ideologist of manufacturers” (139). Importantly, he was especially sensitive to the “domestic distributional and social costs of free trade” (148). Although this phrasing is quite loaded today, was Carey a kind of ‘populist’?

EH: In my view, Carey has not received the attention that he deserves, at least from IPE scholars interested in the history of neomercantilist thought. One reason I think he should be more studied is the one you have highlighted: his distinctive interest in domestic distributional issues. Carey saw trade protectionism as a policy that would not just bolster state wealth and power as a whole but also help to address domestic social inequalities, including gender inequality. He was also interested in its environmental benefits, arguing that free trade exhausted local soils by encouraging unsustainable export-oriented monocrop agriculture. Neither of these ideas can be found in List. Carey also did not share List’s enthusiasm for imperialism and believed that all regions of the world should be encouraged to industrialize, including the “tropics” (which, as already noted, List assigned to a permanent role of commodity-exporting).

Carey deserves more attention not just because of the distinctiveness of his neomercantilist ideas. These ideas were also very influential. In Carey’s own country, protectionists in the second half of the nineteenth century were informed much more by his thought than List. Like List, Carey also became well known in neomercantilist circles around the world. His most famous work published in 1858-9, Principles of Social Sciences, was quickly translated into many languages. And when his ideas diffused abroad, there were often more influential than List’s in fostering opposition to free trade, including in contexts as diverse as early Meiji Japan, post-Confederation Canada, and even Bismarck’s Germany.

Was Carey a populist? I guess it depends on how populism is defined. His writings indeed involve strong attacks on internationally-oriented economic elites that foreshadowed those made by contemporary politicians often described as populist. His specific targets were “traders” (149), a category that included groups such as financiers, commission merchants, shippers, and brokers. In his view, these rootless elites enriched themselves at the expense of producers (such as farmers and workers) and consumers through price manipulation, monopolies, and the fostering of race-to-the-bottom global market pressures. Also similar to some contemporary right-wing American populists today was Carey’s focus on tariffs at the border without much interest in domestic kinds of government economic activism to address inequalities.

AG: East Asia has long been associated with “developmental states” (201) and the statist orientation of East Asian political economy has received ample scholarly attention. In the middle portion of the book, we read about the origins and development of Japanese and Chinese (and to a lesser extent, Korean) neomercantilist thought, encountering figures who built upon mercantilist ideas, local traditions (e.g., Confucianism and Legalism; Japanese “Kokueki ideology”), and Western political economy. Why is it so crucial to understand the “importance of the regional intellectual context in which East Asian mercantilist and neomercantilist ideas emerged” (206)?

EH: It is often assumed that the East Asian developmentalism has its intellectual origins outside the region. A common story is that Meiji Japan’s successful state-led industrialization was informed by the ideas of List (and Carey) and that its model was then exported to the other East Asian countries. It is certainly true that List and Carey were read in Meiji Japan (and later in the rest of East Asia), but this Western-centric diffusion narrative overlooks important local roots of East Asian neomercantilist thought.

In the Japanese case, these roots can be found in what Luke Roberts calls the “mercantilism” of inter-domain competition in Tokugawa Japan. After the Meiji Restoration, mercantilist ideas emerging from that local context were transferred to Japan as a whole, serving a challenge to imported Western economic liberalism. After the Opium Wars, Chinese thinkers also developed important neomercantilist ideas, building on earlier indigenous traditions of thought, dating as far back as the era of the Warring States. A similar story can be found in Korea after its forced economic opening in the 1870s. An intra-regional circulation of ideas also informed and strengthened neomercantilist thought in all three countries.

Recognizing these endogenous roots of East Asian neomercantilism is important not just to correct the historical record. It also helps explain distinctive features of neomercantilist thought in the region, some of which have left legacies in the region to this day. Further, it calls attention to innovative thinkers who presently receive no attention in IPE textbooks, such as Japan’s Ōkubo Toshimichi and Fukuzawa Yukichi, China’s Zheng Guanying and Sun Yat-sen, and Korea’s Yu Kil-chun. More generally, this history highlights how neomercantilist thought emerged in the pre-1945 era in a more decentralized manner than economic liberalism and Marxism. Put simply, List was far less central to this process than Adam Smith or Karl Marx were for the emergence of economic liberalism or Marxism.

AG: The final sections of the book are dedicated to a discussion of neomercantilist thought and policy practice in Russia, Canada, Egypt, Poland, Latin America, and Africa. The Russian, Nikolai Semonovich Mordinov, was a “defensive neomercantilist” (285). The Canadian John Rae was interested in the “power of invention” (290) and influenced John Stuart Mill. The Ottoman-Albanian leader of Egypt from 1805 to 1848, Muhammad Ali, engaged in heavy-handed developmentalism. José Battle y Ordóñez, who governed Uruguay in the early 1900s, rejected Marxian notions of class struggle in favor of a “superior social harmony” (322) predicated on the implementation of neomercantilist policies. The Asante Empire in West Africa in the late nineteenth century was characterized by strong forms of autocratic neomercantilism. And with respect to Pan-African thought, we encounter Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), who pursued what you call a form of “diasporic neomercantilism” (328). What unites and distinguishes this group of thinkers?EH: These figures are united by the fact that their neomercantilist thought also emerged quite independently from that of List. Aside from that, they advanced very different versions of neomercantilist thought. Some of them were also practitioners and policymakers more than theorists. Muhammad Ali, for example, left no treatise of any kind, but I included him because he implemented the most ambitious neomercantilist policies anywhere in the world during his rule. He justified his innovative initiatives in discussions, speeches, and letters in ways that reflected a neomercantilist mindset, but one that was very different than that of List. The Asante leadership also wrote no treatises defending their distinctive neomercantilist policies that were focused on a high degree of state control of their empire’s commerce, until the British annexed their territory in 1896. Even more distinctive were the ideas of Marcus Garvey, who sought to cultivate the wealth and power of the Pan-African community through what I suggest was a diasporic neomercantilist vision.

In contrast to Ali and Garvey, Mordinov and Rae both wrote lengthy scholarly treatises (and before List’s famous 1841 book was published). Rae, in particular, deserves to be better known today. His 1834 book Statement of Some New Principles on the Subject of Political Economy is a very sophisticated (and over four hundred pages) defense of strategic protectionist policies and critique of some aspects of Adam Smith’s work. Written in what Rae called the “Canadian backwoods,” the book attracted little attention at the time of its publication. Rae appears to have been so disappointed by its reception that he abandoned work on political economy altogether and did not even own a copy of his impressive book in his later years.

As you note, however, Rae’s book subsequently gained more recognition when John Stuart Mill endorsed its defense of infant-industry protectionism in a brief passage in his famous Principles of Political Economy (1848). That unusual endorsement was used to justify protectionist policies in many countries and proved very controversial in nineteenth century liberal circles. Indeed, on his deathbed, the famous British free trader Richard Cobden is reported to have declared in 1865 that Mill had “done more harm by his sentence about the fostering of infant industries than he had done good by the whole of the rest of his writings” (54).

AG: We have clearly entered a kind of “post-1776” moment, marked by a waning pro-globalization consensus and the “revival” of neomercantilist thinking and policy practice across the globe. In the United States, the Biden administration seeks to affect a “pivot from market-liberal neoliberalism to state-interventionist ‘Hamiltonianism.’” More broadly, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has spoken of a “new Washington Consensus,” which refers to a recognition of the limits of free-trade dogmatism and the emergence of a “new global economic order.” Of course, “neomercantilism with Chinese characteristics” is nothing new, and neither is Chinese ‘party-state capitalism.” How do you feel, as both a scholar and commentator, about the escalating global neomercantilist turn, as it were?

EH: In my book, I note that neomercantilist ideas often gained prominence before 1945 during heightened geopolitical uncertainty and tension. Their popularity also often grew when states were experiencing growing economic vulnerabilities associated with trends such as the emergence of new economic competitors or intensified economic interdependence. In light of this history, it is not surprising to me that neomercantilist thought is undergoing a resurgence at this moment, including in the United States. It has gained strength from many developments, including the intensification of the Sino-American economic and geopolitical rivalry, the growing backlash against free trade in the United States and elsewhere, the increasing weaponization of economic relations, the accelerating rate of technological change (including in the realms of green and digital technologies which are both so central to human futures), and the international economic instabilities and vulnerabilities associated with the pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Some of these developments are winding down already (such as the pandemic), and others may prove relatively short-lived. But many of these trends are likely to be quite long-lasting. In that context, the revival of neomercantist thinking and policy seems unlikely to quickly be reversed. Another reason is that neomercantilist practices tend to feed off each other. Once one major state moves in a neomercantilist direction, others fear losing their competitive position in domestic and global markets if they do not follow. Indeed, famous neomercantilist thinkers such as Hamilton and List played to those fears by highlighted how rival states were already pursuing the policies they were recommending. We are witnessing the growing political prominence of this kind of argument today in countries across the world.

If we are likely to be stuck in this neomercantilist moment for some time, I think it is important to remind its advocates that neomercantilism need not be associated only with inter-state rivalry and conflict. Many past neomercantilist thinkers believed strongly in the importance of multilateral cooperation and some developed innovative ideas about it. List, for example, developed one of the earliest proposals for a “world trade congress” as far back as 1837. Sun Yat-sen was one of the first thinkers to call for a multilateral development institution in 1920. These thinkers showed how neomercantilism can be compatible with creative initiatives to strengthen multilateral cooperation. Given the many serious problems facing humanity today, contemporary neomercantilists should be encouraged to embrace this cooperative impulse and foster innovative forms of multilateralism that can preserve and bolster international cooperation in the new global context in which we find ourselves.

Addis Goldman is a writer and researcher based in New York City. He holds a BA from Colorado College and an MA from the University of Chicago.

Edited by Andrew Gibson

Featured Images: Utagawa Hiroshige III, “View of the Seafront in Yokohama” (1870). Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

John Trumbull, “Alexander Hamilton” (1806). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Friedrich List. Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Adrian Lamb, “Henry Charles Carey (1793-1879).” Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.