By Alexander Collin

Gianamar Giovannetti-Singh is a Freer Prize Fellow of the Royal Institution, incoming Lumley Junior Research Fellow in History at Magdalene College, Cambridge and a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow (2023–26). He completed his PhD in 2023 with a dissertation on how the Manchu conquest of China in 1644 transformed the sciences across Europe. The dissertation reorients common accounts of the history of science by showing that several scientific debates typically deemed “European” originated in China. His postdoctoral project, “Southern Africa and the Early Modern Globalization of Knowledge,” aims to examine how early modern Europeans drew on their knowledge of East Asia to make sense of the unfamiliar at the Cape of Good Hope.

He spoke with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article, “Astronomical Chronology, the Jesuit China Mission, and Enlightenment History” (volume 84, issue 3).

Alexander Collin: In keeping with the spirit of your article, which is so much about the agency of Chinese scholars and political actors, let’s start with the astronomy itself. What is it that is distinctive about the Chinese astral sciences, either conceptually or technically, that makes them so attractive and interesting in this period?

Gianamar Giovannetti-Singh: First of all, I should stress that I’m not primarily a historian of Chinese science or a Sinologist, but more a global historian of “European” sciences, so others will have more informed views on this subject. For me, the most interesting thing about the Chinese astral sciences is their inseparability from matters of political power. Chinese astral sciences tended to be divided into two branches: One, tianwen—roughly “heavenly writing”—had some similarity to judicial astrology in Europe and involved interpreting signs in the skies and determining their effects on the earthly and human realms. The other, lifa, had to do with calendrical calculations. What connected these two sciences was their relation to politics. Practitioners of lifa would try to predict the time of astronomical events in the night sky, and based on how accurately they predicted them, experts of tianwen would then construct a narrative around that, linking it to the legitimacy of particular imperial political actions.

AC: And structurally speaking, in terms of the personnel, you have people doing the astronomical, technical prediction side of this and people on the political side of this; are they the same people, or are they distinct intellectual and professional groups? How does this work institutionally?

GGS: So, each dynasty from the late Zhou (1046–256 BCE) in the third century BCE onwards has an astronomical bureau, called the Qintianjian in Chinese, or the “Tribunal of Mathematics” by Jesuits, which is staffed by civil servant astronomers responsible for the observations and for designing the imperial calendar every year.

Within the astronomical bureau, though, there were different sections. So, there was a Muslim section, established during the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), a Han Chinese section that followed the “Grand Concordance” system of calculation, and a Christian section, which began with the Jesuits in 1644. It was a fraught environment where each group was competing to make the most accurate predictions. And these predictions would then be used by politically inclined officials, not necessarily by the people who made the observations themselves.

AC: When the Jesuits first establish their missions in China, are they coming with a preexisting knowledge of or interest in Chinese astral sciences? Or is this something they develop as they’re there on the ground?

GGS: It is something that’s largely developed on the ground in China. The Jesuit mission in China began in the 1580s. Two Italian missionaries, Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri, were the first Jesuit missionaries to enter China, although the Jesuits had been interested in East Asia since the very start of the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits assumed that China had a strong cultural sway on religion elsewhere in East Asia, especially in Japan. They thought that if China converts to Christianity, then all of East Asia will follow.

Ricci and Ruggieri first entered the Ming Empire (1368–1644) in the 1580s. Initially they would dress as Buddhist monks, shave their heads, and try to pass as Indians. Then, in the 1590s, there was a shift, a rejection of Buddhist dress in favor of Confucian scholar-official dress. Ricci realized quickly imperial China was a polity, at least rhetorically, governed by heaven: The emperor was tianzi,the son of heaven, the empire was tianxia, all under heaven, and the emperor ruled legitimately because he hadtianming, the mandate of heaven. So, when he writes back to Rome in 1605, he says, send me an astrologer.

AC: In the article, you talk about Martino Martini acting as a representative of the Qing dynasty towards Europe. Is that something he is coordinating with officials and political actors in China with regard to how they want him to represent them?

GGS: I think in terms of Martini’s representation of the Qing (1644–1912), he’s very conscious that they’ve won the war. He travels up to Beijing once the Qing have established the empire and have taken Beijing, whereas his rival, the Polish Jesuit Michał Boym, isn’t in that same geographical context. Having stayed in southern China, where the remnants of the Ming imperial family fled, Boym knows the Ming and travels back to Europe and unsuccessfully tries to represent them. Martini wants to return to China to continue his missionary work, and he knows that to survive he’s got to back the Qing.

Martini was incredibly good at locating powerful people and making himself their ally. There’s a brilliant article by Mario Cams in Renaissance Quarterly from 2020 that looks at what he calls a double displacement: On the one hand, Martini moves from a Portuguese Padroado Catholic network to a Dutch one on the European side; and then in China he moves from the Ming to the Qing. He gets lucky both times.

On his first return journey from China to Europe, after setting off on a Portuguese ship, he gets captured by the Dutch and taken and imprisoned in Batavia. Rather than saying, no, I’m Catholic, I won’t say anything, he gives the VOC a copy of his atlas of China and even tells them there’s a new dynasty that is much more willing to do trade with them than the Ming were.

To reward him, the VOC grants him free travel back to Europe. When he stops at the Cape Colony, just set up in 1652 by Jan van Riebeeck, he is hosted by van Riebeeck, and he tells him where the Portuguese get their gold and where they enslave people in Mozambique. So he’s always selling himself, practical knowledge, and those close to him, when he realizes it’s necessary for his survival.

AC: Do you have a theory of where that characteristic comes from, that skill that Martini has for finding allies and fairly ruthlessly exploiting what he needs to get close to people? Where does he learn that?

GGS: He’s a born go-between. He’s born in the city of Trento in what today is Italy, but at the time it was the southernmost part of the Holy Roman Empire. He grew up with Italian-speaking parents, but the city was trilingual: people spoke German, Italian, and Ladin. And when other Jesuits ask him in Goa whether, he’s Italian or German, he always says, neither, I’m from Trento. He refuses to be stuck with one identity, and I think that’s strongly reflected in his ability to play both sides.

AC: The second part of your article deals with the reception of Martini’s work in the eighteenth century. As a kind of bridge here, could you fill in what is happening with his work in between the period when he’s producing it and then this later period where it’s being picked up by Voltaire and Fréret and all these French thinkers? What’s the transition phase there?

GGS: So, the background context in both China and Europe is the Chinese Rites Controversy, which I wrote about in Modern Intellectual History a couple of years ago. It’s a vicious fight between different Catholic orders, but also within the Jesuit order to some extent, about whether Chinese converts to Christianity should be able to 1) continue to worship their ancestors and Confucius and carry out rites in honor of Confucius and their ancestors and 2) whether they should be allowed to use Chinese words to refer to the Christian God: the words tian, which means heaven, and Shangdi, which is like Supreme Emperor.

The Jesuits, generally, were in favor of allowing Chinese converts to maintain these practices. Matteo Ricci had said: it’s okay, we’re applying a policy of accommodation that will allow us to have a foothold in China. One of the accommodationist arguments was that these rites were practices that long predated Chinese religion’s degeneration into paganism. This was a kind of natural theology, a natural Christian theology.

Other Catholic orders completely rejected this position, and the Holy See sent a legatus a latere, Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon,as an investigator to Beijing in 1705–6, and he ultimately ruled against the Chinese Rites. This controversy made many things Chinese appear rather risky in Catholic Europe. There were still efforts to excavate the deep Chinese past in Europe, but the papacy’s rulings against this made Chinese history a more controversial topic.

So, on the one hand, Catholic Europe is wary of things Chinese because of the rites controversy. On the other hand, Protestant Europe is wary too, because people consider Chinese history to be too closely linked to the Jesuits. There is a view that that if one accepts Chinese astronomy and Chinese history, one ends up accepting Chinese political despotism as well. There are substantial debates about despotism as a form of politics. So that sets the scene for this later reappropriation of Martini and other Jesuit writings by Voltaire and Fréret.

AC: In the background of many of the French texts, is a response to Newton. Could you expand on Newton’s contribution a little. What does Newton actually know about the Chinese astral sciences? To what extent is he responding on a scientific and scholarly level and to what extent is it just politicization and prejudice and intra-European religious quarrelling?

GGS: So, Newton owns a copy of Philippe Couplet’s book on Confucius and its appended Tabula chronologica, which is basically Martini’s chronology with a few tweaks. Newton has read this book; it’s a very dogeared copy that he’s clearly looked at a lot. But he rejects it totally and refuses to engage with the Chinese historical or astronomical literature. He writes that ancient Chinese astronomical records are but “a fable invented to make that Monarchy look ancient.”

Like most Europeans, Newton fully buys into the story of the book burning in 213 BCE. It’s a story that one of the emperors of the Qin dynasty, Qin Shi Huang, had burned all the books, bar those on medicine, divination, forestry, and agriculture. So Newton says, if that’s the case, there’s no way that you can recover anything about older Chinese histories. And Newton is of course also interested in biblical chronology, so he takes the four kingdoms from the book of Daniel to be the four kingdoms that were there in the earliest antiquity, and China is not there.

He tries to explain China away. He thinks that the dynasties weren’t in sequence, but they existed in parallel. And he makes the same argument that you find in John Marsham’s work about Egypt; Marsham also says the pharaohs’ dynasties don’t actually stretch that far back because they actually existed in parallel. There’s a project I’m working on at the moment, on an English Anglican astronomer and orientalist called George Costard.

Costard was a hardcore Newtonian and he defended Newton even for his most outlandish claims, launching a vicious polemic against Antoine Gaubil, a French Jesuit in Beijing, about how old Chinese chronology actually is. Costard’s argument is intensely political. He says, if Chinese astronomy is the purview of the state, and if astronomy is used to back up an incumbent’s political power, then how can we possibly trust astronomic observations? Surely any incumbent emperor will just mark observations that indicate he’s doing well.

AC: I’d like to talk a little bit about legitimation of different bodies of knowledge, which is an issue you raise in the article. Where do you see the bounds of the legitimacy created for Chinese data? Is it a specific, astronomically oriented, scholarly legitimacy? Or is it something broader among educated European society?

GGS: I think it has a very wide scope, but it uses different types of evidence to convince different people. For example, Martini, when he comes back to Europe, he lectures all over Northern Europe. At Louvain, he has a magic lantern show to try and amaze his viewers into believing the story. And in fact, one of the people in the audience was Philippe Couplet, who ends up taking up the call and going to China. And then in Leiden, Jacob Golius, the Orientalist and mathematician, has an “enlightening encounter” with Martini, who convinces him that “Cathay” was China—a lively debate among European Orientalists at the time.

One thing that’s quite interesting in terms of legitimacy of different kinds of sources from China is Martini’s connection to Athanasius Kircher, who was his personal mathematics tutor in Rome. Kircher wrote a lot about Chinese antiquity, but he predominantly focused on material things as a source of information, reflecting his own enculturation in a museum in Rome and in his earlier life with Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc in Aix-en-Provence. So, for example, Kircher received a rubbing of a stone monument dug up in 1625, which has a Coptic cross at the top. He takes that as unquestionable material proof that Christianity has been in China since the seventh century CE. That’s very, very different from Martini’s arguments.

For Martini, it’s all about the astronomical records. Those can be corroborated. There are astronomical tables that can allow you to wind back the clock, to see what the sky would have looked like at a given moment in the past. So there’s a shift that’s happening in, I think, the mid-seventeenth century, toward presenting astronomy as the grounds for what counts as evidence and what counts as something credible. Even though, as we’ve seen people disagreed very strongly about astronomy.

AC: Could you perhaps talk a little bit about how you came to be interested in the work of Alex Statman, how it’s been influential on your own work?

GGS: It’s been extremely important and inspiring during my PhD. Statman’s paper, “The First Global Turn,” came out in 2019, just as I was starting my PhD. I was completely struck by his argument that Europeans didn’t only learn about Chinese history, but they thought that they could learn from it to rearticulate their understandings of European history by connecting the two.

Chronologically, his new book, A Global Enlightenment (which I have reviewed for the Los Angeles Review of Books) focuses on a much later period; it’s examining the 1770s to the 1820s. I love the book, and I agree entirely with its central claims. I think a key difference between our work is that for me the collapse of the Ming dynasty is a key moment that rapidly opens Europe to all things Chinese. He focuses very much on Enlightenment, but I think for me, making sense of 1644—the “Tartar Moment”—and its resonance across the world, is key to understanding early modern European ideas about China, the mandate of heaven, and East Asian sciences.

AC: In closing, I’d like to come to your conclusion. You end the article saying that “the article has shown that the polemical promotion of Chinese astronomical chronology took place because it was in the interest of disparate groups of actors as shaped by local political circumstances, not because it offered a necessarily superior way of understanding the past.”

When you say “not because it necessarily offered a superior understanding,” I feel like “necessarily” is doing a lot of the work there. I’m interested in the extent to which you’re saying that this is a contingent political form of argumentation and the content of the astral sciences is unimportant or superficial there. And to what extent are you arguing that the astral sciences’ content is important but would not be as influential without the political impetus. How do you balance those two perspectives?

GGS: I struggled with this question throughout my entire PhD, it’s one of the most difficult issues I deal with. Tony Grafton’s extensive work on astronomical chronology in Europe has been incredibly important to show me it’s not just this moment in China that brings astronomical chronology to Europe. Europeans since Greco-Roman antiquity were referring to astronomical events in historical annals. So that tradition is absolutely there in Europe already.

What’s interesting about this case, and this is where I think it becomes entirely political, is how can one trust a science that is clearly not a European science? Some Jesuits try to make the argument that ancient Chinese science was ancient European science. They say, it all goes back to the flood when Noah taught his sons astronomy and it’s the same tradition. For them, that’s why it can be trusted. And funnily enough, the Chinese had exactly the same justification for engaging with “western ocean learning,” or xixue. They said, this is just ancient Chinese science in its pure form, and what we have here today has degenerated and decayed over the millennia. So both sides had exactly the same argument.

But I think where the political comes in is that astronomy could very quickly become a political resource in Europe because it was such a well-established political resource in China. So, I think, yes, China is an agent in this story. But one of the reasons why Chinese astronomy and astronomical chronology could go so far in Europe was because many European rulers realized rather quickly how valuable it could be to have your own rule legitimized by the heavens. Translating Chinese cosmopolitics for an elite European audience could be extraordinarily valuable. For example, you can see this recognition among the Physiocrats in the late eighteenth century.

They adopt a Chinese cosmological framework to explain how France can rebuild after the devastation of the Seven Years’ War. They get the French crown prince Louis-Auguste to till the soil in June 1769, which is an imitation of a Chinese New Year ceremony, where the Emperor tills the soil to restore balance between heaven, earth, and human. If the French monarch can become the Son of Heaven, like the Chinese emperor, then he can lay claim to far more power than he even already has.

AC: Thank you. So, one final question: What are you working on now? Where do you go next? What can anyone reading this interview look forward to from you?

GGS: I’m currently writing my book, The Tartar Moment, to really focus on how the collapse of the Ming dynasty completely transformed Europe’s relationship to China, globalized Chinese sciences, and brought about a new naturalization of cosmopolitics in Europe. It looks at cartography, astronomy, history, military technologies, and agriculture. So that’s one project.

Otherwise, I’m starting a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship in the History Faculty at Cambridge and a Junior Research Fellowship at Magdalene College in October. The project there is actually to look at what happened to these Asian cultures of knowledge as they stopped in South Africa on the way back to Europe. Focusing on South Africa as a place that transformed and was transformed by this new globalization in the early modern period.

Alexander Collin is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam where he works on northern Europe from the 1490s to the 1700s. His doctoral thesis aims to test the historical applicability of theories of decision making from economics and organizational studies, considering to what extent we should historicize the idea of ‘The Decision’ and to what extent it is a human universal. The project has been funded by the Leverhulme Trust and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst. Alexander has written for The Historian magazine, Shells and Pebbles, The History of Knowledge Blog, as well as academic publications. Alongside his historical work, he also contributes reports to the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. He studied at King’s College London, Humboldt University Berlin, the University of Cambridge, and Viadrina University Frankfurt.

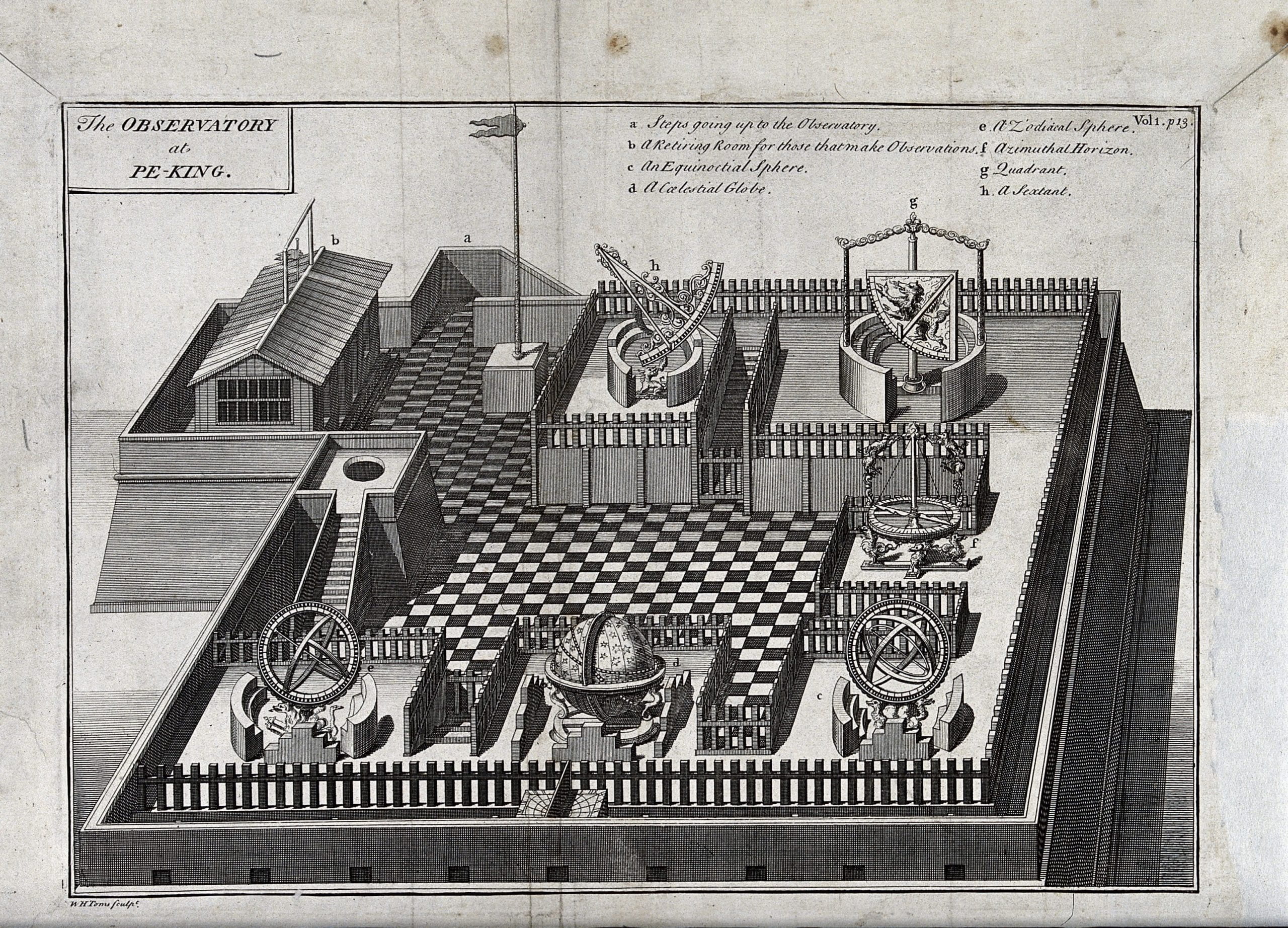

Featured image: The open air Observatory, Peking, China: A Celectial Globe, Quadrant and Equinoctial Sphere, Sextant, Azimuthal Horizon and Zodiacal Sphere, made by Jesuit priests from the original Chinese models, at the Ancient Observatory, Peking. Engraving. 1797. Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0.