By Seyla Benhabib, Andrew Gibson, and Artur Banaszewski

The latest issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas (issue 84, volume 3, July 2023) features the article by Samuel Moyn “Hannah Arendt among the Cold War Liberals.” The article places Arendt’s thought alongside that of her liberal contemporaries—such as Isaiah Berlin, Jacob Talmon, Judith Shklar, and Karl Popper—and argues for a reassessment of the “contributions and limits of her project in political theory” (533). We invited three scholars specializing in Arendt and Cold War liberalism—Professor Seyla Benhabib, Andrew Gibson, and Artur Banaszewski—to write responses to that important article. Please note that the responses were written before the authors had access to Professor Moyn’s forthcoming book, Liberalism Against Itself: Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times.

Seyla Benhabib

Samuel Moyn is a provocative writer. He regards theoretical disagreements, differences of interpretation and scholarly contestations agonistically, as a fight in which it is existential that those who disagree with him be freed from their delusions and misunderstandings. Thus, a phrase in his article states that “Generations of instrumentalizing, opportunistic, or promotional readings have obscured the relationship that Arendt sustained with Cold War liberals.” Moyn is out to set them right.

Alas, Moyn’s central argument—that even if Arendt was not a liberal, “her very attempt to strike out on her own in developing a new account of freedom proves hostage to many of the intellectual and political premises of Cold War liberalism”—is vague and confused (534; my emphasis). “Proves hostage” is an interesting phrase: does Moyn mean that Arendt was simply influenced by Cold War liberals such as Isaiah Berlin, Jacob Talmon, or Karl Popper? There is no evidence for this, and Moyn only cites that Arendt possessed a copy of Talmon’s book – Origins of Totalitarian Democracy. So, “proved hostage” seems to mean some kind of convergence of ideas and orientations, despite differences between Arendt and Cold War liberals, which Moyn himself acknowledges.

Moyn’s presumption of convergence centers on ‘totalitarianism’ to characterize both Nazism and Stalinism. Unlike classical Anglo-American liberalism, Arendt’s work had little to say about economics and markets, and furthermore, unlike Cold War liberals, she retained in Moyn’s words, “an early nineteenth-century commitment to creative perfectionism” (an aspect of liberal thought appreciated by Nancy Rosenblum). How then does Arendt’s critique of totalitarianism make her a Cold War liberal? In order to place Arendt in the procrustean bed he has created, Moyn radically neglects the milieu out of which Arendt’s critique of Stalinism and developments in the Soviet Union grew.

Arendt was an anti-totalitarian before she came to the United States; she did not become one subsequently. Neither the change in the title of the book from The Burden of our Times to The Origins of Totalitarianism nor subsequent additions (Moyn, 540) alter the fact that Arendt’s views of totalitarianism began with accounts of the failures of the German KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands) to which her husband Heinrich Blücher belonged. As Elizabeth Young-Bruehl recounts, she was intimately familiar with the milieu of ex-communist militants who would be called back to Moscow to be murdered or re-educated; with those who fought against fascism in Spain, only to be betrayed by Stalin; and those, like members of the French Communist Party, who did a volte-face in 1939, when the Hitler-Stalin pact was signed (139). Arendt also held on to a belief, which many may consider controversial, that “only Stalin’s regime and not Leninism was, properly speaking, totalitarian” (410). Admittedly, pointing out that Moyn misconstrues the origins of Arendt’s theory of totalitarianism says nothing about the merits of the theory itself, which Moyn hints at but does not engage with.

Moyn refers to my book, Exile, Statelessness and Migration. Playing Chess with History from Hannah Arendt to Isaiah Berlin as “biographically essentialist.” The term ‘essentialism’ is a philosophical concept that postulates the presence of some immutable and fundamental characteristic of phenomena; what exactly is Moyn referring to? This is also a deep misreading of my book since the whole point was to emphasize the divergent paths taken by thinkers such as Arendt, Benjamin, Berlin, Hirschman, and Shklar despite biographical interconnections and overlaps.

Moyn’s critique of Arendt’s comparative analysis of the American and French Revolutions is not new. Jürgen Habermas challenged Arendt’s account nearly 60 years ago, and Judith Shklar called Arendt’s book a “valentine presented to America.” What is novel in Moyn’s assessment is that Arendt’s account of the French Revolution, and her claim that the Revolution was stymied because of the enormity of economic poverty and inequality, made her blind and deaf towards decolonization struggles in the developing world. I agree with Moyn that Arendt, who wrote enthusiastically about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, should have focused her political brilliance on writing about the Algerian War and Revolution of 1954-1962, as well. But Moyn overshoots again when he writes that “Arendt was open and unapologetic when it came to her imperialist and racist commitments” (548). Recent scholarship both praises Arendt for her path-breaking analysis of “race-thinking before racism,” which is not focused on the color line alone; while also showing the limits of her understanding of the fate of Black Americans. It should give Moyn some pause that many young African-American scholars—such as Danielle Allen, Adom Getachew, and Shatema Threadcraft—have nonetheless found it possible to cull from Arendt’s work, “pearls of wisdom” that they used in their own work.

Moyn’s concluding reflections are about Arendt’s “Jewish exceptionalism,” namely “her support for Jewish self-emancipation through Zionism … and her stringent attitude towards other forms of decolonization…” (533). As opposed to Moyn’s claim that Arendt’s Eurocentrism or racialism accounts for her Jewish exceptionalism, I would argue that it was her sense of the difficulties of the nation-state system, most vividly expressed through the following lines, that may have restrained her: “…like virtually all other events of our century, the solution of the Jewish question merely produced a new category of refugees, the Arabs, thereby increasing the number of stateless and rightless by another 700, 000 to 800,000 people. And what happened in Palestine within the smallest territory and in terms of hundreds of thousands was then repeated in India on a large scale involving many millions of people…” (290-291).

Arendt’s sense of the dead-ends which progressive politics could encounter was alleviated somewhat with the Civil Rights Movement, the Student Movements of 1968, and the anti-Vietnam War movement – all of which she followed avidly. Her last article for the New York Review of Books, “Home to Roost: A Bicentennial Address,” was a reckoning with the transformation of the American Republic into a deceitful, militaristic global power which had lost its sense of public happiness and public freedom and had turned into a consumer-society led by technocrats and Madison-Avenue style politicians. Judging by the reactions of Commentary magazine, other Cold Warriors did not agree. I think that Moyn sadly misjudged the company Arendt kept. These were the disillusioned militants who fought against both Nazism and Stalinism, as well as the early Zionists of the Kibbutz movement who saw Israel betray its ideals and become an ally of superpowers in the Middle East. Nonetheless, despite her unblinkered vision of the collapse of good intentions in politics, Arendt insisted on the capacity of each generation to begin anew and create a different realm of freedom.

Andrew Gibson

Great monuments, like all human things, eventually crumble. In his recent JHI article, Samuel Moyn seeks to add a few cracks to the columns of Hannah Arendt’s political thought, which has long held an outsized influence in the field of political theory. Reading the German-Jewish émigré alongside the “Cold War liberals,” Moyn suggests Arendt is “best understood as displacing the intellectual premises of earlier liberalism, while foreclosing a global approach to the universalization of freedom in equality in an era of decolonization and deracialization.” Writing to “reassess the contributions and limits of her project in political theory,” Moyn unsurprisingly concludes that Arendt’s writings no longer remain a helpful resource to understand our times, nor do they articulate a type of politics worthy of recovery (533). By narrowing the vistas of freedom in the mid-twentieth century and expressing panicked reactions to republican corruption and global emancipation, Arendt’s thinking remains fundamentally limited for thinking about “collective political freedom in the future” (558).

It is clear Moyn is eager to inspire his readers to search for an intellectual foundation more conducive to social, economic, and political liberation than the ones Arendt and her Cold War liberal colleagues provide. Yet, Moyn’s “Cold War liberal” designation sometimes appears more befuddling than illuminating as it casts over such divergent views on liberalism in the mid-twentieth century. Arendt never considered herself a “liberal,” as Moyn well notes; this fact requires him to frequently point out the many differences Arendt had with “Cold War liberals,” and even the gulfs separating those who would identify as such (534). Nevertheless, Arendt and her Cold War contemporaries do share some affinities. Citing recent literature, Moyn contends twentieth-century Anglophone liberalism departed from its earlier premises as it began to focus more intensely on “modernity, personal liberty, and religious toleration” while nineteenth century theorists concentrated on markets, parliamentary institutions, and a “perfectionist account of the creative highest life” (534). Moyn laments the excising of these earlier liberal traditions in Arendt’s writings. “Visitors to Arendt’s gallery of the annals of ‘Western civilization’,” he writes, “will find her walls […] almost completely barren when it comes to the Enlightenment and nineteenth century liberalism” (538). In its place, one finds monuments to the ancients and their conception of politics—particularly (neo)Roman republicanism.

Arendt famously analogized a form of political thinking to “pearl diving,” where one plumbs the depths of the sea of history to find old pearls of wisdom. During the Cold War, she found many “lost treasures” in (neo)Roman republicanism and spent much of her time “projecting the politics she prized backward, associating agency with Rome and the neo-Roman American origins” (541). These artifacts remain on display in On Revolution (1963) and are the subject of Moyn’s most incisive critiques. Here, we read that “Arendt joined Cold War liberal Atlanticism—but sought to defend and rehabilitate the Atlantic republican tradition with a more openly global perspective in the era when formal empire had come to an end” (537-38). Perhaps surprising to readers of the “smash hit” The Origins of Totalitarianism(1951), the ascension of empire mattered less in Arendt’s political theory than did the prospect of imperial decline. Once an empire “crossed irreversibly into decline, as she eventually ended up worrying America was doing in the era of its ‘crises of the republic’ and the Vietnam War,” the results could be just as catastrophic as those produced by a politics devoted to universal emancipation (549). One could almost say Arendt’s “pearl diving” was also a form of “pearl clutching.”

Forty years ago, Judith Shklar came to a similar assessment on Arendt’s catastrophizing tendencies: “Whenever something unfortunate occurred she thought that the end of the republic was near. (One does not forget Weimar easily)” (371). Moyn’s account shares much with Shklar’s early appraisal, suggesting The Origins of Totalitarianism“breathed new spirit into the concept of totalitarianism, which otherwise might not have endured after World War II when fascism disappeared as a living political endeavor” (539). Arendt’s panicked reaction to perceived republican corruption in the United States also made her view of Atlantic republicanism “far more bizarre” than the one offered by John Pocock in his masterful Machiavellian Moment (542). In On Revolution, Arendt idolized the American Revolution because it established political freedom without the “interference of economic justice” while she decried the French Revolution for unleashing a deranged pursuit of universal equality (541, 543). As Moyn states, Arendt’s attempted recovery of the “distinctive model of politics” she identified in the American Revolution became “critical for avoiding the totalitarian modernity that the French Revolution anticipated” (541-2).

Like other German-Jewish émigrés, Arendt wrote on the American political tradition to teach citizens of her adopted country about their exceptional history and distinct political virtues. As a wise sage steeped in German Bildung, Arendt offered counsel and comfort to Americans in search of meaning. But to those outside the United States, her teachings were less sanguine as she effectively narrowed the horizon for legitimate political activity and shunned revolutionaries from the Global South from being worshiped in the Cold War liberal pantheon. As Moyn suggests, one way of reading Arendt historically is seeing her “globalize her skepticism of the French Revolution’s legacy in a decolonizing age,” making On Revolution read as “postcolonial derangement” (543, 550). Given that Arendt’s early philosophical education was permeated with racial and hierarchical theories, Moyn also contends her “clear assumption [was] that non-white revolution would necessarily channel French manias.” If she had written on the Haitian Revolution, she would surely have found it “pathological, merely worsening […] the French syndrome, by welding political freedom not just to class but also to racial equality” (550).

All of this comes as a surprise to a theorist who famously articulated a romanticized vision of political action in The Human Condition (1958) and praised Zionism early in her career. Yet, to Moyn, Arendt’s romantic vision of action made “freedom […] elusive to the point of foreclosure” (552). Because her vision of action was associated “exclusively with so exceptional and even melodramatic a set of examples,” she ended up “rendering action incompatible with institutional life” and embraced the “geographical morality” commonly held by Cold War liberals (536, 557). For these reasons, among others, Moyn concludes Arendt’s project “ought to be treated as irretrievable in our time” and cautions against retreating to the monumental histories constructed by her and other mid-century thinkers (537). After reading Moyn’s article, however, one wonders what should be erected atop the ruins of Arendt’s thought—and Cold War liberalism, more generally. Should the ambitions of the earlier liberalism be recovered, once stripped of all their faults? Or, are we required to build this broader vision of collective human freedom on entirely new foundations?

Artur Banaszewski

Few twentieth-century scholars can rival the fame and influence of Hannah Arendt. Arendt’s unparalleled status as an icon of modern philosophy makes any critical engagement with her ideas a concurrent comment on the present state of political theory. While Samuel Moyn refrains from explicit criticism of Arendt’s contemporary interpreters and imitators, “Hannah Arendt among the Cold War liberals” convincingly argues her thought is burdened with anxieties and insensitivities that restrict its emancipatory potential in our present age. This annotation may explain Moyn’s acknowledgment that “Arendt wasn’t a liberal, she repeatedly declared—and she was therefore not a Cold War liberal” (534). The ambition of the article is, consequently, not as much to list Arendt’s commonalities and differences with more archetypical Cold War liberals as to display how certain concepts and assumptions she developed contributed to a fundamental shift in liberal thought during the Cold War, which continues to condition liberal imagination today.

Although Arendt never renounced creative agency as the motivation and purpose of her philosophy, Moyn suggests her opposition to securing freedom through institutional means ultimately made the ambitions of her political project unattainable. This opposition constituted a radical rupture with the earlier liberal tradition based on the employment of political institutions to achieve social progress, which made Arendt contribute to the abandonment of “collective emancipation as an aspect of the liberal project” (536). The test of the validity of this position came with the wave of decolonization movements that swept the world in the 1950s and 1960s. According to Moyn, Arendt—alongside the Cold War liberals—failed that test miserably. This is where Moyn’s criticism resonates most strongly: instead of identifying with anti-colonial movements a chance to embrace freedom on a global scale, Arendt assumed that “globalizing postcolonial freedom was despotic in intent or effect” (551), which was grounded in a racialized, hierarchical outlook on the prospect of emancipation of different peoples (557). By choosing allegiance to empire (or avoiding imperial decline) over global liberation, Moyn believes Arendt rendered her legacy “irretrievable in our time” (537).

Although Moyn dedicates much space to the historical context in which the German-Jewish émigré thinker wrote, his argument, at its core, is theoretical: it concerns the contradictions and paradoxes underpinning Arendt’s theory of politics. His article formulates a compelling critique that challenges Arendt’s intellectual legacy. Yet, should we abandon it entirely?

While emphasizing Arendt’s imperialist and racist convictions, Moyn writes that “the intellectual premises of a good part of decolonization after 1945 were in the earlier liberalism that both Arendt and the Cold War liberals rejected” (537). Consequently, one of the questions his JHI article provokes is whether Arendt’s theory of politics can be separated from her unapologetic Eurocentrism and racism. Although Moyn admits Arendt never erected a “racial bar to achieving American freedom” (551), he seems to suggest a cognate bar nevertheless stemmed from her concern for the “enduring realities of human aggression or sin” (536). Even if one condemned and erased hierarchical and prejudiced assumptions of Arendt’s thought, this would not resolve her suspicion of liberation movements caused by programmatic trepidation for the “reality of extermination camps and slave labor.”

One may interpret the exception Arendt and the Cold War liberals made for Jewish self-emancipation as proof of theoretical inclusiveness rather than arbitrariness. Yet Moyn writes explicitly that their support for Zionism constituted “a fundamental challenge to their call for limits in developed countries and anxieties about meaningless violence in developing ones” (557). And so, Arendt and the Cold War liberals reserved the right to decide who could take issue with the reality of global hierarchy of power.

Arendt’s “betrayal” of the prospect of global emancipation appears, therefore, just as racialist as philosophical. In the latter case, Moyn argues Arendt’s refusal of “any notion of historical progress” stemmed from her categorical rejection of the Hegelian idea of dialectical movement towards freedom (546). This suggests that the “demonology of modern emancipation” Arendt shared with the Cold War liberals was, in her case, a response to her perceived bankruptcy of Hegel’s philosophy of history. Among the many writings where she criticized Hegel, Arendt particularly emphasized his moral misguidedness in On Violence: “Hegel’s and Marx’s great trust in the dialectical ‘power of negation’ […] rests on a much older philosophical prejudice: that evil is no more than a privative modus of the good, that good can come out of evil; that, in short, evil is but a temporary manifestation of a still-hidden good” (56). Although the evils Arendt had in mind are not to be dismissed lightly, Moyn challenges the reader to reconsider to what extent the erasure of progress from the philosophy of history contributed to the erasure of progress from our contemporary consciousness. If history is a struggle between the devil and God, the only thing we can look forward to is a Last Judgement.

In this capacity, Moyn unequivocally castigates Arendt and the Cold War liberals for establishing strict—presumably, overly strict—limits on the prospects for collective emancipation (536). However, the risk of governmental tyranny, alongside the reality of evil, were not the only factors that made Arendt reticent about the idea of global freedom—which relates to the Haitian Revolution she so notoriously ignored in her work. As Hegel famously declared in Phenomenology of Spirit, “it is solely by risking life that freedom is obtained.” An excerpt from the first pages of On Revolution could be taken as Arendt’s response to Hegel’s revelation: “To sound off with a cheerful ‘give me liberty or give me death’ sort of argument in the face of the unprecedented and inconceivable potential of destruction in nuclear warfare is not even hollow; it is downright ridiculous” (13). As Jonathan Schell notes, Arendt shared the conviction of many of her contemporaries that nuclear arsenals imposed absolute limits on political change through warfare (249).

Moyn aptly points out Arendt’s conspicuous disregard of the fact that even the American Revolution was a violent insurrection against empire (551). But should consistent support for global emancipation require equal opposition towards all hindrances and constraints to anti-imperial struggle? Or should it nevertheless admit certain limits resulting, for instance, from the principles of restraint and responsibility? There are no simple answers to these concerns, and their exposure by Moyn’s article proves only the far-reaching consequences that critical reassessment of Arendt and Cold War liberalism will involve for our political imagination.

Seyla Benhabib is a Yale University’s Eugene Meyer professor of political science and philosophy, emerita, and a senior research fellow at Columbia Law School. She is a distinguished international scholar who is known for her research and teaching on social and political thought, particularly 20th century German thought and Hannah Arendt.

Andrew Gibson is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Government at Georgetown University where he is writing a dissertation on the “transatlantic Machiavelli,” focusing on twentieth-century debates over the Florentine’s political-historical legacy. He has been a Hans J. Morgenthau Fellow at the Notre Dame International Security Center (NDISC) and a Doctoral Research Fellow at the German Historical Institute (GHI).

Artur Banaszewski is a Ph.D. researcher in the Department of History at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. His doctoral project titled “Disillusioned with communism. Zygmunt Bauman, Leszek Kołakowski and the global decline of orthodox Marxism” explores Eastern European critiques of socialist thought and intersects them with the global political context of the Cold War.

Edited by Artur Banaszewski

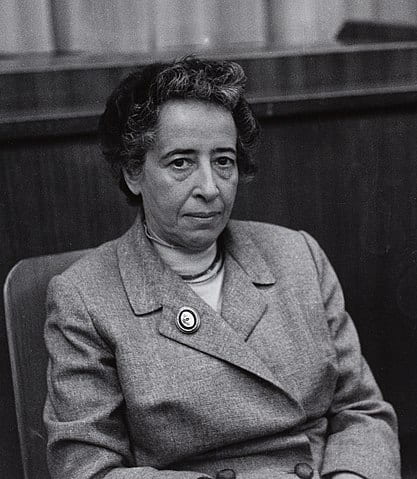

Featured Image: Hannah Arendt at the First Congress of Cultural Critics, photograph, Munich City Museum. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

1 Pingback