By Disha Karnad Jani

This post was simultaneously published on the conceptual history blog Komposita, which was initiated on the occasion of Reinhart Koselleck’s centennial this year. It follows previous cross-published posts by Sébastien Tremblay and Jonathon Catlin.

“Congealed manifestations of the term revolution can preclude our effort to think the event as experience,” wrote Elleni Centime Zeleke and Arash Davari in 2022. “If revolution signals the disruption of existing categories,” they ask, “can we in turn disrupt congealed categories to rethink revolution?” (423). Reinhart Koselleck was concerned with how this congealing happens in the first place—how experiences and terms accumulate into a “collective singular” or concept. Below, I draw from recent historical and political work to suggest that we take Koselleck more seriously, even against Koselleck, when he writes: “The primary interest of Begriffsgeschichte is its capacity to analyze the full range, the discrepant usages of the central concepts specific to a given period or social stratum” (65). If we pursue “discrepancy”and specificityover the now-ridiculous aspiration to any “full range” of meanings, a more useful method emerges. In our re-examination of Koselleck’s work on his centennial, I ask what happens when we turn one of his characteristics for modern concepts—the “simultaneity of the non-simultaneous”—on its head. Why, I ask, did his work on the modern concept of revolution and the revolutions of the 1950s-70s appear to him as inassimilable? The non-simultaneity of simultaneous events (as distinct from Ernst Bloch’s concept)—Koselleck writing on revolution while revolutions were also taking place around the world—suggests a way to read this Wehrmacht soldier, Cold War historian, and now-fashionable icon against himself.

Bernard Harcourt has characterized Koselleck’s “relation to the internationalist revolution” as “pessimism or disheartedness,” but Koselleck, in his 1969 essay translated as “Historical Criteria of the Modern Concept of Revolution,” did not even think of events outside of Western Europe as belonging to a single concept: they could not be “regulated” or “ordered” by it (50). Rather, they stood outside revolution: “…since the time when the infinite geographical surface of our globe shrunk into a finite and interdependent space of action, all wars have been transformed into civil wars” (56). Koselleck’s method is not inherently incompatible with analyses of contemporary politics; the observers of eighteenth and nineteenth century revolutions from whom he drew his historical criteria were useful precisely because theirs were moving targets. Indeed, one of Koselleck’s criteria was concerned with such instability: “the degree to which the prospect of the future continually altered accordingly changed the view of the past” (51). In describing living in a revolutionary time, as several of these criteria do, this method of diagnosing the “occasional very concrete meaning” of the concept was in fact deeply experiential and therefore deeply reflexive. Revolution (as concept) provided a “regulative” and “ordering” mechanism for understanding politics—if one believed oneself to be living in a revolutionary time.

Later in life, Koselleck argued that experience hardened inside a person like lava, making concepts pertaining to that experience difficult to parse. In contrast, recent work on twentieth century concepts has asked how we might conceptualize in real time. Scholars have taken up Koselleck’s reflections on modernity and time to analyze events beyond his concern, or indeed, ability. For instance, Manu Goswami and David Scott have made use of concepts such as “futures past” and the “space of experience”/“horizon of expectations” to describe the temporality of twentieth-century anticolonialism and the afterlife of the Haitian Revolution respectively. Dan Edelstein, Stefanos Geroulanos, and Natasha Wheatley’s edited volume Power and Time puts forth “chronocenosis,” a model for understanding time that foregrounds conflict between “temporal regimes” over sedimentation. Anson Rabinbach’s ongoing project, Concepts That Came in From the Cold,asks after concepts that emerged in the post-1945 years such as genocide and totalitarianism—concepts that could only have emerged during the twentieth century. A corollary of Rabinbach’s question might be: why did some concepts that pre-date the twentieth century in Koselleck’s Begriffsgeschichte appear to Koselleck as falling short of describing the present?

Indeed, it was the proliferation of the category of revolution across distant places—apparently threatening its coherence—that seemed to stymie Koselleck, even as the historical criteria he presented in the definition of the modern concept of revolution emphasized movement, adaptation, and canny political footwork by its participants and observers. The constant state of “civil war” he observed in his own time, coupled with the threat of nuclear Armageddon, formed a bind not only for humanity but for the work of conceptualization. In describing the withering of the early modern notion of the “civil war,” Koselleck notes its distinction from the twentieth century mutation: “from Greece to Vietnam and Korea, from Hungary to Algeria to the Congo, from the Near East to Cuba and again to Vietnam” (56). He described how concepts changed when their diagnosticians received new information.

Before 1789, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had suggested to Voltaire, among others, that “Revolution” could “open up a new vista” without bloody battles, whereas “civil war” became demoted to a “senseless circling” (49). Koselleck describes this as an “alien experience,” which transformed the concept of revolution and primed the emergence of its modern form. He throws up his hands in the final lines of this essay: “the clarification of [the reciprocal relation of the permanence of revolution and the fear of global catastrophe] can no longer be the business of a Begriffsgeschichte as presented here” (57). Eager to disabuse readers of the notion that he thought his definitions would apply forever, Koselleck ended with a reminder that Begriffsgeschichte is ultimately concerned with words, “even when it becomes involved with ideologies” (57). Setting aside the now-obvious observation that it was always also concerned with ideologies, we need not be as quick as he was to delimit the method. If “historical criteria” can be observed by taking seriously the words of revolutionaries, surely their adaptability could rub off on historians, too?

Elleni Centime Zeleke and Arash Davari ask this question in their provocation on the “third world historical” (also see work on “third world historical” on the site Borderlines). In the introduction to their 2022 co-edited volume on the same concept, Zeleke and Davari offer a “bridge across different sites of national history” and ask what changes when historians take the Ethiopian and Iranian revolutions as “world historical”. Through Biodun Jeyifo’s concept of “the whale” (2002) and Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History” (1940), the framework of the “third world historical” emerges as an epistemology and a rejection of a false choice. Just as Benjamin “refuses the bargain of liberalism or fascism,” Zeleke and Davari reject the opposition postulated by social scientists between liberal democracy and authoritarianism (424). Instead, they invite us to consider what “impossible conditions” were swallowed up by postcolonial states, invoking Frantz Fanon’s contention that “the apotheosis of independence becomes the curse of independence” (426; from “On Violence,” 54). Even as Koselleck named states where “civil wars” were raging, it is the “diverse group of countries” that claimed “world revolution” that prevented the “occasionally concrete” meaning of revolution from co-existing with this multitude. Zeleke and Davari ask, “is the state the only way to hold political community in the third world?” (424). In their project, time and experience are central: essays include Taushif Kara on intezar (waiting), Amsale Alemu on Ethiopian students’ project of “demystification,” and Naghmeh Sohrabi on “writing revolution as if women mattered.”

The experience of participating in a “historically recurrent convulsive experience” (Koselleck, “Historical Criteria,” 50) ordered by the echoes of Revolution but under entirely new conditions demands its own concepts, as Bassem Saad writes on how names and figures of the dead in today’s uprisings work to “export the revolution.” In memory of Mahsa [Jîna] Amini, Mohamed Bouazizi, and Sarah Hegazi, Saad writes that the “historian of the immediate” is charged with capturing those forms and figures which might evade conceptualization if the inside of the riot is not accounted for, “if we wait long enough for the books.” Querying the insides would hinge on the epistemology of revolution, with the time-space inside an uprising telling us more than an observer’s could. Koselleck’s concept of revolution is itself a historical artefact.

At best, it is an oversight—or “pessimism,” as Harcourt puts it. At worst, it is the symptom of an incomplete “denazification” that fit comfortably with a broader Cold War liberalism, in which the dividing line between civilized and savage also divided “revolutions” from mere squabbles. Either way, one does not need to look too closely to observe the tensions holding together a still-influential method of intellectual history. Both historians and revolutionaries agree: it is vital to understand how revolutions can be made, experienced, unmade, and if, at all, they might succeed. But why would a historian even want “historical criteria” to identify and categorize the concept? Most might say: “to understand revolutions.” The query is fundamentally different when the answer is instead: “to make revolution.”

Disha Karnad Jani is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Research Training Group “World Politics” at Universität Bielefeld. She received a joint PhD in History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University. Her current book project is an intellectual history of the League Against Imperialism (1927–1937). She co-hosts the podcast In Theory for the Journal of the History of Ideas Blog.

Edited by Jonathon Catlin

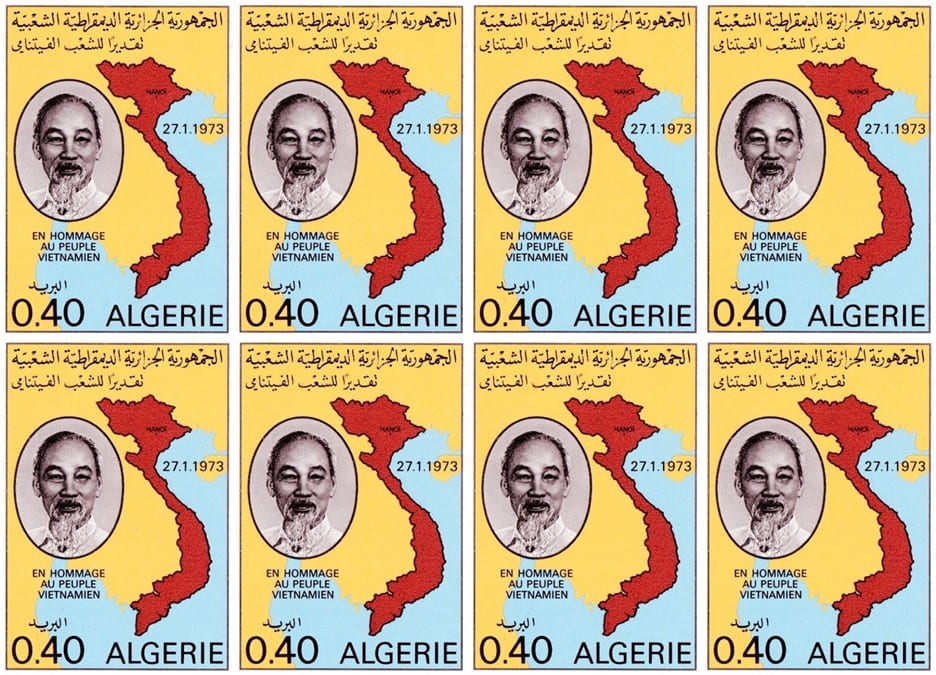

Featured Image: Tiled image of a 1973 stamp from Algeria in honour of the Vietnamese people.