by Alexander Collin

Alexandre Roberts is a Byzantinist, Graeco-Arabist, and intellectual historian. He is Associate Professor of Classics and History at the University of Southern California. Currently, he is working on a monograph entitled Chemistry and Its Consequences in Byzantium and the Islamic World. His first book, Reason and Revelation in Byzantine Antioch (2020), was on the eleventh-century scholar Abdallah ibn al-Fadl of Antioch as a window onto engagement with ancient Greek, Byzantine, and Islamicate thought during the pivotal century of Byzantine rule over Northern Syria.

He spoke with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article, “Thinking about Chemistry in Byzantium and the Islamic World” (volume 84, issue 4).

Alexander Collin: Let’s start with some general context, your article focuses on chemistry in both the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic world. Do you see those two regions as having distinct traditions of chemical knowledge or is it something they share?

Alexandre Roberts: They certainly go back to a shared tradition, but the question of what their interrelationship is in the Middle Ages, even the early Middle Ages, is totally open. There is a murky early period in Islamic alchemy that we really know very little about. A key figure in this early period is Jabir ibn Hayyan, who is supposed to have lived in the eighth century, but there is no consensus among scholars about whether such a person ever existed.

However we date the texts ascribed to him, we have to ask how they might be related to the roughly contemporary early medieval Greek material, if at all. In Greek, that early medieval period is still waiting for us to begin to explore it, really, because the relatively few scholars who have worked on Greek alchemy have tended to focus on the earlier material that survives.

AC: One of the things the Greek and Islamic traditions do share is a grounding in Aristotle’s chemical thinking. Could you give a quick sketch of the chemistry of Aristotle?

AR: Aristotle’s classification of minerals and theory of mixture are the places to look. In Meteorology, Book Four, there is a discussion of how minerals are formed under the earth. Aristotle discusses how one should approach the classification of minerals and their properties: are they malleable? Are they fusible? Are they friable? He classifies them based on these kinds of criteria and discusses how he imagines them being formed under the earth.

Meanwhile, his treatise on Coming-to-Be and Passing Away offers something like a theory of chemistry—or what I’m calling chemistry, which is to say, what happens when you mix things? How do ingredients combine to produce something new? What he asks us to imagine is that both initial ingredients continue to exist in the new mixture only in potentiality, not in actuality, and could in theory be extracted from the mixture again. He calls the result of this kind of mixture “homeomerous,” a term that describes something whose every part is like all of its other parts.

In certain key ways, that is very different from modern chemistry. In the modern view, if you look closely enough at a mixture you can still identify the different atoms that it is made of. Whereas, for Aristotle, no matter how close you get, you will always get that same new mixture. Blood is one of his examples. So, no matter how closely you examine a sample of blood, according to Aristotle, you won’t find a place where you have some of ingredient A next to some of ingredient B. You just have blood.

AC: I’d like to stay with the question of materials a little longer. There are certain materials—gold, lead, mercury and so on—that recur both in the historical texts and in modern scholarship on alchemy. Is there something, either materially or culturally, that makes those materials so central to medieval chemistry?

AR: My sense is what we’re looking at here is a set of particularly anomalous examples—anomalies from the perspective of the Aristotelian theory—where artisans can make these minerals transform in really weird ways. If they change colour, for example, or go through some other change that can’t be determined by the linear addition of qualities that one would expect from Aristotle’s theory, then this phenomenon calls out for explanation.

Aristotle claims that the four elements each have two of the four primary qualities hot, cold, dry, and wet. When you mix them, the proportion of primary qualities determines the properties of the mixture. And that doesn’t really hold up when you encounter these nonlinear jumps to properties that can’t obviously be analysed in terms of the two-dimensional hot/cold and dry/wet spectrum. So, for that reason, I think it’s something that not only interested people who worked closely with these minerals, whether at an imperial mint or in other metallurgical contexts; it also engages theorists.

This is why I think someone like Ibn Sīnā is interested in weighing in on the matter, because here we have something that calls out for further explanation. That’s part of what the article is trying to reframe. You can look at these texts not so much to understand who’s for and against “alchemy,” but rather to reconstruct a debate about how to explain phenomena that can be observed in metal-working and other applied chemistry.

AC: I’m interested in what that change in perspective does to the conventional idea of alchemy. We have a stereotypical picture in which chrysopoeia is absolutely central to the whole enterprise. Do you see this new interpretation affecting the centrality of chrysopoeia to this branch of knowledge?

AR: To answer that, let me distinguish between chemistry as a topic, on the one hand, and one particular textual tradition interested in this topic, on the other. Regarding chemistry as topic, we can look back and see people discussing what I would call chemistry, discussing the transformation of matter in one way or another. On the other hand, there is a textual tradition that is recognizable because it cites a particular set of authors in Greek (and a different but overlapping set of authors in Arabic) and because texts in that tradition often say they are about the “Sacred Art” or simply “the Art.”

The modern notion of “alchemy” typically conflates that tradition with recipes for various manipulations from the broader chemical literature, even though they are largely divorced from this textual lineage on the Sacred Art. That’s how I came to think we need a name for this tradition, what I have referred to as the hierotechnical tradition. I don’t know if anybody else will like the name, but at least it gets us away from the baggage of “alchemy.”

So, to get to your question: I wouldn’t claim that the hierotechnical tradition is uninterested in gold or less interested in gold than we thought. Chrysopoeia is a central aspect of this tradition that describes itself as being about the Sacred Art. It doesn’t seem to be the exclusive thing (for example, in the early texts there is a greater variety of recipes and more focus on purple dyes and other materials), but it is undoubtedly a central concern for the tradition, not just how to make gold but also how to interpret gold-making.

But if we try to decouple chemistry as a topic from that hierotechnical tradition, then we can look and say, well, there’s more to chemical thought than what we find in the hierotechnical tradition. We need to look in a wide variety of recipes (for food, drugs, perfume, ink, and so on), in the natural philosophical tradition, and in the medical tradition, and compare that to what we find in the hierotechnical tradition.

So, if you define our modern term “alchemy” as the hierotechnical tradition, then it was largely about chrysopoeia. But if you define “alchemy” as anything premodern having to do with chemistry (as a topic), then chrysopoeia was only a small part of it.

AC: I want to ask you what feels like a dumb alchemy question, but also maybe an important one. Recipes are central to medieval chemistry and a lot of them work: If you give me a recipe and I follow the recipe well, I can get a material that has a certain weight, or malleability or whatever property I’m looking for. But if you give me a recipe for turning base material into gold, I never get gold.

How do the people participating in this project manage that sense of, I suppose, disappointment with chrysopoeia? How do they keep this debate going over the centuries as they try new recipes and find again and again that it doesn’t produce results in the way that their recipes for perfumes or alloys do?

AR: Yeah, it’s a persistent question. It’s often been asked with the implicit message of, how could they be so dumb, how do they live with this cognitive dissonance? To answer that, I would start with A. J. Hopkins, who was writing in the early twentieth century; I don’t agree with everything he wrote, but in struggling against the presentist framework of the history of science as practiced in his day, he was clearly onto something.

What Hopkins said is, look, we have to understand that the ancient Egyptians and Greeks had a totally different way of conceptualizing matter, they didn’t have our periodic table of elements. So, when they said gold, they meant something that had the observable properties of gold, and what they were trying to do is get closer and closer to approximating those properties.

The way they talk about this in the Aristotelian tradition is in terms of “essential accidents,” meaning properties or qualities that are essential to what something is. What makes gold gold and not something else? It was pretty typical to identify distinctive perceptible qualities of metals and other materials with their essential accidents.

It’s intuitive, in a way. If you think of baking (to adapt Kit Fine’s example used in a different context), when you make something that smells and looks and tastes like bread, then that’s bread, right? There’s not some deeper, hidden essence to it. Maybe Fine’s example, butter, works even better in this context too: if it tastes and feels and looks and melts just like butter, then it is, for the baker’s purposes, butter.

So, when chrysopoeians make something that is just like gold or silver, they think that they’ve done it. The theoretical debate is then over how best to interpret this outcome; have they really done it, or is there some hidden property that in fact makes gold gold, without which you just have something that very precisely imitates gold?

AC: So, it’s less static than it perhaps appears from a modern perspective, because they are making these steps and thinking “yes, we’ve managed to get our material to have some of the right accidents, we’re getting closer.”

AR: Exactly. We want it to be yellow, we want it to be malleable, etc. etc. And yes, we can look back and say, they don’t realise that you need a particle accelerator to make gold out of something that’s not gold. But why should they?

AC: Well, thank you for a smart answer to a dumb question. Let’s pivot to look a little more at the people who are engaged in this kind of work. One of the themes that runs through the four authors that you discuss in the article is that they talk about “tricksters” or “those who use artifice.” Who are these people? Is it just a rhetorical device or is there a real group to whom they’re referring?

AR: Historians have often presumed that we already know the answer, but it’s actually not clear. This is a question that we can answer only if we start again from the texts, and even then, we should be very cautious when dealing with these periods for which relatively little evidence survives. Tara Nummedal produced a wonderful study addressing in part more-or-less this question for the Holy Roman Empire. She looked at archives and court cases and various documentary evidence about people who were making gold or similar things, often getting in trouble for it. I don’t think that this kind of granular detail is possible for the period I’m looking at, but we can still ask the question.

I would say, first of all, we have to be very careful even with the words. When Ibn Sīnā uses the term ḥiyal to talk about artifice, well, there’s a whole science of ḥiyal, which is about mechanical devices. In that sense ḥiyal refers to a legitimate discipline, but it can also apply to tricksters. So, is he saying that he thinks only tricksters are using impure sulphur? Or is he just saying nobody who’s in the business of making these artificial materials is going to have access to pure materials, whatever their intentions or their status? In other words, is he talking about artificers or deceitful artificers?

Or consider Ibn Taymiyyah, the jurist who issues the fatwa against kīmiyāʾ that I discuss. He describes at length a debate he had with someone who thought that kīmiyāʾ was legal and who tries to argue, in Ibn Taymiyyah’s telling, that good, reputable Muslims have practiced it too. But Ibn Taymiyyah rejects that claim and instead tries to associate kīmiyāʾ with sīmiyā, which is a term for a type of magic or sorcery. So, we have two competing images of the practitioners of kīmiyāʾ. How do we know which image to believe?

If we look at the case of Psellos and his accusation against Patriarch Keroularios, the picture is different again. The accusation is partly about reading hierotechnical texts but in the end is really about using gold outside of the structures imposed by the imperial fisc and imperial law. This is a Patriarch—an extremely powerful person in the eleventh century—defying the emperor by encroaching on a legally sanctioned imperial monopoly. This certainly isn’t our image of alchemists in their dingy basements.

AC: Right, this is also something I wanted to ask about. To what extent is there something you might call a class dimension? Metalworking is dirty, it’s somewhat dangerous, you’re digging stuff out of the ground; is there a sense that these writers are shut away in their studies and libraries and mistrust chemistry for that reason? They see it as un-gentlemanly to put it anachronistically?

AR: That is certainly something you see in the historiography. Some people do take the view that a lot of these texts are divorced from laboratory practice. But there are some early modernists who have tried to test this, I’m thinking of Lawrence Principe, William Newman, and Pamela Smith in particular, along with Matteo Martelli, a historian of Greek alchemy and related traditions. They have gone to chemistry labs and often collaborated with chemists to try to reproduce some of these recipes. “Laboratory philology”— it’s a way of interpreting the text, testing out different interpretations and seeing if they work. And they’ve typically found that these recipes do work, at least for the small number of cases where this has been tried. So, we’re probably not talking about texts that are totally divorced from practice.

Ibn Sīnā himself seems to suggest he’s been present when meteorites were probed, and he makes other references to empirical phenomena. And certain hierotechnical authors like al-Jildakī make more references to practical experience. On the other hand, I think there are writers who better fit that ivory-tower model, even if you can’t rule out the possibility that they engaged in laboratory work. Psellos is a little like that. His literary production suggests somebody who’s very bookish and more interested in the philosophical side of these issues. He certainly seems to build his ideas mainly from his reading. But, again, it doesn’t rule out his involvement in laboratory work.

So, there’s certainly no hard line between elite learning and lab work in this period. Still, something of that class idea persists. Whenever you see people like al-Fārābī saying there are people doing this for the right reasons, and others who are not, I suspect there is something class-based going on there. Kīmiyāʾ is not grouped among the very lowly trades like dung scoopers but I do think you’re right to say that there are people who are just metallurgists, who are not engaged in the whole theoretical debate, even if they have their own understanding of what is going on. Whether there is an elite counterpart, people who are totally divorced from the actual metalworking, I don’t know.

AC: Who is the audience for this hierotechnical literature and for all the work critiquing it? Where does the impetus come from to create these texts?

AR: There’s a lot of variation between the different authors. Among the authors I discuss in the article, al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā are perhaps the most similar, they’re both philosophers in the Aristotelian tradition with an interest in natural philosophical questions. For al-Fārābī, certainly in the treatise—he frames his work on kīmiyāʾ as a philosophical attempt to understand material transformations. Likewise, for Ibn Sīnā, it’s in the context of his philosophical summa that this passage on chemistry comes, as he’s working through a whole range of Aristotelian ideas.

But then when you get to Ibn Taymiyyah, things look a little different. His work has specifically been commissioned, as every fatwa is, and I think then you have to ask who wanted to know if this is permitted. Presumably there are lots of people making and selling goods that are artificial, often very openly. As in: do you want to buy the real salt or ambergris or whatever, or do you want to buy this cheaper artificial stuff? Same for perfume and so on. But a lot of money is involved, so people can get really worked up about how exactly one should regulate them. In that context, you can imagine somebody wanting to know, is this even legal? Is this permitted according to the divine law?

In the end, there is a range of motivations. Ibn Taymiyyah writes his fatwa against alchemy because it is commissioned, but he is also interested in the philosophical question, and he refers to philosophers in his text. So, you have an intellectual motivation, and you have your day-to-day market regulation, juxtaposed in a single text.

AC: Are these alchemical questions seen as big philosophical issues in this period; is this something you have to have an opinion about if you’re a prominent intellectual? When someone like Ibn Taymiyyah is commissioned to write a fatwa about alchemy, is it an issue where he would say, yes of course I have a position on this, or is it something more niche that he might not have thought much about?

AR: I wouldn’t say everybody feels like they need to weigh in, but if you were interested in legal or philosophical controversies, that might easily lead you to this subject. It’s not central; it’s not any kind of key to the thought of someone like Ibn Taymiyyah in a general sense. But lots of writers do feel somehow drawn to weigh in.

I think for Ibn Taymiyyah, you can see him working from a set of sources, different legal authorities, but his starting point is actually almost a theoretical one. For him, there’s stuff that God creates and there’s stuff that human beings create, and there’s just no overlap. To me this reads like he had a sort of dossier ready to go on this topic, but maybe I’m wrong.

This question of scholars weighing in and often “condemning alchemy” is actually where I started with this article. I went to write it because I was interested in the pro and contra alchemy lists that medieval and modern scholars have compiled. Manfred Ullmann studied this in the 1970s. He published a book, Die Natur- und Geheimwissenschaften im Islam, that includes a brief chronological account of the authors who were for and against alchemy. Al-Kindi weighs in and he says no to “alchemy.” Then al-Fārābī weighs in and he says yes. Then Ibn Sīnā, and he says no.

I’m giving a schematic and simplified picture of Ullmann’s account, of course, but this is what such accounts boil down to: a series of people weighing in on two different sides, for and against. That’s why I wanted to read some of them more closely and look at the nuances of what they are saying and why they’re saying it. What, exactly, were they for or against?

AC: Thank you. In closing I’d like to ask about your upcoming projects and publications. Is there anything readers should be looking out for?

AR: I’ve been working on something I have been calling “Disentangling Alchemy”—I began giving a series of talks sketching the idea a year or two ago. The idea is to ask, well, if I think alchemy is such a misleading term what terminology should we be using? What should we take as our starting point?

If you look at twentieth-century attempts to define alchemy, a lot of them come down to either narrowing it to what a particular group at a particular time was doing, or focusing on the modern use of the word alchemy and correlating it with terms used in the past. For the latter approach, one typically looks for words that looks like “alchemy” like Latin alchimia, Arabic al-kīmiyāʾ, and Greek chymeia. But this back-projection of the modern term quickly gets very misleading.

One of the aims of “Disentangling Alchemy” is to say, well, what are we actually interested in here? On the one hand, we have this topic—what I call chemistry, meaning the theory and practice of the transformation of matter. In that case we’re interested in anybody who has something to say about this topic. On the other hand, we can also investigate a certain textual tradition—what I’ve been calling the hierotechnical tradition. How is that tradition formed, who is contributing when, and how does the tradition develop and branch over time?

Of course, I am not alone in this. If you look at Jennifer Rampling’s book on English alchemy, it’s a very sensitive reading of a lot of these issues. She discusses the “practical exegesis,” as she calls it, employed by early modern thinkers in England trying to read texts on gold-making and the like that they don’t fully understand with the help of laboratory work. In this and in the rest of her book, she is attentive to the dynamics of a textual tradition and to the intellectual developments that one can trace through those texts.

Still, we need to think more about how the different things that we group under the umbrella term “alchemy” interrelate. My ultimate aim in this series of projects on chemistry and the hierotechnical tradition is to show that the surviving evidence for metallurgy, the Sacred Art, and various ways of thinking about chemistry is not some strange aberration or anomaly in human history to be read only by eccentric specialists and kept at arm’s length by everyone else.

Anyone interested in the history of chemistry has a stake in this material, as does anyone interested in the cultures that produced these texts and these thinkers. To interest all those readers, though, we need to integrate these texts and these ideas into the story of chemistry and of intellectual history writ large. This will let the surviving texts be seen for what they are: fascinating glimpses of how those who came before us made sense of the world around them. Chemical theories from the past remind us that there have been many ways of reading the book of nature just as plausible as our own, and that there may yet be new readings to come.

Alexander Collin is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam where he works on northern Europe from the 1490s to the 1700s. His doctoral thesis aims to test the historical applicability of theories of decision making from economics and organizational studies, considering to what extent we should historicize the idea of “The Decision” and to what extent it is a human universal. The project has been funded by the Leverhulme Trust and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst. Alexander has written for The Historian magazine, Shells and Pebbles, The History of Knowledge Blog, as well as academic publications. Alongside his historical work, he also contributes reports to the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. He studied at King’s College London, Humboldt University Berlin, the University of Cambridge, and Viadrina University Frankfurt.

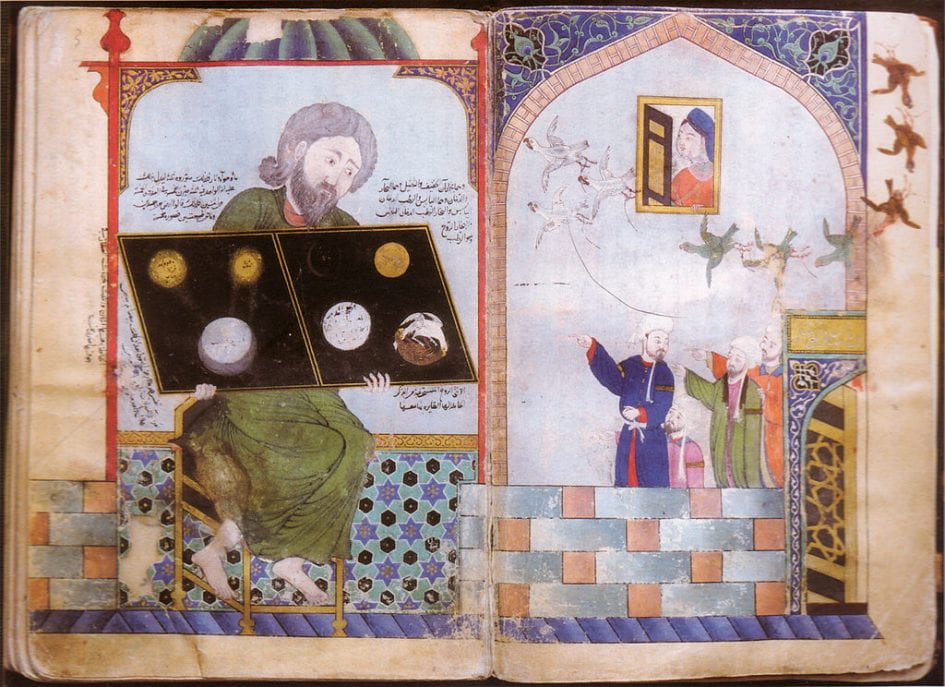

Featured image: Illustration from a transcript of Muhammed ibn Umail al-Tamimi’s book Al-mâ’ al-waraqî (The Silvery Water), also called Senioris Zadith tabula chymica, Topkapı Palace collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.