by Jonathon Catlin

Samuel Clowes Huneke is a historian of modern Europe and Assistant Professor of History at George Mason University. His award-winning first book, States of Liberation: Gay Men between Dictatorship and Democracy in Cold War Germany (University of Toronto Press, 2022), comparatively examines gay persecution and liberation in the two Germanies during the Cold War. His latest book, A Queer Theory of the State (published in 2023 by Floating Opera Press and distributed by Columbia University Press), grew out of a 2022 essay for The Point. It asks how queer theory can wed its critically anti-normative impulses to the empirical need for a state. In answering this question, Huneke argues that the state is an integral component of a politics that seeks to subvert and undo the oppression of queer lives. Contributing editor Jonathon Catlin interviewed Huneke about his new work.

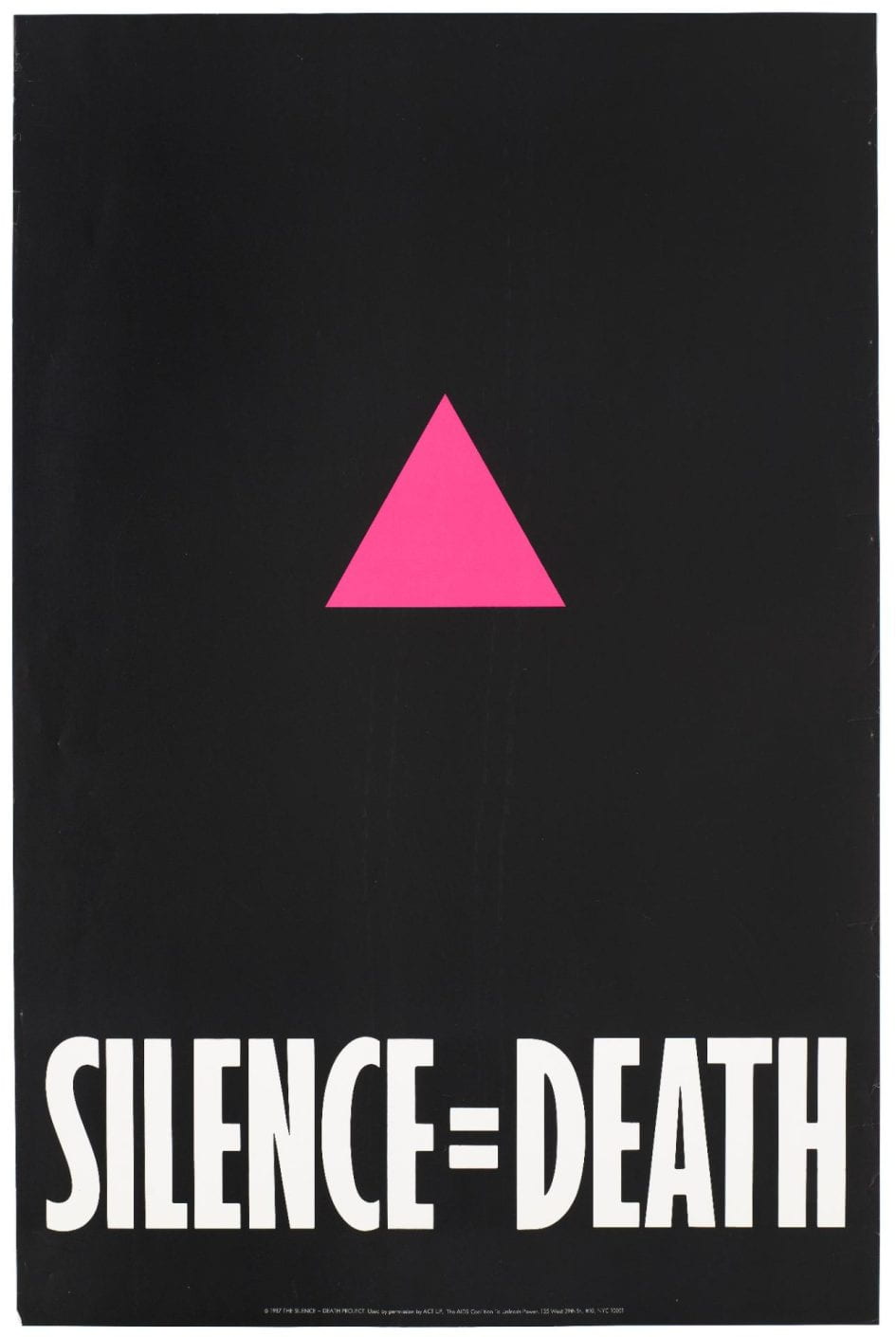

Jonathon Catlin: You and I began corresponding in 2020 during the heyday of the COVID-19 pandemic, when queer responses to the AIDS Crisis sprung up as a “usable past” for addressing COVID-19. We got in touch again during the mpox (a.k.a. monkeypox) epidemic, which swept across predominantly gay male communities in summer 2022. Through the fluke of getting photographed in the right place and time at a rally for action on mpox, I ended up becoming a “poster boy” for the kind of demand for state intervention that ACT UP had demanded a generation earlier: for state governments and health agencies to recognize queer disease and suffering as a health crisis, and to respond accordingly by provisioning vaccines and other treatment at scale. “Disease,” you write in the book’s opening line, “has a way of clarifying things” (11). Such events serve as “Rorschach tests” for politics as usual (14). Let’s start with how these crises illuminated and sharpened the central question about the ambivalent role of the state in queer politics.

Samuel Clowes Huneke: The mpox epidemic that swept the country in 2022 was a formative experience for how I’ve come to think about the state. It also, as you mention, served as a kind of Rorschach test for how queer intellectuals and activists view the state. I think here the ambivalent approach to the state is actually at its clearest. The Biden administration was, frankly, incompetent in how it handled the disease. This was a disease that we were already familiar with. It’s remarkably similar to smallpox, which, of course, was the only infectious disease to have been successfully eradicated. But the administration waffled and, prevaricated. Reluctant to buy vaccines in sufficient quantities, it allowed doses of the vaccine it already owned to expire. To my mind, the clearest sign of its ambivalent approach was its long-term reluctance to specify who was most at risk. We in the queer community knew that it was primarily queer men, with the disease seeming to spread through sexual contact, although it is not, strictly speaking, an STI.

There were two very different responses from both queer activists and queer intellectuals regarding this incompetence. On the one hand, many saw the administration’s inadequate response as a sign of malicious neglect and the state’s desire to harm its queer populations. On the other hand, there were those who looked at what the administration wound up doing, namely distributing sufficient doses of the vaccine to more or less stamp out the virus in this country arguing that this was a successful state intervention in public health. I’m less interested in who’s right or wrong here and more interested in the fact that two different—but allied—groups of intellectuals and activists drew radically different conclusions from the same experience.

To my mind, COVID-19 offers a different and much less ambiguous mirror. Casting our minds back to spring 2020, I think most of us on the left were, in fact, calling for state intervention to limit or prevent the spread of this novel virus. A frightening time, most of us were passionate about having a state that would fund research into vaccines, tell us how to behave in order to limit the spread of the virus, and take public health measures to enforce those behaviors. I was really struck at the time by the way that the Foucauldian lens through which many academics view the state fell rapidly away in those months. Taking massive public health measures to ensure the health of a population is precisely what Michel Foucault meant by biopolitics, and yet very few academics were using that term to describe state responses to COVID-19, precisely because they were in favor of those responses. They largely weren’t interested in criticizing these policies in the way that Foucault critiques the biopolitical measures of modern states—at least implicitly.

The one exception, of course, was Giorgio Agamben who seemed to lose his head entirely and argued that prophylactic measures were a kind of new totalitarianism. But most intellectuals rejected this line of thinking. At the time of COVID-19, which is really the moment when I first started to conceive of this essay, it struck me that there was a profound disconnect between massive state-based interventions that ultimately proved highly successful when it came to mpox and at least partially successful with COVID-19 and the ability of queer critique to grasp the state as anything other than a locus of violence. At the same time, the subsequent backlash to COVID-19 measures, which largely came not from the radical left but rather from the far right, highlights the real distrust with which so many citizens, after decades of neoliberal policymaking, regard our government and the power of the state.

JC: The pioneering queer theorists of the 1990s and 2000s contended that queerness should be a source of resistance to normativity. I could relate so much to your description of rapt attention and intellectual wonder upon first reading Foucault and his successors such as Michael Warner, Leo Bersani, and Lee Edelman. Yet already in the 1990s some queer critics like Lisa Duggan began to tire of this “Foucauldian hangover” (68): Yes, critique of the state is essential, but don’t we also want the state to do things for us? Bruno Latour and Rita Felski have similarly argued that other fields of critique have “run out of steam.” You write in significant agreement, “Much of queer theory suffers… from an inability to think constructively, hamstrung by reflexive critique” (15).

SH: I don’t think I’m necessarily original in raising these concerns. Decades ago, as you point out, in queer theory’s heyday, Lisa Duggan wrote about the political quiescence of certain strands of queer theory. Their practitioners often marketed themselves as the cutting edge of scholarship and activism, but all too often rejected any sort of political action that might make concrete differences in queer peoples’ lives. Heather Love recently wrote a scathing critique of queer theory’s inability to make a meaningful impact on the world, in part because it rejects empiricism. Christopher Chitty, too, offers a rebuttal of the traditional canon of queer theory. For him, it’s less resistance to empiricism and more its bourgeois class affinities that limit the field’s political utility. Where I think I’m adding something is in bringing this conversation specifically to conceptions of the state. I’m trying to work out what exactly queer theorists think about the state and why. The ultimate goal is not simply to offer up a critique of critique, which is certainly one of the flaws in some of the works you mention, but rather to think constructively and imagine a queer state, and how we might reconcile the empirical need for state action with the profoundly anti-normative and often anti-empiricist impulses within queer theory.

JC: Similarly, you observe that those fore-figures of queer theory were largely trained and housed in literature departments. This explains not only their often abstruse “pomo” writing styles, but also the remove of their work from empirical political and historical realities. What new perspective do you bring to this question as a historian working on the history of gay men in Germany (in your first book) and queer women in the Third Reich (in your second book in progress)? I think your historical approach comes through in your lucid writing style, but does it also concretize or differently reframe this issue in a more pragmatic direction?

SH: Oh, absolutely. There is a longstanding antagonism between empirical and interpretive fields allied under the umbrella of queer studies or queer theory. For a long time and perhaps even still today, the interpretive fields were the ones which enjoyed preeminence. At the same time, these critiques about the lack of empiricism in pure queer theory are nothing new. Duggan once wrote that “the impressive expansion of increasingly sophisticated analysis” within the field was “balanced precariously atop a stunted archive” (181). Then, she adds a scathing aside about how we don’t need yet another article on Gertrude Stein.

One trait that really connects most historians is a basic fidelity to empirical evidence. We start with research questions about the past and go looking for archives to answer them. We don’t let theory dictate our evidence or our conclusions. At the same time, many queer theorists exhibit a profound hostility to empiricism. In many cases, this hostility originates from a distrust of the hard and social sciences, which historically have employed empirical evidence to denigrate and, sometimes, even try to exterminate queer life. Ultimately, this hostility to empiricism is part of why many queer theorists reject the state.

From my own research into the queer history of twentieth-century Germany, I see a far more ambivalent and heterogeneous relationship between states and queer people, exhibiting what Paisley Currah, in particular, has characterized as the multifarious nature and nearly infinite complexity of modern states. I see this in how queer women evaded police detection in Nazi Germany or, in some cases, even turned bureaucrats’ own paranoias against them. I see it in the ways that East German gay and lesbian activists were ultimately able to work with the communist dictatorship and to persuade its functionaries to promulgate some of the most sweeping pro-gay and lesbian reforms that the country had ever seen.

JC: The time seems ripe for developing a positive role for a stronger state to advance the interests of queer people now that we have become acutely aware of the hazards of how one-sided “queer anti-statism” and “anarcho-libertarianism” can play into neoliberalism. The pragmatic institutionalism you advocate isn’t all that sexy, you confess. It’s sort of boring to say: Sometimes (like during a pandemic) we need the progressive state and it can do good things for us. Is that one of the reasons it hasn’t received much attention in queer politics? Has the intellectual and creative self-fashioning of queers as dissidents also held them back theoretically and politically?

SH: Surely. I have to say, I am always suspicious of scholars who seem more enamored with the aesthetics of academia than with the actual work. Similarly, I’m skeptical of radical activists more interested in fashioning themselves as such than actually trying to make life better. It’s not very sexy to say: Listen, we sometimes need to work with the state. In their foundational article, “What Does Queer Theory Teach Us About X,” Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner observe (approvingly) that queer theory has flourished in fields foreign to the kind of expert knowledge on which states rely. Many queer theorists remain proud of their lack of utility to the state.

But when you’re more interested in playing the part of a radical than actually accomplishing something radical you get scandals like the one surrounding Avital Ronell in 2018. After Ronell was accused of sexually harassing a graduate student, famous queer theorists rushed to her defense. Heather Love has noted that queer theorists, especially star queer theorists, have lost sight of the fact that they are “superordinates” within the university system (87). That is, even if they perceive themselves as radical outsiders—or “underdogs”—they remain insiders who wield considerable influence. Certain thinkers whose work advances a kind of anarcho-libertarianism have perhaps forgotten that they enjoy the privileges of a large salary, secure job, and prestigious title.

JC: You characterize the state not as a monolithic source of domination but rather as a jumble of competing and conflicting interests and functions that’s shot through (per Foucault) with both power and resistance. Although probably familiar to all historians, you point out the idea is also rather queer! Your pragmatic conception of the state, which embraces its “messy ambiguity” (50), leads to your provocative conclusion: “Democracy may be—in fact is—imperfect, but it is the queerest form of government yet invented. […] It is the kind of government most capable of adjusting queerly, of self-reflexively adapting to the problems of the present” (65). A “non-cynical” form of constructive critique, you suggest, would channel queer demands into new norms and implement them in state institutions—through outside protest and inside work. What’s your response to critics who might say: Just look at history; when queer demands get taken up into the state they always end up coopted and deradicalized?

SH: I have a fundamentally Hegelian view of history: history advances dialectically. It moves in stages that are not linear but iterative. You might have progress in one arena and revanchism in another. Never neat and always through conflict, progress begets backlash, and regress begets its own progressive backlash. It only ever, I fear, feels incomplete to those who live through it. But part of my commitment to empirical reasoning is to actually look at queer movements in the past and see where they have succeeded and how as well as where they failed and how. Starting with actual experiences rather than a theory that dictates what’s right and what’s wrong, what’s progressive and what’s not.

If we look at the debate over marriage equality, we see how marriage can coopt queerness into a kind of domesticated normativity. And that is precisely what figures like Andrew Sullivan wanted when they suggested marriage equality as a national agenda. This is also why conservative lawyers argue cases in front of the U.S. Supreme Court that a right to marriage is to be found in the American Constitution. But if we actually look at what marriage equality has done over the past decade or so, it has not, by and large, evacuated queerness of its radical potential. At the same time, it has ameliorated the often-dire circumstances of queer people in this country. This is not to say that we live in a queer-friendly country by any means. The moral panic that we are now experiencing belies any such notion. But by any measure, the lives of queer people today in the U.S. are better than they were two decades ago, and I credit marriage equality and associated drives for state recognition with much of that shift. All this is to say that marriage equality was never the end goal for many who push it, but rather a first initiative that might open the state up to the possibility that queerness could exist not on the exterior of society but rather within its very interior. By granting access to these rights that are fundamental to our society, we might make ourselves better, more progressive, and even grasp at the utopian horizon of queerness.

I argue in the book that democracy is the queerest form of the state. But that doesn’t mean it’s queer as currently constituted. I think we all accept that liberal democracy in its present iteration is based on a stultifying kind of individualism. What I argue for instead is a queer democracy that takes its basis in communitarianism, in the insight of queer theory—and here I’m drawing in particular from the work of Judith Butler—that we are not monadic individuals but rather social beings who only ever exist and exercise agency in the context of other social beings. Hence democracy should not be about repelling one against another in a minimal state, but about acknowledging and fulfilling our obligations and duties to each other. My plea for a queer form of democracy is far from a call to accept the status quo. Rather, it’s to say that we need a radical queer politics that embraces state power on a democratic basis rather than rejecting it out of hand. In my view, a blanket rejection of state power is what paves the way to both neoliberalism and to the persecuting societies of fascism.

JC: You’ve also written about the notion of “queer citizenship” and have edited a forthcoming volume on citizenship in contemporary Europe. After grappling with the intersections of formal law and participatory politics on the one hand, and subjectivity and belonging on the other, I’m curious how you assess the limits of “identity” as a basis for politics. You nod to well-known criticisms from both the right and left of “identity politics,” but don’t seem wholly convinced by alternatives that would posit in its place, say, national belonging or universal solidarity. You observe in an essay from 2019 that—with the interesting exception of the U.S.—“gay men were, on average, more likely than the general electorate to support the conservative or far-right party.” The AfD in Germany, for example, has a prominent lesbian figurehead but maligns migrants as hostile to the LGBTQ+. So, what’s left of queer identity politics?

SH: I see queerness as more than an identity and also more than a narrow project just for LGBTQ+ people. Rather, it’s about deconstructing and opposing norms, prejudices, and violence on the basis of sex, sexuality, and gender. It’s a project that affects every human being. Since recorded history, we know that states and societies have policed these things and that these are, in fact, a fundamental part of what make us human and of what make us social beings. Queer theory is really an intellectual and political project that, at its best, offers a form of liberation to everyone.

As a result, I’m skeptical about what “identity” can do for us in the long term. That doesn’t mean that I reject automatically that identity has a role to play in the contemporary Left. Identity is important in shaping and informing our politics. It’s clear to me that identity-based discrimination very much persists in our world. In these instances, then, identity-based activism is a necessary corrective for channeling progressive politics and carving cultural ruts through which it can flow. But, ultimately, progress will only ever be successful through a politics that takes seriously identity-based discrimination but does not remain bound by it—finding elective affinities which cut across and through identity.

JC: You’ve written popular essays about disturbing historical parallels for contemporary culture war panics about queer and trans people “grooming” children (surprise: the Nazis did that, too!) and rollbacks to life-saving gender-affirming care. The stakes of issues surrounding gender identity today often seem life or death. What role can the “muscular” state you argue for play in addressing such divisive culture-war issues?

SH: The state needs to be doing more, not just for queer people but for everyone. I’ve spent much of my short career thinking about and trying to understand when, how, and why queer minorities become scapegoated. It’s clear to me that it often happens in periods when rulers and elites try to consolidate their authority as well as in moments of economic or social uncertainty. Obviously, these two phenomena go together, hand-in-glove.

In the immediate term, there is a role for the state to protect vulnerable populations—in this context, queer and especially trans people—from forms of persecution and harassment. That means stepping in to prevent rollbacks of gender affirming care. It means ensuring that municipalities are not banning books. It means making sure that teachers aren’t being fired for their gender or sexual identities. But it also means that the state needs to better address underlying iniquities. We need to ensure that everyone has access to health care, that our schools are well funded, that our teachers are adequately supported, that roads are maintained, that public transportation is developed, that everyone can breathe clean air and drink clean water. That is the role the state has to play and that it has methodically abdicated over the last half century. Only when we take joy not only in our own ability to access these goods, but also in the ability of our neighbor to do so will we have started down the path to a queer state.

Jonathon Catlin is a Postdoctoral Associate in the Humanities Center at the University of Rochester. He earned his PhD in History and Interdisciplinary Humanities from Princeton University with a dissertation on the concept of catastrophe in twentieth-century European thought. He has written and edited for the JHI Blog since 2016. He tweets @planetdenken.

Edited by Jacob Saliba

Featured image: 1987 poster created by the Silence=Death Project, an affiliate of ACT UP in New York City. Wikimedia Commons.