By guest contributor Pamela C. Nogales C.

Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, Lamartine in front of the Town Hall of Paris rejects the red flag on 25 February 1848

Prompted by the experience of the second world war, historian Lewis Namier described the undemocratic birth of modern republics in his 1848: The Revolution of the Intellectuals (1944) and warned of the unintended consequences of nineteenth-century liberal ideals. On the process of nation-making, he wrote, “States are not created or destroyed, and frontiers redrawn or obliterated, by argument and majority votes;” rather, “nations are freed, united, or broken by blood and iron, and not by a generous application of liberty and tomato-sauce; violence is the instrument of national movements.” He reminded historians that forging national democracies had required men of influence and wealth, who were capable of combining their force to create a government and to defend it against imperial bayonets. Thus, if successful, the government of a democratic nation was composed of those who were victorious in seizing the political leadership of a new state and using its executive force to fight hostile forces—both from outside and within. While their final aim was a world without war, European liberals of the nineteenth century imagined that this end required a national government ready and willing to defend itself against armed invasion and domestic insurrection. It was common, for example, for liberal papers in Prussia to call for war against the Russian Empire in order to secure the success of democratic republics. Thus, already by 1848, the contest for democracy was bound up with the problem of executive force and raised difficult questions about the appropriate means to an end.

Liberals’ strategic orientation toward state governments corresponded to the political realities of 1848. The Austrian, Prussian and Russian Empires, the pillars of the old eighteenth-century “Holy Alliance,” aimed to extinguish any spark of national revolution. And in the end, they were successful—this time, with the help of the soon-to-be French emperor, Louis Bonaparte. In the German states, the Frankfurt National Assembly was dissolved, and revolutionary governments and rebellions were crushed by Prussian troops; Bonaparte dismantled the French National Assembly in Paris, reestablished the monarchy and helped to restore Papal rule in the Italian peninsula; and the republican Magyar government in Hungary was toppled by a joint army of Russian and Austrian forces. This international defeat was among the most formative, political experiences of an entire generation of reformers and it signaled a split in the liberal tradition in Europe and beyond. Political demarcations shifted and became considerably more pronounced after the failure of the revolutions. The republicans, socialists and anarchists of this generation drew different lessons from these conflicts. But at the center of their disputes was the role of the nation in creating a democratic society.

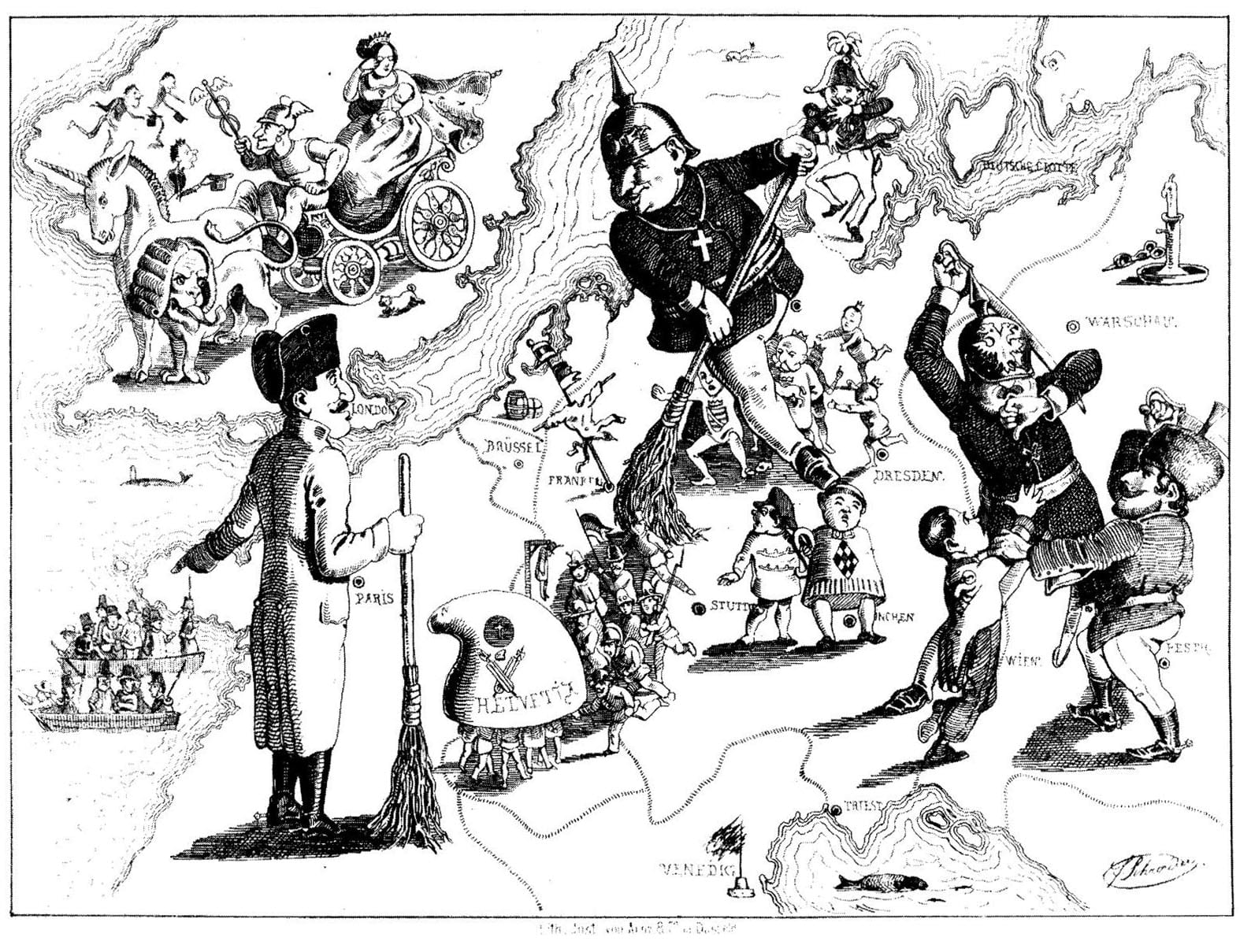

Ferdinand Schröder’s caricature of the suppression of the revolutions of 1848 (published in the Düsseldorfer Monatshefte, August 1849)

While the initial American response to the 1848 revolutions was overwhelmingly positive, the excitement over the French revolution was short-lived in the American capital. The Polk administration sustained the recognition of the new French republic by the U.S. Minister in Paris, Richard Rush, but several government officials preferred a mere congratulatory message—if any. South Carolina’s John Calhoun suggested that the Senate withhold their esteem until a new French Constitution was drafted and a permanent government was installed. Only then would it be possible to know if the national government deserved the Senate’s approbation. A cautious attitude was required because, as Whig Congressman Samuel Phelps of Vermont noted, “when the wheel of revolution begins to revolve, who can…tell where it will stop.”

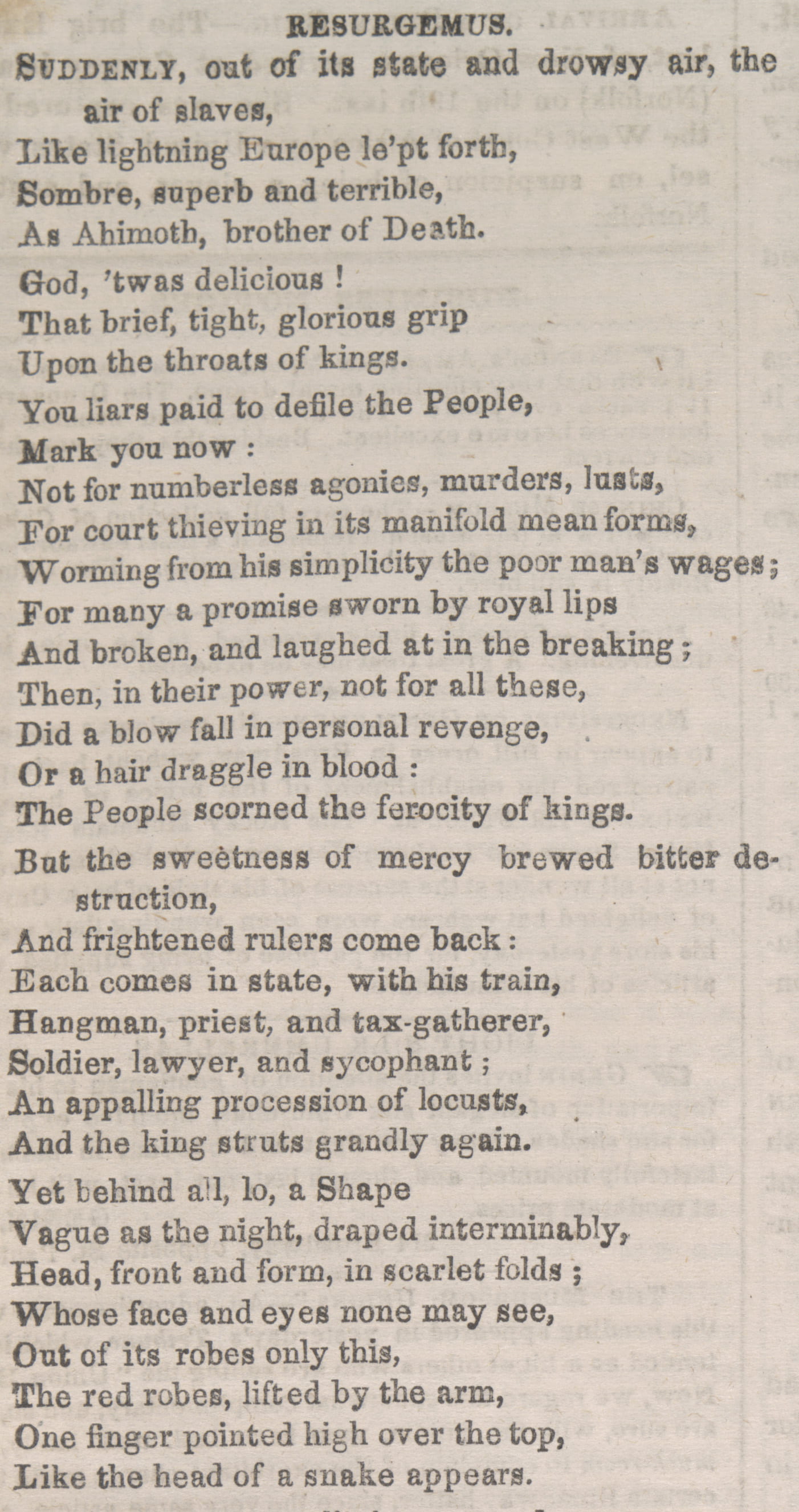

Walt Whitman’s poem “Resurgemus,” paying tribute to the Revolutions of 1848 (published in the New York Daily Tribune, June 21, 1850).

While Calhoun prioritized the stability of the American republic above the risky upheavals of the Parisian workers, abolitionist Fredrick Douglass argued that to abandon the people of France because they demand freedom, jobs and better wages, amounted to a betrayal of America’s revolutionary roots. But Calhoun’s perspective was more representative of the majority of the Senate than those held by the radical abolitionists.

Ambivalence toward the European socialists was common among the liberals in the United States. Of special concern were the French National Workshops, a state program designed to facilitate the employment of all laborers. Whig Senator Daniel Webster commented on the new constitution, which guaranteed “to all Frenchmen, not only liberty and security, but also employment and property.” For Webster this was an impossible task, “How can any government fulfill such a promise?”

The New Orleans Daily Picayune wondered why the French would riot after they were given the vote. Why rebel against their own constituent assembly? Charles A. Dana, a Boston novelist and European correspondent for the New-York Tribune, offered a radical interpretation. He explained that the Revolution of 1789 aimed to destroy feudalism, while the new revolution was “to destroy the moneyed feudalism and lay the foundations of social liberty.” New England poet James Russell Lowell shared Dana’s interpretation when he called 1848 the first social revolution of the modern world. Lowell wrote that the “first French Revolution was only the natural recoil of an oppressed and imbruted people.” In contrast, “the Revolution of 1848 [was] achieved by the working class,” and “at the bottom of [it] lies the idea of . . . social reorganization and regeneration”.Faced with armed citizens in the streets of Paris, the French liberals were forced to confront the “social question” squarely.

The forceful confrontation with the social question was provoked from outside liberal circles. Outside of France, European liberals were supporters of constitutional monarchies, that is, they were the defenders of parliamentary sovereignty over the dynastic power of kings. But they displayed outright contempt for the uneducated masses and had no intention of giving working people the vote. During the revolutions of 1848, it was those who fell under the label “social democrats” who were alone in demanding the extension of the franchise beyond the propertied classes. Among them was a motley crew of utopian socialists, Christian communists and “red Republicans” who rejected an elite democracy for a greater vision of political participation. These radicals were also in conversation with anarchists of different stripes, as well as women like George Sand, the revolutionary French socialist, who included women’s emancipation as part of her utopic demands. These radicals targeted the problems posed by the “hungry ’30s,” the rampant famine in the countryside, the rise in unemployment among city laborers and the decline of the artisan system of production. They argued that contemporary social inequality was hardly a natural outcome of talent, rather, it was a problem of society and thus could be resolved if made subject to politics. The disparate political tendencies grouped under social democracy were thus connected by the belief that the democratic revolutions of previous centuries promised a vision for human emancipation yet to be realized, but one that was receding from view amidst the changing social relations of the nineteenth century. While trying to recover past promises, radicals began to demand a future otherwise unimaginable from the perspective of European liberals alone.

What is the role of the modern nation in the long battle to achieve democracy? This was the question posed in 1848. Liberals, anarchists, and socialists all attempted to answer this question in thought and political practice. Their ideological differences did not correspond to sociological demarcations—they did not “express” a class position. Rather, the differences between these traditions must be found in their intellectual histories as well as their political practice. And we can hardly understand the meaning of these differences without a grasp of the shared concerns across these traditions.

Thibault, “Barricades After the Attack, Rue Saint-Maur” (June 26 1848)

It has become commonplace over the course of the twentieth century to imagine the political traditions of anarchism and socialism as fundamentally opposed to classical liberal values. From this perspective however, it is impossible to understand why an insurrectionary anarchist like Louis-Auguste Blanqui spoke of the French liberal Benjamin Constant as “one of the firmest upholders of French freedom”; why Karl Marx felt indebted to Adam Smith and John Locke for their conception of civil society; why during 1848 and ’49, the red flag was carried sometimes in opposition to but sometimes as a supplement to the tricolor of French republicans; or why the radical tailors of the 1840s reading Gracchus Babeuf out loud in their Parisian workshops still supported small-property ownership as a fundamental right of all free citizens. What we miss by setting up a strict antinomy between these political traditions are their embedded intellectual histories and their entanglement in the revolutionary history of the nineteenth century. We overlook how these ideas were tested, reconfigured and revised in response to the on-going attempts to transform society. And we do a disservice to intellectual history by treating political ideas as static concepts (as hardened “ideology”), rather than deriving their hermeneutic force from the transformative potential they carried at the time of their articulation.

Pamela C. Nogales C. is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at New York University, working on radical political thought on both sides of the Atlantic, with a special interest in the mid-nineteenth century crisis of democracy, the social question, and the contributions by nineteenth-century European political exiles in the United States. She is currently working on her dissertation, “Reform in the Age of Capital: The Transatlantic Roots of Radical Political Thought in the United States, 1828–1877.” She is based in Berlin and can be reached at pam.nogales@gmail.com

July 23, 2018 at 12:08 pm

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.