By guest contributor João Paulo Pimenta

This post is a companion piece to Prof. Pimenta’s article in the Journal of the History of Ideas vol. 79, no. 1, “History of Concepts and the Historiography of the Independence of Brazil: A Preliminary Diagnosis.“

Unique themes emerge and recur within every country’s history for a number of reasons: they relate to subjects that have received significant scholarly attention, they deal with facts that have long-term effects in the life of a country, and they resonate with the general public beyond academia, provoking interest, opinions, and emotional responses. Consider, for example, Independence and the Civil War in the US, Revolution and World War II in France, the Roman Empire in Italy, the Ming Dynasty and the Great Revolution in China, and Immigration and the Malvinas War in Argentina. In Brazil, one might mention the slavery of African populations, the civil and military dictatorship of the late twentieth century, and surely the history of the separation of Brazil from Portugal in the early nineteenth century, which resulted in the creation of a new sovereign state and a new nation, both of them still prevailing.

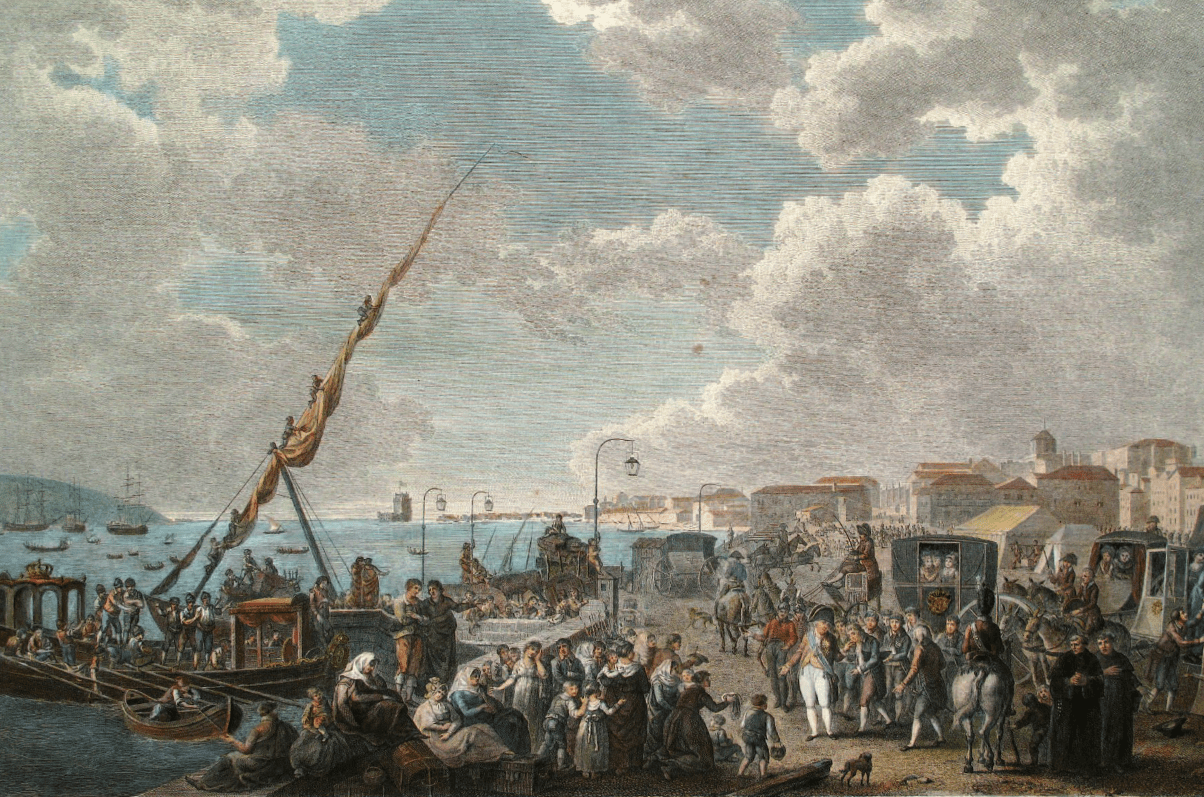

Throughout the Western world, the first years of the nineteenth century are special: relevant events abound, each one seeming to “pull” another toward a more integrated world, producing new conditions that accelerate the process of dramatic, affecting, and sometimes hopeful historical transformation. The changes during the early nineteenth century were profound and enduring, and often political. Brazil, then part of the Portuguese Empire, transformed during this time. While the wars between Napoleonic France and other European powers spread throughout most of the European continent, a particularly pivotal event took place in Portugal: to avoid confronting the enemy, the Portuguese court abruptly chose to leave Lisbon and, under protection of the British Navy, flee to Brazil. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, a contradictory movement started to develop.

The departure of the Portuguese royal family for Brazil, as depicted by Henri L’Evêque

With its new headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, the Portuguese Empire avoided the risk of fragmentation, which was extinguing the Spanish Empire, and escaped French domination. While the empire secured its survival during chaotic wartime Europe, the relocation wrought profound changes and consequences. Rivalries between Portuguese people in Brazil and Portugal, conflicts of interest, and new political expectations prompted a new idea: the assembly of a government and a state in Brazil, separate from Portugal. With Brazilian Independence in 1822, this idea became reality. Now, thanks to this process, there is a country named Brazil, with its own political, economic, military, administrative, juridical, and electoral institutions—its own 210 million citizens.

The declaration of Brazilian independence, as depicted by Pedro Américo

Myriad works have already been written on this subject. And still, it compels the minds and imaginations of professional historians and social scientists, amateur researchers, and laypeople. My article in the January 2018 issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas discusses one of the historiographic renovations that contributes to the ongoing significance of Independence as a theme integral to Brazilian history. “Conceptual history” or “Begriffsgeschichte”— which attends to the words, languages, and political ideas that made history—is not a new approach. But when applied to Brazilian Independence, the history of concepts casts new light on overlooked elements of the event, and reveals its significance not only to Brazilian history, but also to our shared global history.

João Paulo Pimenta holds a Ph.D. in History from the Universidade de São Paulo, where he has been a professor in the History Department since 2004. He has also been a visiting professor at El Colégio de México (2008, 2016, 2017), at the Universitat Jaume I, Spain (2010), at the Pontifícia Universidad Católica de Chile (2013), at the Universidad de

la República, Uruguay (2015) and at the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador (2015, 2016). His work explores the history of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, especially the relationship between Brazil and Hispanic America; the national question and collective identities; and the history of historical times in Brazil and the wider Western World.

1 Pingback