By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich

Antonio Rodríguez, Saint Augustine

In his magisterial history of the Reformation, Diarmaid MacCulloch wrote, “from one perspective, a century or more of turmoil in the Western Church from 1517 was a debate in the mind of long-dead Augustine.” MacCulloch riffs on B. B. Warfield’s pronouncement that “[t]he Reformation, inwardly considered, was just the ultimate triumph of Augustine’s doctrine of grace over Augustine’s doctrine of the Church” (111). There can be no denying the centrality to the Reformation of Thagaste’s most famous son. But Warfield’s “triumph” is only half the story—forgivably so, from the last of the great Princeton theologians. Catholics, too, laid claim to Augustine’s mantle. Not least among them was a Toledan Jesuit by the name of Pedro de Ribadeneyra, whose particular brand of personal Augustinianism offers a useful tonic to the theological and polemical Augustine.

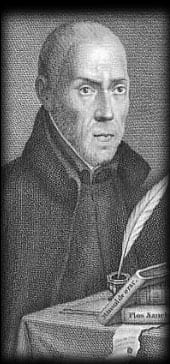

Pedro de Ribadeneyra

To quote Eusebio Rey, “I do not believe there were many religious writers of the Siglo de Oro who internalized certain ascetical aspects of Saint Augustine to a greater degree than Ribadeneyra” (xciii). Ribadeneyra translated the Confessions, the Soliloquies, and the Enchiridion, as well as the pseudo-Augustinian Meditations. His own works of history, biography, theology, and political theory are filled with citations, quotations, and allusions to the saint’s oeuvre, including such recondite texts as the Contra Cresconium and the Answer to an Enemy of the Laws and the Prophets. In short, like so many of his contemporaries, Ribadeneyra invoked Augustine as a commanding authority on doctrinal and philosophical issues. But there is another component to Ribadeneyra’s Augustinianism: his spiritual memoir, the Confesiones.

Composed just before his death in September 1611, Ribadeneyra’s Confesiones may be the first memoir to borrow Augustine’s title directly (Pabel 456). Yet, a title does not a book make. How Augustinian are the Confesiones?

Pierre Courcelle, the great scholar of the afterlives of Augustine’s Confessions, declared that “the Confesiones of the Jesuit Ribadeneyra seem to have taken nothing from Augustine save the form of a prayer of praise” (379). Of this commonality there can be no doubt: Ribadeneyra effuses with gratitude to a degree that rivals Augustine. “These mercies I especially acknowledge from your blessed hand, and I praise and glorify you, and implore all the courtiers of heaven that they praise and forever thank you for them” (21). Like the Confessions, the Confesiones are written as “an on-going conversation with God to which […] readers were deliberately made a party” (Pabel 462). That said, reading the two side-by-side reveals deeper connections, as the Jesuit borrows from Augustine’s life story in narrating his own.

Though Ribadeneyra could not recount flirtations with Manicheanism or astrology, he could follow Augustine in subjecting his childhood to unsparing critique. His early years furnished—whose do not?—sufficient petty rebellions to merit Augustinian laments for “the passions and awfulness of my wayward nature” (5–6). In one such incident, Pedro stubbornly demands milk as a snack; enraged by his mother’s refusal, he runs from the house and begins roughhousing with his friends, resulting in a broken leg. Sin inspired by a desire for dairy sets up an echo of Augustine’s rebuke of

the jealousy of a small child: he could not even speak, yet he glared with livid fury at his fellow-nursling. […] Is this to be regarded as innocence, this refusal to tolerate a rival for a richly abundant fountain of milk, at a time when the other child stands in greatest need of it and depends for its very life on this food alone? (I.7,11)

Luis Tristán, Santa Monica

Ribadeneyra’s mother, Catalina de Villalobos, unsurprisingly plays the role of Monica, the guarantor of his Catholic future (while pregnant, Catalina vows that her son will become a cleric). She was not the only premodern woman to be thus canonized by her son: Jean Gerson tells us that his mother, Élisabeth de la Charenière, was “another Monica” (400n10).

Leaving Toledo, Pedro comes to Rome, which was cast as one of Augustine’s perilous earthly cities. Hilmar Pabel points out that the Jesuit’s description of the city as “Babylonia” imitates Augustine’s jeremiad against Thagaste as “Babylon” (474). Like its North African predecessor, this Italian Babylon threatens the soul of its young visitor. Foremost among these perils are teachers: in terms practically borrowed from the Confessions, Ribadeneyra decries “those who ought to be masters, [who] are seated in the throne of pestilence and teach a pestilent doctrine, and not only do not punish the evil they see in their vassals and followers, but instead favor and encourage them by their authority” (7–8).

After Ribadeneyra left for Italy, Catalina’s duties as Monica passed to Ignatius of Loyola, who combined them with those of Ambrose of Milan—the father-figure and guide encountered far from home . Like Ambrose, Ignatius acts como padre, one whose piety is the standard that can never be met, who combines affection with correction.

A young Ignatius of Loyola

The narrative climax of the Confessions is Augustine’s tortured struggle culminating in his embrace of Christianity. No such conversion could be forthcoming for Ribadeneyra, its place taken by tentacion, an umbrella term encapsulating emotional upheavals, doubts over his vocation, the fantasy of returning to Spain, and resentment of Ignatius. Famously, Augustine agonizes until he hears a voice that seems to instruct him, tolle lege (VIII.29). Ribadeneyra structures the resolution of his own crises in analogous fashion, his anxieties dissolved by a single utterance of Ignatius’s: “I beg of you, Pedro, do not be ungrateful to one who has shown you so many kindnesses, as God our Lord.” “These words,” Ribadeneyra tells us, “were as powerful as if an angel come from heaven had spoken them,” his tentacion forever banished (37).

I am not suggesting Ribadeneyra fabricated these incidents in order to claim an Augustinian mantle. But the choices of what to include and how to narrate his Confesiones were shaped, consciously and unconsciously, by Augustine’s example.

Ribadeneyra’s story also diverges from its Late Antique model, and at times the contrast is such as to favor the Jesuit, however implicitly. Ribadeneyra professes an unmistakably early modern Marian piety that has no equivalent in Augustine. Where Monica is reassured by a vision of “a young man of radiant aspect” (III.11,19), Catalina de Villalobos makes her vow to vuestra sanctíssima Madre y Señora nuestra (3). Augustine addresses his gratitude to “my God, my God and my Lord” (I.2, 2), while Ribadeneyra, who mentions his travels to Marian shrines like Loreto, is more likely to add the Virgin to his exclamations: “and in particular I implored your most glorious virgin-mother, my exquisite lady, the Virgin Mary” (11). The Confessions mention Mary only twice, solely as the conduit for the Incarnation (IV.12, 19; V.10, 20). Furthermore, Ribadeneyra’s early conquest of his tentaciones produces a much smoother path than Augustine’s erratic embrace of Christianity; thus the Jesuit declares, “I never had any inclination for a way of life other than that I have” (6). His rhapsodic praise of chastity—“when could I praise you enough for having bound me with a vow to flee the filthiness of the flesh and to consecrate my body and soul to you in a clean and sweet sacrifice” (46)—is far cry from the infamous “Make me chaste, Lord, but not yet” (VIII.17)

When Ribadeneyra translated Augustine’s Confessions into Spanish in 1596, his paratexts lauded Augustine as the luz de la Iglesia and God’s signal gift to the Church. There is no hint—anything else would have been highly inappropriate—of equating himself with Augustine, whose ingenio was “either the greatest or one of the greatest and most excellent there has ever been in the world.” As a last word, however, Ribadeneyra mentions the previous Spanish version, published in 1554 by Sebastián Toscano. Toscano was not a native speaker, “and art can never equal nature, and so his style could not match the dignity and elegance of our language.” It falls to Ribadeneyra, in other words, to provide the Hispanophone world with the proper text of the Confessions; without ever saying so, he positions himself as a privileged interpreter of Augustine.

The Confessions is a profoundly personal text, perhaps the seminal expression of Christian subjectivity—told in a searingly intense first-person. Ribadeneyra himself writes that in the Confessions “is depicted, as in a masterful portrait painted from life, the heavenly spirit of Saint Augustine, in all its colors and shades.” Without wandering into the trackless wastes of psychohistory, it must have been a heady experience for so devoted a reader of Augustine to compose—all translation being composition—the life and thought of the great bishop.

Ribadeneyra was of course one of many Augustinians in early modern Europe, part of an ongoing Catholic effort to reclaim the Doctor from the Protestants, but we will misunderstand his dedication if we regard the saint as no more than a prime piece of symbolic real estate. For scholars of early modern Augustinianism have rooted the Church Father in philosophical schools and the cut-and-thrust of confessional conflict. To MacCulloch and Warfield we might add Meredith J. Gill, Alister McGrath, Arnoud Visser, and William J. Bouwsma, for whom early modern thought was fundamentally shaped by the tidal pulls of two edifices, Augustinianism and Stoicism.

There can be no doubt that Ribadeneyra was convinced of Augustine’s unimpeachable Catholicism and opposition to heresy—categories he had no hesitation in mapping onto Reformation-era confessions. Equally, Augustine profoundly influenced his own theology. But beyond and beneath these affinities lay a personal bond. Augustine, who bared his soul to a degree unmatched among the Fathers, was an inspiration, in the most immediate sense, to early modern believers. Like Ignatius, the bishop of Hippo offered Ribadeneyra a model for living.

That early modern individuals took inspiration from classical, biblical, and late antique forebears is nothing new. Bruce Gordon writes that, influenced by humanist notions of emulation, “through intensive study, prayer and conduct [John] Calvin sought to become Paul” (110). Mutatis mutandis, the sentiment applies to Ribadeneyra and Augustine. Curiously, Stephen Greenblatt’s seminal Renaissance Self-Fashioning does not much engage with emulation, concerning itself with self-fashioning as creation ad nihilum—that is to say, a new self, not geared toward an existing model (Greenblatt notes in passing, and in contrast, the tradition of imitatio Christi). Ribadeneyra, in reading, translating, interpreting, citing, and imitating Augustine, was fashioning a self after another’s image. As his Catholicized Confesiones indicate, this was not a slavish and literal-minded adherence to each detail. He recognized the great gap of time that separated him from his hero, changes that demanded creativity and alteration in the fashioning of a self. This need not be a thought-out or even conscious plan, but simply the cumulative effect of a lifetime of admiration and inspiration. Without denying Ribadeneyra’s formidable mind or his fervent Catholicism, there is something to be gained from taking emotional significance as our starting point, from which to understand all the intellectual and personal work the Jesuit, and others of his time, could accomplish through a hero.

1 Pingback